Abstract

This systematic review aims to identify the demographic, clinical and psychological factors associated with post-traumatic growth (PTG) in parents following their child’s admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). Papers published up to September 2021 were identified following a search of electronic databases (PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, PTSDpubs and EMBASE). Studies were included if they involved a sample of parents whose children were previously admitted to ICU and reported correlational data. 1777 papers were reviewed. Fourteen studies were eligible for inclusion; four were deemed to be of good methodological quality, two were poor, and the remaining eight studies were fair. Factors associated with PTG were identified. Mothers, and parents of older children, experienced greater PTG. Parents who perceived their child’s illness as more severe had greater PTG. Strong associations were uncovered between PTG and post-traumatic stress, psychological well-being and coping. PTG is commonly experienced by this population. Psychological factors are more commonly associated with PTG in comparison with demographic and clinical factors, suggesting that parents’ subjective ICU experience may be greater associated with PTG than the objective reality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The admission of a child to intensive care is a stressful event for families (Bronner et al., 2008; Colville & Gracey, 2006). Admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) is especially distressing for parents and there can be lasting psychological after-effects for them because of this experience (Hill et al., 2018). After-effects of an intensive care admission for parents include anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms (Als et al., 2015; Baker & Gledhill, 2017).

Parents experience high rates of trauma exposure whilst in the unit, both via the witnessing of the threat to the life of their child and via exposure to the distress experienced by other children and their families (Colville & Gracey, 2006; Nelson & Gold, 2012). Additionally, parents can find the intensive care environment to be frightening (Dahav & Sjostrom-Strand, 2018; Oxley, 2015). In a recent qualitative investigation, parents described intensive care as “being in another world”, with an emphasis on the unit being unpleasant, intense and stressful, and often felt overwhelmed by the technical equipment, noise, medical language and high level of activity in the unit (Dahav & Sjostrom-Strand, 2018, p. 365).

Recent reviews suggest that between 10 and 21% of parents experience persistent post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms following admission of their child to intensive care (Nelson & Gold, 2012), with up to 84% of parents still experiencing these symptoms 3 months following their child’s discharge (Bronner et al., 2008). Factors associated with PTSD symptoms in parents include retrospective reports of stress experienced during admission (Colville & Gracey, 2006), unexpected admission, parents’ degree of worry that their child might die, and the occurrence of another hospital admission/traumatic event after the index admission (Baluffi et al., 2004).

The hallmark symptoms of PTSD, including intrusive re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013), have been well documented amongst parents of NICU children (Aftyka et al., 2014; Lefkowitz et al., 2010) and parents of PICU children (Bronner et al., 2010; Rees et al., 2004). Less precedence has been given to the positive psychological change potentially experienced following a traumatic event, namely, post-traumatic growth (PTG). PTG is a term coined by Tedeschi and Calhoun in 1995, though its concept of origin is timeworn. This phenomenon refers to how an individual may experience positive personal change following life-altering adversity. This positive change can occur across five known domains; (1) having a greater appreciation of life, (2) improved interpersonal relationships, (3) greater perceived personal strength, (4) recognition of new possibilities in one’s life and (5) spiritual or religious growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996, 2004).

Previous studies have demonstrated that PTG is prevalent in parents of children diagnosed with cancer (Hullmann et al., 2014; Hungerbuehler et al., 2011), type 1 diabetes (Hungerbuehler et al., 2011), and children awaiting corrective surgery for congenital disease (Li et al., 2012), indicating the traumatic nature of such diagnoses. Hungerbuehler et al. (2011) found that parents reported significant levels of PTG 3 years after their child’s diagnosis of diabetes or cancer, but that mothers reported greater levels of PTG than fathers. Levels of PTG were best explained by the quality of family relationships, parents’ psychological distress and children’s medical characteristics (Hungerbuehler et al., 2011). This calls into investigation the acutely traumatic experiences of parents of children with serious paediatric illness and how these may affect levels of PTG in this population.

Significant levels of PTG have previously been reported amongst parents of children with serious paediatric illness (Picoraro et al., 2014); however, a dearth of literature exists examining the development of PTG in parents whose children have been admitted to intensive care specifically. The present systematic review was undertaken to synthesise and critically evaluate the available evidence surrounding factors associated with PTG in parents of children admitted to intensive care. It is important to identify the factors associated with PTG so that we are more aware of parents who are less likely, or more likely, to experience PTG following their NICU or PICU experience with their child (for example, when seeking to employ targeted clinical interventions fostering PTG). This is the first systematic review seeking to corroborate the demographic, clinical and psychological factors associated with parental PTG following such an event.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the guidelines published on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., 2009).

Search Strategy and Study Selection Criteria

A search for potentially eligible papers up to September 2021 was undertaken across seven databases; PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, PTSDpubs and EMBASE. A combination of controlled vocabulary from databases (e.g. MeSH) and free text words was chosen to reflect the review's focus on the factors associated with PTG in parents whose children have been admitted to NICU or PICU. The search terms used included variations of ‘post-traumatic growth’, ‘parent’, ‘paediatric critical illness’, ‘PICU’ and ‘NICU’. The final search terms used are outlined in Supplementary Table 1.

We included empirical studies that were published in the English language and implemented a quantitative or mixed-methods design, in which (1) PTG was an outcome measure, and (2) demographic (e.g.—age, gender, family type or education level), clinical (e.g.—duration of NICU/PICU stay, gestational age, reason for admission, or severity of illness), or psychosocial data (e.g.—post-traumatic stress, coping, social support, or anxiety) were also reported. We included studies with a population of PICU parents or NICU parents. Studies were excluded if they (1) implemented a qualitative design, (2) featured a different clinical population (e.g.—ICU staff) or (3) reported no PTG-specific data. Reference lists of all eligible research studies and any relevant published reviews were also screened for relevant papers.

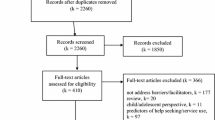

A PRISMA flow diagram depicting stages of the screening and selection process is presented in Fig. 1. The search strategy yielded 1913 papers for screening. Of 1777 papers retained after duplicates were removed, 1744 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thirty-three papers were identified as potentially eligible for inclusion. A further two papers were added following (1) manual screening of titles and abstracts of the bibliographies of those potentially included and (2) manual screening of the bibliographies of review papers yielded within the database search. This resulted in screening 35 full-text papers, 21 of which were excluded (see Fig. 1). A total of 14 papers were deemed eligible for inclusion in the review.

Several stages were employed in the screening of papers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify the studies eligible for inclusion in the review. Primarily, the electronic search across the seven databases was completed. Following this, any duplicate papers were identified and removed. The remaining papers underwent a two-stage screening process. In the first stage of screening, the titles and abstracts of all papers were screened by the first author (SOT). In the second stage, the full texts of potentially eligible papers were retrieved and reviewed independently by two review authors (SOT and CS) for eligibility, resulting in 92% interrater agreement (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.83). Two further reviewers (PA and DMcC) resolved any discrepancies through discussion. Reasons for excluding studies at all stages were noted.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Results were tabulated to capture the key data extracted from the included studies. The following methodological information was extracted for each study: author, year and country of origin; study aim/objective; study design; data collection method; sample; study setting (NICU or PICU); PTG measure employed; and other variables examined (including demographic, clinical and psychological variables) (see Table 1).

The following key findings were extracted for each study: levels of PTG, demographic factors associated with PTG, clinical factors associated with PTG and psychological factors associated with PTG (see Table 2). All data were extracted independently by two reviewers (SOT and CS) and cross-checked by two other reviewers (PA and DMcC) for accuracy with any discrepancies resolved through discussion. Because of methodological heterogeneity uncovered within the included studies, and variability in the method of reporting psychometric outcomes, a narrative analysis was conducted across all findings.

Quality Assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed independently by two review authors (SOT and CS), with two other reviewers (PA and DMcC) resolving any disagreements by discussion and consensus. As all the studies included in the present review employed quantitative methods, the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational and Cross-Sectional Studies, developed by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [NHLBI], was used to assess study quality and risk of bias (NHLBI & accessed, 2019). This tool aims to address common issues arising in cross-sectional and observational studies. The tool contains 14 questions, for which each rater can assign the answers “yes”, “no”, “CD” (cannot determine), “NA” (not applicable) or “NR” (not reported). The tool enabled the assignment of a rating of ‘poor’, ‘fair’ or ‘good’ to each study.

Findings

Description of the Included Studies

Characteristics of the included studies are outlined in Table 1. The 14 papers included in this review were published between 1999 and 2020, with twelve of the studies published within the last 10 years. The studies involved a total of 1311 participants and all employed either a cross-sectional or prospective quantitative study design. The studies were conducted in Australia, the United States, Spain, Israel, the United Kingdom, Poland and Turkey.

Considering the samples employed in the studies, the number of mothers (n = 922) far outweighed fathers (n = 389). This is because four of the included studies examined a mother-only sample (Boztepe, et al., 2015; Miles et al., 1999; Rozen et al., 2018; Taubman-Ben-Ari et al., 2010). Six studies looked at mother and father data combined (Aftyka et al., 2017; Brelsford et al., 2020; Colville & Cream, 2009; Parker, 2016; Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017, 2018), and four studies examined data from mothers and fathers separately (Aftyka et al., 2020; Barr, 2011, 2015, 2016). Overall, participant numbers in studies ranged from 25 to 210. A greater number of studies investigated PTG in a population of NICU parents (Aftyka et al., 2017, 2020; Barr, 2011, 2015, 2016; Boztepe, et al., 2015; Brelsford et al., 2020; Miles et al., 1999; Parker, 2016; Rozen et al., 2018; Taubman-Ben-Ari et al., 2010), compared to a population of PICU parents (Colville & Cream, 2009; Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017, 2018).

Twelve of the included studies identified the PTG in parents whose child had been admitted to intensive care as a primary focus. The aims and objectives of the studies varied greatly, with much heterogeneity amongst the variables of interest. For example, nine studies broadly investigated how different psychological and clinical factors are associated with PTG and parental adjustment following intensive care, two studies evaluated the incidence and severity of PTG amongst parents following intensive care, one study examined the risk factors associated with PTSD and PTG in these parents and finally, two studies explored psychological well-being of this population in general. The psychometric tools used to measure PTG in the studies included the following: The Post-traumatic Growth Inventory [PTGI] (Aftyka et al., 2017, 2020; Barr, 2011; Boztepe, et al., 2015; Brelsford et al., 2020; Colville & Cream, 2009; Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017, 2018; Rozen et al., 2018; Taubman-Ben-Ari et al., 2010), the Positive Changes subscale of the Changes in Outlook Questionnaire [CiO-POS] (Barr, 2015, 2016), the Personal Growth subscale of the Psychological Well-being Scales [PGS] (Parker, 2016) and a Developmental Impact Rating Scale developed by the authors for the purpose of measuring growth (Miles et al., 1999).

Methodological Quality of the Included Studies

Two reviewers (SOT and CS) independently rated the quality of each study resulting in 92% interrater agreement (Cohen’s Kappa of 0.87). Use of the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational and Cross-Sectional Studies deemed eight studies to be of “fair” quality and four studies to be of “good” quality. Two studies were assigned the rating “poor” (See Table 3).

Common issues arising amongst studies included the absence of pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria for recruitment (n = 8) and a lack of reporting sample size justification and power calculations (n = 11). Additionally, no studies incorporated a sufficient timeframe for observing the development of PTG within a population of parents whose child was admitted, or had previously been admitted, to intensive care (n = 14). The longest timeframe employed within the included studies was a follow-up of 16 months following the child’s birth (with baseline measurement occurring at time of birth) (Miles et al., 1999). The median timeframe employed in the studies was 7.5 months.

Levels of PTG Amongst Parents Following Admission of their Child to the Intensive Care Unit

Parent samples in all the included studies endorsed a medium to very high level of PTG in the weeks, months and years following their child’s admission to intensive care. Due to variability in both the psychometric tools used, and the method of reporting, providing an estimate of the average prevalence of PTG within all study samples presented a challenge. Studies employing the PTGI measure that reported a mean total PTG demonstrated scores that ranged from 47.4 to 75.70, indicating a moderate to very high degree of PTG (Aftyka et al., 2017, 2020; Barr, 2011; Boztepe et al., 2015; Brelsford et al., 2020; Colville & Cream, 2009; Rodríguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017, 2018; Rozen et al., 2018; Taubman-Ben-Ari et al., 2010).

What are the Demographic Factors Associated with PTG in Parents Following Admission of Their Child to the Intensive Care Unit?

Four studies demonstrated significant associations between PTG and demographic factors, including parent gender (Barr, 2015; Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2018), child age (Colville & Cream, 2009), parent education level (Rozen et al., 2018) and socioeconomic status (Rozen et al., 2018). Mothers of children previously admitted to intensive care were significantly more likely to experience higher PTG than fathers [p < .01; p ≤ .05] (Barr, 2015; Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2018). Furthermore, parents of older children exhibited significantly higher levels of PTG following their child’s PICU admission, when compared to parents of younger children [p < .05] (Colville & Cream, 2009). Finally, in their 2018 study, Rozen et al. highlighted associations between PTG and parent education level; with parents with lower education levels endorsing greater personal growth [p ≤ .01] and spirituality [p ≤ .05] (Rozen et al., 2018). Parents of lower socioeconomic status also reported greater growth in interpersonal relationships [p ≤ .05] (Rozen et al., 2018).

What are the Clinical Factors Associated with PTG in Parents Following Admission of Their Child to the Intensive Care Unit?

Six studies demonstrated significant associations between PTG and clinical factors including parental perceptions of child’s illness severity (Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017, 2018), child’s illness severity (Rozen et al., 2018), child ventilation (Colville & Cream, 2009), child level of technology dependence (Miles et al., 1999), child’s mental development (Miles et al., 1999) and child survival (Aftyka et al., 2017). Parents who perceived their child’s illness to be more severe [p ≤ .05], and parents whose children were objectively more severely-ill [p ≤ .01], were demonstrated as significantly more likely to experience PTG (Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017, 2018; Rozen et al., 2018). Colville and Cream (2009) found that parents of ventilated children exhibited higher PTG scores than parents of non-ventilated children [(p < .05]. However, in another study, mothers of children who were more technology-dependent (i.e.—had a greater number of technologies involved in their care) at an early age were significantly less likely to experience PTG when compared to mothers whose children were less dependent [p < .05] (Miles et al., 1999). Mothers of children with lower mental development were also significantly less likely to experience PTG [p < .01] (Miles et al., 1999). Finally, Aftyka et al. (2017) found that parents of children who survived following their admission to intensive care experienced greater levels of PTG than bereaved parents [p < .001].

What are the Psychological Factors Associated with PTG in Parents Following Admission of Their Child to the Intensive Care Unit?

All studies included in this review demonstrated significant associations between PTG and psychological factors. In total, thirty-nine psychometric tools were used to examine a wide array of psychological variables. A full breakdown of the psychometric tools used to examine each variable is outlined in Supplementary Table 2.

Demonstrated Associations Between PTG and Post-Traumatic Stress

The psychological presentation with the greatest links to PTG amongst parents was post-traumatic stress. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress, including intrusions, avoidance and hyperarousal, were found to be significantly positively associated with PTG in all the studies in which they were examined (Aftyka et al., 2017; Boztepe et al., 2015; Colville & Cream, 2009; Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017), with particularly strong links to interpersonal and transpersonal growth uncovered (Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017). Consistent with the available literature, Colville and Cream (2009) found the relationship between PTG and PTSD symptoms to be curvilinear; suggesting that parents experiencing a moderate level of PTSD are more likely to exhibit PTG when compared to those experiencing lower or higher levels of post-traumatic stress. However, this curvilinear relationship was contraindicated in Rodriguez-Rey and Alonso-Tapia’s (2017), the results of which show that high levels of psychopathology are also linked to PTG. Given that PTG is more strongly linked to positive outcomes over 2 years following the traumatic event (Helgeson et al., 2006), and these studies measure PTG at 4 months and 6 months post-admission, respectively, the nature of the relationship between PTG and PTSD warrants further longitudinal investigation.

Demonstrated Associations Between PTG and Parental Stress

Environmental stressors in both the NICU environment (e.g. the sights and sounds of the unit and infants’ appearance) (Barr, 2011), and the PICU environment (e.g. medical procedures conducted on the child and separation from the child) (Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2018), were found to be predictors of PTG in parents of admitted children, particularly mothers (Barr, 2011). Rodriguez-Rey and Alonso-Tapia (2018) also found that positive emotions experienced during admission were positively related to PTG 6 months following discharge [r = .20, p ≤ .05]. Conversely, parents who experienced greater worry in relation to their child’s health were less likely to experience PTG during the first 16 months following their child’s admission [p < .001] (Miles et al., 1999).

Parker (2016) also demonstrated that personal growth at time of admission to intensive care was significantly negatively correlated with the symptoms of acute stress disorder at 3-week follow-up [r = − .50, p < .01]. Whilst not explored in other studies, this finding indicates that personal growth (being open to new experiences and considering the self as growing and expanding over time) may actually be a protective factor against the development of acute stress disorder amongst these parents.

Demonstrated associations Between PTG and Parent Psychological Well-Being

Greater psychosocial well-being and more positive mental health in mothers were significantly (moderately) associated with positive changes in outlook in mothers [r = .44, p < .01], but not in fathers (Barr, 2016). Parker (2016) replicated this finding across four domains of psychological well-being [all p < .05], identifying a particularly strong association between positive relations with others and personal growth [r = .47, p < .01].

Considering psychological presentations and how these are linked to PTG, Rodriguez-Rey and Alonso-Tapia (2017) found PTG to be significantly and positively correlated with both anxiety [r = .22, p ≤ .01] and depression [r = .20, p ≤ .05]. Interestingly, transpersonal growth (encompassing spiritual beliefs and life possibilities) was most strongly associated with greater anxiety [r = .29, p ≤ .001] and depression [r = .31, p ≤ .001] in parents of children whose children had been admitted to intensive care (Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017). These findings add weight to the evidence that positive and negative effects of traumatic events (such as a child’s intensive care hospitalisation) can coexist and manifest within the same person.

Demonstrated Associations Between PTG and Coping Strategies

Several significant positive relationships were uncovered between PTG and the use of adaptive coping strategies. The most strongly associated coping strategies were those of positive reinterpretation (Aftyka et al., 2017), planful problem-solving and positive reappraisal (Barr, 2011) [all p < .001], with moderate associations revealed between PTG and task-oriented coping, and PTG and avoidance-oriented coping [both p < .01] (Aftyka et al., 2017).

Coping strategies were more commonly linked to greater PTG in mothers rather than fathers (Aftyka et al., 2020; Barr, 2011). Gender differences were found in the type of coping strategies adopted by mothers (accepting responsibility [r = .43, p < .001], planful problem-solving [r = .30, p < .01], escape avoidance [r = .36, p < .01], social support seeking [r = .33, p < .01], confrontive coping [r = .32, p < .01], active coping [r = .50, p < .01], planning [r = .44, p < .01], suppression of competing activities [r = .41, p < .01] and focus on and venting of emotions [r = v39, p < .05]) versus fathers (confrontive coping [r = .26, p < .05]), with self-controlling linked to greater PTG in both mothers [r = .38, p < .001] and fathers [r = .24, p < .05] (Aftyka et al., 2020; Barr, 2011).

Demonstrated Associations Between PTG and Social Support

One study identified a positive relationship between PTG and social support, indicating that parents who perceived more social support from their friends, family and significant other were more likely to experience PTG [all p < .05] (Boztepe et al., 2015).

Demonstrated Associations Between PTG and Attitudes Towards Death

Barr (2011, 2015) sought to investigate parents’ attitudes towards death (including how much they both feared and accepted death) and how these may be related to PTG following their child’s admission to intensive care. Gender differences in attitudes towards death were revealed; escape acceptance (i.e.—accepting death as the ultimate solution to life’s problems and worries) was significantly negatively correlated with PTG in mothers [r = − .26, p < .05] (Barr, 2015), whereas fearing death was significantly positively associated with PTG in fathers [r = .37, p < .01] (Barr, 2011). Death avoidance (or avoiding thoughts of death) was significantly positively correlated with positive changes in outlook in both mothers [(r = .31, p < .05] and fathers [r = .44, p = < .001].

With these findings, Barr (2011, 2015) suggests that parents who actively feared and avoided the idea of death were more likely to experience PTG in the aftermath of their child’s admission to intensive care. These findings reinforce previous literature that has found existential emotions to be adaptive as well as maladaptive (Cozzolino, 2006; Park et al., 2005; Tangney & Fischer, 1995).

Other Demonstrated Associations with PTG

Four final relationships were uncovered in this review, between PTG and (1) maternal identity, (2) marital adaptation, (3) guilt-proneness and (4) religiosity. Mothers of children with a higher sense of maternal identity in the early months of life were significantly less likely to experience positive growth [p < .05] (Miles et al., 1999). However, higher personal growth 1 year following the child’s admission was associated with better marital adaptation immediately following admission [r = .30, p < .05] (Taubman-Ben-Ari et al., 2010). Barr (2011) found that guilt-proneness in fathers is significantly positively associated with PTG [r = .25, p < .05]. In this case, Barr (2011) assumes this to be adaptive guilt, which has been previously associated with empathy, altruism and perspective taking (Tangney & Fischer, 1995). Finally, Brelsford et al (2020) have demonstrated associations between PTG and positive religious coping [r = .41, p < .05], spiritual disclosure [r = .43, p < .05], theistic sanctification (the perception of God’s presence in the parent–child relationships) [r = .52, p < .05] and non-theistic sanctification (the perception of the sacred in the parent–child relationship) [r = .73, p < .001].

Discussion

The experience of one’s child being admitted to intensive care represents a significant traumatic event in the life of a parent. Whilst the high rate of resulting post-traumatic stress symptoms has been previously documented amongst this population of parents (Bronner et al., 2010; Lefkowitz et al., 2010; Rees et al., 2004), the positive change parents undergo following their child’s discharge from the intensive care unit has been a less investigated topic. The present review reveals that the phenomenon of PTG is highly prevalent amongst these parents and has strong links to parental psychological well-being and patterns of adaptive coping.

The finding that PTG is more common amongst mothers when compared to fathers is unsurprising. Previous research demonstrates that the female gender is a significant predictor of PTG in parents of critically ill children (Hungerbuehler et al., 2011). However, whether the reason for this lies within the maternal parenting role, or the willingness to be in contact with distressing thoughts, feelings and images, which Kashdan and Kane (2011) posit serves as a catalyst for the development of PTG, warrants further examination. It must also be noted that most studies in the present review examined maternal PTG. It remains important that future research in the area of PTG seeks to include a greater number of fathers.

Perhaps more interesting is the conflicting evidence regarding the possible curvilinear relationship between PTSD and PTG uncovered within the findings of this review (Colville & Cream, 2009; Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017). One possible explanation for the divergent findings of this review lies in the significant relationship identified between PTG and parents’ perceptions of the severity of their child’s illness (Rodriguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2017, 2018). Given that the time spent in intensive care can be an acutely distressing experience that may impact on parents’ perceptions of illness severity, future research should endeavour to track both perceptions of illness severity, and PTG, over time, to assess whether this variable may moderate the relationship between PTSD and PTG. This review further highlights the need for longitudinal research with parents following their child’s discharge from intensive care to examine the trajectory of the PTG experienced.

Davydow et al.’s (2010) review of the factors associated with PTSD symptoms in parents of children admitted to intensive care highlighted that psychological variables were more strongly associated with subsequent PTS symptoms than demographic or medical variables. These psychological variables included retrospective reports of stress experienced during admission (Baluffi et al., 2004; Colville & Gracey, 2006) and parents’ perceptions of how life-threatening their child’s illness is (at the time of admission) (Baluffi et al., 2004). These findings suggest that, in terms of predicting psychological outcome, subjective experience is more important than objective aspects of the ICU experience—i.e. how something is experienced is more of a predictor of future distress than what is experienced (Colville & Pierce, 2012). Indeed, it is widely acknowledged that acute stress can result in significant distortion effects on both one’s current perception of an event and recollections in memory (Hancock & Weaver, 2005; Mather & Sutherland, 2011). Findings uncovered in the present review suggest that this same underlying process may be at play in the development of PTG, as in the development of PTSD, over time.

The strategies employed to cope with the post intensive care experience were another significant factor associated with the development of PTG. The adaptive nature of existential emotions, previously often thought to be maladaptive, has been demonstrated (Barr, 2015). In the same way that Cozzolino (2006) postulates that contemplating one’s own mortality can promote personal growth; the existential emotion of fearing death was significantly associated with PTG (Barr, 2011).

Prior to Barr’s (2015) novel finding, death avoidance was widely believed to hamper facets of personal growth (Cozzolino, 2006; Tomer et al., 2007). However, this finding suggests that parents of children previously admitted to intensive care may use avoidance of thoughts of death as an effective coping strategy. One theory why this strategy may promote PTG suggests that this is due to the experience of their child’s ICU admission being uniquely mortality salient (i.e.—resulting in an awareness that death is inevitable) (Lykins et al., 2007). The traumatic experience of their child’s admission to intensive care may cause parents to appraise the fragility of life, thus resulting in positive appraisal and PTG. Future research should seek to confirm this finding and more closely examine the processes involved.

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

To the author’s knowledge, this is the first systematic review to synthesis evidence relating to the factors associated with PTG in a population of parents whose children have previously been admitted to intensive care. The review employed a comprehensive screening and quality appraisal process which may be viewed as a strength.

Despite this, the present review was not without limitations. Due to the heterogeneity of the variables examined within the studies, a narrative synthesis was undertaken with no meta-analytic component. Thus, the review provides a mainly descriptive account of the findings. Many studies included in this review were deemed to be of “fair” quality (n = 6), with some concerns regarding risk of bias. The findings of the study should be considered in the context of their assessed methodological rigour. Finally, this review only included studies employing a quantitative design. Research using qualitative methods may have contributed to our understanding of PTG in this population.

Clinical Implications

The positive links established between PTG and the psychological well-being of parents following their child’s admission to intensive care are of clinical relevance. Future research should seek to rigorously evaluate clinical interventions that seek to promote PTG amongst these parents, as evidence from this review suggests that this may in turn increase psychological well-being.

Considering the well-documented link between parent psychopathology and child psychopathology, and the observation that almost half of all children admitted to intensive care are aged below 1 year (Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network, 2005), it may be most appropriate to provide such an intervention at parent level. Interventions to promote PTG in parents therefore denote a valuable investigation when seeking to improve family-wide psychological well-being. Such interventions should be developed and evaluated in order to facilitate growth and positive outcomes for parents of children previously admitted to intensive care.

Future Research

The findings of the present review highlight the heterogeneity amongst the factors examined when seeking to investigate PTG in this population of parents. Future research should seek to employ greater homogeneity when examining what predicts PTG amongst parents whose child has been admitted to intensive care. More focused research would help in the design of a feasible parent intervention to promote PTG. Additionally, fathers were underrepresented in the present review, when compared to mothers. Fathers are historically underrepresented in psychology and healthcare research (Seiffge-Krenke, 2002; Garfield & Isacco, 2012), despite their important role in child development (Sarkadi et al., 2008). Future research in the area of PTG should seek to include more paternal voices.

Finally, this area of research would benefit greatly from more studies employing a longitudinal design. Helgeson et al. (2006) have highlighted that PTG-related outcomes often take over 2 years to manifest. None of the included studies in this review have incorporated a timeframe for observing PTG greater than 16 months, with the median timeframe being 9.5 months following ICU admission. Future research should aim to fill this gap in the literature in a bid to investigate the long-term trajectory of PTG in this population of parents.

Conclusion

The present systematic review demonstrates that PTG is a common positive outcome for parents following the exceptionally distressing event of having a child admitted to the intensive care unit. Whilst mothers more commonly experienced PTG, psychological factors were more commonly associated with PTG in comparison with demographic and clinical factors. Such psychological factors include post-traumatic stress, coping and perceived severity of their child’s illness. This suggests that parents’ subjective experience of intensive care may be greater associated with PTG than the objective reality. This is an important consideration when seeking to develop psychological interventions for parents of children admitted to intensive care, suggesting that, for example, it may be beneficial to screen parents’ levels of subjective distress whilst in ICU with their child. Future research would benefit from examining variables of greater homogeneity, and employing longer timeframes, when investigating PTG amongst parents of children previously admitted to intensive care.

References

Aftyka, A., Rozalska-Walaszek, I., Rosa, W., Rybojad, B., & Karakuła-Juchnowicz, H. (2017). Post-traumatic growth in parents after infants’ neonatal intensive care unit hospitalisation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(5–6), 727–734.

Aftyka, A., Rybojad, B., Rozalska-Walaszek, I., Rzoñca, P., & Humeniuk, E. (2014). Post-traumatic stress disorder in parents of children hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU): medical and demographic risk factors. Psychiatria Danubina, 26(4), 352.

Aftyka, A., Rozalska, I., & Milanowska, J. (2020). Is post-traumatic growth possible in the parents of former patients of neonatal intensive care units? Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 27(1), 106–112.

Als, L. C., Nadel, S., Cooper, M., Vickers, B., & Garralda, M. E. (2015). A supported psychoeducational intervention to improve family mental health following discharge from paediatric intensive care: Feasibility and pilot randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal Open, 5(12), e009581.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Pub.

Baker, S. C., & Gledhill, J. A. (2017). Systematic review of interventions to reduce psychiatric morbidity in parents and children after PICU admissions. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 18(4), 343–348.

Balluffi, A., Kassam-Adams, N., Kazak, A., Tucker, M., Dominguez, T., & Helfaer, M. (2004). Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 5(6), 547–553.

Barr, P. (2011). Posttraumatic growth in parents of infants hospitalized in a neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 16(2), 117–134.

Barr, P. (2015). Death attitudes and changes in existential outlook in parents of vulnerable newborns. Death Studies, 39(8), 508–514.

Barr, P. (2016). Psychological well-being, positive changes in outlook and mental health in parents of sick newborns. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 34(3), 260–270.

Bates, J. E., Freeland, C. A., & Lounsbury, M. L. (1979). Measurement of infant difficulties. Child Development, 50, 794–803.

Boztepe, H., Inci, F., & Tanhan, F. (2015). Posttraumatic growth in mothers after infant admission to neonatal intensive care unit. Paediatria Croatica, 59(1), 14–18.

Brelsford, G. M., Doheny, K. K., & Nestler, L. (2020). Parents’ post-traumatic growth and spirituality post-neonatal intensive care unit discharge. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 48(1), 34–43.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measure of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment Theory and Close Relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford.

Bronner, M. B., Knoester, H., Bos, A. P., Last, B. F., & Grootenhuis, M. A. (2008). Follow-up after paediatric intensive care treatment: Parental posttraumatic stress. Acta Paediatrica, 97(2), 181–186.

Bronner, M. B., Peek, N., Knoester, H., Bos, A. P., Last, B. F., & Grootenhuis, M. A. (2010). Course and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in parents after pediatric intensive care treatment of their child. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(9), 966–974.

Cardeña, E., Koopman, C., Classen, C., Waelde, L. C., & Spiegel, D. (2000). Psychometric properties of the Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire (SASRQ): A valid and reliable measure of acute stress. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(4), 719–734.

Carter, M. C., & Miles, M. S. (1989). The parental stressor scale: Pediatric intensive care unit. Maternal-Child Nursing Journal, 18(3), 187–198.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267.

Caldwell, B., & Bradley, R. (1984). Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Colville, G., & Cream, P. (2009). Post-traumatic growth in parents after a child’s admission to intensive care: maybe Nietzsche was right? Intensive Care Medicine, 35(5), 919.

Colville, G. A., & Gracey, D. (2006). Mothers’ recollections of the paediatric intensive care unit: Associations with psychopathology and views on follow up. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 22(1), 49–55.

Colville, G., & Pierce, C. (2012). Patterns of post-traumatic stress symptoms in families after paediatric intensive care. Intensive Care Medicine, 38(9), 1523–1531.

Cozzolino, P. J. (2006). Death contemplation, growth, and defence: Converging evidence of dual-existential systems? Psychological Inquiry, 17, 278–287.

Dahav, P., & Sjöström-Strand, A. (2018). Parents’ experiences of their child being admitted to a paediatric intensive care unit: A qualitative study–like being in another world. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(1), 363–370.

Davidson, J. R., Book, S. W., Colket, J. T., Tupler, L. A., Roth, S., David, D., & Davison, R. M. (1997). Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 153–160.

Davydow, D. S., Richardson, L. P., Zatzick, D. F., & Katon, W. J. (2010). Psychiatric morbidity in pediatric critical illness survivors: A comprehensive review of the literature. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164(4), 377–385.

Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Deal, A. G. (1988). Enabling and empowering families: Principles and guidelines for practice. Brooklyn.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 992–1003.

Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the united states on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365–376.

Fowers, B. J., & Olson, P. H. (1989). “ENRICH” marital inventory: A discriminant validation assessment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 15, 65–79.

Garfield, C. F., & Isacco III, A. J. (2012). Urban fathers’ involvement in their child’s health and healthcare. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 13(1), 32.

Hancock, P. A., & Weaver, J. L. (2005). On time distortion under stress. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 6(2), 193–211.

Helgeson, V. S., Reynolds, K. A., & Tomich, P. L. (2006). A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 797.

Hill, C., Knafl, K. A., & Santacroce, S. J. (2018). Family-centered care from the perspective of parents of children cared for in a pediatric intensive care unit: An integrative review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 41, 22–33.

Horowitz, M., Wilner, N., & Alvarez, W. (1979). Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41(3), 209–218.

Hullmann, S., Fedele, D., Molzon, E., Mayes, S., & Mullins, L. (2014). Posttraumatic growth and hope in parents of children with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 32(6), 696–707.

Hungerbuehler, I., Vollrath, M. E., & Landolt, M. A. (2011). Posttraumatic growth in mothers and fathers of children with severe illnesses. Journal of Health Psychology, 16(8), 1259–1267.

Joseph, S., Williams, R., & Yule, W. (1993). Changes in outlook following disaster: The preliminary development of a measure to assess positive and negative responses. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(2), 271–279.

Kashdan, T. B., & Kane, J. Q. (2011). Post-traumatic distress and the presence of post-traumatic growth and meaning in life: Experiential avoidance as a moderator. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(1), 84–89.

Lefkowitz, D. S., Baxt, C., & Evans, J. R. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 17(3), 230–237.

Lester, D. (1990). The Collett-Lester Fear of Death Scale: The original version and a revision. Death Studies, 14, 451–468.

Levy-Shiff, R., Sharir, H., & Mogilner, M. B. (1989). Mother- and father-preterm infant relationship in the hospital preterm nursery. Child Development, 60, 93–102.

Li, Y., Cao, F., Cao, D., Wang, Q., & Cui, N. (2012). Predictors of posttraumatic growth among parents of children undergoing inpatient corrective surgery for congenital disease. Journal of Paediatric Surgery, 47(11), 2011–2021.

Lykins, E. L., Segerstrom, S. C., Averill, A. J., Evans, D. R., & Kemeny, M. E. (2007). Goal shifts following reminders of mortality: Reconciling posttraumatic growth and terror management theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(8), 1088–1099.

Mather, M., & Sutherland, M. R. (2011). Arousal-biased competition in perception and memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(2), 114–133.

McCubbin, H. I., & Thompson, A. I. (Eds.). (1987). Family assessment inventories for research and practice. University of Wisconsin Press.

Miles, M. S. (1998). Parental role attainment with medically fragile infants. Grant Report to the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Health.

Miles, M. S., Funk, S. G., & Carlson, J. (1993). Parental stressor scale: neonatal intensive care unit. Nursing Research, 42, 148–152.

Miles, M. S., Holditch-Davis, D., Burchinal, P., & Nelson, D. (1999). Distress and growth outcomes in mothers of medically fragile infants. Nursing Research, 48(3), 129–140.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group*. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools. Retrieved November 2019, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

Nelson, L. P., & Gold, J. I. (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder in children and their parents following admission to the pediatric intensive care unit: A review. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 13(3), 338–347.

Oxley, R. (2015). Parents’ experiences of their child’s admission to paediatric intensive care. Nursing Children and Young People, 27(4).

Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network (PICA). (2005). Annual Report 2003–2004. Universities of Leeds.

Park, C. L., Mills-Baxter, M. A., & Fenster, J. R. (2005). Post-traumatic growth from life’s most traumatic event: Influences on elders’ current coping and adjustment. Traumatology, 11, 297–306.

Parker, K. H. (2016). NICU Parental Mental Health and Infant Outcomes: Effects of Psychological Well-Being and Psychopathology. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Loma Linda University, California, USA.

Pearlin, L. I., Lieberman, M. A., Menaghan, E. G., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356.

Picoraro, J. A., Womer, J. W., Kazak, A. E., & Feudtner, C. (2014). Posttraumatic growth in parents and pediatric patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(2), 209–218.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Rees, G., Gledhill, J., Garralda, M. E., & Nadel, S. (2004). Psychiatric outcome following paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission: A cohort study. Intensive Care Medicine, 30(8), 1607–1614.

Rodríguez-Rey, R., & Alonso-Tapia, J. (2017). Relation between parental psychopathology and posttraumatic growth after a child’s admission to intensive care: Two faces of the same coin? Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 43, 156–161.

Rodríguez-Rey, R., & Alonso-Tapia, J. (2018). Predicting posttraumatic growth in mothers and fathers of critically ill children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 1–10.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceive the Self. Basic Books.

Rozen, G., Taubman–Ben-Ari, O., Strauss, T., & Morag, I. (2018). Personal growth of mothers of preterms: Objective severity of the event, subjective stress, personal resources, and maternal emotional support. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(7), 2167–2186.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2006). Best news yet on the six-factor model of well-being. Social Science Research, 35(4), 1103–1119.

Sarkadi, A., Kristiansson, R., Oberklaid, F., & Bremberg, S. (2008). Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatrica, 97(2), 153–158.

Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2002). “Come on, say something, Dad!”: Communication and coping in fathers of diabetic adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(5), 439–450.

Smilkstein, G., Ashworth, C., & Montano, D. (1982). Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. Journal of Family Practice, 15, 303–311.

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E. M., Christopher, P. J., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200.

Tangney, J. P., & Fischer, K. W. (Eds.). (1995). Self-conscious emotions: The psychology of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride. Guilford Press.

Taubman–Ben-Ari, O., Findler, L., & Kuint, J. (2010). Personal growth in the wake of stress: the case of mothers of preterm twins. The Journal of Psychology, 144(2), 185–204.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The Posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18.

Tomer, A., Eliason, G. T., & Wong, P. T. (Eds.). (2007). Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes. Psychology Press.

Veit, C. T., & Ware, J. E. (1983). The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(5), 730.

Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (1997). The Impact of Event Scale - Revised. In J. P. Wilson & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD: A Practitioner’s Handbook (pp. 399–411). Guilford Press.

Wong, P. T. P., Reker, G. T., & Gesser, G. (1994). Death Attitude Profile - Revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes toward death. In R. A. Neimeyer (Ed.), Death anxiety handbook: Research, instrumentation, and application (pp. 121–148). Taylor & Francis.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370.

Acknowledgements

This systematic review was conducted by the first author in partial fulfilment of the Doctorate in Clinical Psychology in Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S. O.’ Toole, C. Suarez, P. Adair, A. McAleese, S. Willis, D. McCormack have no known conflict of interest associated with this systematic review.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Toole, S., Suarez, C., Adair, P. et al. A Systematic Review of the Factors Associated with Post-Traumatic Growth in Parents Following Admission of Their Child to the Intensive Care Unit. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 29, 509–537 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-022-09880-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-022-09880-x