The Germans have a reputation for designing quality machinery, and in fact, they did design far-reaching advanced aircraft types during World War II. While there is a lot of crazy talk about UFOs and other nonsense, what the Germans actually created during the war was in fact so far ahead of the other powers that it almost did enter the realm of science fiction. These were the Luftwaffe Super-Weapons.

Advanced Aircraft that Flew

The Third Reich had quite a few advanced aircraft that flew. There were not mere scribblings in a notepad, they were built and used. Some were several decades ahead of their time.

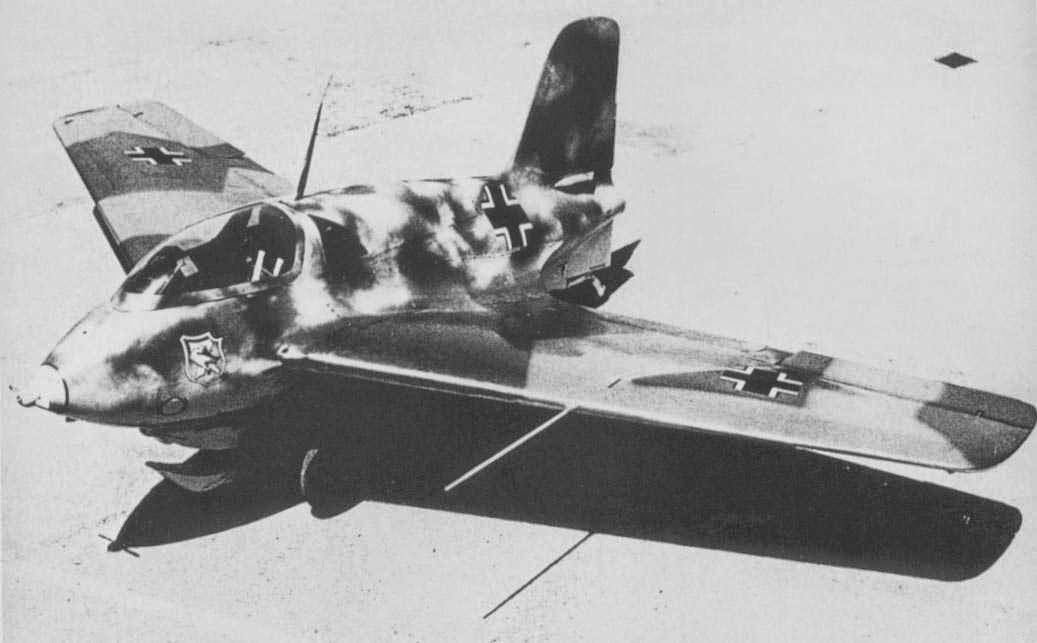

ME 262

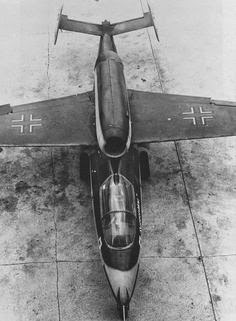

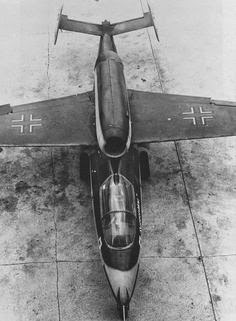

The Messerschmidt Me-262 fighter is the most famous of the Third Reich's jet aircraft. It deserves its fame, although it was just one of several operation jet aircraft that were used in combat in 1944-1945.

|

| The Me 262 has become a favorite of modern enthusiasts. |

The Messerschmitt Me 262 Schwalbe (English: "Swallow") was the first operational jet fighter plane. Although it only appeared in the closing months of the war, the ME 262 was far from a last-ditch move of desperation or panacea fantasy project, of which there are many other examples. Instead, it was a carefully developed and extremely capable machine that actually did what it purported to be able to do, and did it very well.

The Allies also had jet aircraft either in development or in provisional use behind the front lines during the closing months of World War II. None saw combat, and none matched the capabilities of the ME 262. Its pilots claimed 542 kills, which did not affect the strategic situation but did badly scare Allied planners and also likely saved the lives of some German civilians.

The Germans built their first jet engine in 1936, designed by Hans Joachim Pabst von Ohain. A test plane, the Heinkel He 178, flew in 1938. Development on a fighter version began at once, led by Messerschmidt designers Dr. Woldemar Voigt and Robert Lusser.

It took time to develop the fighter, and the hold-up was the engines. The entire design had to revolve around the fragile new engines. Also, the Germans were overconfident and did not think they would need the plane quickly, as the war was going well. The design team was slashed in February 1940. Other aircraft were easier to make and needed immediately. Nevertheless, progress continued, and the first successful jet-powered flight was on July 18, 1942.

Another hold-up was interference by Adolf Hitler, who wanted a ground-attack bomber rather than another fighter. However, this only resulted in a variant being designed, the Sturmvogel, and development on the main fighter version continued regardless of the wishes of higher-ups. The engines were the problem that had to be overcome, not Hitler. Those who claim that he personally kept the aircraft from appearing in the skies are misguided.

|

| A fleet of ME-262s ready to go, parked under the open sky - no worries in the world. |

The initial ME 262s were organized into Erprobungskommando 262 at Lechfeld near Augsburg in the spring of 1944, based at Achmer and Hesepe (Bramsche). The first combat success was on July 26, 1944, when a ME 262 damaged (and may ultimately have caused the destruction of) a Mosquito bomber. This was significant, as the fast and nimble Mosquito was considered a difficult aircraft to destroy. Around this time, the unit became operational as an Einsatzkommando known as Kommando Nowotny after its commander, Major Walter Nowotny. The Allies noticed the new fighters appearing in the skies over Germany that August and this unexpected development began to worry USAAF General Carl Spaatz and the intelligence boys.

Sporadic ME 262 missions continued through the fall. Nowotny himself was shot down on November 8, 1944. The unit was reorganized into a fighter squadron (Jagdgeschwader), JG 7, commanded by Macky Steinhoff, but it was withdrawn until January 1945. Lieutenant General Adolf Galland took over a unit in February 1945 and created a "superstar of the Luftwaffe" unit, staffed by the best pilots. This unit hit the Allies hard in March 1945, operating in numbers for the first time and scoring kills. One Luftwaffe pilot, Hauptmann Franz Schall, was credited with 17 kills, and another, Oberleutnant Kurt Welter, claimed 25 kills. Oberstleutnant Heinrich Bär claimed 16 kills.

As always with any good plane, weak pilots were still shot down, while the best racked up the kills. That any pilots could creditably claim that many kills in the short time that the ME 262 squadron flew is remarkable and illustrates the power of the design.

Armament varied. Some versions had four 30 mm MK 108 cannons, others only two. Some were armed with rockets, 24 x 55 mm R4M rockets. The ground attack versions, which were not successful, carried 2 x 250 kg bombs or 2 x 500 kg bombs.

The ME 262 was superior for its time, but it was far from perfect. It had a relatively short combat range, and the engines were vulnerable to enemy fire. The engines themselves burned out quickly and only lasted a certain number of hours before having to be replaced.

Perhaps the best test pilots of all time, Captain Eric "Wink

le" Brown is one of aviation's legends. He

was asked in 2010 (minute 6:30):

"Was there any German aircraft that you evaluated during the war where you thought, 'this is so much more advanced we should just put it into production ourselves in the UK'?"

"Oh Yes. The one which was... which staggered us, frankly, with its quantum jump in performance was the jet - twin jet - Messerschmidt 262. When I tested it here at Farnborough, it was 125 miles an hour faster than any Allied fighter. Now, this puts it in a league by itself, and it was virtually untouchable. And that rattled us, frankly, to find that, and it's just as well that they were unable to produce them fast enough to really make a nuisance of themselves. Anyway, at this stage in the war, which is very late, the Germans were running out of pilots and running out of fuel, but the thought of them perhaps having pilots and fuel and a lot of these jets was a bit sobering."

Several ME 262 survive, in museums and in private hands. Some replicas are in flying condition. The ones being built today are considered part of the original production run begun during World War II.

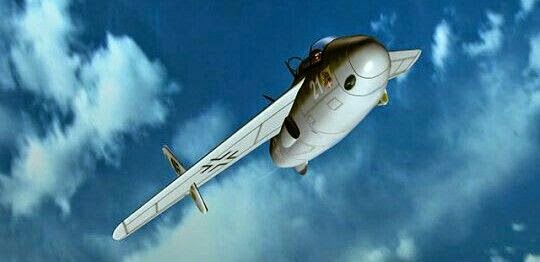

Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet

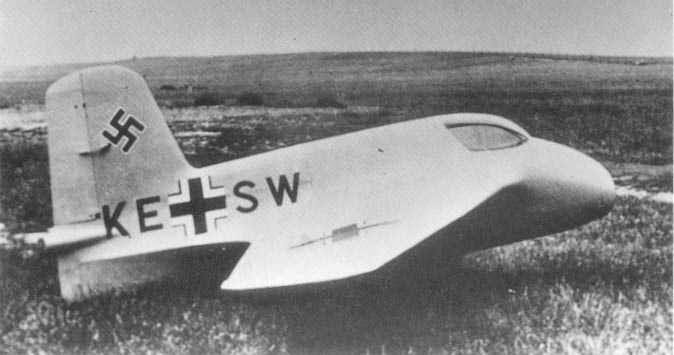

Of all the planes of the Second World War, the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet was the craziest. Sure, there were fanciful designs that didn't stand a chance of ever being made, but the Komet was, in fact, made. Not only was it made, but it became a major effort of the Hitler regime, an effort that was completely pointless and utterly wasted.

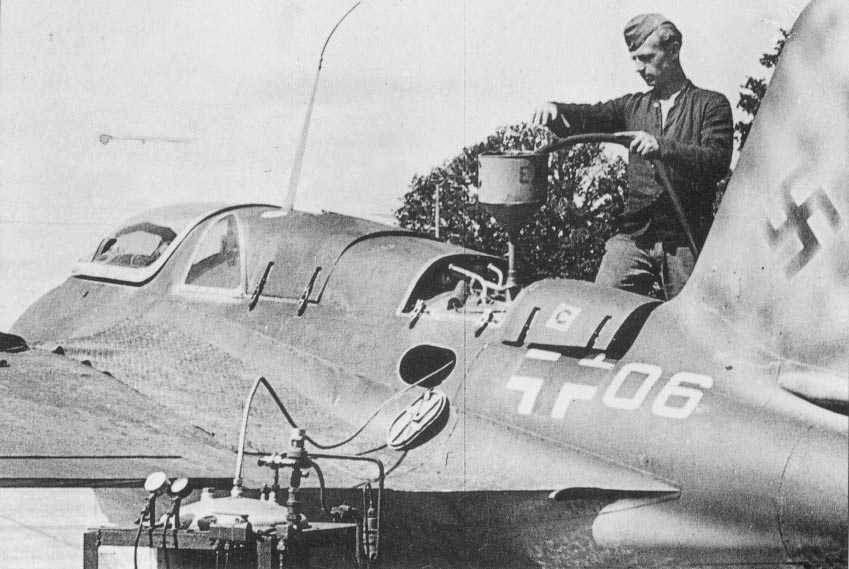

While the ME 163 has all the appearance of being a last-ditch aircraft that only a desperate man would cling to for dear life, in fact, it was the product of years of careful development that began well before the war started. It derived from gliders, and then someone thought to add a propeller to it. It was so low-rent that it didn't even have wheels until late in development, relying instead on a dolly to take off and a fixed skid to land. This in a craft with extremely combustible and hazardous fuel that would explode if you accidentally spilled onto another form of fuel that it used.

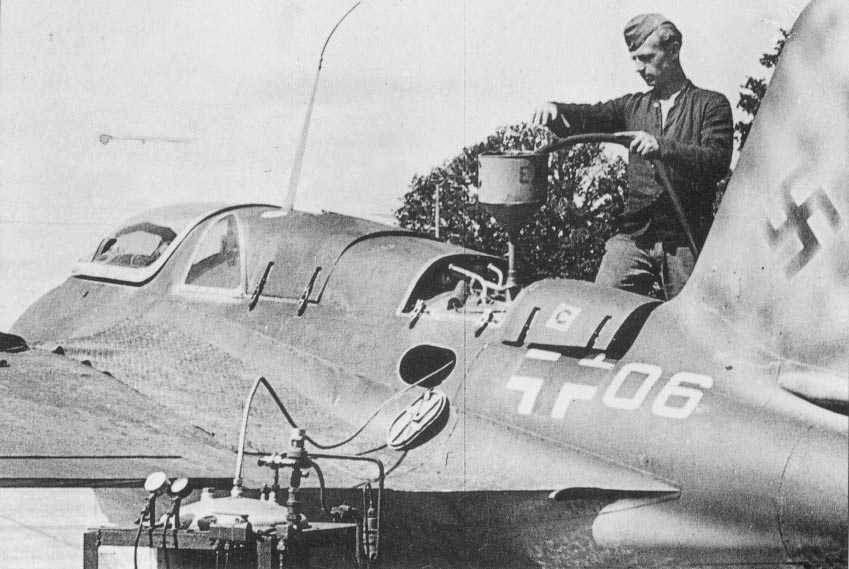

|

| Putting the C-Stuff in the C-Stuff tank. Wait, that is the C-Stoff tank, right? I better go check. |

The airframe was considered so good that a rocket engine was fitted to it as soon as one became available. The engine worked on two separate fuels that had to be kept apart and supplied to different fuel tanks: C-Stoff (hydrazine/methanol-based fuel) and T-Stoff (hydrogen peroxide oxidizer). While exceedingly dangerous, the Stoff exploded when it mixed and produced a powerful explosion that propelled the ship forward. The speed and rate of climb was unheard of, as was the peril to the pilot if the craft had a rough takeoff or landing and the tanks leaked (which happened a lot).

|

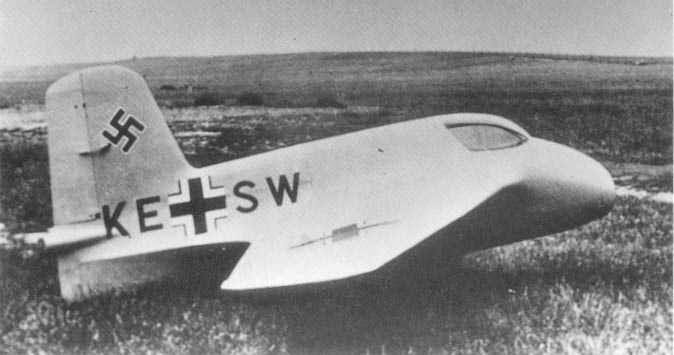

| Me 163s were small little birds. That is an advantage when people are shooting back at you. |

The crazy thing was flying as early as October 2, 1941, when test pilot Heini Dittmar flew 624.2 mph in the Komet, coming darn close to the speed of sound. Naturally, he couldn't publicize the record, but it wasn't broken (except by another ME-163) until 1947 (by some calculations, 1953). The dolly and skid were causing all sorts of problems, and the craft had to be brought off the runway by a Scheuch-Schlepper (no, I'm not making this up). It was all a big hassle and made worse by the fact that the airframe design was

too good: the slightest breeze would make the craft overshoot the runway during the unpowered landing.

|

| Taking a rest on the most advanced aircraft in the world. |

However, speed is speed, and there is no substitute. The ME 163 was the fastest thing on earth, and that counts for something in air forces. The designers worked on the problems and tinkered with different engines, and this took all sorts of time. Other problems arose: the thing was just too darn fast. When you are flying 500 mph and your target is flying 200 mph, it's just hard to aim a gun at it. Also, the flight time was incredibly short due to the small size of the craft, and the tiny ship was unstable. Finally, the plane flew high but the cabin was unpressurized, putting pressure on the pilot to stay conscious. The project was handed off from one manufacturer to another, as Messerschmidt was busy making aircraft that were actually ready for action. While it was designed by the Messerschmidt team, Junkers actually built them.

|

| A ME-163 sitting on the grass. |

Nobody seemed in a great hurry to get the extremely volatile fighter into service. Finally, some were ready in May 1944 and zipped around in the bomber stream. They put on quite a show for the Allied pilots, who watched in astonishment as the little planes zoomed by them without doing them any harm - too fast to aim the guns. Units were planned to protect key oil refineries, but ironically there wasn't enough fuel for the fighters. The program sputtered along, but nobody was really into it, and finally, in the last days of the Third Reich it was abandoned altogether. All told, the ME 163 pilots shot down some 16 Allied planes for all the effort. There are said to be ten ME 163s in museums and quite possibly some more in private hands, and there are a few well-known reproductions that fly at air shows.

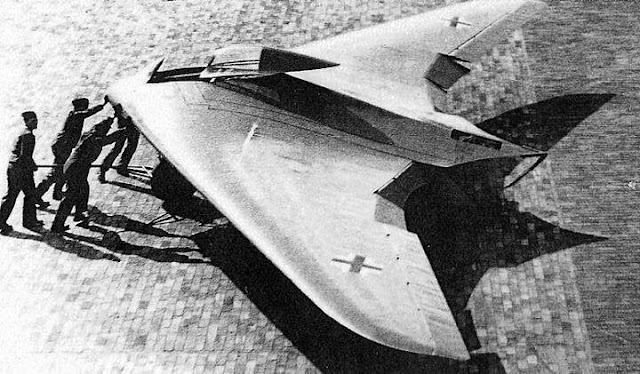

Horten Flying Wing

In the 1980s, the cutting-edge of aviation technology was stealth aircraft (and remains so today). However, the Germans got there first... in 1945.

The Horten brothers, Walter and Reimar, were glider designers. Gliders were all that Germany legally could design under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, and the Horten Brothers had fun designing alternative designs for their gliders. They joined the Hitler Youth in 1933 and continued their glider experiments.

|

| The Horten brothers in their Luftwaffe uniforms. |

Both brothers became Luftwaffe pilots, but they retained their interest in design. They were looked upon as interlopers by the real aircraft designers but had the advantage over others of being actual Party members. They were good pilots: Walter flew as Adolf Galland's wingman and was credited with seven kills.

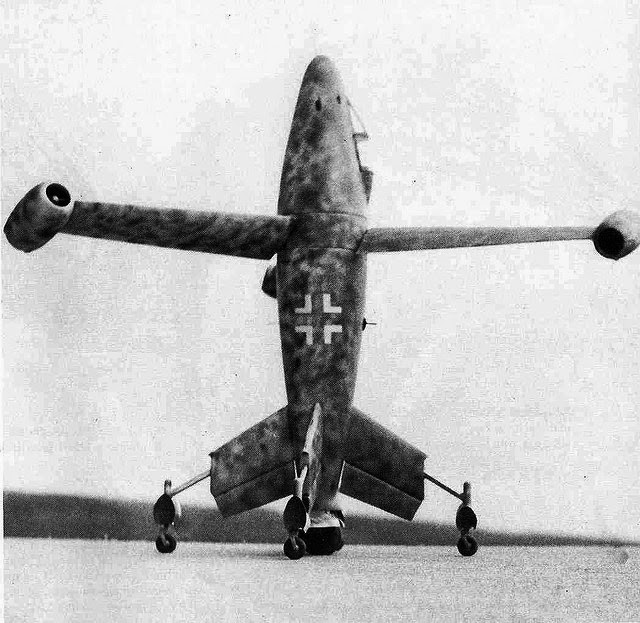

The brothers' best design was the Horten 229. It was a jet-powered flying wing that was built and flew before the end of the war. The brothers came up with other advanced designs as well, but they were never built except as gliders. They also participated in the Amerika Bomber project.

|

| I like how someone just casually parked their bike within feet of the most advanced plane in the world. |

The war ended before any of their projects could see combat. Out of anything that flew during World War II, this was perhaps the one whose basic design principles resonated the longest down through history and, indeed, remain embodied in present-day military aircraft.

|

| Horten 2-29 - WW2 German Stealth plane. A group of experts from Northrop Grumman, a global security company, recently re-built the Horten 2-29 for a television special airing on the National Geographic Channel. |

Captain Brown also

was asked (minute 7:50) about the Horten Brothers' flying wing, which came along too late to see combat.

"What's your opinion on the Germans' flying wing design, the Horten 9? Do you think they would have made a good plane?"

"Oh yes, I believe the Horten brothers, who were specialists in tail-less aircraft or all-wing aircraft - it's a difficult formula to get right, but when you get it right, it pays huge dividends, and the Horten 9 they had certainly I think got it right. And the great pity is that although we captured one which could have been repaired and it went to the United States, it was never brought to fruition. We know it has flown, it flew about four times, but not with what I call an experienced test pilot, but I had great faith in the Horten brothers."

Flying a plane like the Horten 9 took extreme bravery for anyone.

|

| The Horten plane did fly, several times. |

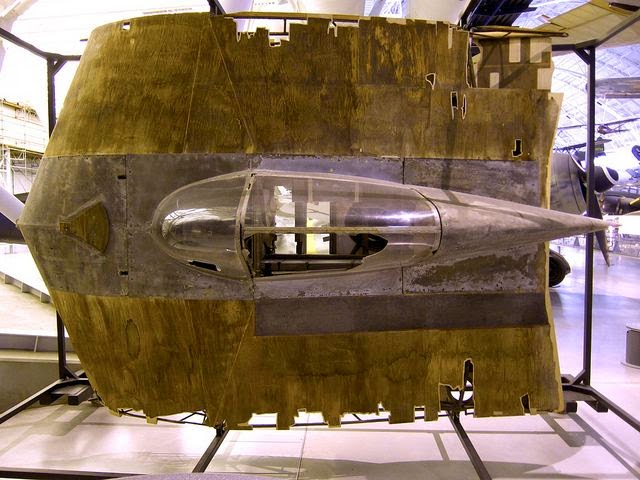

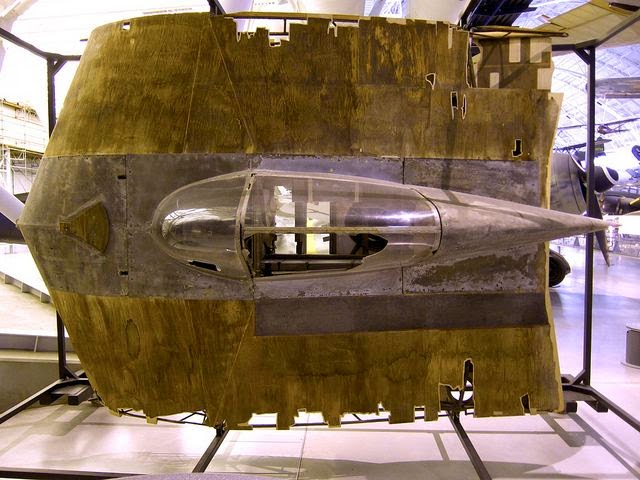

The Horten 229 (or 9, as some call it) was not a fantasy aircraft; it was built and flown several times in test flights. It had a very low frontal profile and was made of wood, so it had a minimal radar signature.

|

| The Smithsonian Air and Space Museum finally has been doing some work on the Horten, which had been sitting in crates for 70 years. Conservator Lauren Horelick and treatment specialist Matt Nazzaro study the interior beneath an access panel they have just removed from the Horten H IX V3. Note the skin removed around the air intake feeding the starboard engine. |

Recent tests of full-size replicas made according to the original designs assigning it a 20% smaller blip on a standard radar screen than its size otherwise would indicate.

|

| That is just the very tip of the nose, the plane was much larger. |

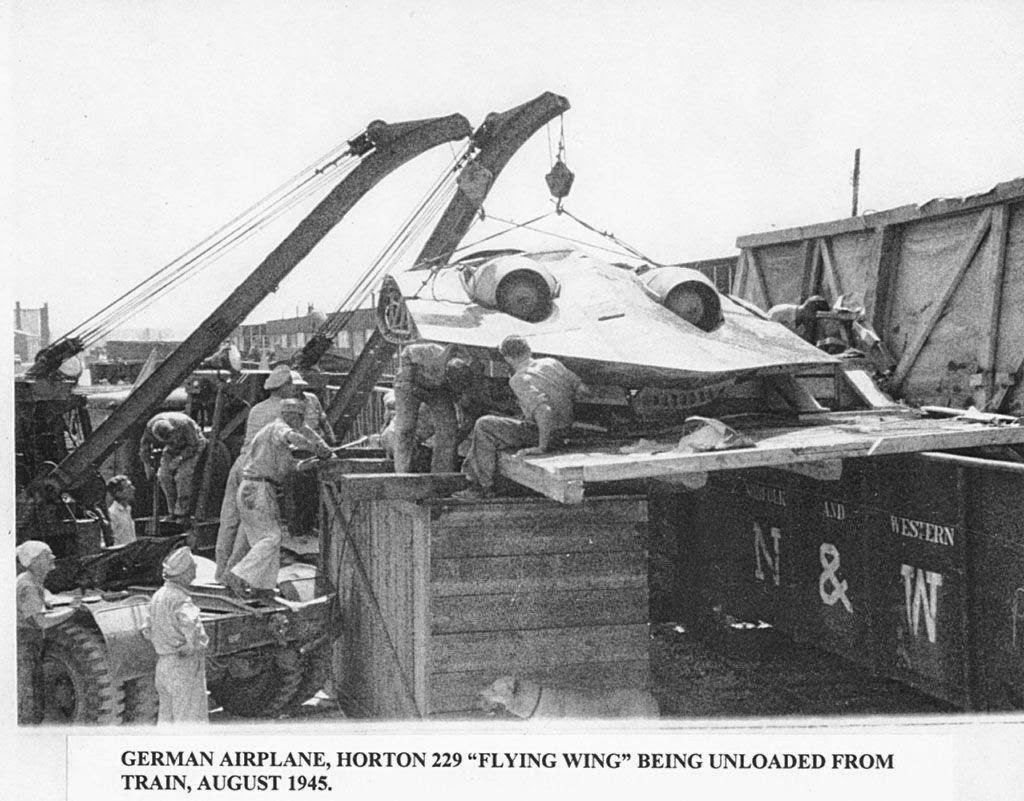

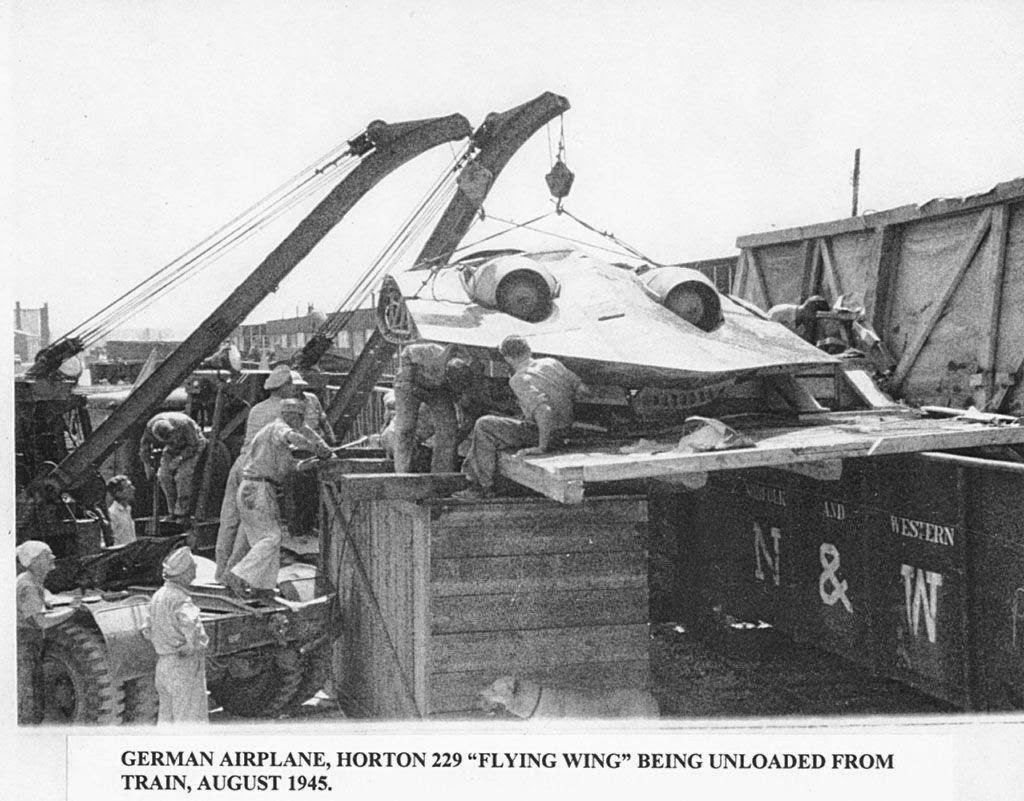

No Horten remained intact after the war, only fragments. However, some of the fragments were substantial enough to warrant bringing back to the US for further study.

|

| The Horten Ho 229 V3 being unloaded in 1945 at Freeman Field. Much of the damage to the wing roots can be attributed to the sharp angle of the hoisting strap digging into the plywood. |

The Germans typically did not want their equipment captured intact. It was a point of serious pride, especially within the Luftwaffe.

|

| What remains of the Horten Ho IX / Horten Ho 229 Jet-Powered Flying Wing at the Smithsonian. |

Only the small central section was salvaged from a forgotten hangar. The Germans destroyed the wings themselves before its capture.

|

| The Horten parts remain in a storage shed to this day. |

The Smithsonian Museum has the only surviving Horten 229, but it was locked away in storage and never restored until recent attempts.

JU-390 "New York Bomber"

|

| Actual JU-390 being readied for flight. |

Adolf Hitler badly wanted to bomb New York City. The Luftwaffe also had a prime target on the US mainland: the major automotive plants in Michigan that were churning out airplanes that were wreaking havoc on the German homeland. The generic name for development in this area was the "Amerika Bomber." Both objectives were within reach by war's end, but territorial losses and industrial damage prevented these ambitious objectives from being realized.

The Luftwaffe had halted development of strategic bombers in the 1930s - "The Fuhrer does not ask me how big my bombers are, only how many I have," Hermann Goering once said - a decision which the Germans regretted as the years passed and the Allies demonstrated the devastating power of four-engine bombers. Some projects were attempted, but it was tough to tool up and develop a capable strategic bomber. One project that did advance beyond the design stage was the "New York Bomber."

The German designers took the Junkers 290 and expanded it, lengthening the wings to fit a total of six engines and lengthening the fuselage to increase the payload. It would have carried a crew of ten in full operational mode, with two 13mm machine guns in a gondola, two on the beam as in Allied bombers, and a 20 mm cannon in the tail. The plan was to prepare it for maritime reconnaissance, bombing, and transport. The engines were BMW 801D radial piston engines of 1730 horsepower apiece. These would have provided a top speed of 314 mph, better than Allied bombers and comparable to most fighters of the day, with a range of 6,030 miles and a service ceiling of 19700 feet.

|

| JU-390 in flight. |

Two prototypes were built and flown. The first flight was October 20, 1943, with the second prototype also flying that month. Tests continued through mid-1944. There is an unproven legend that one of them flew for 32 hours and came within sight of New York City that spring before turning back to its field in France - possibly within the aircraft's capability, but highly unlikely and fiercely denied by some experts. Other, more exotic legends such as that one actually flew over Detroit and New York are pretty much impossible.

If the war had continued, the JU-390 would have had major strategic implications. The impact would not have been the bomb damage caused by the craft but from the Allied response. The Americans were notorious for taking careful security precautions against proven threats, for instance instituting extensive convoys and other defensive measures in response to the short-lived U-Boat operation in 1942 off the American coast (Operation Paukenschlag). If even a few of the "New York Bombers" had bombed continental US targets, the US would undoubtedly have instituted costly air patrols, perhaps put up observation and barrage balloons off the coast, and instituted naval surveillance for air attacks. This would have cost the US greatly and diverted resources from other pressing tasks. It never happened, though, with the JU-390 project basically abandoned when the Allies captured the French airfields in August 1944. The planes were flown to Germany and destroyed.

It is theoretically possible that Hitler (or others) could have flown this bomber somewhere far away as the Reich collapsed. However, where would he have gone? There were no safe havens, and this plane was very noticeable.

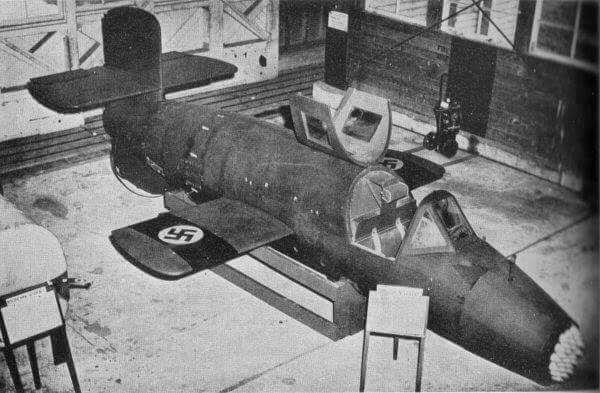

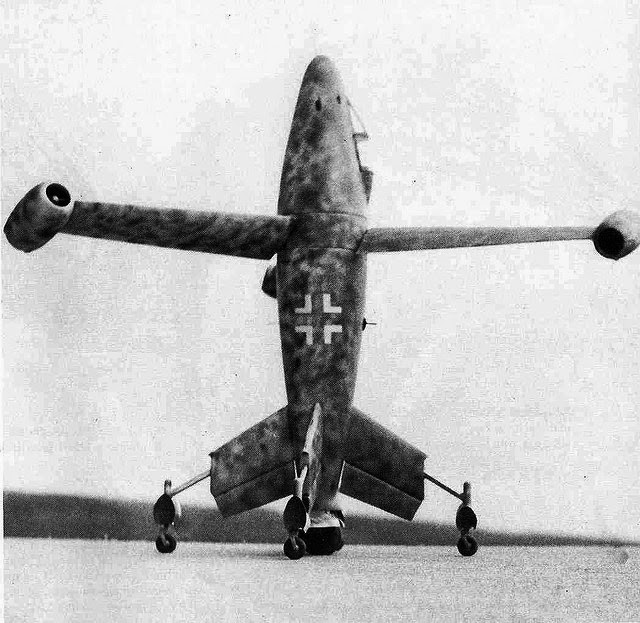

Henschel HS 132

|

| Henschel Hs 132. |

The Henschel Hs 132 was a World War II dive bomber and interceptor aircraft of the German Luftwaffe that never saw service. The unorthodox design featured a top-mounted BMW 003 jet engine (identical in terms of make and position to the powerplant used by the Heinkel He 162) and the pilot in a prone position.

Luftwaffe Helicopters

In February 1938, the world's first helicopter was demonstrated by the German test pilot Hanna Reitsch indoors at the Deutschlandhalle sports stadium in Berlin, Germany. Called the Focke Wulf Fw 61, it subsequently set several records for altitude, speed and flight duration culminating, in June 1938, with an altitude record of 3,427 m (11,243 ft) and a straight line flight record of 230 km (143 mi).

|

| FW 61, of the type flown by Hanna Reitsch. |

The first production series helicopter was the Flettner Fl-282.

|

| Flettner Fl-282. |

The German Navy was very interested in the Flettner Fl-282. Many landings were staged on the German cruiser Köln. The Siemens-Halske Sh 14 radial engine of 150-160 hp was very reliable and only required servicing every 400 hours.

Another Luftwaffe helicopter was the Focke Achgelis FA 223. It was armed with a 1 x 7.92 mm MG15. It had a crew of two and was substantially larger than the other early types, though it came into service in 1942, around the same time as the Fl-282.

|

| Focke Achgelis FA 223. |

Famed German Hanna Reitsch recalled the first public demonstration of a helicopter, made in order to evade media bias against German aviation, in 1938:

The Americans also had some experimental helicopters in the works, but the Germans were far ahead in this area. Only a couple dozen Luftwaffe helicopters were made because the Allies bombed the main production facility, and those that were made were used primarily as artillery spotters, operating out of the test field at Rangsdorf. If the Germans had had better luck, the order the Wehrmacht placed for 1000 of them would have been filled and they would have been everywhere.

Luftwaffe helicopters were not even that rare, they just didn't have a defined role yet, such as helicopters gained during the Vietnam War as troop carriers. They may look sketchy because they don't look like later helicopters, but they were capable of lifting cannons and even airplanes.

Below is some rare footage of Luftwaffe helicopters of World War II, set to "Where Eagles Dare," the theme to a 1968 Clint Eastwood film:

Several Fl-282 survive, one in Russian hands, one with the Americans at Dayton, and one with the British in Coventry.

Dornier DO 335 Pfeil (Arrow)

|

| Dornier DO 335. |

The Dornier Do 335 Pfeil (Arrow) was a heavy fighter. It was

big and had two engines, one mounted fore, the other aft, and both on the plane's center-line. The German designers were extremely conscious of air resistance and went to great lengths to try to minimize it. This unique push-pull layout actually worked and gave the Arrow a speed unmatched by any other piston-driven aircraft. Only a few saw any kind of operational service, but they were just over the horizon.

|

| Dornier DO 335. |

The Arrow was only spotted by the Allies now and then in the last days of the war, most likely on training flights gone wrong. During April 1945, there simply wasn't anywhere left to train that wasn't an operational area. However, when you are spotted by enemy planes and fired upon, that's combat, even if you merely run away faster than your pursuers can catch you (which the Arrow did).

|

| Do-335s on the apron at Oberpfaffenhofen at the war's end, including unfinished two-seat versions. |

Armament was two 15 mm Mk 103 machine guns in the nose and a 30 mm Mk 103 cannon firing through the propeller hub. Some versions also had cannon in the wings, too. Top speed was well over 400 mph, 474 mph with a boost. Having the two propellers in-line helped reduce wind drag and gave the design greater speed than, say, an American P-38.

Below is some footage of the DO 335.

This is one aircraft that was being manufactured at war's end and would have seen major combat duty later in 1945 if the war had lasted that long.

Heinkel He-162 "Salamander"

While another of the last-minute jet projects undertaken by the Germans as the Allies closed in, the Heinkel He-162 "Salamander" was no jury-rigged disaster. The Germans had the technology, the materials and, most importantly, the desperate need to crank out a capable jet fighter, and the ME-262 couldn't do it alone. Envisaged as a "People's Fighter" which could be flown by just about anyone, the Salamander instead was a high-performance cutting-edge piece of hardware that stood a good chance of turning the tide of the air war if the Wehrmacht had been able to hold its airfields.

|

| The He-162 Salamander, basically a jet engine with a vestigial plane attached. |

The Allies were flattening German cities one by one, and the Luftwaffe had to do something. Hitler was interfering in the ME-262, diverting its development to make it capable of bombing, and its jet engines were troublesome and in short supply. What was needed was a less complicated project that could be slapped together without any rigamarole and put in the hands of Hitler Youth who would destroy the enemy bombers as they had destroyed the British tankers at Caen. Air defense was becoming critical because the Allies were destroying the life's blood of any modern army, the Reich's oil supplies.

|

| Heinkel HE162 jet in British markings. |

Luftwaffe head Hermann Goering and Albert Speer, the armaments chief who knew what the failing industrial base could still achieve, came up with the idea of a "throwaway fighter," one made out of wood and other non-critical materials. Specifications were issued on September 10, 1944, after France had fallen and the Russians were on the Vistula but during a stable period on all fronts. Heinkel already had designs in the works - all aircraft designers have contingency designs ready to be worked up in short order - and won the contract. It cranked out the prototype in the incredibly short time of six weeks, reflecting the extreme desperation being felt by higher-ups who probably shot anyone who delayed development.

|

| A surviving He 162. |

The first Salamander flight on December 6, 1944, succeeded, but the second flight a few days later killed the pilot and revealed glue problems that had to be worked around. Small changes were made to compensate for the structural problems without correcting them, which never would have been attempted in normal times. The changes continued to be plagued with problems throughout its short lifespan. Still, that the craft could be produced at all under conditions in Germany during late 1944 was little short of a miracle.

|

| A captured He-162. From conception in September 1944 to operations in early 1945 - an incredible industrial achievement using slave labor and all exigencies of a police state. |

Production proceeded immediately despite the problems - there was a war on! I./JG 1 had the honor of training in the brand new fighter at Parchim, which was a convenient 80 km south-southwest of the Heinkel factory. The Allies were on to the German plans and promptly bombed Parchim, sending the unit scrambling to other airfields, winding up near the Danish border. There simply wasn't enough time to get the unit ready in a normal fashion, but in desperation, some of the planes were flown on missions during the last month of the war anyway - the pilots knew it was a death-trap, but the survival of their country was at stake. Some kills were achieved - how many will never be known, but there were several - at the cost of about the same number of planes lost primarily to mechanical problems. Armament was two 20mm MG 151 cannon, while top speed was variable depending on height but reached a maximum of an incredible 562 mph for short durations at 20,000 feet. It was the fastest jet in existence, though the rocket-powered ME-163 was faster. The flight duration was a measly 30 minutes, which caused some fatalities as pilots couldn't make it back to the runway.

|

| The captured He 162 in British markings. |

Rather than destroying their surviving aircraft at the surrender as many other units were doing, JG 1 kept the advanced fighters intact and turned them over to the Allies. Testing showed that they were fine, responsive aircraft with issues that, properly developed, could have been devastating weapons. Of all the last-minute projects of the Luftwaffe, the little-known Salamander may have held the most real promise, but time had run out. Several examples survive.

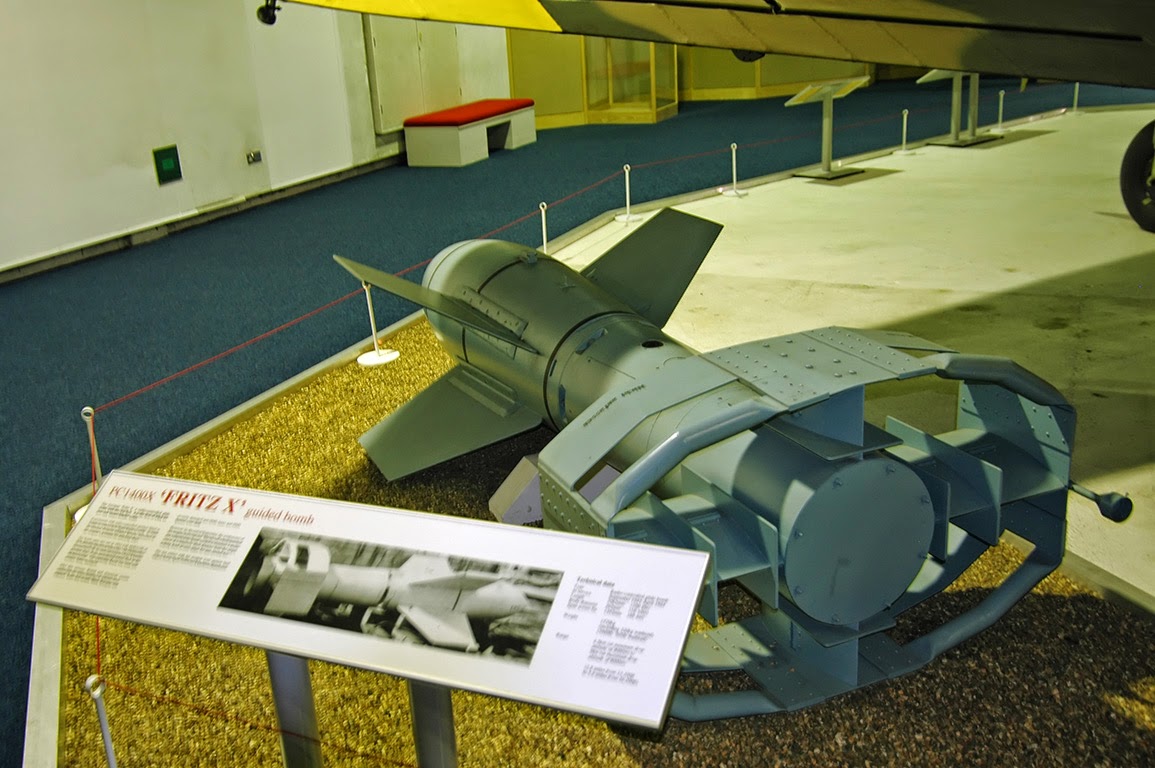

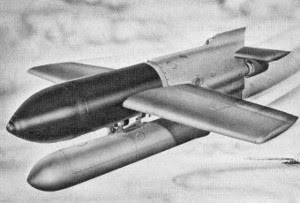

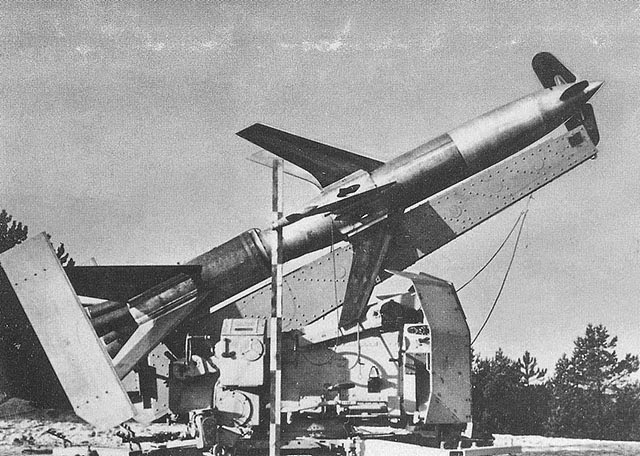

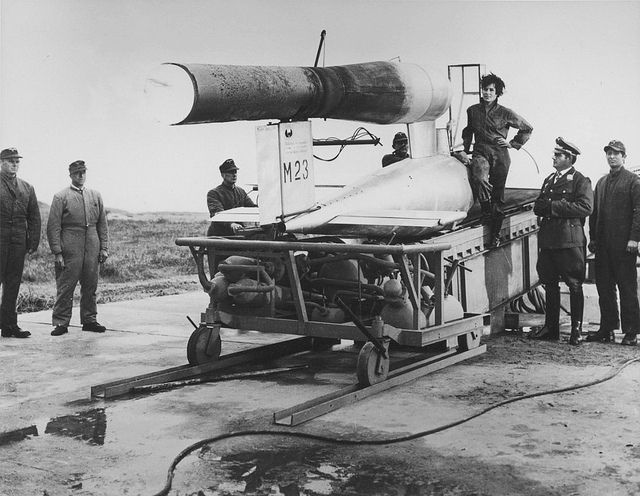

Fritz X

Guided missiles are so common now that they seem as though they always have been around, sort of like the term "teenager." But the word "teenager" was only invented in the mid-1940s, and so was the guided missile - and the Germans did it. There was a concurrent American program, the Azon, but as usual with these advanced designs (and these are issues of national pride, but the truth will out) the Azon came along later and is completely forgotten, while the German Fritz X was used first and to stupendous effect.

Nobody is trying to claim that the Germans were better people for having created these weapons first. However, trying to claim the reverse - that they didn't create some epic things first - is simply anti-intellectual. Which is great if you aren't interested in the truth, but we try to describe only the truth here. It is important to be exact about what actually happened during World War II, because once you head off into fantasyland you get Holocaust deniers and all that. The Holocaust happened, and so did the Fritz X.

The training ground of the Spanish Civil War had proven the difficulty of hitting moving ships with bombs - a lesson it took the Allies a long time to learn. A German engineer, Max Kramer, started thinking about the problem, and he experimented with small 250 kg bombs, adding remote-controlled spoilers in the late 1930s. Much like modern video games, the controls on the bomb were activated with a joystick via radio signal. The transmitter was a Funkgerät (FuG 203) Kehl, the receiver a Funkgerät (FuG 230) Straßburg. The transmitter had a range of only five miles, and the controlling aircraft had to remain in steady flight, exposing it to counter-fire.

|

| Do 217K-2 with its unique “non-stepped” cockpit. This photo is from September 1943 (Federal Archive). |

Gruppe III of Kampfgeschwader 100 Wiking (Viking), designated III./KG 100, was supplied with the Fritz X. The medium-range Dornier Do 217K-2 was chosen as the control aircraft, though at times other aircraft such as the "flying fireworks" Heinkel He 177A Greif long-range bomber may have used them. Everything was ready by July 1943, which offered some perfect opportunities for deployment because that was when the Allies were exposing themselves by first invading Sicily, then the Italian mainland. There were numerous protected Luftwaffe bases in Italy from which to operate, and the Allied fleet had minimal (at least compared to later) air protection. Conditions were ripe for a demonstration of the Fritz X's capabilities.

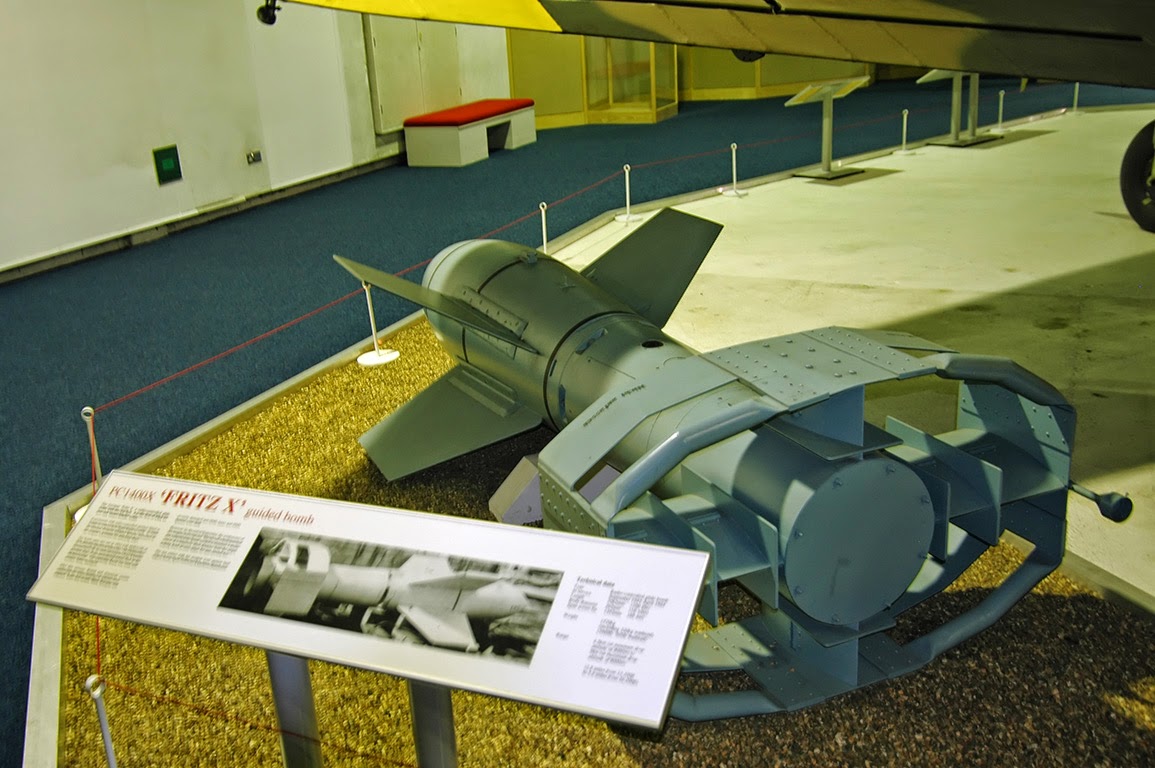

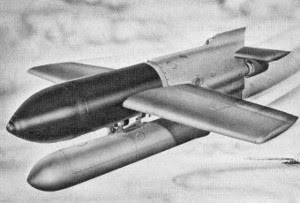

|

| The Fritz X. |

Attacks began on July 21, 1943, with no effect, and continued sporadically through August. While there were no successes, the attacks gave the crews invaluable experience. By September, they were fully up to speed. The Italians switched sides in early September, and this truly ticked off the Germans, who were afraid of the example on their other numerous shaky allies. Order must be maintained, they knew, so something had to be done to punish Italy. Hitler's standard response then and later was to launch an air raid on the offender to little effect, but this time there was a better target.

|

| The Roma meets its fate. |

The Italian fleet had done nothing useful throughout the war except provide some air defense to scattered Italian cities, at least as the Germans saw it. In fact, the Italians had huge fuel stocks saved up that astonished the Germans when they found them after the Italian change of sides. This is fuel that could have supported numerous high-value missions when they might have achieved strategic results. There thus was no love lost between the Germans and the Italian Navy after the latter defected. After having not contributed at all to the war effort, the Italian battleships promptly broke out of their northern Italian harbors and fled for the Allies on September 9.

|

| Fritz heads for the Roma (artist's conception). |

However, it was a typical screwed-up operation, with the Italian fleet uncertain what to do and where to go to surrender, having neglected to figure out before leaving the harbor where they were supposed to go. The bottom line is that they remained in Italian waters too long, in daylight, where the Luftwaffe had clear supremacy, and paid the price. The pride of the Italian fleet was the Roma, their newest and best battleship. As it dithered, the Germans sent their Dorniers after it. The first attack failed, but the second succeeded. The Germans sank the Roma with two hits and a near miss. Over 1200 men (figures vary, but it was somewhere around 1250), including the commanding Admiral, died. The Roma's sister ship, the Italia, also was hit but limped into Malta. The Italia made no further contribution to the war effort.

|

| Fritz X on display. |

Other successes followed. The secret Allied trump card with its successful invasions was the overwhelming naval gunfire support that protected the invasion beaches. Salerno, the invasion of Italy proper, provided another fine area for use of the Fritz X. The USS Savannah, a cruiser, was hit and sent home on September 11, 1943, lucky to have survived. The light cruiser HMS Uganda was next, hit by a Fritz-X off Salerno at 1440 on 13 September 1943. It also barely survived and was put out of action. Some merchant ships may have been next, though accounts vary. The British battleship Warspite, though, was a definite casualty on September 16, 1943, and also sent home, never to be the same again. A few other ships were damaged. The Salerno invasion by then had succeeded and the Allies were heading north, so the attacks were discontinued.

|

| Loading a Fritz X. |

The Allies then proved their incredible ability to mitigate the effect of dangerous opposing weapons. They captured an intact Fritz X system and used it to develop jamming counter-measures. These worked, and the Germans did not have the time, the ability or the opportunity to pierce them sufficiently to make the Fritz X significant again. The system's main flaw wasn't the weapon itself, but the fact that it required some kind of control of the surrounding airspace for it to take effect. By 1944, the Allies had complete control of the sky, and while the Fritz X may have been used on D-Day, by then the launching platform - the Dorniers - couldn't get anywhere near their targets, much less launch the missiles and fly unmolested while guiding them to their targets. After that, the Germans had much bigger problems to worry about and the Luftwaffe was in terminal decline. But as a revolutionary weapon, the Fritz X had made its mark.

Henschel Hs 293

|

| Henschel HS 293 Radio-controlled Glide Bomb. |

A variant was the Henschel HS 293 Radio-controlled Glide Bomb, which was rocket-propelled and guided by a gunner in the launching aircraft by radio. While a much more sophisticated and impressive weapon, the radio bomb was known to only sink one ship, the corvette HMS Egret (and possibly another whose attacker is disputed with the Fritz). The Allies figured out how to jam the radio frequency used to guide the Hs 293 (the Allies were extremely sensitive to German radio-guiding practices due to their experience with the Knickebein system and successors during the Battle of Britain). Sometimes, simpler really is better. Apparently, there were several different variants on this general idea.

Henschel Hs 117

|

| A Henschel Hs 117 Schmetterling on display at the National Air & Space Museum (NASM), Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. |

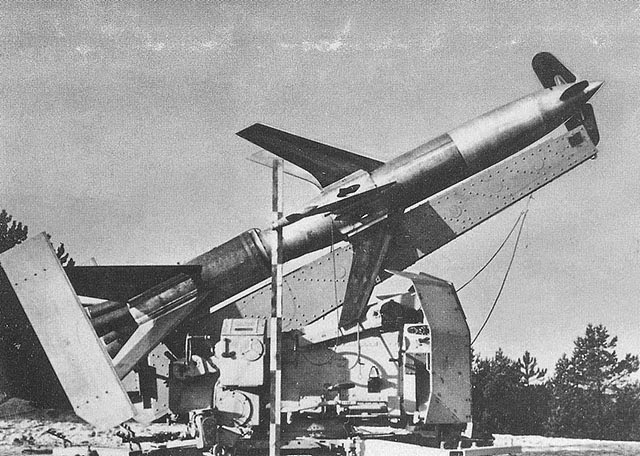

The Henschel Hs-117 Schmetterling ("Butterfly") was the work of Professor Herbert A. Wagner, who also developed the Henschel Hs 293 anti-ship missile. It was an extremely sophisticated design, intended to be used as a TV guided German surface-to-air missile. It would be guided to the target using a telescopic sight and a joystick to guide the missile by radio control. Beginning in May 1944, the Luftwaffe tested this Hs-117 design extensively, but Wagner couldn't get it quite right. He couldn't even figure out how to launch it, via plane (Heinkel He 111, this version was designated Hs 117H) or from a 37mm gun carriage. Despite a majority of test flights failing, the desperate German government slotted the missile into mass production in December 1944. This may have been more for public relations purposes than any hope that the HS 117 actually would work, as late-war rumors about "wonder weapons" was thought to help German morale.

|

| Henschel Hs-117 Schmetterling ready to fire. |

The project simply was not ready for use despite the order to mass-produce it. SS-Obergruppenführer Hans Kammler canceled the Hs-117 project in February 1945. The Hs-117 is another of those "if they only had another year" weapons. Or two years. Or maybe five.

|

| The Ruhrstahl X-4. |

The Ruhrstahl X-4 was a wire-guided air-to-air Luftwaffe missile. The X-4 was the basis for the development of later ground-launched anti-tank missiles, including the Malkara missile. The X-4 did not see operational service.

Rheintochter

|

| Rheintochter. |

The Rheintochter was a German surface-to-air missile developed during World War II by Rheinmetall-Börsig. Its name comes from the mythical Rheintöchter (Rhinemaidens) of Richard Wagner's opera series Der Ring des Nibelungen. The Heer (army), which bizarrely was in charge of all rocket development and not the Luftwaffe (rockets were considered a form of artillery), ordered it in November 1942. However, regardless of classification, in spirit, if not, in fact, this was a Luftwaffe project.

The missile was a multi-stage solid fuelled rocket. There were 82 test-firings, with an air-to-air version contemplated. A typical rushed late-war desperation project, it never succeeded. The project was canceled on February 6, 1945. Given a few more years of ordinary development, it probably would have been the best anti-aircraft missile of its time, but it needed time that Germany no longer had.

V-1 flying bomb

The V-1 flying bomb (German: Vergeltungswaffe), also known to the Allies as the buzz bomb, or doodlebug, and in Germany as Kirschkern (cherrystone) or Maikäfer (May bug), was an early pulse-jet-powered cruise missile used by Germany against the Western Allies.

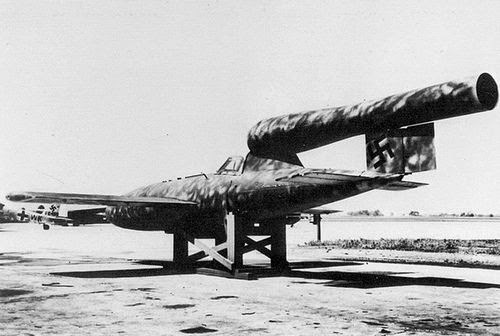

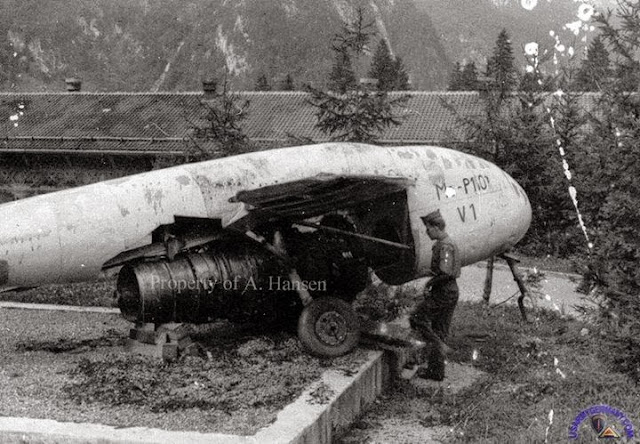

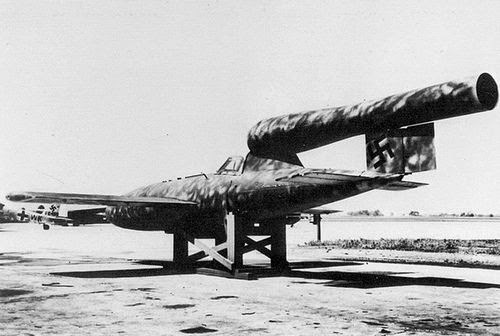

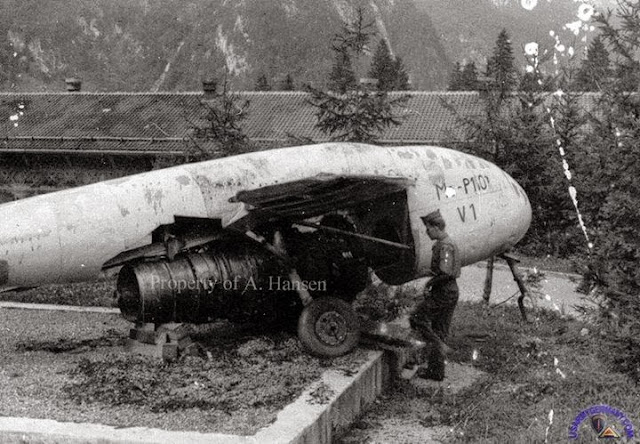

|

| A V-1 preserved in a museum in Auckland, NZ - The War Memorial Museum (author's photo). |

The V-1 was another of the many German advanced weapons that appeared during the final years of the war. It didn't have a category - it was simply known at the time as a flying bomb - until the 1980s when the term "cruise missile" was invented. That's how far ahead the Germans were.

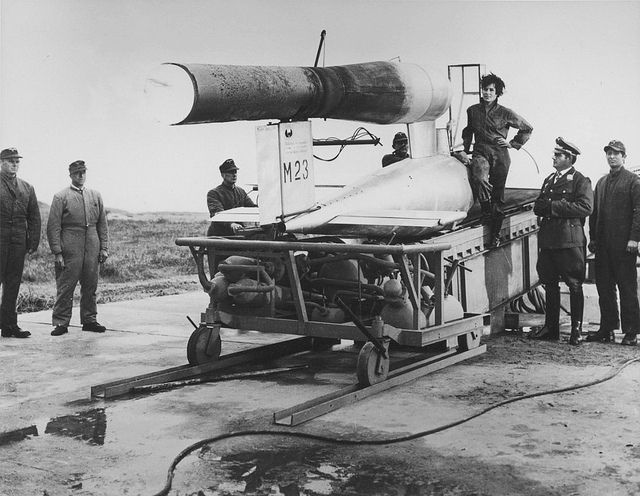

The V-1 was developed at Peenemünde Army Research Centre on the Baltic coast by the German Luftwaffe under the leadership of Werhner von Braun. The concept originated in the 1920s, with the pioneering rocketry work of Dr. Robert Goddard and Hermann Oberth. It combined two elements that were not banned as research by Germany. While military aircraft were banned under the Treaty of Versailles, that was not the case for rockets or gliders. So, the underlying technology could be developed freely within Germany and not furtively in the Netherlands or Soviet Union as was done with Luftwaffe airplane projects. Engineer Fritz Gosslau began work on pilotless aircraft in 1936 for Argus Motoren, an auto/plane engine manufacturer. In 1939, the company submitted a proposal to the RLM (German Air Ministry) headed by Hermann Goering to create a pilotless weapon carrying a 2200 pound warhead up to 310 miles. Once the RLM accepted, Argus formed a consortium with Lorentz AG and Arado Flugzeugwerke to develop the missile.

The RLM got cold feet. It was canceling or downgrading in priority futuristic projects in the 1940-1941 time frame due to over-confidence about the war situation and a desire to focus on proven designs. Ernst Udet, Luftwaffe Director-General of Equipment who showed a lot of practical sense about designs, canceled the project. However, Gosslau persevered on his own. After Udet's suicide in November 1941, and after a bit more development and the war situation a bit less rosy, Udet's replacement Generalfeldmarschall Erhard Milch reinstated the project (now called Fi 103) in mid-1942 with Fieseler the chief contractor. Not only did Milch re-start the program, but he also made it a top priority. Things had changed that much in a year.

|

| V1 over London in its death dive. |

The first V-1 flight took place on December 10, 1942, dropped from an aircraft. Development continued, and the V-1 was more or less ready by mid-1944. It launched from fixed skids, with the engine set to cut off after flying a certain time/distance. It then would drop to the ground and explode. The skids were built in France along the Channel coast, pointed at London. After the Allied invasion on D-Day, June 6, 1944, the Germans rushed the V-1 into action, and the first salvo took place a week later, on June 13, 1944.

|

| A V-1 on the launch ramp. These would be launched from wooded areas due to Allied air attacks. Apparently. the Germans weren't worried about the fire hazard. |

Between June and October 1944, when the last launching site was over-run by the Allies, 9,521 in total, sometimes 100 in a day. This was the "Little Blitz" that was continued on by the V-2 until the end of the war. Residents of London learned that a V-1 in flight was no big deal, but when the engine cut off, it was time to run for cover. The V-1 was the most effective of all of the Luftwaffe super-weapons, causing about as much damage as the entire original Blitz all by itself. The British suffered over 22,000 casualties. After it no longer could be used against London, attacks were directed at the main Allied port, Rotterdam, and other important targets.

|

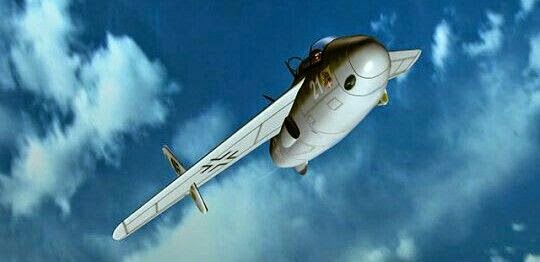

| A V-1 in flight - what a chasing interceptor would have seen. |

The Allies were forced to spend heavily on counter-measures, which is what made the V-1 such a cost-effective weapon. With an average speed of 350 mph, the V-1 could only be caught by the most advanced Allied planes.

|

| Fi-103 manned V-1. |

The Germans developed a late-war manned version of the V-1, but it was never used.

|

| The Fieseler Fi 103R, code-named Reichenberg, was a late-World War II German manned version of the V-1 flying bomb (more correctly known as the Fieseler Fi 103) produced for attacks in which the pilot was likely to be killed, or at best to parachute down at the attack site. They were to be carried out by the "Leonidas Squadron", Group V of the Luftwaffe's Kampfgeschwader 200. Nothing came of it. |

This experimental aircraft featured in a dramatic opening to a 1965 World War II film, 'Operation Crossbow,' about bombing the secret rocket factories. In the film, Hanna Reitsch pilots one and figures out why it hasn't been working, suggesting corrective action. The scene actually isn't that far from the truth.

|

| German pilot Hanna Reitsch sitting on a V-1 rocket manned version (Fieseler Fi 103R) on the test site Rechlin (Rechlin-Larz). 1944 Germany. Yes, it existed, and yes, she would have flown it in a heartbeat if Hitler asked. |

It made for good drama, and Reitsch certainly was capable of such stunts, but the Germans were not, despite what people might think, too keen on suicide missions. Besides, that was an awful lot of work to put into an aircraft for only one flight, when a Me-262 could be constructed instead and be used over and over. The key problem is that the Germans never developed a warhead that would justify these one-way missions on a cost basis.

|

| The Fieseler Fi 103R. |

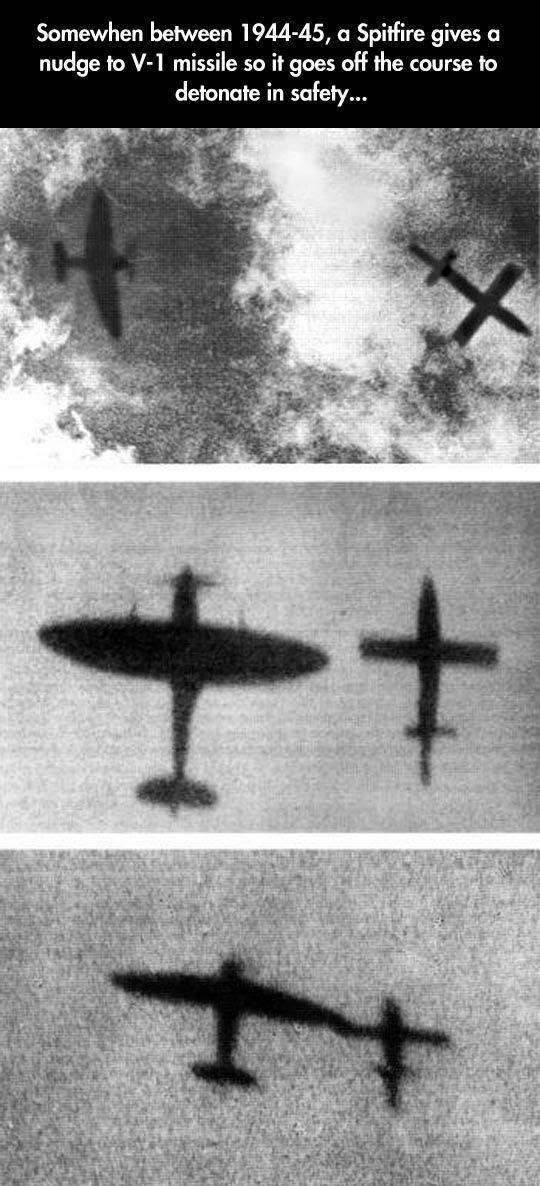

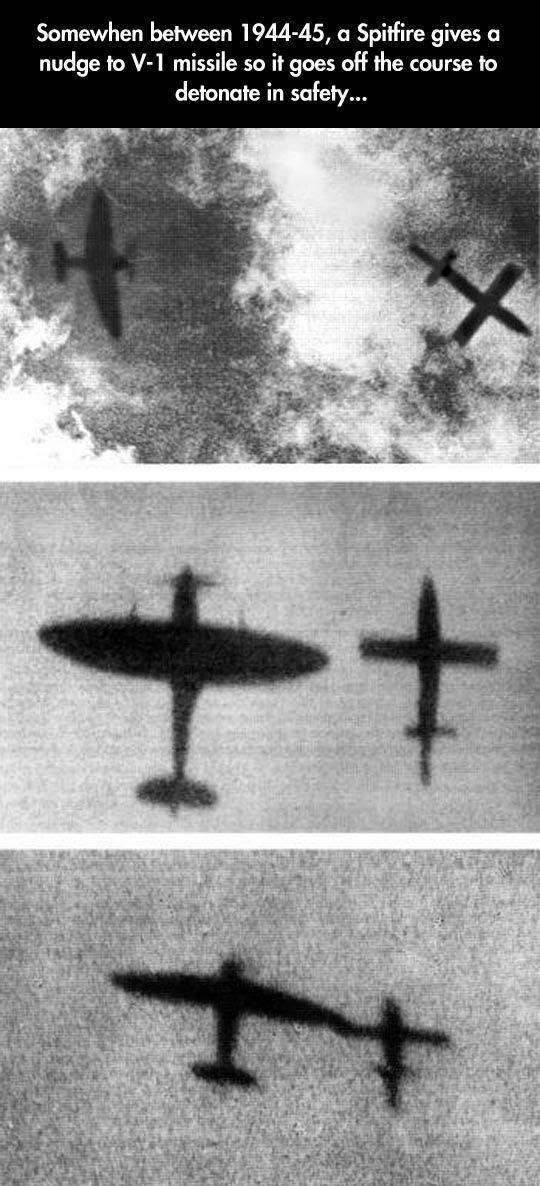

The fast Hawker Tempest, of which very few were available, were used to defend against the V-1s, as were Mosquito bombers and jet-powered Gloster Meteors. As shown below, even Spitfires could sneak up on a V-1 and nudge it off course.

|

| FZG 76 Piloted V-1 rocket. Allied code name, Doodle Bug. |

The Allied counter-measures worked to a certain extent and were greatly hyped to put the worrying citizenry at ease (much like with the Patriot missile several decades later), but many, many V-1s got through and caused the Allies a lot of difficulties. Again, the problem was the lack of suitable warhead, some TNT or similar explosive wasn't going to be a game-changer by that point.

|

| An RAF fighter (apparently a Spitfire) intercepting a V-1. |

Much is made of the Allied jets and how they were just as capable as German jets. The Germans, however, were a generation ahead and that is why the Allied jets never saw action during the war. The Meteors, in fact, only became truly useful after redesigns and new versions became available after the war. The V-1s, though, caused a lot of damage during the war, were effective, and, from the German perspective, were a useful and cost-effective weapon to have in the arsenal.

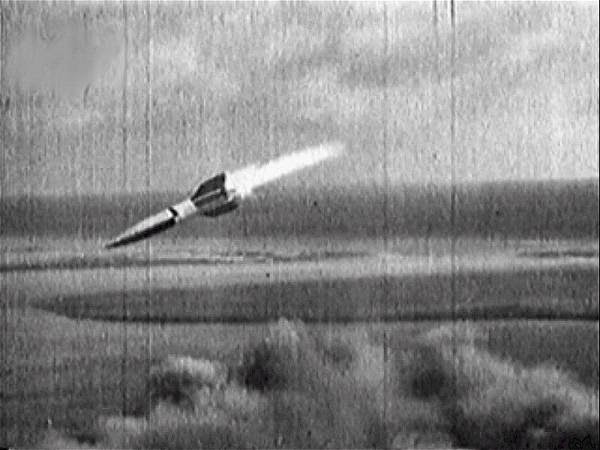

V-2 rocket

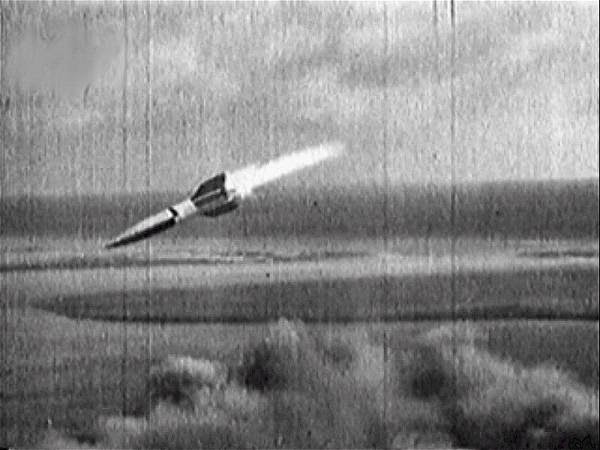

The V-2 (German: Vergeltungswaffe 2, "Vengeance Weapon 2"), technical name Aggregat-4 (A4), was the first long-range ballistic missile, and the first one used in combat. It was the product of decades of development and a high-point in technological development during World War II. The V-2 led directly to missile development by the Allied powers in subsequent decades and the first Moon landings in 1969-1973.

|

| This was a completely mobile missile, which could be pulled out of hiding, raised and launched literally in minutes. |

Hermann Oberth was an Austro-Hungarian Transylvanian who developed an early fascination with rockets after reading Jules Verne's book, "From the Earth to the Moon." He began idly designing and building rockets as a young student, then during World War II began experiments on his own with rockets that used liquid propellants. Nobody was very interested, but he continued his studies after the war, and published in book form a school dissertation he had written, "

Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (The Rocket into Interplanetary Spaces).

Wernher von Braun also had an interest in rockets. He bought a copy of the self-published Oberth book and matriculated at the Technical University of Berlin, where he assisted Oberth in liquid-fueled rocket motor tests. Artillery Captain Walter Dornberger noticed von Braun's promise and arranged an Ordnance Department research grant for von Braun. Von Braun then worked next to Dornberger's existing solid-fuel rocket test site at Kummersdorf testing field, and he wrote a doctoral thesis ("Construction, Theoretical, and Experimental Solution to the Problem of the Liquid Propellant Rocket" (dated 16 April 1934))that spelled out advanced concepts for rocketry. He and the others also borrowed from the advances of American physicist Robert H. Goddard and even occasionally contacted him with questions. It was an ideal team: Oberth the theorist, von Braun the implementer, Dornberger running interference with the authorities and providing resources.

|

| The distinctive checkerboard paint pattern was later sometimes replaced with olive green |

The group worked on rocketry throughout the 1930s. Walter Thiel designed an engine that solved many technical problems and became the basis of the A-4. Dornberger arranged a move of the group to the Army Research Center at Peenemünde, the top-secret research, design, and manufacturing facility on a small Baltic island just off the German coast. The top leadership was not too impressed - Hitler correctly assessed the A-4 at that stage as nothing but a long-range artillery shell - but Dornberger kept the project going. As the fortunes of war turned against the Germans, they began looking for panacea projects, and the V-2 leaped to the top of the list.

After a decade of development, von Braun announced during September 1943 that the rocket was "practically complete/ concluded." Indeed, from a long-term perspective, it was, but the Devil is in the details. It took another year of frantic work to iron out the bugs. Hitler now changed his tune and, whatever his actual thoughts about the rocket's actual effect on the war, knew a propaganda tool when he saw one. He commanded that assembly line production of the V-2 begin at the Mittelwerk site by prisoners from Mittelbau-Dora, a concentration camp where an estimated 20,000 prisoners died during the war. The glorious V-2 was put together by horribly maltreated people who were working on the tools of their own suppression.

|

| A V-2 flying straight and true. |

The first launch in combat was not against England, but against Paris on September 8, 1944; Hitler always attacked capitals that had defected, and this was his classic gesture of contempt. Attacks against London began the same day. Unlike the V-1, the V-2 could be launched from anywhere from mobile launchers, so the Allied conquest of France did not prevent the rocket's use against London. Londoners began dying, and the public did not know why: the rockets arrived unseen and unheard until they exploded.

The Allies took various countermeasures of minimal impact, but the only true solution was to overrun the underground German production facilities and strangle the manufacturing inputs. As with everything else, the inability to defend had pluses and minuses: on the plus side for the Germans, that meant the rockets got through. On the minus side for Germany, it meant the Allies did not have to spend exorbitant amounts on aircraft defense, as they did on, say, patrols against U-boats or air attacks and naval positioning against the Tirpitz sitting endlessly at anchor in Norway. The V-1 was a much more effective weapon in this sense, though not as terrifying.

Over 3100 rockets were fired, and most of them were

not against London. Only 1402 were against England, 1358 against London. The rest were against European targets: 1664 against Belgium (Antwerp being a key Allied port), 76 against France, 19 against The Netherlands, 11 against the Remagen Bridge after it was taken intact in early March 1945 (to no effect whatsoever).

|

| A V-2 nearing the end of its flight. |

The warhead was 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) of Amatol, a typical World War II explosive mixture of TNT and ammonium nitrate. With a better payload, the rocket might have had a strategic impact on the course of the war, but ultimately the V-2 was nothing but a painful sideshow - painful for both sides. In fact, sometimes the Germans didn't even bother with an explosive payload at all, as the rocket's impact itself had an overwhelming destructive effect. Poison gas was available and could have been used to great effect, but then the Allies would have started dropping it on German cities. Besides, Hitler had an aversion to poison gas from his World War I days.

There were 2,754 civilian deaths in London alone attributed to the rocket before operations ceased on March 27, 1945, 1,736 killed in Antwerp. V-2s left a huge impact crater and caused extensive - but random - damage. The V-2s almost always were aimed against cities because they fell wherever they fell, anywhere within a huge radius, unguided (though radio guidance was attempted with middling results). They were as likely to fall uselessly in an empty field or in water as on a crowded cinema full of people (as happened once in Antwerp, killing over 500 people in a stroke).

The cost to Germany was fantastically expensive. It was the German "Manhattan Project," and in fact cost more than the US development of the atomic bomb. SS General Hans Kammler organized production using slave labor, thousands of whom died due to maltreatment, without which costs would have been even greater. Overall, for the cost, the rocket hurt Germany more than it hurt the Allies, though it hurt both sides a great deal. It did, however, allow Hitler and his cronies to keep the troops fighting a hopeless war for months based on the spurious propaganda promise that the V-2 was just one of many "super weapons" coming along that would lead Germany to ultimate victory despite all the obvious evidence to the contrary. That was perhaps the largest cost of all.

|

| A Saturn V liftoff. Note the black/white pattern. Remind you of anything above? |

However, this was one weapon that also had a future civilian use of great import. The money the Germans spent was not wasted. Scientists such as von Braun were brought to the United States under Operation Paperclip and continued their research in New Mexico, using captured V-2 rockets (but this time without slave labor). That was just the start. Von Braun personally advised President Kennedy, who accordingly made his bold promise to go to the Moon during the 1960s. Von Braun, Oberth and the rest helped make it happen, along with countless American scientists. The Russians also used German technology. They captured some German scientists and used them for their own space/missile program (they likely would claim it was all their own doing), and may have spied on the American program's progress as well. As a character in "Ice Station Zebra" commented, "The Russians put our camera made by *our* German scientists and your film made by *your* German scientists into their satellite made by *their* German scientists."

Space flight is a peculiar legacy of the Third Reich, but spaceflight would have happened decades later than it actually did without the Germans' contributions to basic space science.

Feuerlilie

When casually dismissing German attempts at technological breakthroughs that might change the entire war situation around as mere fantasy, armchair historians sometimes forget the sheer number of projects under development from early in the war that may, under the right circumstances, have borne fruit. Jet aircraft, missiles, helicopters - everything seemed right on the verge of fulfillment.

|

| Rheinmetall-Borsig F55 Feuerlilie anti-aircraft missile, 1943. |

The Feuerlilie (English, "Fire Lilly") was one such project. The Aviation Research organization (Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Luftfahrt - DFL) recognized as early as 1940 the need for aerial defense beyond what fighter aircraft could deliver, showing phenomenal foresight. The DFL thus set in motion development of a surface-to-air missile, first in a 25cm diameter version which had about a handful of launches by 1943. It was a two-stage rocket that was launched from a kind of ramp.

|

| "Feuerlilie Rakete" by US Airforce - TM 9-1985-2/Air Force Technical Order TO 39B-1A-9 GERMAN EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE (Bombs, Fuzes, Rockets, Land Mines, Grenades & Igniters). Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Feuerlilie_Rakete.JPG#/media/File:Feuerlilie_Rakete.JPG |

The work developed steadily, but a good motor could not be found. As with the various jet engine projects, it wasn't until 1944 that the various technical problems began to be resolved. The final F-55 was 55cm in diameter and used Rheinmetall 109-505/515 solid rockets. There were four launches, beginning in May 1944, so the project did produce a real, flyable missile. However, the missile proved to be too unstable in flight to serve its intended purpose. Development continued into 1945, and due to the war situation, the entire project was shut down in January of that year. Given a couple of more years, the missile had the potential to be quite effective.

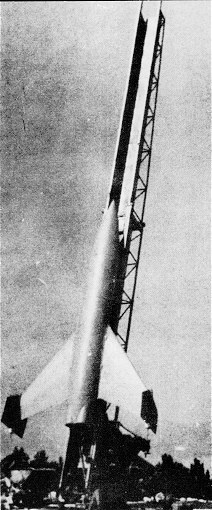

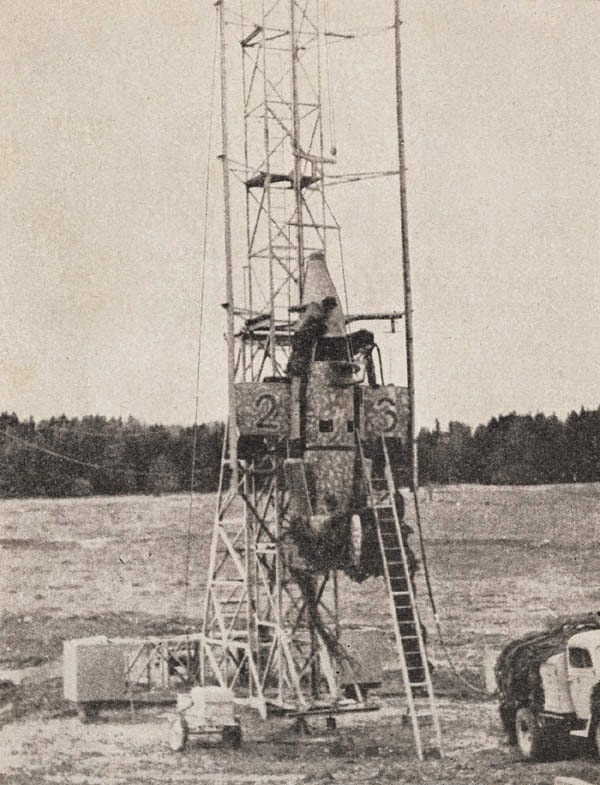

Ba 349 Natter

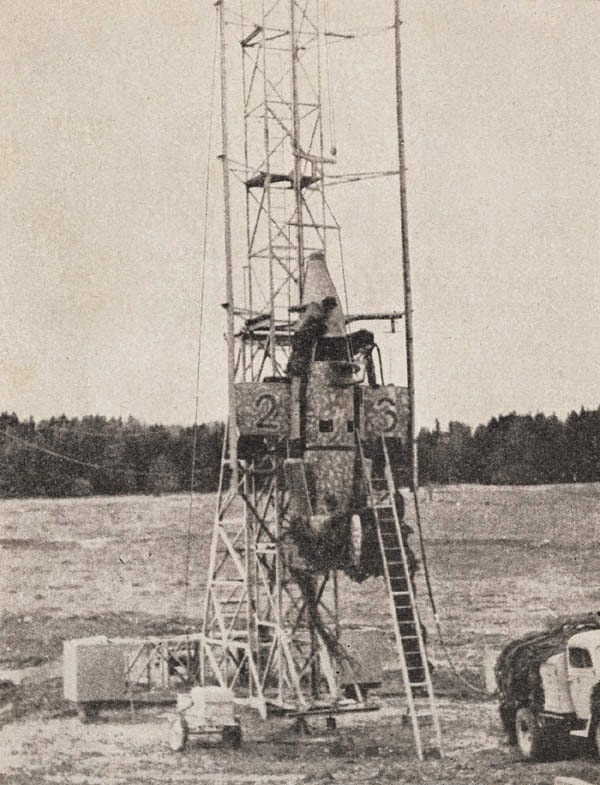

|

| Ba 349 Natter. The Ba 349 Natter actually flew, so it cannot be considered strictly as an aircraft only at the paper stage. However, its only known flight managed only to kill its pilot on 1 March 1945. The unfortunate volunteer pilot, Lothar Sieber, became the first man in history to take off from the ground in a vertical orientation under rocket power, 15 years before the major post-war powers attempted it. |

It was a typical 1945 German project born out of desperation. The objective was to fly the plane against the Allied bomber streams. This project remains shrouded in mystery. Out of all those projects, only a few were at all viable, and none made a difference. The Natter proved irrelevant to the war's outcome despite the high hopes vested in it.

The Bachem Ba 349 Natter (Viper, Adder) was a World War II German point-defense rocket-powered interceptor, which was to be used in a very similar way to a manned surface-to-air missile. After a vertical take-off, which eliminated the need for airfields, the majority of the flight to the Allied bombers was to be controlled by an autopilot. The primary mission of the relatively untrained pilot was to aim the aircraft at its target bomber stream and fire its armament of rockets.

Factory workers saw the Soviets approaching and decided to carry one example into the mountains to present to the Americans. That Ba-349 is known to survive in storage at the Smithsonian Institute in Suitland, Maryland, but it is not on public display.

|

| This is the Bachem Ba 349 which factory workers transported into the Alps to turn over to the Americans. |

Aircraft and Related Equipment Still at the Design Stage

Below are some cutting-edge ideas that very easily could have been integrated into weapons systems by 1946 or 1947. These are all proven technology, they just had to be developed a bit further.

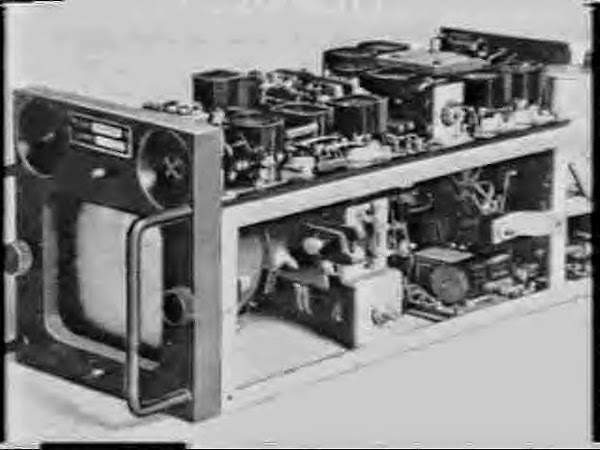

Television Remote Control

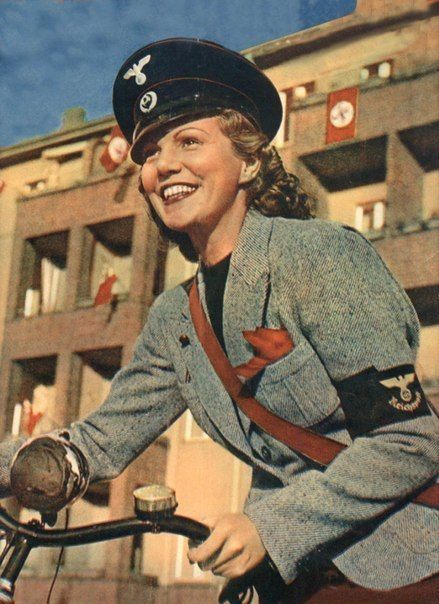

|

| German Third Reich television intended as missile remote control. |

Television was cutting edge technology during World War II, having been invented by a variety of scientists and engineers around the world over a period of about 50 years. It was used in a limited fashion in the New York City metropolitan region in the late 1930s. It also was used in Germany in the mid-1930s - in fact, the 1936 Berlin Olympics were the first Games to be broadcast on television (and not on NBC!). The Germans evidently had studied remote control using television and were busy making a television remote control system for their Mistel Bomber when the war ended.

|

| Henschel Hs 117 Schmetterling. |

The plan was to use the television guidance on the Henschel Hs 117 Schmetterling ("Butterfly") surface-to-air and air-to-air missile. In the air-to-air version, this missile would be controlled by using a joystick - just like you could use on your 1990s Microsoft pc games like Flight Simulator. The Schmetterling project was promising, and obviously, the concept was completely feasible, but neither the missile nor the guidance system was far enough along for it become operational. Despite poor testing results, in January 1945, the production of 3,000 missiles a month was proposed. However, it just wasn't ready, and on 6 February, SS-Obergruppenführer Hans Kammler canceled the project in order to focus on things that were ready. Under better circumstances, the Schmetterling with its joystick control that was decades ahead of its time might have become operational in 1946 or 1947.

Focke-Wulf Triebflügel

|

| Focke-Wulf Triebflügel. |

The Focke-Wulf Triebflügel (Triebfluegel) was one of the weirdest designs of the war that might just have worked. This was a thrust-wing fighter that was the first planned VTOL aircraft (Vertical Take-Off and Landing). It was planned to be used as a defense against the incessant Allied bomber streams flying over Germany. The best attribute of this design is that it didn't require a runway, which during the latter stages of the war were being bombed incessantly by the Allies.

There was no prototype built because the Allies captured the factory before the designers could get beyond the wind-tunnel stage. The aircraft is unique because it has neither wings nor rotors as such, and would have ascended and descended by firing the three rockets attached to the fuselage. It would have operated somewhat like a helicopter, except with the entire lower body rotating. It was projected to have four cannons in the forward fuselage.

|

| This is a rather fanciful depiction of what the Triebflugels might have looked like. |

Since it never got to the prototype stage, it is impossible to say how it would have operated or what problems it might have had. However, it is quite an unusual design that had no equal anywhere else.

Lippisch Delta Wing Fighter

Dr. Alexander Lippisch was born in Munich, Germany in 1894. He worked on Delta winged fighters during the 1930s, and his design led to the Me 163 rocket-powered interceptor which flew successfully and shot down roughly a dozen Allied bombers.

|

| The Delta jet. |

After the war, Dr. Lippisch's Delta DM-1 glider and delta jet fighter designs led directly to the Convair XF-92 and subsequently to the highly successful F-102 Delta Dagger and F-106 Delta Dart fighters of the US (which was eager to apply German delta-wing technology to the emerging jet technology of the time period). The end product by Convair became the B-58 Hustler. The public may not have known much about this design (because they weren't interested and weren't told), but post-war American aircraft designers sure did.

DM-1 data

Span

5.92 meters

Length

6.6 meters

Height

3.18 meters

Wing Area

20 sq meters

Wing Sweepback

60 deg

Weight empty

297 kg

Weight loaded

460 kg

Typical Release Altitude

8,000 meters

Speed max

560 km/h

Speed landing

72 km/

Experimental Messerschmidt Fighters P.1079

|

| P.1079. |

The Messerschmitt company was building refined versions of the Me 109 throughout the war, but it also was designing advanced aircraft propelled by pulsejets, the same propulsion as the V-1 flying bombs. This remained strictly on the drawing board - with one or two exceptions - and the entire project was canceled in December 1944.

|

| P.1070. |

|

| Messerschmitt P-1101 prototype Oberammergau, photo by Arthur Hansen, 7854 Military Intelligence Détachement. Appears to be a mockup solely for a wind-tunnel test. |

|

| ME P-1011. It appears to be a jet engine with a plane loosely attached. |

|

| Messerschmitt P-1101. |

Junkers Pulse Jets EF-126

The Junkers company also tried to develop some pulse jets that would serve as fighters. They got a frame together without an engine. The Soviets tried to build one after the war and apparently did, but then they dropped the project.

|

| EF 128 painting |

|

| EF 128 painting |

2020