Copyright 2010 Robert D. Shepherd. All rights reserved. NB: I wrote this back in 2010. Just getting around to posting it. The material I cover still stands, I think, though I might do some slight revision at some point.

Think of a time when you were swimming—at the beach, in a swimming pool, in a river or lake. Take a moment to close your eyes and picture the event. (What follows will be better if you actually do this.)

About half the time, when people recall such a memory, they picture themselves from the point of view of a third-person observer. I think of a time when I went to St. Martin and immediately after checking into my hotel, went for a swim. I see myself running down the exterior hotel stairway, crossing the sand, plunging into the sea, and taking long, crawling strokes in the turquoise water. This memory is doubtless influenced by a photograph I have from the time, one taken from the hotel’s second-floor balcony by my then wife.

First- and Third-Person Memory

Being a third-person memory, my recollection is not, of course, precisely what I experienced. I could not, obviously, have been a third-person observer of myself! In the present, we see the world not from the third-person perspective but in the first person, from the inside looking out. As I sit writing these words, I see the monitor in front of me, a cup of coffee, and if I glance down, the tip of my nose and my fingers at the keyboard. But if I remember this experience later, I’m likely to remember it not from the inside but from the outside: I’m likely to see in my mind’s eye the whole of me, sitting at a computer, writing. First-person memories tend to be phenomenally rich, whereas third-person memories tend to be of more extended duration, to be narrative (which is a clue, perhaps, to their construction).[1]

Third-person autobiographical memories should give us pause because they are, to some extent, confabulations, or reconstructions, part real and part imaginary. They are not simple, retrieved events, pure sensory experience as taken in at the time (what psychologists call field memories) but, rather, stories that we tell ourselves, just-so stories about how things must have been. The philosopher Eric Scwitzgebel has theorized that our tendency to create third-person memories is related to our heavy consumption of movies and television, that we have learned to play movies in our heads, just as we now report dreaming in color, whereas in the 1950s and earlier, people most commonly reported dreaming in black and white.[2] Whether or not that is so, third-person memory is certainly quite common now. The naïve view of memory is that it is like a video recording in the head: this is what happened to me. I know. I was there. But as third-person memories demonstrate, we humans are quite capable of deceiving ourselves about what we remember.

Suggestibility and “Recovered” Memory: Deference to Authoritative Accounts

Sometimes our self deception can be about entire events. In a famous experiment, psychologist Elizabeth Loftus and her research associate Jacqueline Pickrell gave subjects booklets containing three stories from their pasts. The stories were supposedly gleaned from interviews with the subjects’ relatives. In each case, however, one of the stories, about the subject’s getting lost in the mall at the age of five, was false. In follow-up interviews, Loftus and Pickrell asked their subjects how much detail they could remember from each event. Unsurprisingly, subjects recalled with some detail about 68 percent of the true events. What was surprising was that about 29 percent of the subjects reported recollections of the false event, often providing elaborate detail about it.[3] It’s an experiment that has been repeated numerous times by various researchers with similar results.

There’s little consequence, of course, to having a false memory of being temporarily lost in the mall, but not all false memories are so benign. Years ago, when I was living in Chicago, a lawyer friend told me of a case she had taken on earlier in her career. Her client was an elderly African-American man who worked as a janitor in a largely white preschool in a largely white church of which the African-American man was a deacon. The man stood accused of molesting some of the students in the preschool, and a story about the molestation appeared on the front page of one of the Chicago papers. As the case developed, the children’s stories became more and more bizarre. They told of being burned in ovens and having large objects inserted in their orifices, but there was no physical evidence of this supposed abuse. In the end, psychologists ascertained that the children had confabulated. They had been visited by a social worker who gave them a demonstration about abuse using anatomically correct dolls. The mostly white children, scared anyway by a person who was older and not of the same race and who often appeared mysteriously from around corners, made it all up in their discussions with one another. What started as just-so stories, like the ones that kids tell about abandoned houses and dark closets and other objects of their fears, became magnified and reified, or given actuality. All charges were dropped against the elderly man, but his life was ruined. Abuse of children is unfortunately common, but in this case, no actual abuse had occurred.

Human suggestibility with regard to memory can have devastating consequences. Lawrence Wright’s disturbing and gripping book Remembering Satan[4] tells the story of Paul Ingram, a sheriff’s department deputy and Republican Party county chairman in Washington state who fell victim to false accusations that he had molested his daughters when they were young and had later subjected them to Satanic ritual abuse. The daughters had fallen under the influence of a pair of psychologists who coached them through the process of “recovering” supposedly forgotten memories of abuse, and as a result, Ingram actually came to believe that there must be some truth to what the daughters were saying, was falsely convicted of molestation, and spent years in prison for crimes he didn’t do. As in Salem, during the witch trials, the daughters’ imagined experiences grew in complexity until they took in a great many townspeople involved in an abusive Satanic cult. Eventually, other psychologists were called in by the courts, and the whole edifice of the daughters’ fabrications, under the influence of their psychologist Rasputins, fell apart.

Supposedly repressed and recovered memories have played a key role in many such cases in the United States and elsewhere, so many, in fact, that the False Memory Syndrome Foundation was established to assist victims of false memories planted during therapy, though the work of this foundation and the validity of recovered memories remain contentious. A large-scale study by Elke Geraerts and others of Harvard and Maastricht looked at three types of memories of child abuse: ones continuously remembered, ones spontaneously recovered in adulthood, and ones recovered in therapy. Spontaneously recovered memories were corroborated about as often as continuous ones (37 percent of the time and 45 percent of the time, respectively), but recovered memories were not corroborated at all. The study by Geraerts and her colleagues suggests both that memories of traumatic events are extremely faulty and that people are extremely susceptible to manipulation of their memories.[5] Though recovered memories are questionable, there is no question that child abuse itself is a common problem, and the difficulties that people have with their memories work both ways. It can simultaneously be the case that recovered memories are suspect AND that memories of real abuse are often buried or whitewashed.

Memories of Misinterpreted Experiences

A number of years ago, I was living in Massachusetts and was single and dating. Having met in my dating life a few young women who were dealing with significant psychological issues, including bulimia and depression, I thought I might benefit from a class in the psychology of women offered by the Harvard Extension Program. So, I took the class, taught by a renowned feminist psychologist, and there I met a young woman who was convinced that she had been abducted by aliens. As it happened, around the same time, John Edward Mack of the Harvard University School of Medicine had studied sixty people who claimed to have experienced alien abduction. Dr. Mack spoke, once, with the woman I met, but she was never one of his patients or major research subjects. Interestingly, Dr. Mack reported that “The majority of abductees do not appear to be deluded, confabulating, lying, self-dramatizing, or suffering from a clear mental illness.”[6] The woman I met fit Dr. Mack’s description. She was bright, thoughtful, normal in every way, but she seriously believed, was in fact certain, that she had been abducted numerous times. Her stories of these abductions followed the classic plot line: She would awaken to find herself paralyzed, with creatures standing around her bed. She didn’t use the term, but her description fit that of the Grays, as UFO buffs call them, small aliens with big heads, large eyes, childlike bodies, and four long, large, ET-like fingers on each hand. The Grays would mill about the bed a bit. Then, the woman would feel herself lifted up in a beam of light and mist. The beam of light would carry her onboard an alien spaceship, where the aliens would perform various experiments on her. All the while, she would be immobile but perfectly conscious and completely, abjectly terrified. Eventually, the Grays would render her unconscious and she would awaken in her own bed. I shall never forget what this woman told me about these experiences: “Don’t tell me I imagined these things. I know they happened. I was there, just as I am here with you right now.”

Various explanations have been offered for the alien abduction experience. One is that the pineal gland produces small amounts of the psychotropic compound dimethyltryptamine, or DMT, which is known to cause self-appointed psychonauts to experience alien presences. The late Terrace McKenna, an enthusiastic advocate of the use of hallucinogens, wrote and spoke often of the alien “machine elves” whom he met and spoke with while under the influence of DMT. The most widely accepted explanation of the alien abduction phenomenon, however, is that during REM sleep, our brains protect us from acting out our dreams and so possibly hurting ourselves by inhibiting, post-synaptically, the operation of motor neurons, thus preventing the stimulation of our muscles. By this account, abductees awaken to a hypnagogic, or dreamlike, state, and find themselves paralyzed. In their susceptible, liminal condition, somewhere between waking and sleeping, their brains confabulate, making up a story to explain why they are in this pickle, and that story, that waking dream or nightmare, is what they remember. Because the “abductees” live in a time in which big-eyed, big-headed Gray aliens are as close as the local video store, their waking nightmares sometimes take on a form that they have borrowed from the popular culture. In Medieval times, such dreams took the form of succubae or witches. In fact, the story of a witch waking someone and riding him through the skies is what gives us our very word nightmare. (Of course, another possible explanation of alien abduction is that people are sometimes abducted by aliens, but that’s not a terribly parsimonious explanation, is it?)[7]

The Internal Story-Teller

Dreams can be quite bizarre. For a time, I kept a dream journal. In one of the more unusual dreams in that journal, I was in an airplane, a small prop plane that was flying into the island of Cuba, but in the dream, the island was a large, white-frosted sheet cake floating in a cliché of an emerald sea. Later, it was easy enough for me to piece together the sources of this dream. I had just returned from a trip, one leg of which was in a small prop plane. The day of the dream, there had been a news story about the illness of Fidel Castro. I had recently been to a wedding where there was a large cake (though not of the sheet variety—that must have been an adaptation of the cake idea to the topography of an island).

A widely held theory of dreaming is that it occurs as the mind sorts out and catalogues recent events.[8] Recently used neural pathways fire, and our pattern-making brains attempt to make sense of these random firings, putting them together into a coherent narrative. If the pathways that are firing are wildly divergent, we get these surreal dreams—islands that are wedding cakes. In another dream, I was again on an airplane and a large and, of course, red orangutan sitting next to me offered me a cigar. Come to think of it, that’s not so bizarre. I often find myself on airplanes sitting next to someone who is distinctly simian.

Dreams, alien abduction narratives, and confabulations great and small are revealing because they remind us of something very important about how people work: We are storytelling creatures. It’s not just when we are sleeping or in hypnagogic states that our brains are busy making sense of the world by telling us stories. It’s all the time. And when we get new information—we see a picture of our former selves or a relative tells about our getting lost in the mall at the age of five—our brains work to integrate that information into the narrative of our lives that we carry around with us. We take in sensory experiences and other information, and then we dream weave it into a narrative. That narrative, as much as the actual sensory experiences themselves, becomes memory, and our memories are, to a large extent, who we are. I believe myself to be a particular person with a particular history. I am the boy of five padding in his Dr. Denton’s across the floor of his grandparents’ upstairs bedroom at night to get a glimpse of a Ferris wheel, far across the darkened cornfields, turning red and green and golden in a dreamlike distance. I am the sixteen year old in the car at the drive-in movie trying to get up the courage (I never did) to kiss the amazing girl whom I never in my wildest dreams thought would go out with me. I am the hopeful applicant for his first editorial job, sitting across the desk from the renowned Editor-in-Chief staring at me over his broken reading glasses, which he has cobbled together with a bit of scotch tape. A self, an identity, is the summation of a great many such stories.

Suggestibility and False Memory 2: Deference to Social Sanction

But how true are the stories? Memory is notoriously faulty. Consider the following experience from another psychology class, one that I took in my freshman year in college: I was sitting in a large auditorium with some two hundred or so other students, listening to the professor, when costumed people burst in through the back door of the lecture hall, shouting and making a disturbance. They ran down one aisle (as I remember it), yelled a few things, leapt onto the stage, scattered the professor’s notes into the air, and then disappeared off the stage and through a side doorway. The event, of course, had been staged. The professor had us all write down what had just happened, and then we compared notes. My fellow students in the auditorium didn’t agree on much of anything at first—on how many people there were, on what they were wearing, on what they said, on what they did. Among other things, this event was a dramatic demonstration of the inaccuracy and inconsistency of eyewitness accounts. We humans have difficulty with the accurate recollection of experience. We’re not very good at it. Furthermore, we all have a tendency to confabulate, especially in social settings, where we have an all–frequent tendency to fall into group think and to start believing that we remember what other people confirm (We shall return to this subject later in this book). In the disruption demonstration/experiment, as the discussion continued, students began separating into groups—the ones who were certain that there were three intruders and those who were equally sure that there were four, for example. For many people, their certainty about what had happened increased over time, as they rehearsed it, and during this process, there was a lot of “Hey, yeah, I remember that too” going on.

Filling in the Gaps

Perhaps you think that you are not a confabulator, not someone who adds details to fill out the story and certainly not someone who will remember something differently because of someone else’s suggestion. Lest you fall into that trap, let me remind you that confabulation is a central part of sensory experiences themselves. Notoriously, we all have the feeling that we see the entire visual field before our eyes, but in fact, we all have blind spots in our visual fields caused by the fact that our retinas are interrupted in an area called the optic disc, where ganglion cell axons and blood vessels pass through our retinas to form our optic nerves. We view the world as continuous because our brains confabulate, filling in the missing details, telling us just-so stories.

But it’s worse than that. It’s not just that our perceptual systems regularly and systematically fool us. Memory is slippery. It’s susceptible to error because of drowsiness, illness, inebriation, inattention, stress or other strong emotion, and weakening or disappearance over time. A couple of other problems with memory are particularly interesting. First, what goes into memory is severely limited. For a long-term memory to be formed, it first has to go through the narrow funnel of working memory. In a famous essay called “The Magical Number Seven Plus or Minus Two,” the psychologist George Miller pointed out that only seven or so distinct items can be held in working memory at any given moment. That’s why, for example, telephone numbers are seven digits long. We can increase this “working space” in memory by chunking, by putting items together into groups. So, it’s much easier to remember the string

S E T R K T A I M A R F A A R N

if we rearrange the letters and break them up into IM A STAR TREK FAN. But the point remains that of the innumerable things happening at any given moment, only a precious few gain admittance to working memory and thus have any hope at all of being transferred into short-term memory and from there into long-term memory.[9] The rest we assume, or fabricate, to put it less euphemistically, in later recall. Well, I was in my living room, so I must have been seeing this, that, or the other, our brains might as well be saying, though, of course, the brain does this unconsciously. In short, we actually attend to very few items at any given moment, but our brains are so constructed as to integrate what we were actually attending to with what we know, or think we know, about the world to prepare a long-term memory that is whole and consistent and present THAT confabulated memory to consciousness. If the long-term memory is of the third-person type, that confabulation is obvious, but we also confabulate first-person, field memories. It’s how we are made.

Inattentional Blindness

An important but often unremarked consequence of the limitations on working memory is inattentional blindness. As we have just seen, we can, at any time, attend only to a few things. So, the rest we are blind to. In another famous experiment, Daniel Simons of the University of Illinois and Christopher Chabris of Harvard showed subjects films of people passing a basketball around and asked them to count the number of passes. In the course of the films, a woman walked into the scene, sometimes carrying an umbrella and sometimes wearing a gorilla suit. Dutifully attending to their task, most subjects didn’t see these oddities—the umbrella or gorilla in the midst of the basketball game! Memories typically have a wholeness about them, but most of that wholeness is imagined. When our brains do their work, telling us our stories, they make use of the material that we actually stored, and they fill in the rest. And sometimes they miss really interesting or important stuff, like the 800-pound gorilla in the room!

History as Confabulation: Narrativizing as Interpretation, or “Making Sense”

But it’s even worse than that. Not only does memory fail us, and not only do our brains commonly and automatically fill in the gaps to make up for those failures, but we also, because of our story-telling natures, impose upon what we remember, or think we remember, narrative frames that serve to interpret and thus make sense of the events of our lives. Over forty years ago, the historiographer Hayden White wrote an influential essay, “The Historical Text as Literary Artifact,” in which he argued that when we discuss an historical event, we inevitably select some aspects of that event and not others, for time and scholarship are both limited, and every event might as well be infinitely complex. That much of White’s thesis is uncontroversial. What is controversial, and of enormous consequence, is White’s contention that we claim to have understood an historical event only after we have imposed upon it a narrative frame—an archetypal story, typically with a protagonist and antagonist, heroes and villains, a central conflict, an inciting incident, rising action, a climax or turning point, a resolution, and a denouement. The narrative frame exists not in the events themselves, but in our minds, as part of our collective cultural inheritance. Joseph Campbell famously proposed in The Hero with a Thousand Faces that a great many stories from folklore and mythology have a common form: a young and inexperienced person, not yet aware that he is a chosen one, sets out on a journey. He encounters a being who gives him a gift that will prove extremely important. He undergoes a trial or series of trials, succeeds as a result of his character and the gift, and emerges with some boon that he is able to share with others on his return. Joseph Campbell’s monomyth is one example of the kind of archetypal, interpretive narrative frame that gets imposed on events.

Returning to Hayden White’s thesis, to one person, the founding of Israel is the story of an astonishing people, dispossessed, scattered to the winds (the setting out on the journey), subject to pogroms and persecutions (trials), who astonishingly, and against incredible odds, maintain their cultural identity, keep the flame of their nationhood alive by teaching every male child to read (the gift), suffer a horrific holocaust (more trials) and then, vowing never to allow such a thing to happen again, reclaim their historical birthright and carve out a nation in the midst of enemies, even going to the extent, unparalleled in human history, of reviving a scholarly, “dead” language, Hebrew, and making it once again the living tongue of everyday social interaction (the boon). I, myself, find this story, thus told, quite compelling and moving. In a very different version of these events, an international movement (radical anti-Semites would say “conspiracy”) leads to an influx of Jews into Palestine after the Second World War, and these Jews, taking advantage of a vote in the newly established United Nations, declare themselves a state and forcibly expel over 700,000 native Arabs from their homes. Both stories are true. The telling depends, critically, upon which events one chooses to emphasize. Overemphasis on one set of facts confirms some people in an obstinate unwillingness to make concessions necessary to secure a lasting peace. Overemphasis on the other set of facts leads other people to horrific acts of terrorism.

Consider, to take another example, this quotation from a white, American man of the nineteenth century:

“I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in anyway the social and political equality of the white and black races—that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.”[10]

Now consider this quotation, also from a nineteenth-century white, American male:

“On the question of liberty, as a principle, we are not what we have been. When we were the political slaves of King George, and wanted to be free, we called the maxim that ‘all men are created equal’ a self evident truth; but now when we have grown fat, and have lost all dread of being slaves ourselves, we have become so greedy to be masters that we call the same maxim ‘a self evident lie.’”[11]

The first of these statements, from a contemporary perspective, seems outlandish and shocking, the second reasonable and evident. You may have guessed, however, or may know, if you are a student of history or have glanced at the endnotes, that these two men are the same person: Abraham Lincoln, whom we remember as the “great emancipator.” Our view of Lincoln’s view depends, critically, on which of his statements and actions we attend to and from what parts of his life, and our view also depends on what narrative we tell based upon our selections and how nuanced that narrative is. Lincoln was, indeed, an early opponent of slavery and considered it an evil from an early age, but his views on the subject were far from monolithic, and they evolved over time. In short, they were complicated. And that’s always true of history. Whenever we look closely at some past event, we find that it is a lot more complex than are the simplistic accounts (one might call them myths) typically presented in high-school “social studies” textbooks.[12]

The Punch and Judy Show: Making Sense in Relationships

What Hayden White says of history is true of our personal histories too. What makes the stories that we tell ourselves about our lives into stories and not just collections of facts is that we selectively recall facts and we impose narrative frames upon them. The central character is a given. Each of us is the protagonist in his or her own tragicomedy. But we also identify antagonists and conflicts and moments of crisis and resolution. We create causal maps to explain why things happened as they did, often involving imputed motivations. So, in the stories that we tell ourselves from our own lives, we do not simply recall events; we interpret them. Two people, let’s call them Punch and Judy, are in relationship. They both recall an evening when they went to the theatre. Punch has decided that Judy is stubborn, that she must have her way about everything. So, when his brain reconstructs a memory, it automatically constructs it from bits and pieces, using that guiding principle. He conflates several actual times, over thirty years, in which Judy acted in a stubborn way and puts them all into the memory of that one evening. She refused to go to the show Punch had bought tickets for until her friend talked about great it was. She insisted on changing seats to sit on the outside. She refused to let him out until intermission, even though he needed to go to the bathroom. She insisted afterward that the leading lady was wearing a yellow dress at the beginning of Act II instead of a green one. One of these actually happened on that evening. Two never happened. Two happened, but at different events over the years. Judy, on the other hand, has decided that Punch often makes a spectacle of himself in public—that he has no decorum or tact. So, she has her own list of “things that happened on that evening at the theatre”—he interrupted the show and caused a scene by getting up to go to the bathroom ten minutes into Act I. He insisted on wearing, that evening, that ridiculous-looking jacket with the tux-like lapels. He told the waiter at dinner afterward how terrible the leading lady was, and that waiter was the leading lady’s good friend. And so on. But again, some of the things she remembers from that evening happened at other times or didn’t happen at all. They are confabulations that fit a general view that she has come to.

And this is common when relationships are in the process of failing. The day comes when one in the couple decides that the other is ×—whatever × is—and everything that happens after that is confirmation. The “evidence” grows that the situation is intolerable, and the person decides that the relationship is over, even though much of this “evidence” is confabulation.

We all are the central characters in our own stories, and we have a tendency to tell those stories to ourselves in a self-serving way, to remember our moments of glory and to forget or downplay those times that weren’t our most shining hour. And sometimes, the stories that we tell, impute personality traits or motivations to others that are absent or barely there. Often, those imputations fuel resentment that festers and makes us cynical or mean-spirited when we would really be much better off to let it go, to move on, or, if we can’t, to consider (at least) the possibility that our interpretations are interpretations, not verbatim transcripts of reality.

Writing Our Stories v. Having Them Write Us

The stories from our lives are not created equal. Rather, we all tend to run a few critical, defining stories in our heads. Sometimes, these stories have only a tenuous connection to third-person, objectively verifiable reality, and sometimes, they can be terribly, terribly damaging, as when a person tells himself, over and over, a story of his or her victimization and in so doing becomes a perpetual victim. A number of clinical psychologists have recognized this and have created something called cognitive narrative therapy. The idea is to assist people to alter the stories that they tell themselves in crucial, life-enhancing ways. So, the victim of childhood molestation learns to think: No, I was not responsible for the liberties that my relative took with me when I was a child, and no, I was not at fault when he was found out. I was a child, and he was a pedophile, a person with a deep and terrible sickness. It was not my fault, and the story that I’ve been telling myself about that is deeply flawed.

As a senior in college, having finished the requirements for a degree in English, I experienced a crisis of faith. I had noticed in my reading of books, essays, and journal articles in my field, that literary critics and theorists typically devoted about a third of their energies to their topics, a third to displaying their erudition, and a third to protecting their intellectual turf. Did I really want go to graduate school and become an English professor and spend my life writing journal articles with titles like “Tiresias among the Daffodils: The Hermeneutics of Sexual Identity in Jacobean Pastorale?” Such articles were typically read by ten other scholars whose main motivation for doing so was to gather ammunition to refute what was said in the infinitely more brilliant articles that they were going to write. This didn’t seem a worthy use of a life. Literary critics, take note: Many of the tools in your workshop, developed for the purpose of literary analysis, are extremely valuable for making sense of our life stories and for subjecting those to criticism. So, if you are looking for a way to make what you do even more relevant, that’s an idea. Many literary types already know this, of course.

We’ve seen that we are (To how large an extent? Try this for homework.) the stories that we tell ourselves about our lives. Some of those stories are even partially true! We’ve seen that inevitably our stories are based upon fragmentary evidence and are at least partially confabulated as a result of our storytelling gifts, our ability to “fill in the gaps.” We’ve also seen that sometimes we can benefit enormously from critical analysis of our own collection of life stories, and particularly of those stories that we replay a lot. If we are our stories, then we are, all of us, at least partially fabrications. That’s an unsettling idea, but it’s also liberating, for we can learn to take our own life stories with a grain of salt and so gain nuance in our understandings of ourselves and of others. And, instead of engaging in another Punch and Judy show with a partner or friend when we have differing memories of some event, perhaps we can have some understanding of how these differences arise and less certainty about the superiority of our own narratives. I’ve begun this work on uncertainty with an examination of what we know of ourselves because surely, of all that we know, we know ourselves best. But even there, as we have seen, there is reason for skepticism, for significant uncertainty, and that skepticism, that uncertainty, can be extremely healthy.

[1] Georgia Nigro and Ulric Neisser, “Point of View in Personal Memories.” Cognitive Psychology 15 (1983), 467-82.

[2] “Remembering from the Third-Person Perspective?” The Splintered Mind: Reflections in Philosophy of Psychology, Broadly Construed. Blog entry. June 6, 2007. http://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2007/06/remembering-from-third-person.html

[3] Add footnote to Loftus.

[4] Wright, Lawrence. Remembering Satan: A Tragic Case of Recovered Memory. New York: Vintage, 1995.

[5] Geraerts, Elke, et al. “The Reality of Recovered Memories: Corroborating Continuous and Discontinuous Memories of Childhood Sexual Abuse.” Psychological Science. Vol. 18, no. 7. Jul7 2007, 564-68.

[6] Harvard University Gazette, July 24, 1992.

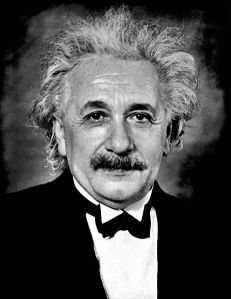

[7] Parsimony as a criterion for judging potential explanations is generally attributed to the medieval scholar William of Ockham, to whom is often credited the statement that Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitate, or “Entities should not be multiplied unnecessarily.” As is often the case with famous quotations and their attribution, this one does not come from Ockham, though it is likely that Ockham would have approved of it. The principle of parsimony, often referred to as Ockham’s razor, is that one should look for the simplest explanation that fits the facts. There’s no reason, of course, why explanations have to be simple. Events, for example, often have multiple causes. But there is good reason for not making explanations too complicated, for one could make up an infinite number of complicated but false explanations to fit any set of facts. Similarly, Einstein is often credited with having said, “Make things as simple as possible, but not simpler,” which I have not been able to verify, though he did say, in a lecture given in 1933 that “It can scarcely be denied that the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience.” (“On the Method of Theoretical Physics.” Herbert Spencer Lecture, Oxford, June, 1933, in Philosophy of Science, vol. 1, no 2 (April 1934), pp. 163-69.)

[8] See, for example, Girardeau, Gabrielle, et al. “Selective suppression of hippocampal ripples impairs spatial memory.” Nature Neuroscience, 2009; http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/vaop/ncurrent/abs/nn.2384.html

[9] All this is made much more complicated by the fact that we are continually taking in information on some level and processing but not attending to it. By working memory, here, I am referring to the new information that we are capable of consciously attending to.

[10] Abraham Lincoln, Debate with Stephen A. Douglas at Charleston, Illinois, 1858

[11] Abraham Lincoln, Letter to George Robertson, 1855

[12] See, for example, Loewen, James W. Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. New York: The New Press, 2005. The title is, of course, an exaggeration. Oops. And Loewen is himself perfectly capable of getting some things wrong. The book remains, however, an interesting, amusing, occasionally enlightening and sometimes disturbing read. I myself got a lesson, years ago, in how difficult the work of an historian is when I created a series of books called Doing History. The idea behind the books was to coach kids through examining primary source materials—maps, letters, ship’s logs, oral histories, that sort of thing. My colleagues and I decided that we wanted to be very serious about getting our facts right. We didn’t want to produce books like the American history book that said that Sputnik was a nuclear device or the popular biology text that said that blood returning to the heart was blue! (One could go on and on multiplying these examples.) We soon found, though, when we sent to work verifying our facts, that as often as not, the facts we assumed to be true were disputed or questionable or flat-out wrong, and at some point, often, we just had to give up and use other material!