Background

Cardiac tamponade is a rare cardiovascular emergency caused by abnormal fluid accumulation in the pericardial space. As the pericardial effusion develops, the increased intracardial pressure leads to compression of the cardiac chambers, impeding normal cardiac output and circulatory functions. Tamponade often occurs when the rapid rate of fluid accumulation overcomes the pericardial stretch capacity before compensatory mechanisms can be activated.1,2 Cardiac tamponade has been reported following mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination and COVID-19 infection.3–10 Globally, there have been approximately 596 million cases of COVID-19 and 6.4 million reported deaths as of July 2022. Over 12.6 billion vaccination doses have been provided over 184 countries, which averages to be 161 injections per 100 persons worldwide. As of August 24, 2022, over 360 million Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine doses and 230 million Moderna (mRNA-1273) vaccine doses have been administered in the United States.5 We present a case of hemorrhagic pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology, requiring emergent pericardiocentesis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination.

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and obesity (BMI of 38.3kg/m2) presented to the emergency room with a two-week history of sharp non-exertional substernal chest pain worsened with inspiration, shortness of breath, and fatigue that started one week after receiving the second dose of the BNT162b2 (BioNTech/Pfizer) COVID-19 vaccination. She denied palpitations, fever, cough, flu-like symptoms, weight loss, and swelling. She denied recent travels, sick contacts, and insect bites. Past medical history was significant for hypertension and obesity. Her medications included hydrochlorothiazide and carvedilol. She denied tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use. Family history was significant for coronary artery disease in her grandmother.

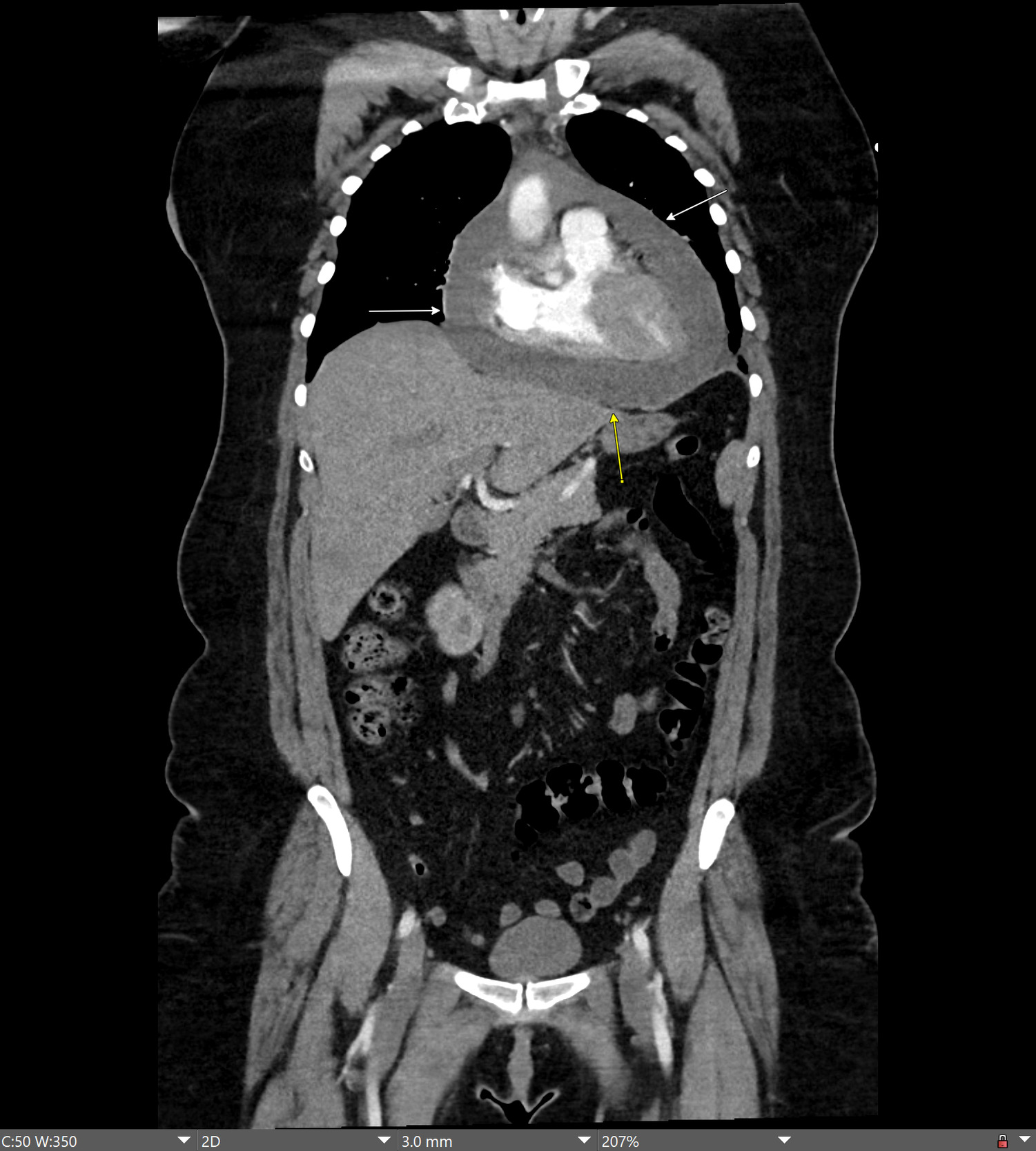

On presentation, she was afebrile, and her vital signs included an elevated blood pressure of 149/98 mmHg and tachycardia with a heart rate of 120 beats per minute. On cardiac examination, the heart sounds were clearly audible without muffling; a regular cardiac rhythm was present without rubs, murmurs or gallops. Jugular venous distention and pulsus paradoxus were absent. Complete blood count and complete metabolic panel were normal. Serial cardiac enzymes including serum troponin, brain natriuretic peptide, and SARS-CoV-2 (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) tests were normal. Antibody tests for human immunodeficiency virus, viral hepatitis, coxsackie, parvovirus, herpes simplex, Epstein Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and borreliosis were non-reactive. Serum testing for autoimmune causes of pericarditis including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and angiotensin-converting enzyme tests was unremarkable. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen with intravenous contrast revealed a large, mildly complex pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

An echocardiogram confirmed a large circumferential pericardial effusion greater than 2 cm around the right atrium. Echocardiographic evidence of cardiac tamponade physiology and impending hemodynamic collapse including significant respiratory variation in Doppler flow across the tricuspid valve, right atrial collapse and right ventricular buckling was present. The left ventricular ejection fraction was 60-65% and left ventricular size was normal. The patient was transferred to a tertiary care hospital for emergent pericardiocentesis. Five hundred twenty milliliters of bloody exudative pericardial fluid were removed, and a pericardial drain was placed and removed one day later. Pericardial fluid analysis yielded normal gram stain and acid-fast bacilli stain for tuberculosis as well as negative bacterial and fungal cultures. Cytologic examination did not identify a malignant cause.

Repeat echocardiogram revealed resolution of the pericardial effusion and tamponade physiology. The patient was treated with an anti-inflammatory regimen of ibuprofen and colchicine. She was resumed on hydrochlorothiazide and carvedilol. At a one-year follow up, her clinical outcome remained excellent without recurrence of pericarditis.

Discussion

This report describes the first reported case of a patient with pericarditis and hemorrhagic pericardial effusion with tamponade one week following second dose of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. The diagnosis of hemorrhagic pericardial effusion and tamponade was thought to be likely related to mRNA vaccination through the exclusion of other etiologies of pericarditis including infectious, autoimmune, and malignant causes. The close time of onset of pericarditis, pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade to mRNA vaccination in this case corresponds to other published reports which describe onset of pericarditis occurring most commonly within 1-2 weeks after the second dose of mRNA vaccination (Table 1).

Symptoms of cardiac tamponade include fever, pleurisy, and dyspnea. Clinical findings include elevated jugular venous pressure, muffled heart sounds, and hypotension (Beck’s triad), and pulsus paradoxus.1,2 Causes include idiopathic (viral), post-cardiac injury, uremia, autoimmune disorders, neoplastic syndromes, and tuberculosis.1–3 Cardiac tamponade occurs in 25-30% of large pericardial effusions.1,2

Pericarditis has been reported following infection with the SARS-COV-2 virus. Data from 40 health care systems in the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network found the incidence of cardiac complications (myocarditis, pericarditis) significantly higher following SARS-CoV-2 infection than after mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination across stratified gender and age groups.11 In a review, 62% of thirty-nine COVID-19 patients diagnosed with pericarditis were men with a mean age of 51.6 years.4 Common symptoms included chest pain (68%), fever (65%) and dyspnea (56%). Twenty-six patients had pericardial effusion and 12 developed tamponade.4 Thirty eight percent were treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and 53% with colchicine. One patient received anakinra (an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist) after failed colchicine therapy. Two patients died during hospitalization due to sepsis. Pericardial effusion was found more frequently in patients with severe or critical disease.4 Pathogenesis of pericarditis in COVID-19 patients is believed to be immune system dysregulation and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, similar to other cardiotropic viral infections. NSAIDs and colchicine are the mainstays of initial treatment. Corticosteroids are used as second line therapy for patients with allergy or contraindication to NSAIDs, with the caution of avoiding higher dosages due to increased recurrence risk and prolonged disease course.

Acute pericarditis is a rare, mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine-related adverse event with an overall incidence of 3.26 per 1,000,000 administered doses. Goddard et al. conducted a medical records study in an integrated health care delivery system, revealing 41 cases of pericarditis following five million doses of mRNA vaccination.3 Symptoms included chest pain (100%), dyspnea (18%), palpitations (16%). Most cases were mild, and symptoms resolved after a short hospital stay. Patients tended to be older (31.5 years) than those with myocarditis (21.5 years). The highest incidence of pericarditis was in the 0-7 days post vaccination versus 22-42 days post vaccination, which agrees with Vaccine Safety Datalink data. Treatment with NSAIDs and colchicine are also mainstays of therapy with more favorable outcome versus pericarditis associated with COVID-19 infection.3

Two prior cases of hemorrhagic pericardial effusion associated with mRNA COVID-19 vaccination are reported, without tamponade.6,7 A 74-year-old man with a history of alcoholic cirrhosis and hypertension without COVID-19 exposure or other preceding illness, presented with fever, chills, chest pain, and back pain two weeks following second dose of BNT162b2 (BioNTech/Pfizer) vaccine.6 Pericardiocentesis and drainage were performed with 560 cc of bloody fluid. The patient recovered with ibuprofen and colchicine.6 A second case of hemorrhagic pericardial effusion was reported in a 64-year-old man with chest pain and dyspnea one week following second dose of the Moderna (mRNA-1273) COVID-19 vaccination.7 The patient’s symptoms resolved with pericardiocentesis and colchicine. The differential diagnosis of hemorrhagic pericardial effusion overlaps with serous pericardial effusions, including post-pericardiotomy complications, aortic dissection, uremia, myocardial infarction, trauma, and tuberculosis. Hemorrhagic pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade has also been described as the presentation for COVID-19 infection.7 Mehmood et al. describe a case of hemorrhagic pericardial effusion leading to cardiac tamponade as the initial presentation of lung cancer.12

Pericarditis associated mRNA vaccinations may be linked to immunogenic, autoimmune, and hormonal pathways. Despite nucleoside modifications in mRNA vaccine development, immune response to mRNA may induce an anomalous innate and acquired immune response, triggering cardiac pro-inflammatory cascades and dysregulated cytokine proliferation.13,14 Molecular mimicry may occur as select antibodies directed to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein may react against structurally similar myocardial α-myosin, that may then elicit dysregulated inflammatory responses. Higher incidence of pericarditis after vaccination in males, suggests potential differences in hormonal signaling. In males, testosterone may inhibit anti-inflammatory cells while in females, estrogen inhibits pro-inflammatory T cells and cell-mediated immune responses.13,14

Conclusion

Pericarditis and pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade are rare complications following COVID-19 infection and mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination. Patients presenting with pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea within weeks of mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination should be evaluated for possible pericarditis and pericardial effusion. Further studies are necessary to assess the potential relationship between pericarditis and mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding was obtained for this manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission. All the authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript, per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria of authorship.

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

Final approval of the version to be published; AND

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Maria Del Castillo, MD for review of the manuscript and Karolina Lickunas for editorial review and manuscript drafting.

Corresponding Author

Hien Nguyen, MD

6104 Old Branch Avenue

Temple Hills, MD, 20746

Telephone 301-702-6100

Fax 301-702-6367

Email: Hien.X.Nguyen@kp.org