- 1Centre for Health Management and Policy Research, School of Public Health, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 2NHC Key Lab of Health Economics and Policy Research, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Binzhou People Hospital, Binzhou, Shandong, China

- 4Department of Pediatrics, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China

Background: Workplace violence (WPV) against medical staff has been an important public health and societal problem worldwide. Although numerous studies have implied the differences between physical violence (PV) and verbal violence (VV) against medical staff, few studies were conducted to analyze the different associations between work-related variables, PV, and VV, especially in China.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among Chinese medical staff in public hospitals, and 3,426 medical staff were interviewed and analyzed. WPV, including PV and VV, were evaluated by the self-report of the medical staff. Work-related variables, physical disease, depression, and social-demographic variables were also measured. The work-related variables included types of medical staff, professional titles, hospital levels, managers, working years, job changing, working hours/week, night duty times/week, monthly income, self-reported working environment, and social position. Logistic regressions were conducted to examine the factors associated with PV and VV.

Results: A total of 489 medical staff (23.0%) reported the experience of PV and 1,744 (50.9%) reported the experience of VV. Several work-related variables were associated with PV and VV, including nurse (OR = 0.56 for PV, p < 0.01; OR = 0.76 for VV, p < 0.05), manager (OR = 1.86 for PV, p < 0.01; OR = 1.56 for VV, p < 0.001), night duty frequency/week (OR = 1.06 for PV, p < 0.01; OR = 1.03 for VV, p < 0.01), bad working environment (OR = 2.73 for PV, p < 0.001; OR = 3.52 for VV, p < 0.001), averaged working environment (OR = 1.51 for PV, p < 0.05; OR = 1.55 for VV, p < 0.001), and bad social position (OR = 4.21 for PV, p < 0.001; OR = 3.32 for VV, p < 0.001). Working years (OR = 1.02, p < 0.05), job changing (OR = 1.33, p < 0.05), and L2 income level (OR = 1.33, p < 0.01) were positively associated with VV, but the associations were not supported for PV (all p>0.05). The other associated factors were male gender (OR = 1.97 for PV, p < 0.001; OR = 1.28 for VV, p < 0.05) and depression (OR = 1.05 for PV, p < 0.001; OR = 1.04 for VV, p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Both PV and VV were positively associated with work-related variables, such as doctor, manager, more night duty frequency, perceived bad working environment, or social position. Some variables were only associated with VV, such as working years, job changing, and monthly income. Some special strategies for the work-related variables should be applied for controlling PV and VV.

1. Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) defined workplace violence (WPV) as “incidents where staff is abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances related to their work” (1). In recent decades, several studies reported that more than 60% of medical staff have experienced WPV in the world (2–4). In China, the prevalence of WPV against medical staff appears to be on the rise in recent years (5, 6). In addition, previous studies also identified several negative outcomes of WPV, such as depressive symptoms, cardiovascular disease, and so on (7–9). We have enough reasons to conclude that WPV against medical staff has been an important public health and societal problem worldwide (10, 11), which should gain our attention.

Due to the importance of WPV, several studies had been conducted to explore the factors associated with WPV against medical staff, and several associated factors were identified, such as social-demographic (12, 13), psychological and physical health (9, 14–18), and work-related variables (19–22). For work-related variables, most of these studies focused on the association between work stress, work burnout, social support, work environment, and WPV (19–22). The work for medical staff was characterized by long working hours, frequent night duty, and a high workload (23, 24). However, only a few studies were conducted to explore the associations between these work-related variables and WPV (25–27). When we further reviewed these studies, most of them were conducted among special kinds of medical staff in China, such as general practitioners (28) and nurses (29). China is the country with the highest population and the most health services in the world (30), and the seriousness and social impact of WPV were also at a high level (6, 31). Thus, studies about the associations between work-related variables and WPV in China not only can help us to build associations with a wider range of medical staff but also can help us to supply the evidence to control WPV in the world.

In contrast, physical violence (PV) and verbal violence (VV) were the main classifications for WPV against medical staff. In recent years, studies have identified a higher prevalence of VV than PV among medical staff (32, 33). Another study also supported that nurses were at higher risk of PV and doctors were at higher risk of VV (34). In Turkey, one study supported that average working time per week was associated with PV but not with VV among nurses (35). All these findings implied that there may be some differences between PV and VV. However, fewer studies were conducted to explore the differences between PV and VV, especially in China.

To fill the gaps, we conducted a cross-sectional study among Chinese medical staff. In this study, our first aim was to explore the associations between work-related variables and WPV among a wider range of medical staff. The second aim was to explore the differences in work-related variables between PV and VV among medical staff. The findings help us better understand the associations between work-related variables and WPV in the world, and they can also provide us with special strategies to control PV and VV against medical staff.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting and participants

This is a cross-sectional study conducted among medical staff in Shandong Province, China. Shandong Province is located in the east of China, and its population ranks second among all the Chinese provinces (36). The number of health workers in Shandong province ranked first in all the Chinese provinces (37). In this study, we used multiple stratified random cluster sampling methods to recruit medical staff in general hospitals. First, all 17 cities in Shandong were divided into three levels based on the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in 2018 (36), and one city was randomly selected from each level. Second, we randomly selected one municipal hospital from each of the selected cities. In this step, three counties (districts) were also randomly selected from each of the selected cities. Third, the general county-level hospitals (district-level hospitals) in the selected counties (districts) were chosen to conduct this study. Finally, we selected three municipal hospitals and nine county-level hospitals. In these hospitals, three inpatient areas from each department were randomly selected in municipal hospitals, and two inpatient areas from each department were randomly selected in county-level hospitals. Medical staff, including doctors, nurses, and medical technicians, who worked on the interview date were recruited to participate in the survey. We interviewed and analyzed 3,426 medical staff in this study. The ratios for sample size and analyzed variables should be higher than 5. In this study, we analyzed 17 variables, and the smallest analyzed sample size was 2,127, which is adequate for the data analyses.

2.2. Data collection

This study was conducted from December 2018 to January 2019. The questionnaires were sent to medical staff individually, and they filled them out anonymously. On the interview date, two trained postgraduate students were stationed in the hospital to answer the questions and collect the questionnaires. Totally, we trained eight postgraduate students to complete the survey in one city.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Workplace violence, verbal violence, and physical violence

Workplace violence (WPV) was assessed by the question, “Have you ever experienced the following behavior conducted by your patients or their relations?” The answers were verbal violence, physical violence, both verbal and physical violence (BV), and no violence (NV). In this study, physical violence (PV) was recoded as yes (1) or no (0), with the former one including medical staff reporting physical violence and BV. VV was also recoded as yes (1) or no (0), with the former one including medical staff reporting verbal violence and BV. This question has been used to evaluate WPV in many previous studies (32, 38, 39).

2.3.2. Work-related variables

In this study, the work-related variables contained types of medical staff, professional titles, hospital levels, managers, working years, job changing, working hours/week, night duty times/week, monthly income, self-reported working environment, and self-reported social position. Types of medical staff included doctors (1), nurses (2), and medical technicians (3). The professional title was evaluated by senior (1), vice-senior (2), intermediate (3), and junior and others (4). As this study was conducted among municipal and county-level hospitals, there was no level 1 hospital. Hospital level was measured by level 2 (0) and level 3 (1). The manager was measured by yes (1) or no (0), and the former one contained the dean/vice-dean, director/vice-director, and change nurse. Job changing was also evaluated by yes (1) or no (0), and medical staff who had full-time labor in other institutions were marked true for job changing. Working hours per week were evaluated by the question, “How many hours do you work per week on average?” The participants answered the number of hours per week that they worked. The number of working hours/week was analyzed in this study. Night duty frequency/week was measured by the average times of night duty for the participants. Income level was evaluated by the question about the income of the participants, including salary, bonus, and all the other kinds of income. The answers can be chosen from ≤ 3,000 RMB, 3,001–5,000 RMB, 5,001–7,000 RMB, 7,001–9,000 RMB, 9,001–11,000 RMB, 11,001–13,000 RMB, and ≥13,001 RMB. As fewer participants chose the last 3 answers, we recoded them as follows: ≤ 5,000 RMB (L1), 5,001–9,000 RMB (L2), and ≥9,001 RMB (L3). A US dollar is approximately equal to 7 RMB. The working environment was evaluated by the self-reported question, “What do you think about your current working environment?” The answer contained very good, good, average, bad, and very bad. We recoded them into good (1), average (2), and bad (3). The good classification contained very good and good options, and the bad classification contained bad and very bad options. Social position was also evaluated by the self-reported question, “What do you think about your current social position?” The answer also contained very good, good, average, bad, and very bad. We recoded them into good (1), average (2), and bad (3). The good classification contained very good and good options, and the bad classification contained bad and very bad options.

2.3.3. Social-demographic variables

Gender was coded as male (0) and female (1). Age was calculated by the date of birth of the participants. Marital status was evaluated by single, married, divorced, widowed, and others. As the percentage of the last three answers was small, we recoded it as single (1), married (2), and others (3). Education was assessed by the academic degree received by the participants. The answers were doctor, master, bachelor, junior college, secondary specialized school, high school, middle school, or below. As the percentage of the last four answers was small, we recoded it as a doctor (1), master (2), bachelor (3), and others (4).

2.3.4. Physical disease

The physical disease was evaluated by the question, “If you have been diagnosed with any physical disease?” The answer was yes (1) and no (0).

2.3.5. Depression

Depression was evaluated by the Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) (40). In this scale, there were 20 items to evaluate the feeling of the subjects in the last week. The answer can be chosen from 0 (< 1 day), 1 (1–2 days), 2 (3–4 days), and 3 (5–7 days). The higher scores mean a higher risk of depression. The CES-D was also identified as having nice reliability and validity in the world (41, 42), and the Chinese version of the CES-D was also tested with good reliability and validity (43). In this study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.852.

2.4. Statistical analysis

In this study, IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 (Web Edition) was used to conduct the data analyses. T-tests or one-way ANOVA were performed to analyze the factors associated with PV and VV. Logistic regression was conducted to further examine the factors associated with PV and VV. All the tests were two-tailed, and a p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

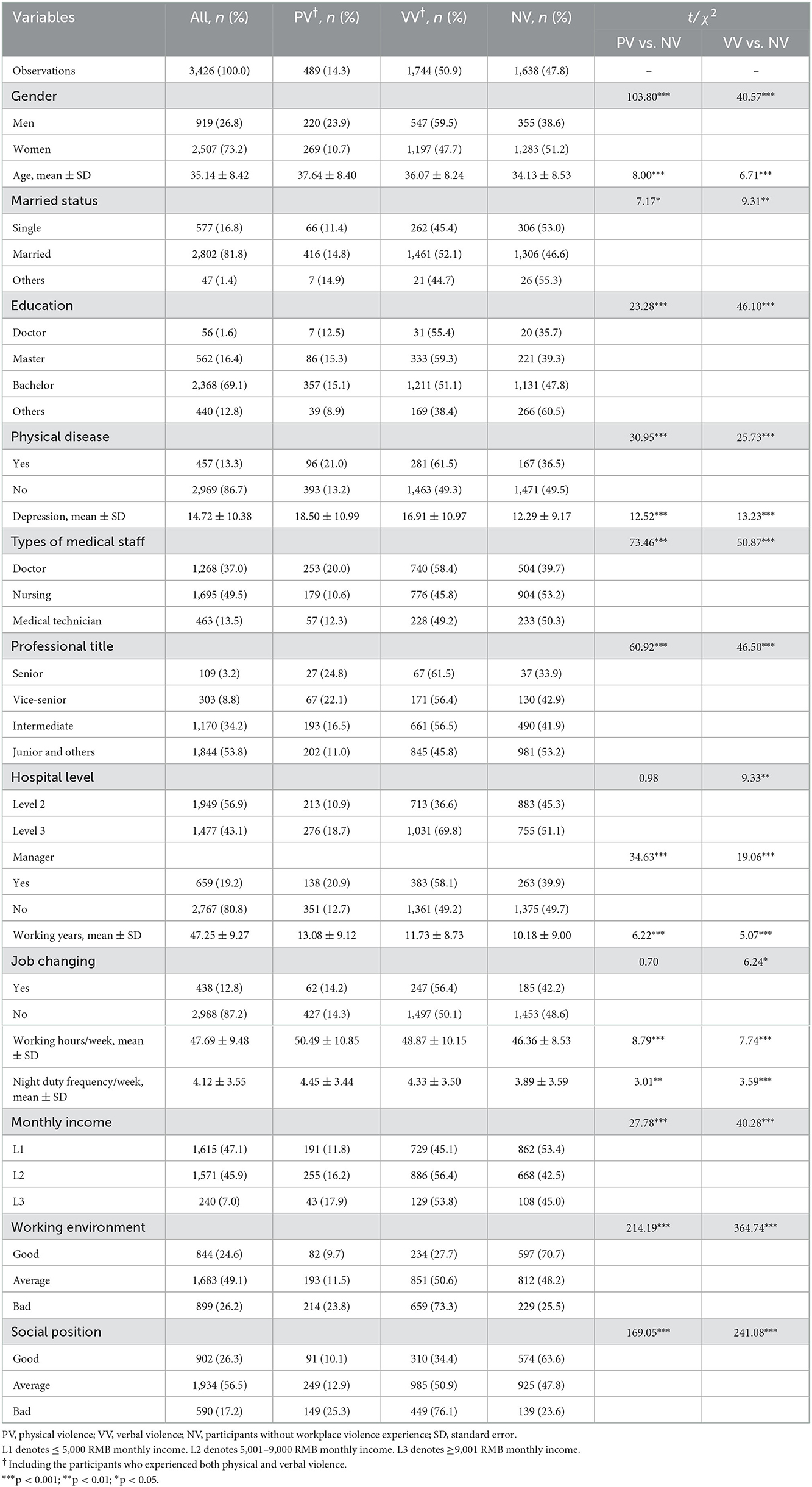

In Table 1, the descriptive analyses are shown in the second column. In the third line, 489 medical staff (23.0%) reported the experience of PV, and 1,744 (50.9%) reported the experience of VV. Single-factor analyses were also conducted to explore the factors associated with PV and VV. The factors associated with PV were gender (χ2 = 103.80, p < 0.001), age (t = 8.00, p < 0.001), marital status (χ2 = 7.17, p < 0.05), education (χ2 = 23.28, p < 0.001), physical disease (χ2 = 30.95, p < 0.001), depression (t = 12.52, p < 0.001), types of medical staff (χ2 = 73.46, p < 0.001), professional title (χ2 = 60.92, p < 0.001), manager (χ2 = 34.63, p < 0.001), working years (t = 6.22, p < 0.001), working hours/week (t = 8.79, p < 0.001), night duty frequency/week (t = 3.01, p < 0.01), monthly income (χ2 = 27.78, p < 0.001), working environment (χ2 = 214.19, p < 0.001), and social position (χ2 = 169.05, p < 0.001). Similar associated factors were also supported for VV, with additions of hospital level (χ2 = 9.33, p < 0.001) and job changing (χ2 = 6.24, p < 0.05). The detailed information can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Percentage and single-factor analyses for factors associated with reported physical/verbal violence among medical staff in Shandong, China.

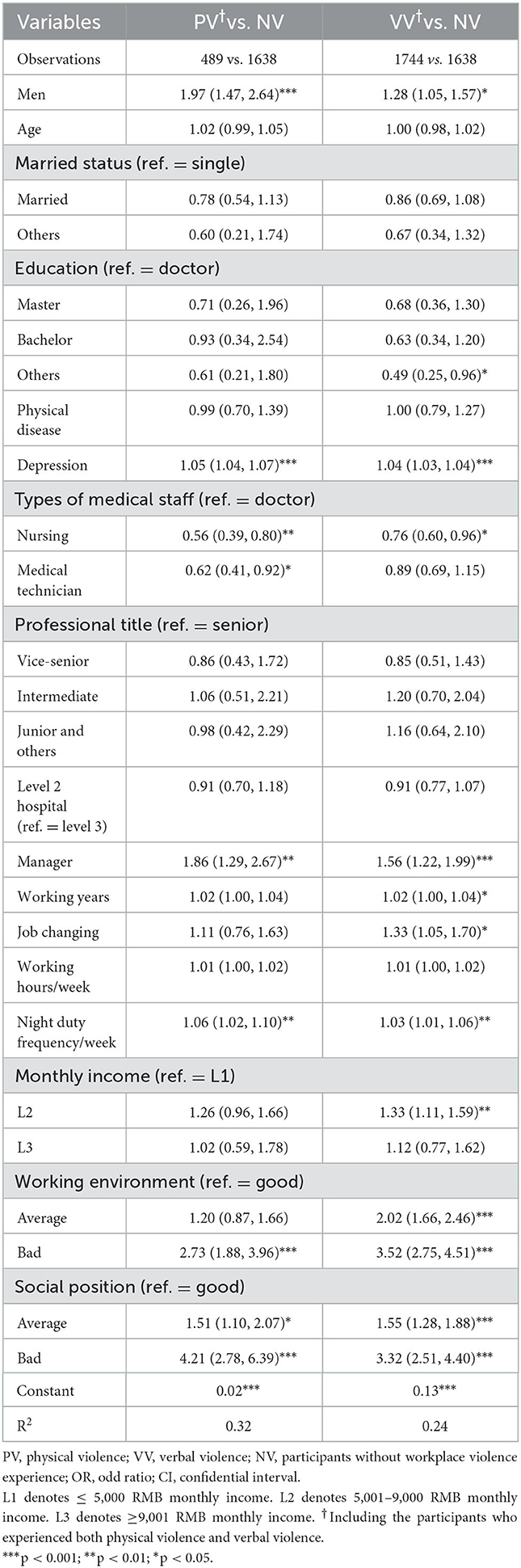

Logistic regressions were further conducted to analyze the factors associated with PV and VV. The results supported that the factors associated with PV were male gender (OR = 1.97, p < 0.001), depression (OR = 1.05, p < 0.001), nurse (OR = 0.56, p < 0.01), medical technician (OR = 0.62, p < 0.05), manager (OR = 1.86, p < 0.01), night duty frequency/week (OR = 1.06, p < 0.01), bad working environment (OR = 2.73, p < 0.001), averaged social position (OR = 1.51, p < 0.05), and bad social position (OR = 4.21, p < 0.001). The factors associated with VV were male gender (OR = 1.28, p < 0.05), other education (OR = 0.49, p < 0.05), depression (OR = 1.04, p < 0.001), nurse (OR = 0.76, p < 0.05), manager (OR = 1.56, p < 0.001), working years (OR = 1.02, p < 0.05), job changing (OR = 1.33, p < 0.05), night duty frequency/week (OR = 1.03, p < 0.01), L2 income level (OR = 1.33, p < 0.01), averaged working environment (OR = 2.02, p < 0.001), bad working environment (OR = 3.52, p < 0.001), averaged social position (OR = 1.55, p < 0.001), and bad social position (OR = 3.32, p < 0.001). The detailed results can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Logistic regression analyses for the factors associated with physical violence among medical staff in Shandong, China [OR (95% CI)].

4. Discussion

In this study, there were several critical findings. First, we found that more than half of the medical staff (52.2%) experienced WPV. The percentage for PV against medical staff was 14.3%, and it was 50.9% for VV. Second, both PV and VV were associated with several work-related variables, such as types of medical staff, manager, night duty frequency, self-reported working environment, and self-reported social position. The other risk factors were male gender and depression. Third, VV was positively associated with working years, job changing, and monthly income. However, these work-related variables were not supported as being associated with PV.

The first finding in this study was about the prevalence of WPV, PV, and VV among medical staff, and we found that 52.2% of medical staff reported WPV, 14.3% of medical staff reported PV, and 50.9% of medical staff reported VV. Compared with other studies, this prevalence of WPV, PV, and VV was slightly lower than that in other studies. This prevalence of WPV was 54.8% among nurses in Turkey (44) and 71.9% among medical staff at primary hospitals (45). For the prevalence of PV and VV, they were also ~20% and 70%, respectively (46, 47). One of the explanations was about the different current situations of WPV among doctors, nurses, and medical technicians (48). In this study, we interviewed medical technicians who have a lower prevalence of WPV (49). The other reason may be explained by cultural differences in the perception of WPV in different countries. Harmonization is one of the characteristics of Chinese Confucian culture (50). Shandong Province was also the headstream of Confucian culture, which was also deeply influenced by this culture. This kind of harmonization may also reduce the occurrence of WPV against medical staff.

In this study, a higher prevalence of PV and VV was reported among doctors and managers, which was also supported in previous studies (32, 47, 51). Doctors need to take charge of the therapeutic plan and frequently communicate with patients. Dissatisfaction with the professional diagnosis and treatment processes was one of the main reasons for hospital violence (52), and it may explain why doctors are at a higher risk of WPV than nurses and medical technicians. Managers need to deal with the problems of patients in their departments, and they frequently communicate with patients and their relatives about healthcare problems. This means that they are also at higher risk of PV and VV.

The other finding in this study was about the associations between night duty frequency, self-reported working environment, self-reported social position, and WPV (including PV and VV). The positive association between more night duty frequency and WPV was also supported by previous studies (29). One of the explanations was about the identified associated factors, such as job burnout (53) and poor sleep quality (54). Some studies supported the fact that most WPV happened at night (55). The findings in the study also supported the fact that a bad self-reported working environment and a bad self-reported social position were also positively associated with WPV. They may have a bidirectional causal relationship. Medical staff who experienced WPV may feel a worse working environment or social position. Medical staff with the feeling of a worse working environment and social position may be at a higher risk of psychological health, which is also a risk factor for WPV (56, 57).

We also found that VV was positively associated with working years and monthly income, but both were not supported as being associated with PV. In this study, VV was evaluated in a lifetime. Medical staff with longer work years were also in longer communication with the patients and their relatives, and they were also at higher risk of VV. The positive association between monthly income level and VV may be explained by the more diagnosis and treatment chance. In China, the income of the medical staff is positively associated with the number of health services, and more quantity of health services increases the risk of VV among the patients and their relatives. However, when we went to PV, the associations were not supported in this study. One of the reasons may be the serious consequences of PV (9, 58, 59). The patients and their relatives may also be cautious about conducting PV. However, previous studies supported the fact that PV is mainly caused by dissatisfaction with the attitude of the medical staff (34). Medical staff with long working years may have experience with the attitude, and it may weaken the association between working years and PV.

We also found that job changing was positively associated with VV but not with PV. Some studies supported the associations between job changing and workplace violence (60). This association may be explained by job satisfaction. Previous studies identified that medical staff with low job satisfaction were at higher risk of workplace violence (61, 62), and it also increased their intention to leave (63). However, this study did not support the association between job changing and PV. One of the reasons may be the small sample size for PV. The other reason may be mental stress from the PV experiences. Medical staff with PV experiences may feel mental stress, and some working environment change may be helpful for them to reduce the mental stress, and job changing may be one method of changing the working environment.

Both gender and depression were also associated with WPV in this study. For gender, we found that the female gender was at a lower risk of experiencing WPV compared with the male gender. This is different from other findings in Western countries, which found female health workers were at higher risk of WPV (64). This may be explained by the Confucian culture of the weak female gender in China (65). Medical staff with depression may find it hard to supply good quality medical services, and it may further result in WPV. In contrast, depression may also be one of the negative outcomes of WPV, which was supported by previous studies (58).

Although there were some significant findings in this study, several limitations should be considered when we interpret the results. First, we cannot get any causal relationships for the association between work-related variables and WPV because of the cross-sectional design. Second, all the factors analyzed in this study were collected by self-reporting of medical staff, and it may also bring some bias to the findings in this study. Third, the data analyzed in this study were collected from several general hospitals in Shandong Province, China. The multiple stratified random cluster sampling method may overrepresent the situations in economically developed cities, and we should also be cautious when extending the findings to other regions or countries.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we found that both PV and VV had a higher prevalence among medical staff in Shandong, China. Both PV and VV were positively associated with doctor, manager, more night duty frequency, perceived bad working environment, or social position. VV was positively associated with more working years, job changing, and more monthly income, but they were not supported to be associated with PV. These findings remind us that work-related variables were associated with WPV, and there were some different associated factors between PV and VV. Some special strategies about the work-related variables should be applied for controlling WPV, and the differences between PV and VV should also arouse our attention.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shandong University School of Public Health. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LS analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. WZ collected the data and comment on the draft of this manuscript. AC designed the study and revised the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71974114).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants for their participation in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. (ILO) ILO, (ICN) ICoN, (WHO) WHO, (PSI) PSI. Framework Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. Geneva: Office IL (2002).

2. Varghese A, Joseph J, Vijay VR, Khakha DC, Dhandapani M, Gigini G, et al. Prevalence and determinants of workplace violence among nurses in the South-East Asian and Western Pacific Regions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. (2021) 31:798–819. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15987

3. Aljohani B, Burkholder J, Tran QK, Chen C, Beisenova K, Pourmand A. Workplace violence in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. (2021) 196:186–97. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.009

4. Odes R, Chapman S, Harrison R, Ackerman S, Hong O. Frequency of violence towards healthcare workers in the United States' inpatient psychiatric hospitals: a systematic review of literature. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2021) 30:27–46. doi: 10.1111/inm.12812

5. Hall BJ, Xiong P, Chang K, Yin M, Sui XR. Prevalence of medical workplace violence and the shortage of secondary and tertiary interventions among healthcare workers in China. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2018) 72:516–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-208602

6. Zhang X, Li Y, Yang C, Jiang G. Trends in workplace violence involving health care professionals in China from 2000 to 2020: a review. Med Sci Monit. (2021) 27:e928393. doi: 10.12659/MSM.928393

7. Cai R, Tang J, Deng C, Lv G, Xu X, Sylvia S, et al. Violence against health care workers in China, 2013–2016: evidence from the national judgment documents. Hum Resour Health. (2019) 17:103. doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0440-y

8. Hsieh HF, Chen YM, Wang HH, Chang SC, Ma SC. Association among components of resilience and workplace violence-related depression among emergency department nurses in Taiwan: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. (2016) 25:2639–47. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13309

9. Xu T, Magnusson Hanson LL, Lange T, Starkopf L, Westerlund H, Madsen IEH, et al. Workplace bullying and workplace violence as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a multi-cohort study. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40:1124–34. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy683

10. Yang Z, Liu Y, Fan D. Workplace Violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375:e14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1606816

11. Pompeii L, Benavides E, Pop O, Rojas Y, Emery R, Delclos G, et al. Workplace violence in outpatient physician clinics: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:6587. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186587

12. Dagnaw EH, Bayabil AW, Yimer TS, Nigussie TS. Working in labor and delivery unit increases the odds of work place violence in Amhara region referral hospitals: cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0254962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254962

13. MacGregor JCD, Naeemzadah N, Oliver CL, Javan T, MacQuarrie BJ, Wathen CN. Women's experiences of the intersections of work and intimate partner violence: a review of qualitative research. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2022) 23:224–40. doi: 10.1177/1524838020933861

14. Rudkjoebing LA, Hansen AM, Rugulies R, Kolstad H, Bonde JP. Exposure to workplace violence and threats and risk of depression: a prospective study. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2021) 47:582–90. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3976

15. Magnavita N. The exploding spark: workplace violence in an infectious disease hospital—a longitudinal study. Biomed Res Int. (2013) 2013:316358. doi: 10.1155/2013/316358

16. Kim HR. Associations between workplace violence, mental health, and physical health among Korean Workers: the fifth Korean working conditions survey. Workplace Health Saf. (2021) 29:21650799211023863. doi: 10.1177/21650799211023863

17. Marquez SM, Chang CH, Arnetz J. Effects of a workplace violence intervention on hospital employee perceptions of organizational safety. J Occup Environ Med. (2020) 62:e716–24. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002036

18. Zhu PP, Chen LY, Pan JH, Kang CJ, Ye XM, Ye JY, et al. The symptoms and factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder for burns nurses: a cross-sectional study from Guangdong province in China. J Burn Care Res. (2021) 43:189–95. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irab121

19. Sun X, Qiao M, Deng J, Zhang J, Pan J, Zhang X, et al. Mediating effect of work stress on the associations between psychological job demands, social approval, and workplace violence among health care workers in Sichuan province of China. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:743626. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.743626

20. Converso D, Sottimano I, Balducci C. Violence exposure and burnout in healthcare sector: mediating role of work ability. Med Lav. (2021) 112:58–67. doi: 10.23749/mdl.v112i1.9906

21. Balducci C, Vignoli M, Dalla Rosa G, Consiglio C. High strain and low social support at work as risk factors for being the target of third-party workplace violence among healthcare sector workers. Med Lav. (2020) 111:388–98. doi: 10.23749/mdl.v111i5.9910

22. Wu Y, Wang J, Liu J, Zheng J, Liu K, Baggs JG, et al. The impact of work environment on workplace violence, burnout and work attitudes for hospital nurses: A structural equation modelling analysis. J Nurs Manag. (2020) 28:495–503. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12947

23. Zhang L, Wang F, Cheng Y, Zhang P, Liang Y. Work characteristics and psychological symptoms among GPs and community nurses: a preliminary investigation in China. Int J Qual Health Care. (2016) 28:709–14. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw098

24. Schwartz WB, Mendelson DN. No evidence of an emerging physician surplus. An analysis of change in physicians' work load and income. JAMA. (1990) 263:557–60.

25. Bayram B, Cetin M, Colak Oray N, Can IO. Workplace violence against physicians in Turkey's emergency departments: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013568. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013568

26. Jafree SR. Workplace violence against women nurses working in two public sector hospitals of Lahore, Pakistan. Nurs Outlook. (2017) 65:420–7. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.01.008

27. Wong AH, Sabounchi NS, Roncallo HR, Ray JM, Heckmann R. A qualitative system dynamics model for effects of workplace violence and clinician burnout on agitation management in the emergency department. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22:75. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07472-x

28. Gan Y, Li L, Jiang H, Lu K, Yan S, Cao S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with workplace violence against general practitioners in Hubei, China. Am J Public Health. (2018) 108:1223–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304519

29. Li S, Yan H, Qiao S, Chang X. Prevalence, influencing factors and adverse consequences of workplace violence against nurses in China: a cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag. (2022) 30:1801–10. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13717

30. United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs PD. Global Population Growth and Sustainable Development. New York, USA: United Nations (2021). Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?end=2020&most_recent_value_desc=true&start=2020&view=map (accessed November 28, 2022).

31. Teoh RJJ, Lu F, Zhang XQ. Workplace violence against healthcare professionals in China: a content analysis of media reports. Indian J Med Ethics. (2019) 4:95–100. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2019.006

32. Sun L, Zhang W, Qi F, Wang Y. Gender differences for the prevalence and risk factors of workplace violence among healthcare professionals in Shandong, China. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:873936. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.873936

33. Chen Y, Wang P, Zhao L, He Y, Chen N, Liu H, et al. Workplace Violence and turnover intention among psychiatrists in a national sample in China: the mediating effects of mental health. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:855584. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.855584

34. Jia C, Han Y, Lu W, Li R, Liu W, Jiang J. Prevalence, characteristics, and consequences of verbal and physical violence against healthcare staff in Chinese hospitals during 2010–2020. J Occup Health. (2022) 64:e12341. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12341

35. Aksakal FN, Karasahin EF, Dikmen AU, Avci E, Ozkan S. Workplace physical violence, verbal violence, and mobbing experienced by nurses at a university hospital. Turk J Med Sci. (2015) 45:1360–8. doi: 10.3906/sag-1405-65

37. NHC. Chinese Health Statistics Yearbook 2019. Beijing: China Union Medical College Press (2019).

38. Torok E, Rod NH, Ersboll AK, Jensen JH, Rugulies R, Clark AJ. Can work-unit social capital buffer the association between workplace violence and long-term sickness absence? A prospective cohort study of healthcare employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. (2020) 93:355–64. doi: 10.1007/s00420-019-01484-7

39. Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Ager J, Luborsky M, Upfal MJ, Russell J, et al. Underreporting of workplace violence: comparison of self-report and actual documentation of hospital incidents. Workplace Health Saf. (2015) 63:200–10. doi: 10.1177/2165079915574684

40. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. (1977) 1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

41. Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D Scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Res. (1980) 2:125–34. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4

42. Roberts RE, Rhoades HM, Vernon SW. Using the CES-D scale to screen for depression and anxiety: effects of language and ethnic status. Psychiatry Res. (1990) 31:69–83.

43. Jiang L, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Li R, Wu H, Li C, et al. The reliability and validity of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) for Chinese University students. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:315. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00315

44. Cam HH, Ustuner Top F. Workplace violence against nurses working in the public hospitals in Giresun, Turkey: prevalence, risk factors, and quality of life consequences. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2021) 57:e29–33. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12978

45. Zhu H, Liu X, Yao L, Zhou L, Qin J, Zhu C, et al. Workplace violence in primary hospitals and associated risk factors: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Open. (2022) 9:513–8. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1090

46. Sahebi A, Golitaleb M, Moayedi S, Torres M, Sheikhbardsiri H. Prevalence of workplace violence against health care workers in hospital and pre-hospital settings: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:895818. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.895818

47. Alnofaiey YH, Alnfeeiye FM, Alotaibi OM, Aloufi AA, Althobaiti SF, Aljuaid AG. Workplace violence toward emergency medicine physicians in the hospitals of Taif city, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Emerg Med. (2022) 22:59. doi: 10.1186/s12873-022-00620-w

48. Tian K, Xiao X, Zeng R, Xia W, Feng J, Gan Y, Zhou Y. Prevalence of workplace violence against general practitioners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Health Plann Manage. (2021) 37:1238–51. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3404

49. Wang PY, Fang PH, Wu CL, Hsu HC, Lin CH. Workplace violence in Asian Emergency Medical Services: a pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:3936. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16203936

50. Lan L, Zhu Q, Liu Y. The rule of virtue: a Confucian response to the ethical challenges of technocracy. Sci Eng Ethics. (2021) 27:64. doi: 10.1007/s11948-021-00341-6

51. Park J, Choi S, Sung Y, Chung J, Choi S. Workplace violence against female health managers in the male-dominated construction industry. Ann Work Expo Health. (2022) 66:1224–30. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxac025

52. Xiao Y, Du N, Chen J, Li YL, Qiu QM, Zhu SY. Workplace violence against doctors in China: a case analysis of the Civil Aviation General Hospital incident. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:978322. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.978322

53. Schablon A, Kersten JF, Nienhaus A, Kottkamp HW, Schnieder W, Ullrich G, et al. Risk of burnout among emergency department staff as a result of violence and aggression from patients and their relatives. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:94945. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19094945

54. Membrive-Jimenez MJ, Gomez-Urquiza JL, Suleiman-Martos N, Velando-Soriano A, Ariza T, et al. Relation between burnout and sleep problems in nurses: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel). (2022) 10:954. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10050954

55. Kader SB, Rahman MM, Hasan MK, Hossain MM, Saba J, Kaufman S, et al. Workplace violence against doctors in Bangladesh: a content analysis. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:787221. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.787221

56. Lee N-R, Kim S-W, Joo J-H, Lee J-H, Lee J-H, Lee K-J. Relationship between workplace violence and work-related depression/anxiety, separating the types of perpetrators: a cross-sectional study using data from the fourth and fifth Korean Working Conditions Surveys (KWCS). Ann Occup Environ Med. (2022) 10:e13. doi: 10.35371/aoem.2022.34.e13

57. Wang L, Ni X, Li Z, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, et al. Mental health status of medical staff exposed to hospital workplace violence: a prospective cohort study. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:930118. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.930118

58. Wang H, Zhang Y, Sun L. The effect of workplace violence on depression among medical staff in China: the mediating role of interpersonal distrust. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. (2021) 94:557–64. doi: 10.1007/s00420-020-01607-5

59. Alsmael MM, Gorab AH, AlQahtani AM. Violence against healthcare workers at primary care centers in Dammam and Al Khobar, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia, 2019. Int J Gen Med. (2020) 13:667–76. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S267446

60. Budd JW, Arvey RD, Lawless P. Correlates and consequences of workplace violence. J Occup Health Psychol. (1996) 1:197–210. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.1.2.197

61. Ferrara P, Terzoni S, Destrebecq A, Ruta F, Sala E, Formenti P, Maugeri M. Violence and unsafety in Italian hospitals: experience and perceptions of nursing students. Work. (2022) 2022:1–7. doi: 10.3233/WOR-210488

62. Kim S, Gu M, Sok S. Relationships between violence experience, resilience, and the nursing performance of emergency room nurses in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:2617. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19052617

63. Stafford S, Avsar P, Nugent L, O'Connor T, Moore Z, Patton D, Watson C. What is the impact of patient violence in the emergency department on emergency nurses' intention to leave? J Nurs Manag. (2022) 30:1852–60. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13728

64. Ielapi N, Andreucci M, Bracale UM, Costa D, Bevacqua E, Giannotta N, et al. Workplace violence towards healthcare workers: an Italian cross-sectional survey. Nurs Rep. (2021) 11:758–64. doi: 10.3390/nursrep11040072

Keywords: physical violence, verbal violence, work-related variables, medical staff, China

Citation: Sun L, Zhang W and Cao A (2023) Associations between work-related variables and workplace violence among Chinese medical staff: A comparison between physical and verbal violence. Front. Public Health 10:1043023. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1043023

Received: 13 September 2022; Accepted: 19 December 2022;

Published: 10 January 2023.

Edited by:

Francesco Chirico, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Yanhong Gong, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, ChinaYongsheng Tong, Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, Peking University, China

Xiaoxv Yin, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China

Copyright © 2023 Sun, Zhang and Cao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aihua Cao,  xinercah@163.com

xinercah@163.com

Long Sun

Long Sun Wen Zhang3

Wen Zhang3 Aihua Cao

Aihua Cao