Abstract

Objective

Foreign direct investment (FDI) to China has motivated increased labor migration to export processing zones (EPZs). Work environments with high occupational stress, such as production line jobs typical in EPZs, have been associated with adverse mental health symptoms.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey that examined occupational stress and symptoms of poor mental health was implemented among Chinese women factory workers in three electronic factories in the Tianjin Economic-Technological Development Area. Symptoms of mental health measured in the survey were hopelessness, depression, not feeling useful or needed, and trouble concentrating. Crude and adjusted prevalence odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated with logistic regression.

Results

Responses were collected from 696 women factory workers. Participants were aged 18–56 years (mean 28 ± 5.8), 66% of whom were married and 25% of whom were migrants. Nearly 50% of participants reported at least one symptom of poor mental health. After adjusting for covariates associated with each outcome in the bivariate analysis, high job strain was associated with hopelessness (OR 2.68, 95% CI 1.58, 4.56), not feeling useful (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.22, 3.43), and feeling depressed (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.16, 2.72).

Conclusion

This study expands on the international body of research on the well-being of women working in the global supply chain and provides evidence on the associations between occupational stressors, migration, and social support on symptoms of poor mental health among women workers. Future research to better understand and improve psychological health and to prevent suicide among workers in China’s factories is critical to improve the health of China’s labor force.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past 4 decades, China has experienced exponential economic growth (Garnaut et al. 2018). While this growth has provided improved economic gains for the country, the benefits for China’s rural population are mixed (Garnaut et al. 2018). Foreign direct investment (FDI) to China has motivated increased rural-to-urban cyclic labor migration to export processing zones (EPZs) (Garnaut et al. 2018). Young rural migrant workers are considered a vulnerable group (Zhong et al. 2018; Li et al. 2020; Wang and Tang 2020), their healthcare needs are often underserved in their urban workplaces, and their rural communities are underequipped to address these needs, leaving women migrants with minimal recourse for healthcare access (Hou et al. 2015; Li 2017; Liu et al. 2020). This study, which was conducted in response to documented suicides in Foxconn factories in China (Ngai and Chan 2012), remains relevant today (Che et al. 2020) and provides new insights into factors associated with symptoms of poor mental health among women working in factories in Tianjin China.

Many foreign electronic companies in China are located within EPZs and more than 10 million people are employed in the Chinese electronic industry, which accounts for 7.3% of the total Chinese labor supply (Han et al. 2008). Oftentimes, Chinese migrant workers in EPZs are employed in low-level positions in factories characterized by shift work, night work, and long hours of 9–15 h a day 6–7 days a week (Wang 2020; Leung 2021). More than half of Chinese migrant laborers are women and their occupational health has been historically neglected (Sun et al. 2012; Cirera and Lakshman 2017). While FDI has been found generally to improve health in low- and middle-income countries, there is a slight worsening of health when investment is in the secondary (i.e., manufacturing) sector (Burns et al. 2017). In a recent systematic review of the mental health of young workers, overtime, low autonomy, job insecurity, and low job control were factors associated with poor mental health (Law et al. 2020). Furthermore, concerns have arisen regarding the potential adverse mental health impacts of employment in EPZs. A Chinese study investigating 6711 employees of 13 enterprises found that front-line supply chain workers had the highest risk for depressive symptoms compared with other types of employees (Gu et al. 2015). Another study of migrants showed that 34% of rural-to-urban migrant workers in China exhibited common mental health problems (Zhong et al. 2018). Also, it has been reported that more than 75% of Chinese electronic employees had at least slight depressive symptoms, higher than observed in other occupational populations (Yang et al. 2018).

Due to global competition and rapid technological innovation (Kim et al. 2014), supply line workers face high job demands that may negatively affect their mental health (Zhang et al. 2017). The high burden of adverse mental health outcomes among factory workers may be due to their high workloads and the repetitive nature of their work (Zhang et al. 2017). Work environments with high occupational stress, such as in manufacturing jobs typical in EPZs, have been associated with adverse mental health outcomes including depression and anxiety (Wang et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2017). Underlying this finding, a significant association between occupational stress, mental health, and poor quality of life has been documented (Laaksonen et al. 2006; Park et al. 2009; Mark and Smith 2012; Shanbhag and Joseph 2012; Zhu et al. 2012).

Migration itself has been shown to worsen mental health outcomes due to the disruption of social networks, social isolation, discrimination, and the stress of adapting to a new environment (Lin et al. 2011; Qiu et al. 2011; Mao and Zhao 2012; Huang et al. 2017). Additionally, women workers are more likely to have mental health challenges, more frequently exposed to discrimination, and less likely to hold management positions compared with men (Bildt and Michélsen 2002; Mou et al. 2011; He and Wong 2013; Huang et al. 2017). However, there is a dearth of evidence in the public health literature assessing mental health outcomes, migrant status, and work characteristics among women workers in the global supply chain. This study examines factors associated with symptoms of poor mental health among women working in factories in Tianjin, China, and seeks to disentangle the independent roles of migration, working conditions, and social isolation as key risk factors for poor mental health.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in three electronics factories in the Tianjin Economic Development Area, which employed predominantly women. Field work was completed in July and August, 2010 in collaboration with the Department of Occupational Health at the Tianjin Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and the Tianjin Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The methods of this survey are described in more detail elsewhere (Sznajder et al. 2014). In brief, a total of 744 women workers were approached during work breaks. Women were included in the survey if they were working at the factory, could read and write in Chinese, and were not cognitively impaired. Workers who agreed provided written consent and completed a self-administered structured questionnaire.

The survey obtained information on demographic characteristics, job characteristics, and mental health symptoms. Demographic variables included age (continuous), level of education (more or less than high school), and income level (more or less than 2001 RMB). Women were asked “In the last 12 months, have you become pregnant” with the possible response options of yes and no. Migrant status was determined by asking if the respondent held a local resident card (yes or no). Social support was estimated as over ten friends compared with ten friends or less based on the question “How many friends do you have in Tianjin now” with possible responses as 0, 1–10, 11–20, and more than 20.

Participants were asked about the average number of hours worked each day in the last month and this variable was dichotomized at the mean of 10 h. Assessment of occupational stressors included measures of job type (laborer or office), overtime in the last year (yes or no), and night work in the last year (yes or no). Perceived job insecurity was measured with the question “Sometimes people permanently lose jobs they would like to keep. How likely is it that during the next couple of years you will lose your present job with your employer?” and the responses were dichotomized as strongly agree and agree compared with strongly disagree and disagree. Job strain was assessed by a Chinese version of the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) (Karasek et al. 1998; Li et al. 2004). The composite score for the JCQ was computed according to Karasek’s job strain equation; high psychological demands low decision latitude. All questions on the JCQ had the response options of strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), agree (3), and strongly agree (4). The psychological demands’ variable (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.45) was defined as the score on the following two questions “My job requires me to work very fast”, “My job requires me to work very hard” multiplied by three and added with the sum of the scores of the following questions, “I am not asked to do an excessive amount of work”, “I have enough time to get the job done”, and “I am free from conflicting demands that others make” subtracted by 15 and multiplied by two. Decision latitude was determined by the summation of decision authority and skill discretion. Decision authority (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.41) was calculated as the sum of the following three questions “My job allows me to make a lot of decisions on my own”, “I have a lot of say about what happens on my job”, and the reverse coded variable: “On my job, I have very little freedom to decide how I do my work” multiplied by four. Skill discretion (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.65) was calculated as the summation of the responses for the following questions, “My job requires that I learn new things”, “My job requires me to be creative”, “My job requires a high level of skill”, “I get to do a variety of different things on my job”, “I have an opportunity to develop my own special abilities,” and the reverse coded variable, “My job involves a lot of repetitive work”. Study participants who fell above the sample median on job demands and below the median on decision latitude were defined as having high job strain (Karasek et al. 1998). Missing items used to construct the composite job strain score were imputed by substituting the mean for each variable when only one or two questions had missing values for that participant. A composite job strain score was coded as missing when more than two items had missing values. The respondents’ view of their own health was examined by a self-reported rating of fair or poor compared to excellent, very good, or good. Four questions drawn from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff 1977) and the Zung Depression Scale (Zung 1986) were used to assess self-reported symptoms of poor mental health: “I feel hopeful about the future”; “I feel that I am useful and needed”; “I feel depressed”; and “I have trouble keeping my mind on what I am doing”. Potential responses, “strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree”, were dichotomized for analysis as agree and disagree, with the negative response coded as one.

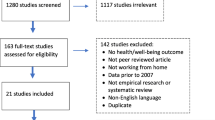

Of the 744 participants, 24 women were missing information on age and 24 women who did not complete questions on mental health symptoms were excluded, leaving 696 women eligible for this analysis. The distribution for demographic, work, and adverse mental health responses were calculated. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression models were built to examine associations between demographic and occupational characteristics and each mental health symptom. Crude and adjusted prevalence odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Independent variables associated (p value < 0.05) with each outcome variable in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression models. The significance level in the bivariate analysis was confirmed by a t test for continuous variables or a Mantel–Haenszel Chi-square for dichotomous variables at a p value < 0.05. If the prevalence of the outcome was more than 10%, the corrected risk ratio was calculated using the calculator based on the article by Zhang et al. (Clincalc.com; Zhang and Yu 1998). Analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4.

Results

The 696 participants were between 18 and 56 years of age (mean 28 ± 5.8), 25% were migrants, 67% had less than a high school education, 15% lived in a dormitory, 8% were pregnant, 72% had an income of less than 2001 yuan (~ 300USD in 2010), and 67% were laborers. Among the participants, 24% reported high job strain, 69% reported low job security, 40% reported working more than 10 h on average each day in the last month, 46% reported working at night, and 30% reported working overtime. About 36% of women in the study reported having more than ten friends. In regards to mental health symptoms, 17% reported being hopeful, 21% felt that they were not useful, 23% reported feeling depressed, and 28% reported trouble focusing. In fact, 50% of participants reported at least one symptom of poor mental health (Table 1).

In a bivariate analysis, migrants were more likely to be younger, never married, have lower education, live in a dormitory at work, earn less than 2001 RMB (about $300 USD) per month, have fewer friends, and work as a factory laborer as compared with Tianjin residents. However, Tianjin residents were more likely to report their own health was fair or poor. Frequency of reporting each mental health symptom did not differ between migrants and residents, production or office workers, high or low income, nor whether or not the participants lived in a dormitory setting. Furthermore, there was no difference in the presence of job strain or job security between migrants and residents.

The frequencies of reporting feeling depressed, hopeless, not feeling useful, trouble focusing, and reporting at least one of these mental health symptoms as well as crude and adjusted associations with participant characteristics and working conditions are presented in Tables 2–6. Feeling depressed (Table 2) was associated with working at night, working overtime, having few friends, and poor self-reported health in the bivariate analysis. In the multiple regression model, high job strain (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.03, 1.17), working overtime (RR 1.09, 95% CI 1.00, 1.16), and poor self-reported health (RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.07, 1.19) remained associated with reporting feeling depressed. For feeling hopeless (Table 3), high job strain, low job security, working more than 10 h a day on average, working at night, and reporting poor health were significantly associated in the bivariate models. In the multiple regression model, high job strain (RR 1.12, 95% CI 1.07, 1.15) and working at night (RR 1.0, 95% CI 1.01, 1.13) remained significantly associated with hopelessness. When examining not feeling useful (Table 4), older age, higher education, high job strain, low job security, working at night, having few friends, and poor self-reported health were associated with not feeling useful. In the multiple regression model, high job strain (RR 1.12, 95% CI 1.04, 1.19), low job security (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.08, 1.23), having few friends (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.03, 1.18), and poor self-reported health (RR 1.12, 95% CI 1.05, 1.19) remained independently associated with not feeling useful. When examining factors associated with trouble focusing (Table 5), in the bivariate model, having few friends was the only significant association found (RR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01, 1.17). In the final bivariate analysis, the factors significantly associated with at least one symptom of poor mental health where high job strain, low job security, few friends, and poor self-reported health were associated in the bivariate analysis (Table 6). After adjustment, having few friends (RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.16, 1.51) and poor self-reported health remained independently associated (RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.06, 1.46) with having at least one mental health symptom.

Discussion

This study advances scientific understanding of the mental health of women working in factories in China. Half of the women working in factories in the Tianjin Economic Development Area population reported at least one mental health concern, including feeling depressed, feeling hopeless, not feeling useful, or trouble focusing. Adverse working conditions, including job strain, low job security, working at night, and working overtime, were independently associated with increased risk of self-reporting a mental health concern. Self-reporting of having few friendships was also associated with increased risk for reporting mental health symptoms. The findings in this study suggest that the work itself along with social support is associated with negative mental health symptoms.

Previous research has found that the job strain of front-line employees in the electronic manufacturing industry is significantly higher than the average level of all industries in China (Zhang et al. 2016) and research has highlighted that working conditions such as strenuous job demands and perceived job insecurity are associated with unhealthy mental states (Burgard et al. 2009; Meltzer et al. 2010; Kim and von Dem Knesebeck 2016; Cho et al. 2019) with conditions exacerbated within the electronic industry (Shigemi et al. 2000; Chen et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2015). In China, factory workers are vulnerable to symptoms of poor mental health and are often exposed to unfavorable psychosocial work environments, including perceived job insecurity, low levels of job control, and high levels of job demands (Sznajder et al. 2014; Ji et al. 2016; Huang et al. 2017). The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these pre-existing negative working conditions and elevated the vulnerability of women working in the global supply chain through job loss, resulting in reduced income and increased food insecurity, concerns related to the health of themselves and their families, high levels of anxiety, and increased gender-based violence (Shields and Guevara 2020).

Results from this study found that high job strain was associated with symptoms of poor mental health including not feeling useful, feeling hopeless, and feeling depressed; perceived job insecurity was associated with not feeling useful; working overtime was associated with depression; and night work was associated with feeling hopeless. These findings are supported by studies which have found that feeling useful is an important component of job satisfaction and can modify associations between job security and depression (Takaki et al. 2010; Kumari et al. 2014). Research has also shown that when people are under high stress and have high hope, they have a problem-focused coping style; whereas those with low hope have an emotion–expression coping style. It is possible that people who work in jobs characterized by high demands and low control have fewer opportunities to problem-solve, thereby reducing capacity for hope or positive mental well-being among those workers (Steffen and Smith 2013). Night work has been shown to be associated with poor mental health in some studies (Sancini et al. 2012; Angerer et al. 2017; Sato et al. 2020). It has been hypothesized that night work interrupts the circadian rhythm, thereby disturbing natural sleep cycles and causing fatigue which would lead to poorer mental health. Occupation type or job satisfaction may modify the association between night work and poor mental health. A systematic review found that the association between poor mental health and night work was more often found in fields outside of healthcare (Angerer et al. 2017). Working overtime has been found in the previous research to be associated with depression (Kleppa et al. 2008; Virtanen et al. 2012). This association is thought to be related to the reduced opportunity for recovery time outside of work, reduced sleep, and increased negative coping behaviors (Bannai and Tamakoshi 2014; Tsuno et al. 2019). In addition to overtime, the working hours of participants in this study were long, averaging 10 h per day, which may have increased their risk for isolation and reduced their opportunities to release job stress.

Having low social support measured as ten friends or less was associated with not feeling useful and having trouble focusing. The electronic manufacturing production lines are highly repetitive and require strict discipline. This prohibits communication between workers, and can increase social isolation even during working hours and may reduce opportunities to form friendships. It is unclear why hope was not associated with social support, but it may be due to the fact that hope is future oriented (Barnett 2014; Ginevra et al. 2016). Furthermore, research has found that recovery experiences can mitigate the association between burnout and low life satisfaction (Song et al. 2021). Having more friends may allow for more recovery experiences to help protect workers from the negative effects of work stress on mental health. Bromet et al. reported that high job demands combined with a lack of social support at work increase the risk for depression and anxiety (Bromet et al. 1988). Moreover, workers often experience social isolation due to conflicting demands between family and work (Zhang et al. 2017). These demands have likely exacerbated and social connections lessened during the COVID-19 pandemic (Srivastava et al. 2021; Tang and Li 2021). Migrants who are in a new location with low support from close relatives and friends may have more difficulty coping with stress (Li and Rose 2017). However, this study did not find an independent association between migrant status and any of our measured mental health concerns, which suggests that migration is not as critical a factor as poor working conditions and social support.

Finally, poor self-reported health was associated with not feeling useful, depression, and having at least one mental health concern. This finding could be due to participant’s having an overall negative view of their health, but also could be associated with poor participant mental and/or physical health. If participants report poor overall perception of their own health, they may be less likely to be motivated to receive support to improve their mental health. This finding could support overall employee wellness programs within factories.

Hopelessness, feeling not needed or useful, and depression have all been correlated with suicide (Beck et al. 2006; Zhang and Li 2013; Whitlock et al. 2014; Xu et al. 2015; Alessi et al. 2019). Research has shown feeling needed or useful is associated with reduced suicide and improved healing following a suicide attempt (Sun and Long 2013). Suicide is a major concern among factory workers in global supply chains which have been attributed to pressure to meet quotas and work long hours, as well as low social support (Li et al. 2010; Ngai and Chan 2012; Lin et al. 2016). The findings from this study support research linking occupational strain and poor mental health. Furthermore, these findings can be interpreted within the scope of the literature on burnout. Studies have found that high job strain as measured by the JCQ is associated with burnout. Burnout has been found to be a key factor in poor mental well-being and suicide risk (Pompili et al. 2010; Xie et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2014; Koutsimani et al. 2019). Although the Chinese government has recently acknowledged that the deleterious ‘996’ work schedule (the expectation that employees work 12 h days, 6 days a week usually justified as a way to maintain the competiveness of the company) is illegal after recent work-related deaths, it is unclear whether this will result in reduced working hours or overtime compensation for factory workers (Huang 2021).

While this study has several strengths including a large sample size, diversity in jobs, and migrant status, as well as the inclusion of women from three factories, it also has a number of limitations. Since all data were self-report, it is possible that there was underreporting of negative mental health symptoms. “Cultural stoicism” in Chinese adults may result in lower responses for our mental health questions in the survey (Liao et al. 2012). Therefore, the prevalence of mental health concerns may be underrepresented in this study and our associations may be biased toward the null. Additionally, mental health may be somaticized and our respondents may not identify with the response variables listed in the survey, but complain only of physical symptoms (i.e., pain) (Lord et al. 2013). This limitation, again, could bias our results toward the null. Furthermore, due to the cross-sectional nature of this research, temporality, and therefore, causality cannot be determined. It is just as possible that migrants without mental health concerns are more likely to make friends, for example, than it is for migrants with friends to have fewer mental health concerns. Additionally, as the study population was recruited from three electronics factories in Tianjin, China, these findings may not be generalizable outside that setting. However, this study further contributes to the larger supply chain literature by providing insights from Northeast China, a historically productive region that has experienced high cyclic migration. Furthermore, important covariates were not included in our data collection instrument and are therefore missing from the analysis. Variables such as social or familial responsibilities, parity, and menopausal status could confound the results and should be included in future studies on this research question. Finally, migrants included in our study may have been healthier than the general migrant population as migrants who experience severe mental health concerns may choose to return home; therefore, selection bias in the form of the healthy migrant effect could have been present in this study. Therefore, further underestimating the prevalence of poor mental health that may have occurred in previous migration cycles and who had dropped out of the migrant labor force before data were collected for this study. Thus, the more adaptive women who had developed positive coping mechanisms and wider sources of social support are more likely to be included in this cross-sectional study.

Mental health in China contributes to large health expenditures. It has been estimated that mental disorders in China’s overall population accounted for 15% of the overall health expenditure for the country (Xu et al. 2016). Mental health was also an important concern of workers in our study with nearly half the workers showing one symptom of poor mental health. Due to cultural stoicism or somatic presentation of mental health symptoms, Chinese workers may not be likely to seek help if they struggle with poor mental well-being. A late diagnosis of depression or anxiety may cause more serious mental problems. These factors, coupled with the dearth of mental health resources for rural migrants in their home communities, and restricted access to health facilities in urban China, place migrant women workers in an untenable bind. Therefore, health programs that include Chinese cultural values such as collectivism and social identification, as well as programs that encourage and support strong social and professional networks at the factory level would likely improve the mental health of factory workers in China. This research is of critical importance as it has illustrated a high degree of mental health concerns among factory workers, illustrating the vulnerability of this population in China. The findings from this study also inform the current research across the globe as the international economy is deeply dependent on the labor of the most vulnerable and the need for improved working conditions has been even more apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic (Brown 2021; HRB and Chowdhury Center for Bangladesh studies at UC Berkeley 2021). These findings are also applicable to China’s growing footprint in the global supply chain not only as a source of manufacturing in China, but also as factory owners throughout the world, thereby potentially exporting the culture of overworked factory workers globally (Sun 2017; Brautigam et al. 2018). Greater attention to understanding the inequities and the link between working conditions and health outcomes will allow international actors and inter-governmental agencies to develop guidelines, practices, and indices to better ameliorate global inequities and structural inequalities of global supply chain dynamics. More research on the mental health of factory workers in China and across the globe is important to improving population health.

Data availability

Data and material will be provided upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Code will be made available upon reasonable request.

References

Alessi M, Szanto K, Dombrovski A (2019) Motivations for attempting suicide in mid-and late-life. Int Psychogeriatr 31(1):109

Angerer P, Schmook R, Elfantel I, Li J (2017) Night work and the risk of depression: a systematic review. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int 114(24): 404

Bannai A, Tamakoshi A (2014) The association between long working hours and health: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand J Work Environ Health 40:5–18

Barnett MD (2014) Future orientation and health among older adults: the importance of hope. Educ Gerontol 40(10):745–755

Beck AT, Brown G, Berchick RJ, Stewart BL, Steer RA (2006) Relationship between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: a replication with psychiatric outpatients. Focus 147(2):190–296

Bildt C, Michélsen H (2002) Gender differences in the effects from working conditions on mental health: a 4-year follow-up. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 75(4):252–258

Brautigam D, Xiaoyang T, Xia Y (2018) What kinds of Chinese ‘Geese’ are flying to Africa? Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. J Afr Econ 27(1):29–51

Brown GD (2021) Women garment workers face huge inequities in global supply chain factories made worse by COVID-19. New Solut: J Environ Occup Health Policy 31(2):113–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/10482911211011605

Burgard SA, Brand JE, House JS (2009) Perceived job insecurity and worker health in the United States. Soc Sci Med 1982 69(5):777–785

Burns DK, Jones AP, Goryakin Y, Suhrcke M (2017) Is foreign direct investment good for health in low and middle income countries? An instrumental variable approach. Soc Sci Med 181:74–82

Che L, Du H, Chan KW (2020) Unequal pain: a sketch of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on migrants’ employment in China. Eurasian Geogr Econ 61(4–5):448–463

Chen S-W, Wang P-C, Hsin P-L, Oates A, Sun I-W, Liu S-I (2011) Job stress models, depressive disorders and work performance of engineers in microelectronics industry. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 84(1):91–103

Cho S-S, Kim H, Lee J, Lim S, Jeong WC (2019) Combined exposure of emotional labor and job insecurity on depressive symptoms among female call-center workers: a cross-sectional study. Medicine 98(12):e14894

HRB and Chowdhury Center for Bangladesh studies at UC Berkeley (2021). The weakest link in the global supply chain: how the pandemic is affecting Bangladesh’s garment workers. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https://www.ihrb.org/focus-areas/covid-19/bangladesh-garment-workers.

Cirera X, Lakshman RW (2017) The impact of export processing zones on employment, wages and labour conditions in developing countries. Taylor and Francis

Clincalc.com. Odds ratio to risk ratio. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://clincalc.com/Stats/ConvertOR.aspx.

Garnaut R, Song L, Fang C (2018) China’s 40 years of reform and development: 1978–2018. ANU Press, UK

Ginevra MC, Pallini S, Vecchio GM, Nota L, Soresi S (2016) Future orientation and attitudes mediate career adaptability and decidedness. J Vocat Behav 95:102–110

Gu G, Yu S, Zhou W, Chen G, Wu H (2015). Depressive symptoms and influencing factors in employees from thirteen enterprises. Zhonghua lao dong wei sheng zhi ye bing za zhi= Zhonghua laodong weisheng zhiyebing zazhi= Chinese journal of industrial hygiene and occupational diseases 33(10): 738–742.

Han Y, Huo J, Shen X (2008) Electrical manufacturing services industry integrated global procurement. Manuf Autom 30(4):7–11

He X, Wong DFK (2013) A comparison of female migrant workers’ mental health in four cities in China. Int J Soc Psychiatry 59(2):114–122

Hou F, Cerulli C, Wittink MN, Caine ED, Qiu P (2015) Depression, social support and associated factors among women living in rural China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 15(1):1–9

Huang Z (2021) China spells out how excessive ‘996’ work culture is illegal. Bloomberg (August 27)

Huang W-L, Guo YL, Chen P-C, Wang J, Chu P-C (2017) Association between emotional symptoms and job demands in an Asian electronics factory. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(9):1085

Ji Y, Li S, Wang C, Wang J, Liu X (2016) Occupational stress in assembly line workers in electronics manufacturing service and related influencing factors. Zhonghua lao dong wei sheng zhi ye bing za zhi= Zhonghua laodong weisheng zhiyebing zazhi= Chinese journal of industrial hygiene and occupational diseases 34(10): 737–741

Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B (1998) The job content questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol 3(4):322–355

Kim T, von Dem Knesebeck O (2016) Perceived job insecurity, unemployment and depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 89(4):561–573

Kim M-H, Kim H, Paek D (2014) The health impacts of semiconductor production: an epidemiologic review. Int J Occup Environ Health 20(2):95–114

Kleppa E, Sanne B, Tell GS (2008) Working overtime is associated with anxiety and depression: the Hordaland health study. J Occup Environ Med 50(6):658–666

Koutsimani P, Montgomery A, Georganta K (2019) The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 10:284

Kumari G, Joshi G, Pandey K (2014) Job stress in software companies: a case study of HCL Bangalore, India. Glob J Comput Sci Technol, [S.l.] ISSN 0975-4172

Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O, Martikainen P, Lahelma E (2006) Associations of psychosocial working conditions with self-rated general health and mental health among municipal employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 79(3):205–212

Law P, Too L, Butterworth P, Witt K, Reavley N, Milner A (2020) A systematic review on the effect of work-related stressors on mental health of young workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-020-01516-7

Lee KH, Chae CH, Kim YO, Son JS, Kim J-H, Kim CW, Park HO, Lee JH, Jung YS (2015) Anxiety symptoms and occupational stress among young Korean female manufacturing workers. Ann Occup Environ Med 27(1):24

Leung E (2021) Automatic Docility in market socialism. The (Re)Making of the Chinese working class: labor activism and passivity in China. Cham ,Springer International Publishing, pp 103–129

Li J, Rose N (2017) Urban social exclusion and mental health of China’s rural-urban migrants–a review and call for research. Health Place 48:20–30

Li J, Yang W, Liu P, Xu Z, Cho S (2004) Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese (Mainland) version of the job content questionnaire: a study in university hospitals. Ind Health 42(2):260–267

Li Z, Lin Z, Fang W (2010) Study on the effect of job insecurity on emotional exhaustion: an example of Foxconn jumping incidents. 2010 International Conference on management science and engineering 17th Annual Conference Proceedings, IEEE.

Li D, Zhou Z, Shen C, Zhang J, Yang W, Nawaz R (2020) Health disparity between the older rural-to-urban migrant workers and their rural counterparts in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(3):955

Liao S-C, Chen W, Lee M-B, Lung F-W, Lai T-J, Liu C-Y, Lin C-Y, Yang M-J, Chen C-C (2012) Low prevalence of major depressive disorder in Taiwanese adults: possible explanations and implications. Psychol Med 42(6):1227–1237

Lin D, Li X, Wang B, Hong Y, Fang X, Qin X, Stanton B (2011) Discrimination, perceived social inequity, and mental health among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Community Ment Health J 47(2):171–180

Lin T-H, Lin Y-L, Tseng W-L (2016) Manufacturing suicide: the politics of a world factory. Chinese Sociol Rev 48(1):1–32

Liu Z-H, Zhao Y-J, Feng Y, Zhang Q, Zhong B-L, Cheung T, Hall BJ, Xiang Y-T (2020) Migrant workers in China need emergency psychological interventions during the COVID-19 outbreak. Glob Health 16(1):1–3

Lord K, Ibrahim K, Kumar S, Mitchell AJ, Rudd N, Symonds RP (2013) Are depressive symptoms more common among British South Asian patients compared with British white patients with cancer? A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 3(6):e002650

Mao Z-H, Zhao X-D (2012) The effects of social connections on self-rated physical and mental health among internal migrant and local adolescents in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health 12(1):97

Mark G, Smith AP (2012) Occupational stress, job characteristics, coping, and the mental health of nurses. Br J Health Psychol 17(3):505–521

Meltzer H, Bebbington P, Brugha T, Jenkins R, McManus S, Stansfeld S (2010) Job insecurity, socio-economic circumstances and depression. Psychol Med 40(8):1401–1407

Mou J, Cheng J, Griffiths SM, Wong SY, Hillier S, Zhang D (2011) Internal migration and depressive symptoms among migrant factory workers in Shenzhen, China. J Community Psychol 39(2):212–230

Ngai P, Chan J (2012) Global capital, the state, and Chinese workers: the Foxconn experience. Modern China 38(4):383–410

Park S-G, Min K-B, Chang S-J, Kim H-C, Min J-Y (2009) Job stress and depressive symptoms among Korean employees: the effects of culture on work. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 82(3):397

Pompili M, Innamorati M, Narciso V, Kotzalidis G, Dominici G, Talamo A, Girardi P, Lester D, Tatarelli R (2010) Burnout, hopelessness and suicide risk in medical doctors. Clin Ter 161(6):511–514

Qiu P, Caine E, Yang Y, Chen Q, Li J, Ma X (2011) Depression and associated factors in internal migrant workers in China. J Affect Disord 134(1–3):198–207

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1(3):385–401

Sancini A, Ciarrocca M, Capozzella A, Corbosiero P, Fiaschetti M, Caciari T, Cetica C, Scimitto L, Ponticiello BG, Tasciotti Z (2012) Shift and night work and mental health. G Ital Med Lav Ergon 34(1):76–84

Sato K, Kuroda S, Owan H (2020) Mental health effects of long work hours, night and weekend work, and short rest periods. Soc Sci Med 246:112774

Shanbhag D, Joseph B (2012) Mental health status of female workers in private apparel manufacturing industry in Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Public Health 4(12):1893

Shields L, Guevara LF (2020) I can hardly sustain my family: understanding the human cost of the COVID-19 pandemic for workers in the supply Chain. B. H. Project

Shigemi J, Mino Y, Ohtsu T, Tsuda T (2000) Effects of perceived job stress on mental health. A longitudinal survey in a Japanese electronics company. Eur J Epidemiol 16(4):371–376

Song Y, Jia Y, Sznajder K, Ding J, Yang X (2021) Recovery experiences mediate the effect of burnout on life satisfaction among Chinese physicians: a structural equation modeling analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 94(1):31–41

Srivastava A, Arya YK, Joshi S, Singh T, Kaur H, Chauhan H, Das A (2021) Major stressors and coping strategies of internal migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative exploration. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648334

Steffen LE, Smith BW (2013) The influence of between and within-person hope among emergency responders on daily affect in a stress and coping model. J Res Pers 47(6):738–747

Sun IY (2017) The world’s next great manufacturing center. Harv Bus Rev 95(3):122–129

Sun FK, Long A (2013) A suicidal recovery theory to guide individuals on their healing and recovering process following a suicide attempt. J Adv Nurs 69(9):2030–2040

Sun S, Zou J, Zhou X (2012) Investigation on occupational health status and health demand model among female floating workers in Gaomi City. Occup Health 19(28):2329–2331 (in Chinese)

Sznajder KK, Harlow SD, Burgard SA, Wang Y, Han C, Liu J (2014) Gynecologic pain related to occupational stress among female factory workers in Tianjin, China. Int J Occup Environ Health 20(1):33–45

Takaki J, Tsutsumi A, Irimajiri H, Hayama A, Hibino Y, Kanbara S, Sakano N, Ogino K (2010) Possible health-protecting effects of feeling useful to others on symptoms of depression and sleep disturbance in the workplace. J Occup Health 52(5):287–293

Tang S, Li X (2021) Responding to the pandemic as a family unit: social impacts of COVID-19 on rural migrants in China and their coping strategies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8(1):8

Tsuno K, Kawachi I, Inoue A, Nakai S, Tanigaki T, Nagatomi H, Kawakami N (2019) Long working hours and depressive symptoms: moderating effects of gender, socioeconomic status, and job resources. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 92(5):661–672

Virtanen M, Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Ferrie JE, Kivimäki M (2012) Overtime work as a predictor of major depressive episode: a 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. PLoS ONE 7(1):e30719

Wang JJ (2020) How managers use culture and controls to impose a ‘996’ work regime in China that constitutes modern slavery. Acc Finance 60:4331–4359. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12682

Wang C, Tang J (2020) Ritualistic institution and livelihood fragility of female migrant workers in urban China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(24):9556

Wang Z, Xie Z, Dai J, Zhang L, Huang Y, Chen B (2014) Physician burnout and its associated factors: a cross-sectional study in Shanghai. J Occup Health. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.13-0108-oa

Wang Z, Liu H, Yu H, Wu Y, Chang S, Wang L (2017) Associations between occupational stress, burnout and well-being among manufacturing workers: mediating roles of psychological capital and self-esteem. BMC Psychiatry 17(1):364

Whitlock J, Wyman PA, Moore SR (2014) Connectedness and suicide prevention in adolescents: pathways and implications. Suicide Life-Threat Behav 44(3):246–272

Xie Z, Wang A, Chen B (2011) Nurse burnout and its association with occupational stress in a cross-sectional study in Shanghai. J Adv Nurs 67(7):1537–1546

Xu H, Zhang W, Wang X, Yuan J, Tang X, Yin Y, Zhang S, Zhou H, Qu Z, Tian D (2015) Prevalence and influence factors of suicidal ideation among females and males in Northwestern urban China: a population-based epidemiological study. BMC Public Health 15(1):1–13

Xu J, Wang J, Wimo A, Qiu C (2016) The economic burden of mental disorders in China, 2005–2013: implications for health policy. BMC Psychiatry 16:137–137

Yang X, Liu J, Li M, Li P, Wang X, Zeng Q (2018) Effects of occupational stress and related factors on depression symtoms of workers in electronic manufacturing industry. Zhonghua lao dong wei sheng zhi ye bing za zhi= Zhonghua laodong weisheng zhiyebing zazhi= Chinese journal of industrial hygiene and occupational diseases 36(6): 441–444.

Zhang J, Li Z (2013) The association between depression and suicide when hopelessness is controlled for. Compr Psychiatry 54(7):790–796

Zhang J, Yu KF (1998) What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 280(19):1690–1691

Zhang Z-W, Ma L, Liu B (2016) Study on the influencing mechanism between work stress and mental health of electronics manufacturing frontline employees. Chin J Ergonomics 22(1):50–56

Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Sun M (2017) The mental health condition of manufacturing front-line workers: the interrelationship of personal resources, professional tasks and mental health. MATEC Web Conf, EDP Sci 100(2017):05012. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201710005012

Zhong B-L, Liu T-B, Chan S, Jin D, Hu C-Y, Dai J, Chiu H (2018) Common mental health problems in rural-to-urban migrant workers in Shenzhen, China: prevalence and risk factors. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 27(3):256

Zhu C-Y, Wang J-J, Fu X-H, Zhou Z-H, Zhao J, Wang C-X (2012) Correlates of quality of life in China rural–urban female migrate workers. Qual Life Res 21(3):495–503

Zung WW (1986) Zung self-rating depression scale and depression status inventory. Assessment of depression, Springer, pp 221–231

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Tianjin Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for its support on this study and we would especially like to acknowledge the participants of our study for their time.

Funding

The University of Michigan Office for Public Health Practice, the Tianjin Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the 1990 Institute, and the Overseas Young Chinese Forum financially supported this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KKS, SH, and CH contributed to the study conception, study design, and material preparation. KKS and CH performed the data collection. KKS performed the data analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by KKS and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was provided by the University of Michigan and the Tianjin Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Consent to participate

All participants provided consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sznajder, K.K., Harlow, S.D., Wang, J. et al. Factors associated with symptoms of poor mental health among women factory workers in China’s supply chain. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 95, 1209–1219 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01820-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01820-w