Abstract

Over the last 20 years, virtual reality (VR) has gained a great interest for both assessment and treatment of various psychopathologies. However, due to high costs and material specificity, VR remains disadvantageous for clinicians. Adopting a multiple transdiagnostic approach, this study aims at testing the validity of a 360-degree immersive video (360IV) for the assessment of five common psychological symptoms (fear of negative evaluation, paranoid thoughts, negative automatic thoughts, craving for alcohol and for nicotine). A 360IV was constructed in the Darius Café and included actors behaving naturally. One hundred and fifty-eight adults from the general population were assessed in terms of their proneness towards the five symptoms, were then exposed to the 360IV and completed measures for the five state symptoms, four dimensions of presence (place, plausibility, copresence and social presence illusions) and cybersickness. Results revealed that the five symptoms occurred during the immersion and were predicted by the participants’ proneness towards these symptoms. The 360IV was also able to elicit various levels of the four dimensions of presence while producing few cybersickness. The present study provides evidence supporting the use of the 360IV as a new accessible, ecological, and standardized tool to assess multiple transdiagnostic symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the last 20 years, immersive technologies, and principally virtual reality (VR), have gained a great interest in various areas of psychopathology such as social anxiety (Emmelkamp et al. 2020), paranoia (Rus-Calafell et al. 2018) or substance abuse (Bordnick and Washburn 2019; Segawa et al. 2020). The main advantage of VR is to generate various secure ecological real-world experiences, which are able to elicit realistic cognitive and emotional reactions (Diemer et al. 2015; Riva et al. 2007). In clinical settings, immersive technologies have the potential to be used for both the assessment and treatment of psychological disorders (Riva and Serino 2020). In particular, the efficacy of VR-based psychological treatments for several types of disorders has been highlighted in numerous studies (for reviews and meta-analyses, see Cieślik et al. 2020; Dellazizzo et al. 2020).

Even though the use of VR experiences appears empirically grounded, their use remains relatively limited for most clinicians. This phenomenon might be explained by at least three important reasons. A first reason is that the license acquisition for virtual environments is particularly expensive and gives access only to a limited number of virtual situations (Della Libera et al. 2021). A second reason is that these environments are mostly designed to treat one unique disorder, leading clinicians to need numerous licenses for a few specific patients. And finally, the existence of virtual environments that fulfill the complete criteria for psychological assessment (e.g., test–retest indices, norms, and cut-off scores) remains poor (Geraets et al. 2021). Besides these limitations, technological developments of the last few years have allowed access to novel immersive experiences through 360-degree immersive videos (360IV). Compared to VR, a 360IV consists of an accessible tool which can rely on pre-existing materials (e.g., YouTube videos) but also allows the creation of one’s own material with the help of an affordable 360-degree camera, while at the same time not requiring advanced software skills (Kittel et al. 2020; Riva and Serino 2020). Further, contrasting with virtual avatars, 360IV provides photorealistic immersive experiences where the complexity of social interactions, including facial and bodily expressions, can be faithfully rendered (Kittel et al. 2020).

Although the advantages of 360IVs in terms of accessibility and realism are considerable, it is noteworthy that they come at the expense of the environment’s responsiveness (Pandita and Won 2020). This means that, despite the possibility for participants to turn their head around 360°, they are unable to move or interact with the scenario. In spite of this shortcoming, 360IVs have been shown to elicit realistic emotional-cognitive reactions in three studies investigating the occurrence of social anxiety (Barreda-Ángeles et al. 2020; Holmberg et al. 2020; Della Libera et al. 2020). In a first study, Barreda-Ángeles et al. (2020) compared the psychophysiological reactions of 36 non-clinical participants delivering a speech in front of a positive, neutral, and negative audience. Compared to the neutral audience, the negative audience was associated with higher levels of self-reported anxiety, lower voice intensity as well as increases of skin conductance and heart rate variability. A second study (Holmberg et al. 2020) compared the responses of 9 social anxious participants and 9 healthy controls to a 360IV shopping session. Social anxious participants reported higher levels of anxiety before, during and after the immersion than controls. Finally, a third study (Della Libera et al. 2021) examined the occurrence of paranoid thoughts in 150 healthy participants exposed to a 360IV representing either a lift, a library, or a bar. With the help of quantitative and qualitative assessments, the results revealed that participants reported various interpretations about the actors’ intentions including paranoid ones. In addition, the occurrence of paranoid thoughts was significantly predicted by the proneness towards trait paranoia. Overall, these studies suggest that 360IVs can elicit realistic emotional-cognitive reactions and seem to be an eligible alternative immersive tool for the assessment of psychopathological symptoms.

When creating a new immersive experience, one important aspect to consider is its immersive properties. These include its ability to limit (or completely avoid) cybersickness (Pan and Hamilton 2018) and elicit a sense of presence into the immersive experience (i.e., a cognitive feeling or perceptual illusion of “being there” in the immersive environment (Schubert et al. 1999; Slater and Wilbur 1997). Since the sense of presence is considered a necessary condition for realistic emotional and cognitive reactions (see Diemer et al. 2015; Parson and Rizzo 2008; Schutte and Stilinović 2017), its dimensions deserve to be further defined. Overall, four dimensions—referred to as “illusions”—of the sense of presence have been highlighted (Biocca et al. 2003; Felnhofer et al. 2019; Slater 2009): (1) place illusion (i.e., the sense of being in the place); (2) plausibility illusion (i.e., the feeling that the scenario is actually taking place); (3) co-presence illusion (i.e., the sense of sharing the environment with other characters); and (4) social presence illusion (i.e., the feeling that a psychological link exists between oneself and the other characters). Despite the importance of understanding the specific relations between these four dimensions and realistic reactions to optimize the construction of immersive experiences, this issue remains poorly explored in VR and 360IV research.

Facing the needs of accessible immersive materials for clinicians, and an increased understanding of the relations between a sense of presence and individuals’ reactions, the current study had two aims. For the first time in the literature, to design and validate a 360IV that is capable of eliciting various psychological symptoms, namely: (1) fear of negative evaluation, (2) paranoid thoughts, (3) negative automatic thoughts, and craving for (4) alcohol and (5) nicotine. These five symptoms were selected for two main reasons. Firstly, they have all been shown to be significantly involved in the development and/or maintenance of psychological disorders such as social anxiety, paranoid delusion, depression, and substance use disorders (Field and Cox 2008; Freeman 2007; Rana et al. 2017; Reiss and McNally 1985). These disorders are highly prevalent in the general population with rates in the European population as follows: 7–13% for social anxiety (Furmark 2002), 10–15% for paranoid delusion (Eaton et al. 1991 as cited in Freeman et al. 2010), 12% for depression (World Health Organization 2017), 8.8% for alcohol use disorders (World Health Organization 2018), and 19% for smoking (Eurostat 2019). Therefore, such immersive material could be highly beneficial for clinicians who are used to face these disorders. Secondly, according to the transdiagnostic approach (Dalgleish et al. 2020), the five aforementioned symptoms have been found to be commonly present in various sets of other disorders including, for example, other types of anxiety disorders, psychosis or post-traumatic stress disorders (Castillo-Carniglia et al. 2019; Freeman et al. 2007; Koyuncu et al. 2019; Thaipisuttikul et al. 2014). Consequently, with the intention of being advantageous for clinicians, the resulting 360IV aims to address a large range of common psychological symptoms occurring in various disorders. The second aim was to explore the role of the four dimensions of presence (i.e., place illusion, plausibility illusion, co-presence illusion, and social presence illusion) in the occurrence of the five psychological symptoms.

To achieve these two aims, a 360IV was constructed that takes place in a bar representing an ordinary daily-life situation where all the aforementioned symptoms could be elicited. First, it was hypothesized that the 360IV would elicit fear of negative evaluation, paranoid thoughts, negative automatic thoughts and craving for alcohol and nicotine (i.e., hereafter termed as “state measures”) that, furthermore, reflect the individuals’ tendencies towards social anxiety, paranoia, depression, and alcohol and nicotine use (i.e., hereafter termed as “trait measures”). In particular, it was expected that (1) participants would report various levels of state measures; (2) there would be significant positive correlations between the state and related trait measures and; (3) self-reported craving for alcohol or nicotine after the immersion would increase in consumers. Secondly, the immersive properties of the 360IV were examined with expectations of sufficient levels of presence and low cybersickness. Finally, the specific relations between the four presence dimensions and state measures were explored.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

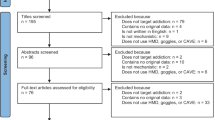

One hundred and fifty-eight participants (Table 1) were recruited through social networks between February 2020 and April 2021. A minimum of 154 participants was required based on an a priori power analysis performed using G*Power 3.1. (Faul et al. 2009) with alpha threshold of 0.01, power of 0.8 and an intermediate effect size of 0.25 for the correlation between state and trait measures.

The study was presented to the participants as the validation of a photorealistic immersive environment in the general population. Participants were aged between 18 and 50 years. Exclusion criteria included color blindness, brain injury or concussion with blackouts, epilepsy, severe migraine, cancer, hepatic disease, carbon intoxication, dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Participants with sever motion sickness (i.e., reporting being consistently nauseated and/or vomiting in at least two transport situations) were also excluded based on a modified version of the motion sickness susceptibility questionnaire (Golding 1998). This questionnaire is used to determine sensitivity to kinetosis, which is moderately correlated with a general tendency towards cybersickness (Kim et al. 2005).

2.2 Immersive environnements

2.2.1 Darius 360IV

The Darius Café 360IV (Fig. 1), filmed with a Vuze + 3D-360 VR camera (settings: 8 K, HD), lasts two and a half minutes and aims at reproducing a social, daily-life situation where the five above-mentioned symptoms might appear. The video represents the internal and external area of the Darius Café with 21 actors, comprising 8 groups (of 1–7 clients), and 1 waitress. All actors were instructed to behave naturally. In addition, depending on their group and places, certain actors received specific instructions about symptom triggers to include in their attitudes and behaviors. To elicit fear of negative evaluation and paranoid thoughts, certain actors were instructed to occasionally interact directly with the camera with gazes or smiles. To elicit negative automatic thoughts, certain actors were instructed to exhibit the joy of meeting people via hugs, kisses, smiles and exploding laughs. In addition, a couple of actors was asked to play the role of a romantic couple, and a young actor with an older actor was asked to present a mother–son relation. Finally, to elicit alcohol craving and nicotine craving, certain actors were instructed to smoke cigarettes outside the Darius Café and/or to drink beers. A detailed presentation of the stimuli and interactions between actors is available in Supplementary material 1. The camera was placed on a table with a wall behind so that the scene could be easily observed in its entirety. The sound of the video was not modified and resembled a large brouhaha where words were largely inaudible.

2.2.2 Familiarization immersion

The Calm Place application (Fig. 2, https://mimerse.com/products/calm-place/) was used to familiarize the participants with the Oculus Go. Calm Place is a virtual application developed by Mimerse in order to promote relaxation and mindfulness. The environment represents a campfire surrounded by nature (i.e., a lake, mountains, and forests) and small animals passing by (e.g., birds or butterflies). In order to prevent participants from relaxing, the sound of the application was turned off. Also, they were instructed to count the number of animals and report it after the familiarization immersion.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Participants’ information

By way of sampling information, participants completed questionnaires including sociodemographic and their general utilization of new technologies. Participants were also asked how often they use a smartphone, a computer, virtual reality, and play video games. In addition, they were asked to indicate how familiar they are with virtual reality on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 10 = “strongly agree”.

The Motion Sickness Susceptibility Questionnaire (MSSQ; Golding 1998) assesses the level of motion sickness experienced during various transportation-related activities and other activities. It contains 9 categories of possible experiences that elicit motion sickness (e.g., cars, buses, swings, funfairs). Each item is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “never” to 5 = “always”.

The Immersive Tendencies Questionnaire (ITQ; Witmer and Singer 1998) assesses one’s tendency to shut out external distractions in order to focus on different tasks in daily life. The French version (Robillard et al. 2002) contains 18 items where participants rate their level of agreement on a 7-point scale. Four dimensions are derived: focus (i.e., the tendency to maintain focus on current activities), involvement (i.e., the tendency to become involved in activities), emotion (i.e., the ease of feeling intense emotions evoked by the activity), and game (i.e., the tendency to play video games).

2.3.2 State anxiety

The State scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Y A; Spielberger et al. 1993) assesses current anxiety (20 items). All items are rated on a 4-point scale from 1 = “no’’ to 4 = “yes” (i.e., 2/3 = “rather no/yes”). Scores range from 20 to 80 with higher scores indicating greater anxiety.

2.3.3 Trait measures (i.e., general tendencies)

Social anxiety was assessed with the French version (Douillez et al. 2008) of the Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE; Watson and Friend 1969). The FNE consists of 30 items rated as 1 = “true” or 0 = “false” (e.g., “I am afraid others will not approve of me”). Scores range from 0 to 30 with higher scores indicating higher levels of social anxiety.

Paranoia was assessed with the French version (Della Libera et al. 2021) of the Green et al. Paranoid Thoughts Scale, part B (GPTS-B; Green et al. 2008). The GPTS-B consists of 16 items (e.g., “People have intended me harm”). Participants rate the intensity of such thoughts during the last month on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “totally”. Scores range from 16 to 80 with higher scores indicating a higher level of paranoia.

Severity of depressive symptoms experienced during the last 7 days were assessed with the French version (Fuhrer and Rouillon 1989) of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression (CES-D; Radloff 1977). The CES-D consists of 20 items rated on a scale ranging from 0 = “never” to 3 = “frequently, all the time”. Scores range from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating higher symptom severity. In addition, a score of 16 or above indicates the presence of depressive symptomatology.

Alcohol consumption was assessed with the French version (Gache et al. 2005) of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al. 1993). The AUDIT includes 10 multiple-choice items measuring alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence and alcohol-related problems. A score ranging from 0 to 40 is obtained by adding the score of each item. A score above 10 indicates an at-risk consumption (Fleming et al. 1991).

Nicotine consumption was assessed with a series of questions where participants indicated whether they were smokers, former smokers or non-smokers. The average number of cigarettes smoked par day, the frequency and duration of their addiction were asked for smokers and former smokers. Former smokers were also asked to indicate when they stopped smoking, the number of years they smoked, and the average number of cigarettes they smoked each day. These questions allowed to identify the smoking pattern of the current and former smokers.

2.3.4 State measures (i.e., symptoms occurring during the immersion)

Fear of negative evaluation was assessed with an adapted version of the Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE; Watson and Friend 1969) constructed for the present study. In particular, FNE items were selected by CDL, JS, AW each time a state formulation was possible and transformed into state statements related to actors’ negative evaluations (e.g., “I am afraid that people will find fault with me” was transformed in “I was afraid that people find something wrong with me”). The state version of the FNE (S-FNE) consists of 14 items rated as 1 = “true” or 0 = “false”. Scores range from 0 to 14 with higher scores indicating higher levels of state social anxiety. The internal consistency of the S-FNE in this sample is acceptable (McDonald’s omega: 0.70).

Paranoid thoughts were assessed using the French translation (Della Libera et al. 2021) of the State Social Paranoia Scale (SSPS; Freeman et al. 2007). The SSPS consists of 20 items, with 10 items assessing negative interpretations about actors’ intentions interpreted as paranoid thoughts (e.g., “Someone was hostile towards me”) and 10 other items describing positive or neutral interpretations about actors’ intentions (e.g., “Someone was friendly towards me”; “Everyone was neutral towards me”). Participants rated the extent to which they agree with the sentence on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “do not agree” to 5 = “totally agree”. Higher scores on the 10 paranoia items indicate higher levels of paranoid ideation.

Negative automatic thoughts were assessed with an adapted version of the French version of the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ; Lebreuilly and Alsaleh 2019). The ATQ is traditionally used to assess negative and positive cognitions in the past week. For the present study, the items were adapted to assess their thoughts during the 360IV. In particular, participants were asked to indicate whether the 18 thoughts had crossed their mind during the immersion using a “true” or false” scale (e.g., “I’m so disappointed in myself”). The positive automatic thinking (ATQP) score is equal to the sum of the first 10 items and the negative automatic thinking (ATQN) score is equal to the sum of the last 8 items. In that the ATQN score is considered to be a measure of depressive thoughts (Harrington and Blankenship 2002), only this measure was taken into account in the present study. The internal consistency of the ATQP and ATQN in this sample is good (McDonald’s omega: 0.80 and 0.82, respectively).

Alcohol and nicotine cravings were each assessed before and after the immersion with four visual analog scales (VAS; Kreusch et al. 2017) from 0 to 100. VAS before immersion evaluated (1) the expectancy of positive reinforcements (i.e., “Having a drink/smoking a cigarette would make things just perfect”), (2) the strength of craving (i.e., “How strong is your craving to drink alcohol/to smoke”), (3) the intent to consume (i.e., “If I could drink alcohol now/smoke now, I would have a drink/have a smoke”), and (4) the lack of control (i.e., “It would be hard to turn down a drink/a cigarette right now”). The VAS after the immersion was the same as before the immersion except that it was adapted in order to emphasize the degree of craving felt during the virtual immersion (e.g., “During the immersion, drinking a glass of alcohol/smoking a cigarette would have made things just perfect”). For both alcohol and nicotine craving, two craving scores were calculated by averaging the four pre-immersion or the four post-immersion VAS.

2.3.5 Virtual reality

The four presence dimensions were assessed with a 16-item questionnaire in French (Table 2, Wagener and Simon, in preparation) that is consistent with Slater’s (2009) and Biocca and colleagues’ (2003) theoretical conceptions. Participants replied on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = “totally disagree” to 7 = “totally agree”. The four dimensions included “place illusion” (i.e., the sense of being in the place); “plausibility illusion” (i.e., the feeling that the scenario is actually taking place); “copresence illusion” (i.e., the sense of sharing the environment with other characters); and “social presence illusion” (i.e., the feeling that a psychological link exists between oneself and the other characters). Scores of each dimension range from 4 to 28 with higher scores indicating higher sense of presence. The psychometric qualities of this questionnaire are satisfactory (confirmatory factorial analysis: χ2/dl = 167.63/98 = 1.71; RMSEA = 0.067; SRMR = 0.06; CFI = 0.996; TLI = 0.995, McDonald’s omega: ωplace = 0.89, ωplausibility = 0.88, ωcopresence = 0.80, ωsocial = 0.81).

Cybersickness was assessed with the French version (Bouchard et al. 2011) of the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ; Kennedy et al. 1993). The SSQ consists of 16 items distributed across two subscales that assess nausea (SSQN) and oculomotor symptoms (SSQOM). Participants reply on 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “not at all” to 3 = “severely” regarding the extent to which the symptom is present. Scores range from 0 to 24 for each subscale with higher scores indicating higher levels of cybersickness.

2.4 Procedure

The study is composed of two phases including an online questionnaire session and a face-to-face meeting (Fig. 3). During the online questionnaire session, and after providing an initial online informed consent, participants completed the sociodemographic questionnaire, the MSSQ, the ITQ, the questionnaire on the use of new technologies, the GPTS-B, the FNE, the CES-D, the AUDIT and the questions concerning nicotine consumption. After this first measurement, participants were invited between 3 and 15 days on the campus of the University for the second phase. After providing a second-written informed consent, the familiarization immersion phase took place and participants were immersed for 2 min with the instruction to count the number of animals. After the familiarization immersion phase, participants completed the STAI-Y A, the SSQ, the pre-immersion alcohol and nicotine craving. Then, the immersion phase started, and participants were given the following instructions: “You are now going to be immersed in a bar for two and a half minutes. Persons and objects will be present around you. Please, pay attention to them and just behave as you would in a similar situation”. Finally, participants were instructed to complete the post-immersion questionnaires by referring to what happened during the immersion and were given the alcohol and nicotine craving, the SSQ, the S-FNE, the ATQP and ATQN, the SSPS, and the questionnaire of presence. All immersions took place using the wireless Oculus Go headset (Panel Type: 5.5″ Single Fast-Switch LCD 2560 × 1440; 1280 × 1440 pixels per eye; Refresh Rate: 60–72 Hz; FOV: 110°).

Schematic representation of the procedure. MSSQ = Motion Sickness Susceptibility Questionnaire, ITQ = Immersive Tendencies Questionnaire, GPTS-B = Green et al. Paranoid Thoughts Scale—part B, FNE = Fear of negative evaluation, CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression, STAI-Y A = State scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, SSQ = Simulator Sickness Questionnaire. S-FNE = State Fear of Negative Evaluation, ATQ = Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire

The study was approved by the local ethics committee and was conducted following the ethical standards as described in the Declaration of Helsinki (1964).

2.5 Statistical analyses

Analyses were carried out using JAMOVI 1.8.2 (The jamovi project 2021) and R (Rosseel 2012).

First, the distributions of the state measures including fear of negative evaluation, paranoid thoughts, negative automatic thoughts, as well as post-immersion craving for alcohol and nicotine were presented. For craving, only the results for alcohol drinkers (AUDIT score > 0), current smokers, and former smokers were presented. In addition, data were grouped into intervals in order to ease readability. Thereafter, the relationship between state and trait measures was calculated using one-tail test Kendall’s correlations. The correction of Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) for multiple testing was applied in order to identify significant positive correlations. In the case of craving, only results for alcohol drinkers and current smokers were presented. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to compare pre- and post-immersion alcohol craving among alcohol drinkers and nicotine craving among current smokers. Rank biserial correlation was used as a measure of effect size.

Then, the immersive properties of the 360IV were examined. Descriptive statistics for cybersickness and the four dimensions of presence were presented. To test whether the 360IV induces cybersickness, one-tail test Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed on both the SSQN and SSQOM subscales. Rank biserial correlations were used as a measure of effect size.

Finally, in order to explore the relations between the four presence dimensions and the five symptoms, four exploratory multiple quasi-Poisson regression analyses with state measures as the dependent variable, and the four dimensions of presence as independent variables, were performed. The quasi-Poisson regression was chosen due to the nature of the data distributions. Indeed, quasi-Poisson regression recognizes the relative rarity of events, which allows for efficient modelling of the non-linear nature of the data. This is particularly interesting when studying psychological symptoms in the general population. Given that the Poisson regression model assumes that the data are equally dispersed, meaning that the conditional variance equals the conditional mean, a correction for over-dispersion in case of violation of this condition (Green 2021) was considered. Odd ratios (expβ) were used as a measure of effect size.

3 Results

3.1 Five symptoms’ occurrence

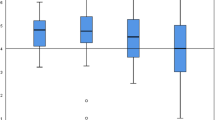

Based on the S-FNE, SSPS, ATQN scores, and craving VAS distributions (Fig. 4), participants reported various levels of fear of negative evaluation, paranoid thoughts, negative automatic thoughts and craving among alcohol and nicotine consumers during the immersion. These results indicate that the 360IV was able to elicit emotional reactions and thoughts.

Thereafter, Kendall’s correlations (Table 3) between state and trait measures were performed. After applying a correction for multiple testing (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995; p ≤ 0.03), results revealed small significant positive correlations between each state and related trait measures (i.e., S-FNE and FNE; SSPS and GPTS-B; ATQN and CES-D; Post-immersion alcohol craving and AUDIT) except for post-immersion nicotine craving and number of cigarettes smoked each day (\(r_{T}\) = − 0.07, p = 0.63). Taken together, these results suggest that participants’ reactions during the immersion were significantly predicted by their own tendencies towards social anxiety, paranoia, depression and alcohol consumption.

Finally, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (Fig. 5a, b) revealed an increase of alcohol craving, after immersion, among alcohol drinkers (W = 2320; p < 0.001, = \(r_{rb}\) − 0.38) as well as an increase of nicotine craving among smokers (W = 93; p = 0.032; \(r_{rb}\) − 0.43).

3.2 Immersive properties

Based on the descriptive statistics concerning immersive properties (Table 4), it was observed that the 360IV elicited various levels of the four illusions of presence with ranges varying from the near minimum to the maximum scores, with medians ranging from 13 (i.e., social presence) to 23 (i.e., place illusion). Regarding cybersickness, results revealed overall low scores ranging from 0 to 12 before the immersion and 0 to 17 after the immersion, with medians ranging from 1 to 2. To test the 360IV’s impact on cybersickness, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests on both SSQN and SSQOM subscales revealed a significant increase for SSQN but not for SSQOM.

3.3 Relations between symptoms and presence dimensions

A multiple quasi-Poisson regression analysis (Table 5) was computed on each state measure except for nicotine craving due to the inconsistent distribution. Results revealed that place illusion negatively predicted S-FNE, SSPS and ATQN. Moreover, copresence positively predicted ATQN while social presence positively predicted S-FNE and SSPS.

4 Discussion

In a period characterized by increases in mental healthcare requests (Robinson et al. 2021), it seems worthwhile to have novel, efficient and validated transdiagnostic tools available. In this context, the first aim of the present study was to develop and validate a 360IV designed to assess five core symptoms: social anxiety (i.e., fear of negative evaluation), paranoia (i.e., paranoid thoughts), depression (i.e., negative automatic thoughts) and two substance use disorders (i.e., craving for alcohol and nicotine). In addition, in order to increase the understanding of the important components of immersion, the second aim of the present study was to explore the role of four dimensions of presence in the occurrence of the five psychological symptoms. Overall, results confirmed the study’s hypotheses. Beginning with the validation of the 360IV, results revealed that the 360IV was able to elicit various levels of the five psychological symptoms. In addition, all symptoms, except post-immersion craving for nicotine, were significantly predicted by the participants’ general tendencies (i.e., trait) towards these symptoms. Alcohol and nicotine craving scores were also significantly higher at the end than at the beginning of the immersion in users (i.e., alcohol drinkers and smokers). Thereafter, the 360IV immersive properties were found to be adequate, with globally low levels of cybersickness and wide ranges of levels for all dimensions of presence. Finally, exploratory regression analyses of each symptom on the different dimensions of presence revealed that not all these dimensions were equally related to the different symptoms.

Regarding the occurrence of the five specific symptoms, the results are in line with previous studies in non-clinical samples that found it possible to use a 360IV to elicit symptoms of social anxiety (Barreda-Ángeles et al. 2020; Holmberg et al. 2020) or paranoia (Della Libera et al. 2021). They are, however, novel for negative automatic thoughts and for craving (excepted in VR studies; Bordnick and Washburn 2019; Segawa et al. 2020). Results also revealed a small albeit significant, positive correlations between trait and state measures. Although comparisons must be carried out with caution due to different designs and measures, these results are also similar to those from studies on social anxiety (i.e., correlations ranging from 0.40 to 0.53; Sigurvinsdottir et al. 2021) or paranoia (i.e., correlations ranging from 0.24 to 0.51; Della Libera et al. 2021; Freeman et al. 2007). It is worth mentioning that several significant correlations were also found between different symptoms (e.g., state fear of negative evaluation with trait paranoia and depression). Such findings are in accordance with a transdiagnostic approach of psychopathology (Dalgleish et al. 2020; Philippot et al. 2019) as well as with the well-known comorbidities between the symptoms (Castillo-Carniglia et al. 2019; Freeman et al. 2007; Koyuncu et al. 2019). However, they raise the questions of the 360IV discriminant validity which will need to be addressed in further studies. Despite this, these results contribute to validating the use of the 360IV for the assessment of the five symptoms while taking into account differences in respective constructs. Besides the five symptoms, these results also validate the possibility to use the 360IV for the assessment of multiple transdiagnostic symptoms. Ultimately, this approach aims at providing clinicians with valid and accessible material for a larger number of individuals and difficulties. It therefore meets the call for a greater variety of tests and stimuli among immersive technologies (Pandita and Won 2020) and for the validation of more assessment versus treatment tools (Bell et al. 2020; Serrano et al. 2019). Further research is needed to explore the extent of symptoms that can be explored with the use of 360IV. This would contribute to the promising emergence of new ecological and standardized assessment tools. The present findings also confirm the adequate immersive properties of the 360IV in that, overall, low levels of cybersickness and moderate levels of all dimensions of presence were observed. Beginning with cybersickness, results revealed a slight increase of nausea symptoms after immersion (i.e., median increase from 0 to 1 on a scale ranging from 0 to 24) but not for oculomotor symptoms. These results are consistent with previous 360IV studies that have revealed low degree of cybersickness (Chirico and Gaggioli 2019; Della Libera et al. 2021). They are also coherent with the visual and vestibular conflict explanation of cybersickness, which posits that these negative effects result from a physical movement perception of the eyes in the absence of the perception of physical movements by the body (Pan and Hamilton 2018). Accordingly, in that 360IVs are deprived of responsiveness and moving possibilities, they may represent a globally safe immersive experience option. Still, regarding the slight increase of nausea symptoms, one interesting question regards the possibility that these symptoms are more a reflection of the participants’ emotional reactions rather than being related to a real induction of nausea. Indeed, many studies have highlighted specific patterns of bodily sensations elicited by different emotions (Jung et al. 2017; Nummenmaa et al. 2014). These physiological responses could be similar in nature to those experienced in the context of the cybersickness and which contaminate this measure. This hypothesis needs to be examined in future studies.

Results regarding presence also confirm results from previous studies that have found that the 360IV is able to elicit the feeling of being present into the immersive environment (Chirico and Gaggioli 2019; Narciso et al. 2019). It is noteworthy that, to date, among the few studies comparing VR and 360IV in terms of presence (Brivio et al. 2020; Tarnawski 2017; Yeo et al. 2020), the only one to find a superiority in favor of VR (Yeo et al. 2020) was also the only one to compare a responsive VR environment (i.e., participants were allowed to physically move around) with a non-interactive 360IV environment (i.e., no movements were allowed). This may underline the particular importance of responsiveness for place and plausibility illusions in immersive technologies. Interestingly, our 360IV was also able to elicit various levels of copresence illusions and social presence. This is a new finding in the literature and suggests that the simple presence of character with passive social interactions (i.e., occasional gazes and/or smiles) is sufficient to allow for the feeling of being with others and even sometimes, a feeling of being in relation with these others. Compared to VR, one important advantage of the 360IV is its ability to provide photorealistic images but also realistic behaviors (e.g., breathing, walking, postures) which are recognized as strong predictors of social presence (Oh et al. 2018). Therefore, in the context of passive social interactions (i.e., absence of complete dialogue with the user), one could expect an advantage of the 360IV over VR in terms of copresence/social presence, whereas there may be an advantage of VR over the 360IV in terms of place illusion. This hypothesis requires more direct and detailed examination and would lead to a better guidance for optimal immersive technology selection.

Finally, many studies have emphasized the importance of presence in order to elicit realistic user behaviors (Diemer et al. 2015; Parsons and Rizzo 2008). However, few of these studies have focused on identifying the dimensions that seem to contribute most to the occurrence of these behaviors. This study, as well as a few others (Felnhofer et al. 2019; Gamito et al. 2014; Price et al. 2011; Simon et al. 2020), is part of this approach. In particular, the psychological relationship that users have with avatars (i.e., social presence) seems to be elements that should not be overlooked in eliciting cognitions involved in social anxiety and paranoia. This is consistent with the intrinsic interpersonal nature of social anxiety and paranoia which can be respectively defined as the pervasive fears of other’s negative evaluation (APA 2013) and malevolent intention (Freeman and Garety 2000). The induction of negative automatic thoughts would rather be related to being surrounded by individuals expressing positive emotions. Given the social component of fear of negative evaluation and paranoid or depressive thoughts, the use of the 360IV seems particularly appropriate as it faithfully reproduces the complexity of social interactions which are the most consistent triggers copresence (Bente et al. 2008; Pan et al. 2008; Oh et al. 2018; von der Pütten et al. 2010). Conversely, the expression of cognitive symptoms was associated with negative place illusion. It is possible that the induced thoughts interfere with the cognitive processes that allow the person to project into the virtual environment. Another explanation could be that participants with intermediate or high levels of symptoms are psychologically distancing themselves from their current experience in order to manage their cognitions, leading them to feel less the place illusion. Thus, studies must be specifically conducted to identify the dimensions of presence that contribute most to various emotional and cognitive states. This will help to create immersive environments that promote them beyond the care given to purely technological aspects (i.e., immersion).

This study has several limitations. A first limitation is the lack of a control condition including a neutral 360IV to guarantee that the five psychological symptoms were effectively triggered by Darius Café (i.e., versus the effect of time of the day). This limitation was partly alleviated by the fact that all state measures referred, to some extent, to the 360IV scenario. In particular, the items concerning paranoid thoughts and fear of negative evaluation directly concerned the intentions or evaluations of the actors from the scenario, leading these symptoms to be hardly attributable to external factors. However, these references to the scenario may not be sufficient to exclude the effect of external factors, especially on the occurrence of negative automatic thoughts and nicotine craving as would have allowed a control condition. It is worth mentioning that such a control condition has been included in several VR studies which confirm the superiority of smoking related content versus non-smoking related content in eliciting the craving (Bordnick et al. 2004; García-Rodriguez et al. 2013).

Secondly, a non-clinical sample was chosen to guarantee the safety of participants exposed to a new kind of material. On the one hand, this limits the validity of the 360IV to non-clinical symptoms. On the other hand, the 360IV’s ability to elicit mild symptoms in a non-clinical population suggests that the 360IV could also be appropriate to elicit more severe symptoms in clinical populations. One important further step is therefore to validate the 360IV in clinical samples in terms of social anxiety, paranoia, depression and consumption disorders. Second, the sub-sample of smokers was relatively small (i.e., thirty-one participants), which limits the interpretation of the results. Finally, it deserves mentioning that participants were recruited during the COVID-19 pandemic and, particularly, when all bars were closed and that this may have affected the results. For instance, this may have exacerbated the occurrence of symptoms in those participants who were more isolated. However, the validity of the results should not have been affected as the symptoms observed during the immersion reflected the possible variation in participants’ tendencies due to the pandemic situation.

The current findings present several important clinical and experimental perspectives, some of which are interrelated. First, the results support the use of immersive experiences (and especially via 360IVs) for the assessment of multiple transdiagnostic symptoms. In particular, our 360IV presented a good level of validity and thus could be used in future research designs and/or clinical settings to assess the five symptoms in a new, ecological, and standardized way. From an experimental perspective, clinical protocols using our 360IV should also be pursued to offer guidelines in regards to its use in clinical settings. Eventually, such validations might lead to possible gains of time and money—by decreasing the length of clinical interventions—which is not insignificant for both clinicians and researchers in psychology. Actually, this tips the scale in favor of the benefits—rather than costs—of the 360IV. Second, the adoption of a multidimensional approach of presence that distinguishes between the four dimensions revealed the distinct importance of these dimensions related to the observed emotional and cognitive reactions. This underlines the importance of investigating the separate dimensions of presence in relation to individuals’ behaviors. Further research focusing on the implication of these dimensions on psychopathological symptoms may help future clinicians and researchers to better design their immersive environments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

References

Pandita S, Won AS (2020) Clinical applications of virtual reality in patient-centered care. Technology and health. Academic Press, Cambridge, pp 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-816958-2.00007-1

APA (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington

Barreda-Ángeles M, Aleix-Guillaume S, Pereda-Baños A (2020) Users’ psychophysiological, vocal, and self-reported responses to the apparent attitude of a virtual audience in stereoscopic 360°-video. Virtual Real 24:289–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-019-00400-1

Bell IH, Nicholas J, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Thompson A, Valmaggia L (2020) Virtual reality as a clinical tool in mental health research and practice. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 22:169–177. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.2/lvalmaggia

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 57:289–300. https://doi.org/10.2307/2346101

Bente G, Rüggenberg S, Krämer NC, Eschenburg F (2008) Avatar-mediated networking: increasing social presence and interpersonal trust in net-based collaborations. Hum Commun Res 34:287–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2008.00322.x

Biocca F, Harms C, Burgoon JK (2003) Toward a more robust theory and measure of social presence: review and suggested criteria. Presence: Teleoperators Virtual Environ 12:456–480. https://doi.org/10.1162/10547460332276270

Bordnick PS, Washburn M (2019) Virtual environments for substance abuse assessment and treatment. Virtual reality for psychological and neurocognitive interventions. Springer, New York, pp 131–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9482-3_6

Bordnick PS, Graap KM, Copp H, Brooks J, Ferrer M, Logue B (2004) Utilizing virtual reality to standardize nicotine craving research: a pilot study. Addict Behav 29(9):1889–1994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.008

Bouchard S, Robillard G, Renaud P, Bernier F (2011) Exploring new dimensions in the assessment of virtual reality induced side effects. J Comp Inf Technol 1:20–32

Brivio E, Serino S, Cousa EN, Zini A, Riva G, De Leo G (2020) Virtual reality and 360° panorama technology: a media comparison to study changes in sense of presence, anxiety, and positive emotions. Virtual Real 25:303–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-020-00453-7

Castillo-Carniglia A, Keyes KM, Hasin DS, Cerdá M (2019) Psychiatric comorbidities in alcohol use disorder. Lancet Psychiatry 6:1068–1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30222-6

Chirico A, Gaggioli A (2019) When virtual feels real: comparing emotional responses and presence in virtual and natural environments. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 22:220–226. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0393

Cieślik B, Mazurek J, Rutkowski S, Kiper P, Turolla A, Szczepańska-Gieracha J (2020) Virtual reality in psychiatric disorders: a systematic review of reviews. Complement Ther Med 52:102480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102480

Dalgleish T, Black M, Johnston D, Bevan A (2020) Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: current status and future directions. J Consul Clin Psychol 88:179. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000482

Della Libera C, Larøi F, Raffard S, Quertemont E, Laloyaux J (2020) Exploration of the paranoia hierarchy in the general population: evidence of an age effect mediated by maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 25:387–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2020.1824868

Della Libera C, Quertemont E, Laloyaux J, Thonon B, Larøi F (2021) Using 360° immersive videos to assess paranoia in a non-clinical population. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 26:357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2021.1956885

Dellazizzo L, Potvin S, Luigi M, Dumais A (2020) Evidence on virtual reality-based therapies for psychiatric disorders: meta-review of meta-analyses. J Med Internet Res 22:e20889. https://doi.org/10.2196/20889

Diemer J, Alpers GW, Peperkorn HM, Shiban Y, Mühlberger A (2015) The impact of perception and presence on emotional reactions: a review of research in virtual reality. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00026

Douilliez C, Baeyens C, Philippot P (2008) Validation d’une version francophone de l’Echelle de Peur de l’Evaluation Negative (FNE) et de l’Echelle d’Evitement et de Détresse Sociale (SAD). Revue Francophone De Clinique Comportementale Et Cognitive 13:1–11

Emmelkamp PM, Meyerbröker K, Morina N (2020) Virtual reality therapy in social anxiety disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 22:32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-020-01156-1

Eurostat (2019) Daily smokers of cigarettes by sex, age and educational attainment level. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/hlth_ehis_sk3e/default/table?lang=en

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG (2009) Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Resh Methods 41:1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Felnhofer A, Hlavacs H, Beutl L, Kryspin-Exner I, Kothgassner OD (2019) Physical presence, social presence, and anxiety in participants with social anxiety disorder during virtual cue exposure. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 22:46–50. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0221

Field M, Cox WM (2008) Attentional bias in addictive behaviours: a review of its development, causes, and consequences. Drug Alcohol Depend 97:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.030

Fleming MF, Barry KL, MacDonald R (1991) The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in a college sample. Int J Addict 26:1173–1185. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089109062153

Freeman D (2007) Suspicious minds: the psychology of persecutory delusions. Clin Psychol Rev 27:425–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.10.004

Freeman D, Garety P (2000) Comments on the content of persecutory delusions: does the definition need clarification? BJ Psych 39:407–414. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466500163400

Freeman D, Pugh K, Green C, Valmaggia L, Dunn G, Garety P (2007) A measure of state persecutory ideation for experimental studies. J Nerv Ment Dis 195:781–784. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e318145a0a9

Freeman D, Pugh K, Vorontsova N, Antley A, Slater M (2010) Testing the continuum of delusional beliefs: an experimental study using virtual reality. J Abnorm Psychol 119(1):83–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017514

Fuhrer R, Rouillon F (1989) La version française de l’échelle CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale). Description et traduction de l’échelle d’autoévaluation. Psychiatr Et Psychobiol 4:163–166. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0767399x00001590

Furmark T (2002) Social phobia: overview of community surveys. Acta Psychiatr Scand 105:84–93. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r103.x

Gache P, Michaud P, Landry U, Accietto C, Arfaoui S, Wenger O, Daeppen JB (2005) The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screening tool for excessive drinking in primary care: reliability and validity of a French version. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:2001–2007. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.alc.0000187034.58955.64

Gamito P, Oliveira J, Baptista A, Morais D, Lopes P, Rosa P, Santos N, Brito R (2014) Eliciting nicotine craving with virtual smoking cues. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 17:556–561. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0329

García-Rodríguez O, Secades-Villa R, Flórez-Salamanca L, Okuda M, Liu SM, Blanco C (2013) Probability and predictors of relapse to smoking: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend 132(3):479–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.008

Geraets C, van der Stouwe E, Pot-Kolder R, Veling W (2021) Advances in immersive virtual reality interventions for mental disorders: a new reality? Curr Opin Psychol 41:40–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.02.004

Golding JF (1998) Motion sickness susceptibility questionnaire revised and its relationship to other forms of sickness. Brain Res Bull 47:507–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00091-4

Green JA (2021) Too many zeros and/or highly skewed? A tutorial on modelling health behaviour as count data with Poisson and negative binomial regression. Health Psychol Behav Med 9:436–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2021.1920416

Green CEL, Freeman D, Kuipers E, Bebbington P, Fowler D, Dunn G, Garety PA (2008) Measuring ideas of persecution and social reference: the Green et al. Paranoid Thought Scales (GPTS). Psychol Med 38:101–111. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707001638

Harrington JA, Blankenship V (2002) Ruminative thoughts and their relation to depression and anxiety. J Appl Soc Psychol 32:465–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00225.x

Higuera-Trujillo JL, Maldonado JLT, Millán CL (2017) Psychological and physiological human responses to simulated and real environments: a comparison between Photographs, 360 Panoramas, and Virtual Reality. Appl Ergon 65:398–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2017.05.006

Holmberg TT, Eriksen TL, Petersen R, Frederiksen NN, Damgaard-Sørensen U, Lichtenstein MB (2020) Social anxiety can be triggered by 360-degree videos in virtual reality: a Pilot Study exploring fear of shopping. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw 23:495–499. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0295

Jung WM, Ryu Y, Lee YS, Wallraven C, Chae Y (2017) Role of interoceptive accuracy in topographical changes in emotion-induced bodily sensations. PloS one 12:e0183211

Kennedy RS, Lane NE, Berbaum KS, Lilienthal MG (1993) Simulator sickness questionnaire: an enhanced method for quantifying simulator sickness. Int J Aviat Psychol 3:203–220. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327108ijap0303_3

Kim YY, Kim HJ, Kim EN, Ko HD, Kim HT (2005) Characteristic changes in the physiological components of cybersickness. J Psychophysiol 42:616–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00349.x

Kim IY, Kim SI, Shen DF (2008) Development and verification of an alcohol craving–induction tool using virtual reality: craving characteristics in social pressure situation. CyberPsychol Behav 11:302–309. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0149

Kittel A, Larkin P, Cunningham I, Spittle M (2020) 360 virtual reality: a SWOT analysis in comparison to virtual reality. Front Psychol 11:563474. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.563474

Koyuncu A, İnce E, Ertekin E, Tükel R (2019) Comorbidity in social anxiety disorder: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Drugs Context 8:1–13. https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.212573

Kreusch F, Billieux J, Quertemont E (2017) Alcohol-cue exposure decreases response inhibition towards alcohol-related stimuli in detoxified alcohol-dependent patients. Psychiatry Res 249:232–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.019

Lebreuilly R, Alsaleh M (2019) Élaboration d’un questionnaire court de pensées automatiques positives et négatives (ATQ-18-Fr) auprès d’étudiants français [Development of a short questionnaire of positive and negative automatic thoughts (ATQ-18-Fr) with French students]. J Ther Comport Cogn 29:132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcc.2019.01.003

Lee JS, Namkoong K, Ku J, Cho S, Park JY, Choi YK, Kim J-J, Kim IY, Kim SI, Jung Y-C (2008) Social pressure-induced craving in patients with alcohol dependence: application of virtual reality to coping skill training. Psychiatry Investig 5:239–243. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2008.5.4.239

Narciso D, Bessa M, Melo M, Coelho A, Vasconcelos-Raposo J (2019) Immersive 360° video user experience: impact of different variables in the sense of presence and cybersickness. Univers Access Inf Soc 18:77–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-017-0581-5

Nummenmaa L, Glerean E, Hari R, Hietanen JK (2014) Bodily maps of emotions. PNAS 111:646–651. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321664111

Oh CS, Bailenson JN, Welch GF (2018) A systematic review of social presence : definition, antecedents, and implications. Front Robot AI 5:114. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2018.00114

Pan X, Gillies M, Slater M (2008) The impact of avatar blushing on the duration of interaction between a real and virtual person. In: Presence 2008: the 11th annual international workshop on presence, pp 100–106. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/125118/

Pan X, Hamilton AFdC (2018) Why and how to use virtual reality to study human social interaction: the challenges of exploring a new research landscape. Br J Psychol 109:395–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12290

Parsons TD, Rizzo AA (2008) Initial validation of a virtual environment for assessment of memory functioning: virtual reality cognitive performance assessment test. CyberPsychol Behav 11:17–25. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.9934

Philippot P, Bouvard M, Baeyens C, Dethier V (2019) Case conceptualization from a process-based and modular perspective: rationale and application to mood and anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Psychother 26(2):175–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2340

Price M, Mehta N, Tone EB, Anderson PL (2011) Does engagement with exposure yield better outcomes? Components of presence as a predictor of treatment response for virtual reality exposure therapy for social phobia. J Anxiety Disord 25:763–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.004

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1:385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

Rana M, Sthapit S, Sharma VD (2017) Assessment of automatic thoughts in patients with depressive illness at a Tertiary Hospital in Nepal. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 56:248–255. https://doi.org/10.31729/jnma.3101

Reiss S, McNally RJ (1985) Expectancy model of fear. In: Reiss S, Bootzin R (eds) Theoretical issues in behaviour therapy. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 107–121

Riva G, Serino S (2020) Virtual reality in the assessment, understanding and treatment of mental health disorders. Psychol Med 47:2393–2400. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171700040X

Riva G, Mantovani F, Capideville CS, Preziosa A, Morganti F, Villani D, Gaggioli A, Botella C, Alcañiz M (2007) Affective interactions using virtual reality: the link between presence and emotions. CyberPsychol Behav 10:45–56. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9993

Robillard G, Bouchard S, Renaud P, Cournoyer LG (2002) Validation canadienne-française de deux mesures importantes en réalité virtuelle: l’Immersive Tendencies Questionnaire et le Presence Questionnaire. In: Poster presented at the 25e congrès annuel de la Société Québécoise pour la Recherche en Psychologie (SQRP), Trois-Rivières

Robinson E, Sutin AR, Daly M, Jones A (2021) A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord 296:567–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098

Rosseel Y (2012) Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48(2):1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rus-Calafell M, Garett P, Sason E, Craig TJ, Valmaggia LR (2018) Virtual reality in the assessment and treatment of psychosis: a systematic review of its utility, acceptability and effectiveness. Psychol Med 48:362–391. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717001945

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Amundsen A, Grant M (1993) Alcohol consumption and related problems among primary health care patients: WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-I. Addiction 88:349–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00822.x

Scheveneels S, Boddez Y, Van Daele T, Hermans D (2019) Virtually unexpected: no role for expectancy violation in virtual reality exposure for public speaking anxiety. Front Psychol 10:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02849

Schubert TW, Friedmann F, Regenbrecht HT (1999) Decomposing the sense of presence: factor analytic insights. In: 2nd international Workshop on Presence (vol. 1999)

Schutte NS, Stilinović EJ (2017) Facilitating empathy through virtual reality. Motiv Emot 41:708–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9641-7

Segawa T, Baudry T, Bourla A, Blanc JV, Peretti CS, Mouchabac S, Ferreri F (2020) Virtual reality (VR) in assessment and treatment of addictive disorders: a systematic review. Front Neurosci 13:1409. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.01409

Serrano B, Botella C, Wiederhold BK, Baños RM (2019) Virtual reality and anxiety disorders treatment: evolution and future perspectives. In: Rizzo S, Bouchard S (eds) Virtual reality for psychological and neurocognitive interventions. Springer, New York, pp 47–84

Sigurvinsdottir R, Soring K, Kristinsdottir K, Halfdanarson S, Johannsdottir K, Vilhjalmsson H, Valdimarsdottir H (2021) Social anxiety, fear of negative evaluation, and distress in a virtual reality environment. Behav Change 38:109–118. https://doi.org/10.1017/bec.2021.4

Simon J, Etienne A-M, Bouchard S, Quertemont E (2020) Alcohol craving in heavy and occasional alcohol drinkers after cue exposure in a virtual environment: the role of the sense of presence. Front Hum Neurosci 14:124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2020.00124

Slater M (2003) A note on presence terminology. Presence Connect 3:1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.01409

Slater M (2009) Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 364:3549–3557. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0138

Slater M, Wilbur S (1997) A framework for immersive virtual environments (FIVE): speculations on the role of presence in virtual environments. Presence: Teleoperators Virtual Environ 6:603–616. https://doi.org/10.1162/pres.1997.6.6.603

Spielberger CD, Bruchon-Schweitzer M, Paulhan P (1993) Inventaire d'anxiété état-trait Forme Y (STAI-Y). Les Editions du Centre de Psychologie Appliquée. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0078881

Stupar-Rutenfrans S, Ketelaars LE, van Gisbergen MS (2017) Beat the fear of public speaking: mobile 360 video virtual reality exposure training in home environment reduces public speaking anxiety. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 20:624–633. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0174

Tarnawski M (2017) Treating presence as a noun—insights obtained from comparing a VE and a 360 video. SIGRAD 143:9–16

Thaipisuttikul P, Ittasakul P, Waleeprakhon P, Wisajun P, Jullagate S (2014) Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 10:2097–2103. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S72026

The jamovi project (2021). jamovi (Version 1.6) [Computer Software]. https://www.jamovi.org

von der Pütten AM, Krämer NC, Gratch J, Kang S-H (2010) “It doesn’t matter what you are!” Explaining social effects of agents and avatars. Comput Hum Behav 26:1641–1650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.012

Watson D, Friend R (1969) Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol 33:448–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0027806

Witmer BG, Singer MJ (1998) Measuring presence in virtual environments: a presence questionnaire. Presence 7:225–240. https://doi.org/10.1162/105474698565686

World Health Organization (2017) Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. https://repository.gheli.harvard.edu/repository/11487/

World Health Organization (2018) Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274603

Yeo NL, White MP, Alcock I, Garside R, Dean SG, Smalley AJ, Gatersleben B (2020) What is the best way of delivering virtual nature for improving mood? An experimental comparison of high definition TV, 360° video, and computer generated virtual reality. J Environ Psychol 72:101500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101500

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lucie Soumoy and Yasmine Shekri for their considerable contribution to the construction of the Darius Café 360IV as actor-director. We would also like to thank the Darius Café for agreeing to open the doors of their establishment. Finally, thank you to Cheyenne Poulet for her help in encoding the stimuli of the 360IV.

Funding

This work was funded by Université de Liège, BSH: Bourse des Sciences Humaines, Clara Della Libera.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Clara Della Libera and Jessica Simon declare to share the first authorship.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Della Libera, C., Simon, J., Larøi, F. et al. Using 360-degree immersive videos to assess multiple transdiagnostic symptoms: A study focusing on fear of negative evaluation, paranoid thoughts, negative automatic thoughts, and craving. Virtual Reality 27, 3565–3580 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-023-00779-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-023-00779-y