Abstract

Carnivore and humans live in proximity due to carnivore recovery efforts and ongoing human encroachment into carnivore habitats globally. The American West is a region that uniquely exemplifies these human-carnivore dynamics, however, it is unclear how the research community here integrates social and ecological factors to examine human-carnivore relations. Therefore, strategies promoting human-carnivore coexistence are urgently needed. We conducted a systematic review on human-carnivore relations in the American West covering studies between 2000 and 2018. We first characterized human-carnivore relations across states of the American West. Second, we analyzed similarities and dissimilarities across states in terms of coexistence, tolerance, number of ecosystem services and conflicts mentioned in literature. Third, we used Bayesian modeling to quantify the effect of social and ecological factors influencing the scientific interest on coexistence, tolerance, ecosystem services and conflicts. Results revealed some underlying biases in human-carnivore relations research. Colorado and Montana were the states where the highest proportion of studies were conducted with bears and wolves the most studied species. Non-lethal management was the most common strategy to mitigate conflicts. Overall, conflicts with carnivores were much more frequently mentioned than benefits. We found similarities among Arizona, California, Utah, and New Mexico according to how coexistence, tolerance, services and conflicts are addressed in literature. We identified percentage of federal/private land, carnivore family, social actors, and management actions, as factors explaining how coexistence, tolerance, conflicts and services are addressed in literature. We provide a roadmap to foster tolerance towards carnivores and successful coexistence strategies in the American West based on four main domains, (1) the dual role of carnivores as providers of both beneficial and detrimental contributions to people, (2) social-ecological factors underpinning the provision of beneficial and detrimental contributions, (3) the inclusion of diverse actors, and (4) cross-state collaborative management.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

Introduction

Carnivore and human populations are often in proximity to each other, due to carnivore recovery efforts in some areas (e.g. North America, Europe) and ongoing human encroachment into carnivore habitats globally. Increasing proximity prompts more frequent interactions between carnivores and humans. These interactions are often viewed through the lens of 'conflict' or 'risk' to human communities, such as livestock depredation, impacts on abundances of game species, and threats to human safety (e.g. Treves and Karanth 2003, Treves et al 2004, Inskip and Zimmermann 2009, Dickman 2010, Miller 2015, van Eeden et al 2018, Lozano et al 2019). However, carnivores can also benefit humans by the provision of ecosystem services such as the mitigation of diseases (Harris and Dunn 2010), carcass removal (Moleón et al 2014, O'Bryan et al 2018) and opportunities provided for ecotourism (Willemen et al 2015, Arbieu et al 2017). Carnivores and humans are therefore considered parts of integrated social-ecological systems, whereby the mutual wellbeing is inextricably linked (Carter et al 2014, Darimont et al 2018, Dressel et al 2018, Lischka et al 2018, Lozano et al 2019).

The American West is an evocative and unique region that exemplifies dynamic human-carnivore relations (e.g. Kellert et al 1996, Young et al 2015, Bruskotter et al 2017, Slagle et al 2017, Jones et al 2019). In this region there are areas with intact carnivore guilds and wilderness; yet rapid human development and polarizing debate about carnivore management threaten the future of these animals and can hinder effective policy-making (Bangs and Shivik 2001, Linnell et al 2001, Bruskotter 2013, Bradley et al 2015, Smith et al 2016). In particular, interaction between livestock and carnivores generates intense controversy in the American West (van Eeden et al 2018), where publically-owned grazing land is ubiquitous and livestock production is an important economic sector (Sarchet 2005). Legal hunting has also generated intense debate among actors about the ways to solve human-carnivore conflicts and conserve carnivores (Treves and Naughton-Treves 2005, Treves 2009). Strategies that promote coexistence between humans and carnivores in multi-use landscapes are therefore urgently needed in order to balance the goals of nature preservation and livelihood protection in the American West.

Using the definition by Carter and Linnell (2016), we characterize coexistence as the 'dynamic but sustainable state in which humans and carnivores co-adapt to living in shared landscapes where human relations with carnivores are governed by effective institutions that ensure long-term carnivore population persistence, social legitimacy, and tolerable levels of risk and damage.' Then, we use coexistence as an umbrella concept that encompasses 'tolerance', which could be defined (based on Bruskotter and Wilson 2014) as the 'human acceptance' of the risks and damages caused by carnivores, a necessary condition to achieve a permanent coexistence (Carter and Linnell 2016).

Given these definitions, many ecological and social factors, heterogeneous in both space and time, can facilitate or limit human-carnivore coexistence (Frank et al 2019). Among the ecological factors, the species involved (Kansky et al 2014) and the ecosystems that they inhabit, are likely relevant in determining coexistence. Also, several social factors might foster or constrain coexistence, such as the type of actors involved, gender, or education level (e.g. Morzillo et al 2007, 2010, Agarwala et al 2010, Smith et al 2014, Lute et al 2016), as well as the attributes of the governance systems (Borrini-Feyerabend and Hill 2015). However, it is unclear the extent to which the research community integrates social and ecological factors to examine human-carnivore coexistence in the American West. Furthermore, studies tend to emphasize conflicts with carnivores and rarely assess the variety of services they provide to people (Lozano et al 2019). Yet, acknowledging and understanding the multiple ecosystem services (i.e. benefits) and disservices (i.e. risks and damages) carnivores provide to people allow for a more comprehensive, and defensible, evaluation of the trade-offs of coexisting with these species (e.g. Ripple et al 2014, Braczkowski et al 2018, Morales-Reyes et al 2018). Finally, recent research suggests the need of reconnecting people with nature (Folke et al 2011, Ives et al 2017). The concept of human-nature connectedness integrates different relationships between social and natural systems (Ives et al 2017, 2018). In this context, experiential (e.g. recreational activities in nature), emotional (e.g. affective response to nature), and cognitive (e.g. knowledge, beliefs and attitudes) connections are important for human well-being and play a useful role in fostering conservation and tolerance of carnivores. Therefore, identifying and clarifying knowledge gaps in coexistence research in the American West can shed light on where the field has been, where it stands, and where it might go in the future.

Here, we conducted a systematic review of the literature on human-carnivore relations in the American West published between 2000 and 2018. To do so, we first characterized human-carnivore relations across states of the American West according to ecological (e.g. species, biomes) and social factors (e.g. actors and management). Second, we analyzed the similarities and dissimilarities across states of the American West in terms of coexistence and tolerance (mentioned or evaluated in the reviewed literature), the number of ecosystem services and conflicts mentioned. Third, we quantified the effect of social and ecological factors that influence the mention of coexistence, tolerance, ecosystem services and conflicts in the scientific literature across states of the American West. Through this analysis, we reveal the underlying biases in human-carnivore relations research in the American West and outline a road map for advancing the theory and practice of human-carnivore coexistence in this important region.

Methods

We searched for articles indexed by the Scopus database following guidelines of Pullin and Stewart (2006). We based the search on the systematic review conducted by Lozano et al (2019) and their final 2000–2016 database1. We used the same search query to include articles published until 2018 and only carried out in the American West. The search string included four main elements: (1) human-carnivore relations, (2) ecosystem services, (3) conflicts and (4) the taxonomic groups of terrestrial carnivores (see appendix A for the full search string). We used different terms referring to conflicts (i.e. 'conflict*' OR 'damage*' OR 'impair*' OR 'harm*'), ecosystem services (i.e. 'ecosystem service*' OR 'ecosystem good*' OR 'environmental service*') and human-carnivore relations (i.e. 'human-wildlife' OR 'human-carnivore*' OR 'human-felid*' OR 'human-canid*'), since these can represent negative, positive or neutral relations with carnivores, respectively. The search was applied to the fields title, abstract and keywords (see Lozano et al 2019), and the final number of selected articles for in-depth review was 71 (see appendix B for detailed methods of the review process).

For all the articles reviewed (see appendix C), we registered the ecological and social factors considered. Regarding ecological variables, we included: (1) biome type (based on MA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment) 2005), (2) carnivore family and (3) carnivore species. Regarding social factors, we considered (1) type of social actor (based on Lozano et al 2019), and (2) type of management action (according to Inskip and Zimmerman (2009) and Lozano et al 2019). We also coded different variables representing human-carnivore relations: (1) whether human-carnivore 'coexistence' was mentioned (based on Carter and Linnell 2016), (2) whether 'tolerance' or 'acceptance' of carnivores were mentioned or evaluated in the article (based on Gore et al 2006, Bruskotter and Wilson 2014 and Kansky et al 2014), (3) type of ecosystem services mentioned (based on MA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment) 2005) and (4) type of human-carnivore conflict considered (based on Peterson et al 2010 and Lozano et al 2019). For a detailed description of the variables included, see appendix D.

Firstly, we performed a descriptive analysis to present the state of knowledge regarding human-carnivore relations research in the American West. Secondly, similarities regarding human-carnivore relations research across states of the American West were analyzed by nonparametric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) using the 'vegan' R package (Oksanen et al 2019). 17 out of 71 articles were conducted simultaneously in several states of the American West. Then, to obtain the different variables across states, the information was disaggregated and assigned to each of the states separately, so information provided by one article can be assigned to different states (N = 120). The states of the American West were arranged on a Cartesian axis based on the terms of coexistence, tolerance toward carnivores (mentioned or evaluated), number of ecosystem services and number of conflicts reported by articles in each state. A shorter distance between states would mean greater similarity in the way scientists approach research on human-carnivore relations. We used the Mahalanobis distance, which takes into account the potential correlation between the variables used in the ordination. In addition, we fitted the number of types of human-nature connection (according to Ives et al 2017) mentioned in articles using penalized splines (Oksanen et al 2019). Two types of human-nature connection were fitted: experiential and emotional; we excluded cognitive connections as this category was not mentioned in the articles considered. We used Kruskal's stress (Kruskal 1964) to check for the goodness of fit of the NMDS. Kruskal's stress measures the agreement in the rank order of the inter-state distances observed and those predicted from the similarities. According to Clarke's (1993) guidelines for stress values, values lower than 0.3 indicate that the arrangement reached is better than one obtained randomly.

Finally, we used a Bayesian modeling approach to quantify the effect of ecological and social variables influencing the number of (1) articles mentioning human-carnivore coexistence, (2) articles mentioning or evaluating tolerance toward carnivores, (3) ecosystem services mentioned, and (4) conflicts reported. All variables were aggregated by states of the American West (see above). We estimated the effect of the following predictor variables: percentage of federal and private land (average of percentage of 2000, 2010 and 2015; obtained from Vincent et al 2017), number of articles according to carnivore family, number of social actors mentioned (i.e. three types included: local, non-local, and manager/academia), number of management actions mentioned (i.e. three types included: non-lethal actions, community development programs, and lethal control interventions), number of ecosystem services mentioned (i.e. two types included: regulating and cultural; we exclude provisioning services because these were only mentioned twice in one article), number of conflicts reported (i.e. four types included: damage to human food, damage to human property, damage to human safety and human–human conflicts; we excluded damage to biodiversity as it was only mentioned in one article). The number of articles across states was also included in the models as a covariate. All the variables were standardized to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of 1. We built spatial models assuming a Besag–York–Mollie specification (Besag et al 1991) using the R-integrated nested Laplace approximation (INLA) package (Rue et al 2009) (see appendix E for details and models parameterization). INLA is a computationally efficient method for fitting Bayesian models while accounting for spatial dependence of residuals (i.e. model residuals at nearby states are not independent) (Blangiardo and Cameletti 2015). Altogether, we built separate models for each of the following response variables: the number of mentions of human-carnivore coexistence, tolerance towards carnivores, ecosystem services, and conflicts (i.e. 56 models in total). Each of the models included one intercept, one predictor variable listed above (a different one each model), the number of articles conducted in each state as a covariate and one spatially structured term. All the analyses were performed using R software version 3.6.0 (R Core Team 2019).

Results

State-of-the-science in human-carnivore relations

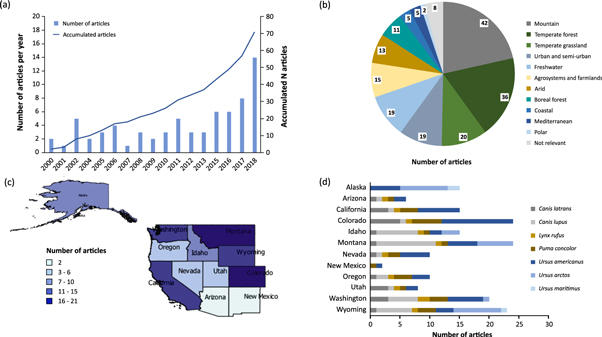

The number of published articles since 2000 concerning human-carnivore relations in the American West has rapidly increased, with a peak in 2018 with 14 articles (figure 1(a)). The largest proportion of research was conducted in Colorado (29.6% of articles), followed by Montana (26.8% of articles), Wyoming (22.5% of articles), and Washington (18.3% of articles), whereas Arizona and New Mexico received relatively less attention (figure 1(b)). Most articles were carried out in mountain areas (59.2%) and temperate forests (50.7%), whereas Mediterranean ecosystems (7.0%) and polar environments (2.8%) were scarcely represented in articles (figure 1(c)).

Figure 1. Distribution of reviewed articles according to (a) time, (b) biome, (c) state, and (d) particular species by state.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFamilies most studied were Ursidae (63.4% of articles) followed by Canidae (wolves and coyotes; 31%) and Felidae (cougars and bobcats; 14.1%). Most articles only included one species (88.7% of articles). The American black bear (Ursus americanus; 39.4% of articles) was the most frequently studied followed by brown bear (U. arctos; 28.2%), grey wolf (Canis lupus; 21.1%), cougar (Puma concolor; 14.1%) and coyotes (C. latrans; 11.3%). Only 2.8% of articles focused on other carnivores such as polar bears (U. maritimus) and bobcats (Lynx rufus). Seven out of 71 articles (9.9%) dealt with reintroduced carnivores (mainly wolves). Interestingly, there was no article focusing on small or medium-sized carnivores. Among the three most studied carnivores, American black bear was most frequently studied in Colorado (22.6%) and California (13.2%), brown bear in Alaska (30.8%) and Wyoming (30.8%) and grey wolf in Montana (28.6%) and Idaho (20%) (figure 1(d)).

Coexistence and tolerance toward carnivores in the American West

Coexistence was mentioned in 25.4% of articles, whereas human tolerance toward carnivores was mentioned or evaluated in 43.7% of articles. Coexistence was more frequently mentioned in articles conducted in Colorado (22.6%) and Montana (19.4%), while tolerance was mainly mentioned or evaluated in Montana (22%), Colorado (15%) and Idaho (13%).

Social actors

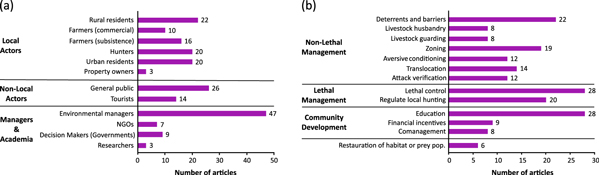

Sixty-four articles (90.1%) mentioned any type of social actor involved in the study of human-carnivore relations. Local actors were the most frequently mentioned social actor type (70.4% of articles), particularly rural (31.0% of articles), urban residents (28.2%) and hunters (28.2%), while subsistence and commercial farmers were mentioned in 22.5% and 14.1% of articles, respectively. Thirty-tree articles (46.5%) mentioned non-local actors, specifically 36.6% of articles referred to general public and 19.7% of articles to tourists. In addition, actors from academia and managers were mentioned in 48 articles out of 71 (67.6%), environmental managers were mentioned in 66.2 % of articles, while decision makers in governments were considered in 12.7% of articles, NGOs/conservationists in 9.9%, and researchers were mentioned less frequently (4.2%) (figure 2(a)).

Figure 2. Number of articles that mentioned (a) types of social actors involved, and (b) management actions implemented for dealing with human-carnivore conflicts.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageHuman-carnivore management actions

Management recommendations towards carnivores were mentioned in 90.1% of articles. Non-lethal measures were the most mentioned management action to alleviate human-carnivore conflicts (66.2% of articles); 31% of articles mentioned the use of deterrents and barriers (e.g. specialized electric fencing, lights and loud noises), 26.8% of articles reported zoning (i.e. separating livestock grazing from carnivores' habitat) as a management action. Translocation was mentioned in 19.7% of articles, and aversive conditioning and verification of attacks were both mentioned in 16.9% of the articles, whilst livestock guarding (11.3%) and husbandry techniques (11.3%) were less frequently mentioned (figure 2(b)).

Management actions that target community development were mentioned in 47.9% of the articles. In particular, 39.4% of articles mentioned actions related to education programs while economic incentives (12.7% of articles) and co-management (11.3% of articles) were less mentioned. Finally, 33 articles out of 71 (46.5%) mentioned lethal management actions, specifically individual removal (39.4% of articles) and hunting permit regulations (28.2% of articles) were reported (figure 2(b)). Despite this, only 20 articles out of 71 (28.2%) tested the effectiveness of different management practices in reducing damages occurrence (i.e. garbage disposal, deterrent and aversive techniques, or effectiveness of education programs).

Ecosystem services and human-carnivore conflicts

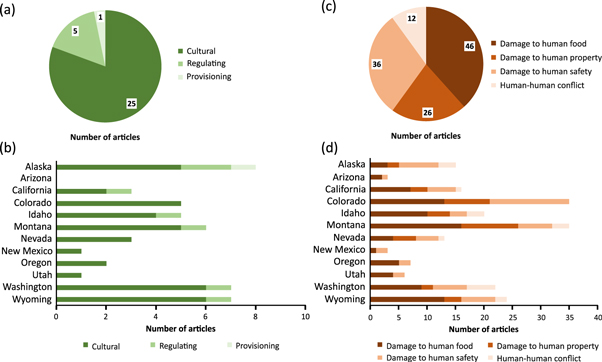

More than half of articles focused only on conflicts (62.0% of articles), followed by articles mentioning both services and conflicts (36.6%). Only 1.4% of articles exclusively mentioned services of carnivores to society. Regarding the ecosystem services provided by carnivores, 35.2% of articles mentioned cultural services, mainly sport hunting (25.4% of articles), while 7% of the articles referred to regulating services, such as important roles of apex predators (5.6% of articles), and 1.4% of articles mentioned provisioning services (i.e. fur and food) (figure 3(a)). Most articles mentioning cultural services were conducted in Wyoming (15%) and Washington (15%). Regulating services were more frequently mentioned in Alaska (28.6%) than in other states, and this state was the only one that mentioned provisioning services. New Mexico (2.5%) and Utah (2.5%) scarcely mentioned any ecosystem services (in both states regulating services were mentioned once) while Arizona did not mention any ecosystem services (figure 3(b)).

Figure 3. Number of articles for human-carnivore relations in the American West that mentioned different (a) types of ecosystem services, (b) types of ecosystem services by state, (c) types of conflicts, and (d) types of conflict by state.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageSeventy out of 71 articles mentioned conflicts, 64.8% of articles mentioned damages to human food resources (mainly predation on livestock and poultry), 50.7% of articles mentioned damage to human safety, 36.6% of articles mentioned damage to human property and human–human conflicts were considered by 16.9% of articles (figure 3(c)). Damage to biodiversity was only mentioned in one article (Ziegltrum and Nolte 2000). Regarding conflicts per state, damage to food were more frequently mentioned in articles carried out in Montana (18.4%), Wyoming (14.9%) and Colorado (14.9%). In addition, damage to human property (e.g. damage to trash containers, or noisy activities) was mainly mentioned in Montana (27.8%) and Colorado (22.2%), damage to human safety was mostly frequently mentioned in Colorado (24.1%), and human–human conflicts were more frequently mentioned in Washington (27.8%) (figure 3(d)).

Measuring similarity across states

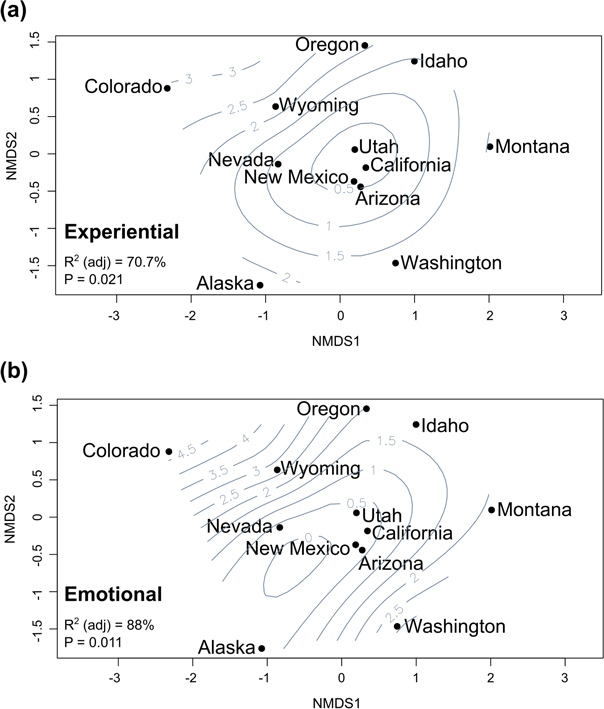

The states of the American West were optimally arranged according to coexistence mentioned, tolerance mentioned or evaluated, number of ecosystem services and conflicts mentioned by articles (Kruskal's stress 0.16 < 0.3). The spatial configuration of the states reached by the NMDS analysis (figure 4) suggests that there are different human-carnivore relations in the American West, with some states sharing the composition of these relations, and others having a more dissimilar one. For example, we found that Arizona, California, Utah, and New Mexico were closely arranged (figure 4), while the rest of the American West states showed a dissimilar composition to any other state, being isolated in ordination space. Alaska and Idaho were the farthest states from each other, and therefore, the most dissimilar. The experiential and emotional human-carnivore connections fitted well to the ordination (figures 4(a) and (b)). Although some states were dissimilar in terms of human-carnivore relations and ecosystem services mentioned, they shared similar composition of mentions of experiential human-carnivore connections (e.g. Alaska, Oregon, and Montana; figure 4(a)). In contrast, states located away from each other also had a dissimilar composition of mentions of emotional connections (e.g. Alaska, Colorado and Oregon; figure 4(b)).

Figure 4. Nonparametric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) using Mahalanobis dissimilarity. The axes NMDS1 and NMDS2 show the range of distances reached between states of the American West. States were arranged so that the distances between them were as close to the observed differences between the human-carnivore coexistence mentioned, tolerance mentioned or evaluated, number of ecosystem services and number of conflicts reported by articles. A shorter distance between states means greater similarity between them, whereas a longer distance corresponds to a greater dissimilarity. N = 120 (i.e. total number of articles carried out across states; note that one article can be assigned to different states). For this ordination, the number of experiential (a) and emotional (b) human-nature connections was fitted as contour lines using penalized splines (Oksanen et al 2019). The number of connections and the NMDS axis 1 and 2 coordinates were used as a response variable and predictors, respectively. R2 represents the goodness of fit and the P-value indicates the significance of the nonlinear term.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageSocial and ecological factors influencing the research on human-carnivore coexistence, tolerance, ecosystem services and conflicts

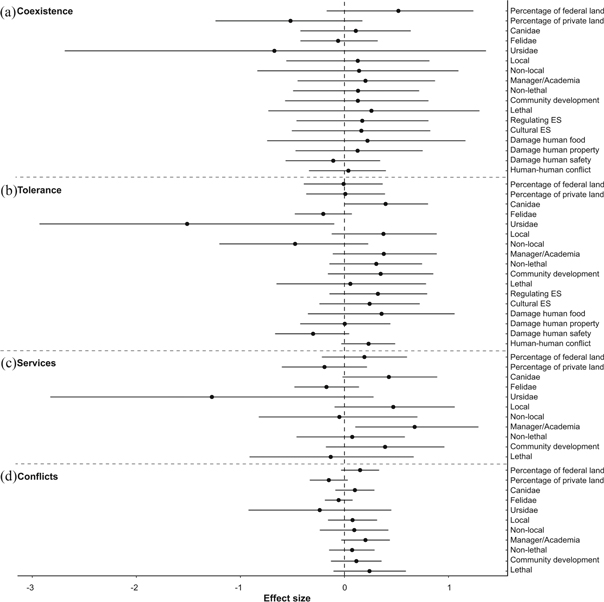

Regarding the number of mentions of coexistence in the reviewed research, we found that the Ursidae family yielded the strongest negative effect but exhibited the highest uncertainty as compared to any other variable (figure 5(a)). Federal and private land showed positive and negative effects, respectively, and low uncertainty (i.e. posterior probability that the credible intervals overlapped zero were 0.069).

Figure 5. Estimated effects (±95% credible intervals) of the social-ecological factors (i.e. predictor variables) that influence (a) human-carnivore coexistence mentioned, (b) tolerance mentioned or evaluated, (c) number of ecosystem services mentioned and (d) number of human-carnivore conflicts mentioned in articles per state of the American West. The effects represent the change in the log of the response variable when the predictor increases by one standard deviation.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageRegarding the number of articles that mentioned or evaluated tolerance in human-carnivore relations research in the American West, we found that several variables can be considered important based on a 95% credible interval (figure 5(b)). Research focused on Canidae, mentions of local and manager/academia social actors, non-lethal management actions, community development programs, regulating services and human–human conflicts had a positive influence on the likelihood to research tolerance toward carnivores, while research focused on Felidae or Ursidae, mentions of non-local social actors and conflicts related to human safety negatively influence the number of articles that mentioned or evaluated tolerance. The number of articles researching the Canidae family, mentions of local actors, manager/academia and community development programs per state positively influenced the number of ecosystem services mentioned. However, the number of articles focused on Ursidae family showed negative effects on the number of ecosystem services mentioned (figure 5(c)). Percentages of federal and private land were the most important variables for the number of human-carnivore conflicts mentioned, with positive and negative effects, respectively. The posterior probability that the credible intervals overlapped zero was 0.050. Finally, mentions of manager/academia actors as well as lethal management actions positively influenced the number of conflicts mentioned (figure 5(d)).

Discussion

What are the current research trends of human-carnivore relations in the American West?

This research shows a growing interest of the scientific community on the human-carnivore relations in the American West (figure 1(a)). This iconic region encompasses several social (i.e. population growth) and ecological (i.e. aridity, topography) characteristics that reveal the complex relationships between humans and carnivores (Jones et al 2019). To date, human-carnivore research has mostly focused on mountains and temperate forests in Colorado and Montana, regions where co-occurrence between humans and large-bodied carnivores (e.g. bears and wolves, figure 1(d)) exist due to extensive farmland activities and recreational use. This finding is consistent with a global assessment of the literature on human-carnivore relations research by Lozano et al (2019) that shows how scientific interest is biased towards large and charismatic carnivore species. This result is also consistent with previous research that shows the influence of charismatic vertebrate species on the conservation research agenda (e.g. Clark and May 2002, Martín-López et al 2009).

Our results indicated a possible bias with regard to the diversity of actors and the diversity of management actions mentioned to mitigate conflicts. On one hand, we found that farmers (subsistence and commercial) and property owners are less mentioned than environmental managers (figure 2(a)). Despite many studies that suggest the importance to engage and integrate all social actors involved in conflicts as a way to achieve coexistence and tolerance toward carnivores (Treves et al 2006, Marchani et al 2019), our results showed that the engagement of actors in human-carnivore research is limited. On the other hand, non-lethal management (i.e. the use of deterrents and zoning livestock, figure 2(b)) is the most reported strategy to mitigate conflicts. However, the effectiveness of different management practices to reduce human-carnivore conflict has been poorly addressed in the studies. The emphasis on non-lethal management actions aligns with previous research that showed the relevance of these measures to mitigate conflicts with carnivores (Eklund et al 2017, Moreira-Arce et al 2018). Our findings also support previous research that identified educational programs and non-lethal measures as the most reported management actions (figure 2(b)). In addition, several studies showed that educational programs and non-lethal measures are successful strategies for fostering coexistence (Nyhus et al 2003, Fernández-Gil et al 2016, Lozano et al 2019).

Finally, we found that research on human-carnivore relations in the American West is biased towards conflicts, mainly damages to food (figure 3(c)). We also found that when research focuses on ecosystem services, it mainly addresses cultural ecosystem services (figure 3(a)). These findings are consistent with the global assessment of human-carnivore relations research conducted by Lozano et al (2019).

What factors are related to mentioning coexistence and tolerance toward carnivores in the research of the American West?

Research on coexistence, tolerance, ecosystem services and conflicts was determined by state-specific social and ecological factors. Bayesian modeling identified percentage of federal/private land, carnivore family, social actors, and management action, as those social and ecological factors explaining how coexistence, tolerance, conflicts and services are addressed in literature (figure 5).

Percentage of federal and private lands exerted a positive and negative effect on the probability of mentioning coexistence in carnivore research, respectively. A large portion of federal land in the US is concentrated in the American West, which has been the subject of debate and controversy about different policies and practices regarding the multiple uses of public lands (e.g. land sparing versus land sharing) (Crespin and Simonetti 2019). On the one hand, a positive effect of federal lands on articles mentioning coexistence is consistent with conservation efforts in states dominated by federal lands, where traditional strategies for wildlife conservation have segregated human activities from remnants of wilderness to avoid further human intervention. On the other hand, the negative effect of private lands suggests the importance of promoting coexistence across states with multi-use landscapes, where space limitation for carnivores demands balancing nature preservation and livelihood protection (Crespin and Simonetti 2019).

Articles mentioning or evaluating tolerance were found to be positively related with the Canidae family (i.e. wolves and coyotes), local actors, managers/academia, non-lethal management actions, community development and human–human conflicts (figure 5(a)). This result can be explained in two ways. First, a large body of literature documents a general positive attitude toward wolves and wolf recovery by the general public (e.g. Browne-Nuñez et al 2015, Killion et al 2019). This tendency has also been shown towards coyotes (George et al 2016). Second, tolerance towards carnivores depends on the type of actor and the management actions suggested. Former research has emphasized the urgent need of conservation planning models for wildlife that integrate the involvement of multiple social actors in decision-making (Kansky et al 2014). Finally, species such as bears and cougars are frequently related to attacks on humans (Penteriani et al 2016, Smith and Herrero 2018, Bombieri et al 2019). This is consistent with factors here identified and shown to have a negative effect on tolerance (i.e. Ursidae and Felidae families, non-local actors and damage to human safety), and can be interpreted as knowledge gaps to advance in the study of tolerance towards carnivores.

A roadmap for advancing coexistence with carnivores in the American West

Based on this study, we propose that future research on human-carnivore relations in the American West should advance knowledge in four main domains: (1) beneficial contributions of carnivores to people (ecosystem services), (2) social-ecological approaches to determine key factors underpinning beneficial and detrimental contributions, including causes of conflicts, (3) consideration of multiple social actors affected by or involved in the management of carnivores, and (4) cross-state collaborative management.

First, this research shows that conflicts with carnivores are much more frequently mentioned in literature than the variety of ecosystem services they provide to people (figure 3). Indeed, ecosystem services provided by carnivores were reported only in 38% of articles. Neglecting ecosystem services provided by carnivores, both in scientific research and outreach activities, can undermine attempts to foster human tolerance for carnivores, which is a critical component of coexistence (Peterson et al 2010, Pooley et al 2017, Ceausu et al 2018, Lozano et al 2019). Therefore, we call for a shift in mindset that recognizes the dual role of carnivores as providers of both ecosystem services and disservices to humans. To promote this shift, we encourage the scientific community to further explore the ecosystem services provided by carnivores to society. For example, a recent review indicated that predators and scavengers can directly benefit humans by reducing disease prevalence, reducing the abundance of species that can injure people (e.g. vehicle-deer collisions), increasing agricultural output, and removing organic waste (O'Bryan et al 2018). This goal might also be reached by revisiting pioneering research conducted in Wester USA on the role of carnivores and particularly top-predator in ecosystem functioning (i.e. trophic cascades, Beschta and Ripple 2009) that translate in key regulating ecosystem services in rewilding landscapes (Kuijper et al 2016). New analytical frameworks have been developed to evaluate tradeoffs in ecosystem services and disservices from carnivores to different recipients (Ceausu et al 2018), although parameterizing these frameworks with empirical data across sites and species are much needed. This idea of the dual role of biodiversity as provider of beneficial and detrimental contributions to people has been acknowledged by the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services under the paradigm of 'nature's contributions to people' (Díaz et al 2018).

Second, we found that current research interest on beneficial and detrimental contributions provided by carnivores in the American West differs according to social and ecological characteristics. Although our results do not indicate a causative relationship between carnivores' contributions and predictor variables, they should be interpreted as different research interest in the study of human-carnivore relations. Therefore, while current research interest on beneficial contributions (or ecosystem services) showed a positive effect on the probability of mentioning species of Canidae and multiple social actors, we found that current research on detrimental contributions (or conflicts) was positively associated with the probability of mentioning species of Ursidae family (figure 5(c)). Thus, future research on human-bear relations needs to further investigate the causes of the lack of research on the beneficial contributions of bears to humans, and needs to consider a wider range of social actors. In addition, we suggest that research on human-carnivore relations develop and analyze a standard, comprehensive set of social and ecological factors, wherever possible, to allow for more direct comparisons across sites and over time. Several studies provide an excellent foundation for enumerating and refining those factors (Lischka et al 2018). Our findings on how different social and ecological characteristics led to differential research interest on ecosystem services and conflicts supports previous calls to apply social-ecological approaches in order to uncover the multiple beneficial and detrimental contributions provided by carnivores to people (Ceausu et al 2018, Lozano et al 2019, Jones et al 2019).

Third, we found that highly relevant actors, such as farmers and decision-makers are less represented in research than others, such as managers, the general public and rural residents (figure 2(a)). Human-carnivore research that overlooks the diversity of social actors involved in human-carnivore management can perpetuate and escalate the conflict with carnivores and create new social conflicts (Hartel et al 2019). To effectively promote coexistence, future research therefore should address the social causes underpinning conflicts, including human–human conflicts, the latter especially can be important but have often overlooked (Dickman 2010, Young et al 2010, Draheim et al 2015). In addition, previous research also shows that the lack of communication among actors involved in specific management strategies leads to ineffective management (Lute and Gore 2014, Browne-Nuñez et al 2015). To create long-term trustful communication between those social actors relevant for the management of human-carnivore relations, future research should promote participatory and transdisciplinary approaches in which multiple actors engage in the design and implementation of a coexistence strategy in the American West (Pooley et al 2017, Hovardas 2018, Lozano et al 2019). Specific methods include collaborative learning, mental models, discursive approaches, and structure decision making (Chan et al 2012, Ban et al 2013). In addition, Hartel et al (2019) proposes to go beyond the simple inclusion of multiple actors and research the deeper levels of values and norms that underpin the actors' actions and behavior. By incorporating norms and values, but also through sustained collaboration with local actors, transdisciplinary approaches can therefore contribute to the long-term viability of human-carnivore coexistence (Hartel et al 2019).

Finally, our results also indicate how land management across states of the American West seems to influence how often conflicts with carnivores are discussed (i.e. more conflicts mentioned on federal lands) (figure 5(d)). Federal lands prevail in the American West, however, agencies that manage these lands, like the Bureau for Land Management and the US Forest Service, have different missions and management approaches, making it very difficult to develop a coordinated strategy for reducing human-carnivore conflicts across federal lands under different jurisdictions and in different states. These obstacles require future research on how to build platforms for collaboration among key actors and institutions across states in order to foster coexistence in the American West. Although the formation of cross-state platforms might lead to new conflicts (Redpath et al 2017), such platforms could also represent new institutions by which multiple actors can embrace the challenge of coexisting with carnivores and engage to find shared solutions (see also Smith et al 2016, Hartel et al 2019). In this context, our proposal goes beyond including different sectors and actors since it aims to promote cross-state and transboundary collaborative management in the American West.

Conclusions

Our study has demonstrated that current research on human-carnivore relations in the American West has several knowledge gaps. These knowledge gaps include: (1) knowledge about the ecosystem services provided by carnivores, particularly regulating and provisioning, (2) knowledge on the social roots that underpin intolerance and coexistence, (3) information on how relevant actors, such as farmers and decision-makers, relate with carnivores, and (4) effectiveness of different management practices to reduce human-carnivore conflicts and foster coexistence. Based on these findings, we call for a research agenda that applies social-ecological and transdisciplinary approaches to understand and manage human-carnivore relations in the American West. This agenda, in turn, should focus on four main themes: (1) the dual role of carnivores as providers of both beneficial and detrimental contributions to people, (2) social-ecological factors that underpin the provision of beneficial and detrimental contributions, (3) inclusion of diverse actors affected by carnivores or involved in their management, and (4) cross-state collaborative management. This agenda should be revised under an adaptive management framework in a context of rewilding and global change.

Acknowledgments

MEG was supported by a research contract from Sistema Nacional de Garantía Juvenil co-funded by the Social European Fund and the Junta de Andalucía, Spain (PID_UAL_2018/001). AJC, NHC, and JMRM were funded by the NSF Idaho EPSCoR Program under award number IIA-1301792 and OIA‐1757324. MM and AFM were supported by Ramón y Cajal research contracts from the MINECO (RYC-2015-19231 and RYC-2016-21114, respectively), ZMR by a postdoctoral contract from the Generalitat Valenciana (APOSTD/2019/016) and ACA by a postdoctoral contract of Programa Viçent Mut of Govern Balear, Spain (PD/039/2017).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.