The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has moved a step closer to a radical solution for controlling Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. In a preliminary finding (pdf) published on Friday (Mar. 11), the FDA said that the use of genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes as a pest-control method in a controlled trial—as proposed by the UK company Oxitec—will have “no significant impact” on human health or the environment.

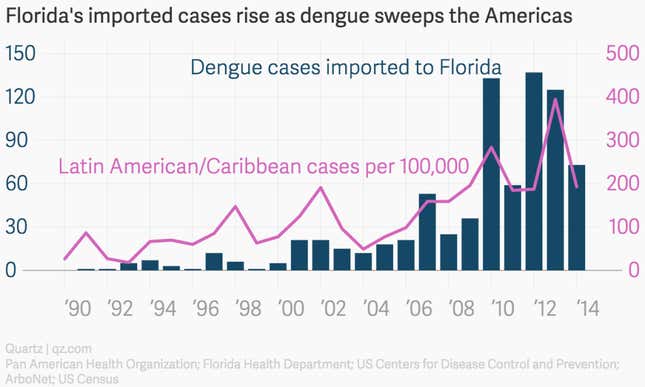

As Quartz reported last year, Florida’s dengue outbreaks had already given the FDA enough reason to approve the trial. Now, with the Zika virus threat increasing as summer approaches, there are more reasons.

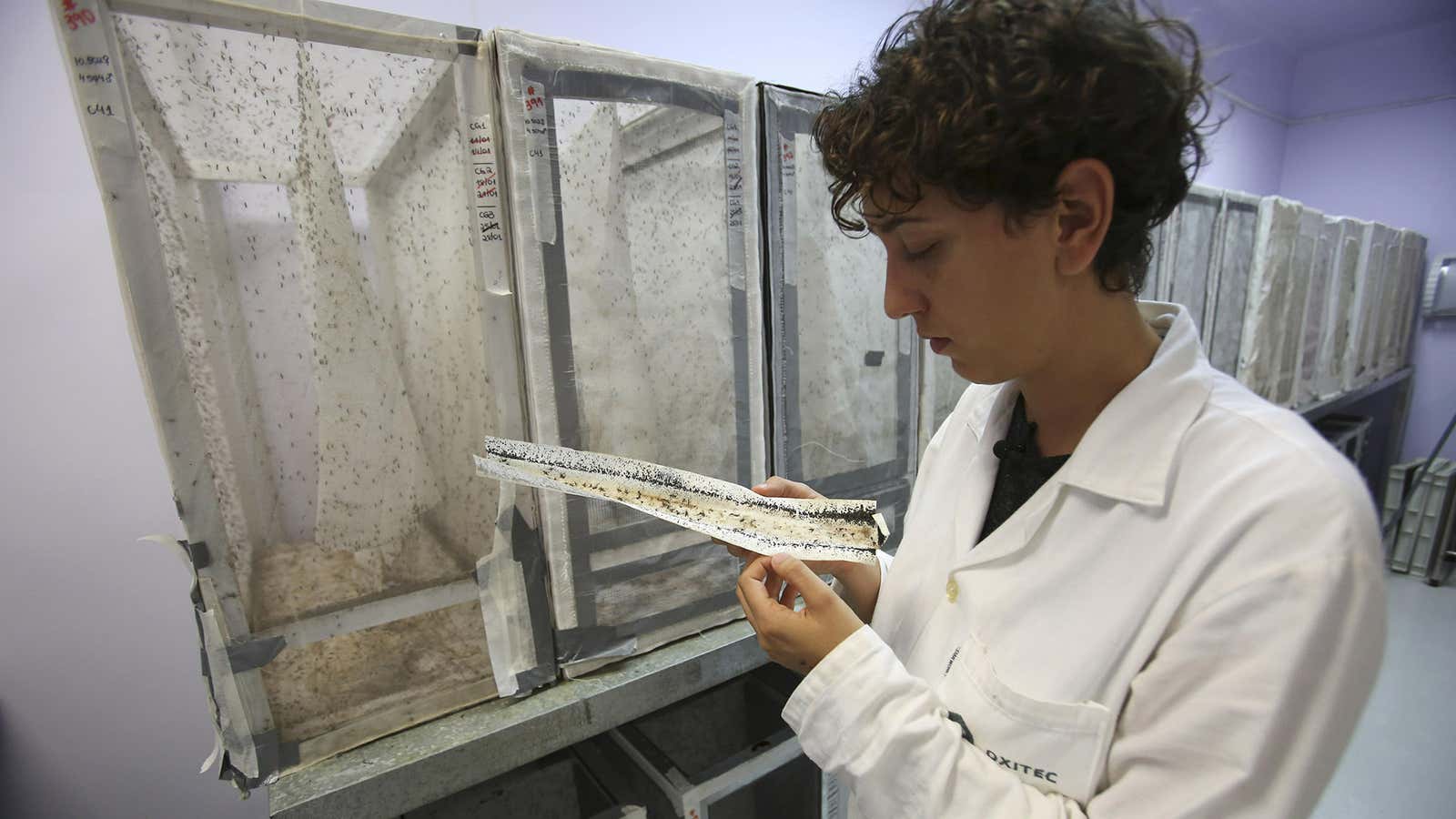

These GM mosquitoes, made by Oxitec, have already been trialled in the Cayman Islands, Malaysia, Panama, and Brazil. In each of those trials, Oxitec claims, its GM mosquitoes reduced the local A. aegypti population by more than 90%. Following early success, in January the mayor of Piracicaba, where the Brazilian trial was conducted and which is facing an outbreak of the Zika virus, agreed to expand the use of Oxitec’s mosquitoes.

Oxitec says it has learned to, in essence, tweak mosquitoes to kill their own kind. Using genes from an assortment of organisms—E. coli, the herpes virus, and cabbage, to name a few—it has modified A. aegypti to produce a protein which will kill off its offspring. That is, unless the offspring are fed tetracycline, which is how Oxitec grows the larvae to adulthood. When Oxitec’s male mosquitoes mate with a wild female, without access to tetracycline, the offspring die before reaching adulthood.

Experts are supportive of the FDA’s decision. David O’Brochta of the University of Maryland said he is “not surprised” by FDA’s decision. Bruce Hay of the California Institute of Technology said Oxitec’s mosquitoes cannot do “anything other than what they are intended to do.” Jason Rasgon of Pennsylvania State University said Oxitec’s GM strategy is “by far the safest and the least likely to have off target effects.”

Still, let’s address some of the concerns. Oxitec’s killing machine is not perfect, and it is important to address any unintended consequences.

First, Oxitec says that about 95% of all offspring die. That means some 5% of offspring would live to carry the modified gene. Would that lead to spreading of the modified gene? No, because the gene is self-limiting. With every new generation of mosquitoes born, the presence of those with the modified gene will fall drastically. Here’s a simple calculation if 500,000 GM mosquitoes are released today.

Second, although Oxitec manually separates male from female larvae, it’s not perfect. That means some of the GM mosquitoes released (less than one in 1,000) will be a female, which matters because it is only female mosquitoes that bite humans. Would those bites carry the artificial protein the GM mosquitoes are producing? No, Oxitec says, because the female mosquitoes have no detectable level of the artificial protein.

The FDA has released Oxitec’s environmental assessment (pdf) for the proposed trial, which addresses other minor concerns. If you still don’t like the idea, you have 30 days to get FDA’s attention.

In the short-term, it seems like the FDA is right to at least try out GM mosquitoes. Once their use is stopped, Oxitec said, the A. aegypti population will spring back to normal levels. So, in the long-term, it’s unlikely that releasing expensive batches of GM mosquitoes every so often is an economically viable solution.

A. aegypti is the cockroach of mosquitoes and it is highly adapted to living in urban habitats. Fortunately, there is a weapon in preparation that could completely eliminate a mosquito species’ ability to carry disease-causing pathogen.