Abstract

Introduction

Compared to straight people, older sexual minorities are at a higher risk of experiencing depression because they encounter additional stressors related to sexual minority status. Nonetheless, the stressor appraisal process and the coping mechanism employed by sexual minority older adults remain understudied. Additionally, research on forgiveness in sexual minorities is scant, especially among older populations. This study examines the extent to which negative social interactions and shame about sexual minority identity explain perceived stress that underlines depression and the relative importance of forgiveness, social support, and resilience in forming adaptive coping, which moderates between stress and depression among sexual minority older adults.

Methods

We used hierarchical component models in structural equation modeling to analyze data—collected in 2017—from a sample of 50 lesbian women and 50 gay men older than 50 years.

Results

Negative social interactions and shame due to heterosexism significantly predict perceived stress, which in turn significantly predicts depressive symptoms. Also, forgiveness is more powerful at forming adaptive coping than social support, while resilience is the most powerful. Moreover, adaptive coping significantly moderates between stress and depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

Forgiveness and resilience are more important than social support in buffering between stress and mental health problems among older lesbian women and gay men.

Policy Implications

Access to forgiveness interventions should be readily available within mental health settings to promote the mental wellbeing and adaptive coping of clients who experienced interpersonal transgressions or negative self-thoughts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the United States (U.S.), aging populations have grown rapidly at an unprecedented rate (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). There are now more people over 50 years old than those under 25 years (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Concurrently, older sexual minority populations are growing and experiencing various age-related challenges; these populations include older lesbian women (i.e., lesbians), gay men, bisexual persons, and other non-heterosexual persons (Meyer et al., 2020). Research indicates that mental health problems among sexual minority older adults are disproportionately prevalent compared to straight/heterosexual people, and the mental health disparities grow even larger in later life (Dai & Meyer, 2019). For instance, the odds of having a depressive disorder are 110% higher for gay men aged 50 to 64 years than for straight men the same age; for men over 65, the odds are 170% higher for gay men than for straight men (Dai & Meyer, 2019). Nonetheless, research investigating contributing and preventive factors for depression among older sexual minorities is limited. More research attention in this area is crucially needed to guide the development and implementation of effective interventions and health policies for these populations.

To address the literature gap, the present study examines the extent that different stressors (i.e., sources of stress) contribute to subsequent perceived stress and the degree to which the perceived stress underlines depression with a sample of older lesbian women and gay men. This study also investigates the relative importance of forgiveness, social support, and resilience in forming adaptive coping that buffers between stress and depression among older sexual minorities, using structural equation modeling.

Stressors, Perceived Stress, and Depression

The minority stress theory is a widely accepted framework to study minority people’s mental health and the interaction between stressors and coping (Meyer, 2003). In addition to general stressors, minority people experience two additional types of minority-related stressors, which ultimately impact mental health: distal stressors and proximal stressors (Meyer, 2003). Distal stressors are objective external events or conditions that are potentially stressful and not contingent on subjective perceptions or appraisals of a person (e.g., negative social interaction). Conversely, proximal stressors are stressors from potentially stressful internal psychological processes that depend on personal perceptions and appraisals, which are more subjective and linked to self-identity (e.g., shame due to heterosexism; Meyer, 2003). Among older sexual minorities, these stressors—such as interpersonal discrimination as well as institutional and internalized homophobia—may impact their mental health and their needs for aging in place (Prasad et al., 2022). Consistent with this view, minority stressors are associated with diminished positive affect and heightened depressive symptoms among older gay men (Wight et al., 2012).

Negative social interaction is a crucial distal stressor (Velez et al., 2015) and is more frequently experienced by sexual minority older adults (Yarns et al., 2016). Also, the rate of negative social interaction increases as older sexual minorities age (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011). The Federal Bureau of Investigation (2020) estimated that 17% of hate crimes reported in 2019 in the U.S. was motivated by sexual-orientation bias. Additionally, among older sexual minorities, lifetime experiences of sexual orientation victimization and discrimination are associated with mental health problems, including depression (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013). Therefore, negative social interaction is a stressor that many older sexual minorities experience, which may have adverse downstream health consequences.

The internalization of negative societal attitudes such as heterosexism is another major stressor for sexual minority persons (Meyer, 2003). The feeling of shame due to heterosexism encompasses a range of negative emotions from embarrassment to strong humiliation about one’s own sexual minority identity and the sexual minority community because of societal heterosexism (Dickey-Chasins, 2000). Notably, such shame about sexual minority identity is still common among older sexual minorities (Prasad et al., 2022) and is linked to mental health problems (Szymanski & Mikorski, 2016). Additionally, shame due to heterosexism impedes older sexual minority adults from seeking professional help because of the fear that a health professional would judge or mistreat them (Prasad et al., 2022).

Research shows that perceived stress is associated with depression among sexual minorities (Krueger et al., 2018). Additionally, older sexual minorities have a high risk of mental health problems. Almost one-third of older lesbians and gay men (LG) experience major depression at one point (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011). Similarly, other studies also found a high lifetime prevalence of depression among older sexual minorities (Dai & Meyer, 2019). Even so, it is important to note that existing empirical studies on sexual minorities overwhelmingly equate stressors with perceived stress despite their conceptual and operational distinctions. Stressors are sources of perceived stress, whereas perceived stress is a person’s subjective perception and interpretation of the stressors. That is, a stressor becomes stress when a person appraises the stressor as stressful. Additionally, little is known about the levels of perceived stress that stressors actually created even though various stressors do not equally lead to the same stress levels and about the extent to which perceived stress underlies depression. Thus, designing interventions under the assumption that all stressors are equally stressful or spending the same amount of resources on each stressor may be counterproductive.

Forgiveness, Social Support, and Resilience as the Buffers

While dealing with interpersonal and psychological stressors, to buffer the negative impacts of these stressors and subsequent perceived stress, sexual minority older individuals may employ various adaptive coping strategies (Dohrenwend, 2000), such as forgiveness, social support, and resilience. Forgiveness was operationalized by prior research as the framing of a perceived transgression such that one’s thoughts, feelings, or behaviors toward the transgressor or transgression are no longer negative (Thompson et al., 2005). Research suggests forgiveness is an adaptive coping method and is especially salient for older adults (Silton et al., 2013) and stigmatized persons (Vosvick & Dejanipont, 2022). For example, sexual minorities living with HIV—a stigmatized group due to sexual identity and HIV-seropositive status—who tend to forgive others are likely to manage their health self-efficaciously, as they may be less preoccupied with negative thoughts or behaviors toward others, but instead, focus on coping with their health (Vosvick & Dejanipont, 2022). Nonetheless, in addition to the adverse social interactions frequently experienced by older sexual minorities (Meyer et al., 2021) and consequently bitter emotions toward others, negative feelings toward self from, for example, shame about one’s sexual orientation may compile and intensify over time. Subsequently, these accumulating transgressions and emotions may cause mental health problems in older sexual minorities. Indeed, among older people, an inability to forgive is associated with more depressive symptoms (Tian & Wang, 2021). Conversely, self-forgiveness significantly predicts fewer depressive symptoms among gay men (Ünsal & Bozo, 2022). Therefore, forgiveness may be an important adaptive coping strategy for older sexual minorities’ psychological wellbeing because forgiveness may interrupt the adverse impact of stress from negative social exchanges and shame about sexual identity.

Social support is negatively associated with depression among older sexual minorities (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2015). Social support is also associated with positive mental health outcomes and is thought to be a protective factor against sexual minority-related stress (King & Richardson, 2017). However, the relative importance between social support and forgiveness as adaptive coping among older sexual minorities remains unclear. To our knowledge, only two previous peer-reviewed articles examined both forgiveness and social support in a sample related to sexual minorities: Currin and Hubach (2018) found that social support was more crucial than self-forgiveness, whereas Vosvick and Dejanipont (2022) found social support and other-forgiveness have similar importance. In other populations, the results are also mixed (e.g., Weinberg et al., 2017). Therefore, the insights into relative importance between social support and forgiveness as adaptive coping are needed to better understand coping mechanisms employed by older sexual minorities.

Resilience is the ability to face and thrive on adversity (Connor & Davidson, 2003). It is a personal coping resource to manage stressful situations (Masten, 2001) and a protective factor for salubrious mental health (Gralinski-Bakker et al., 2004). For example, McElroy et al. (2016) found resilience moderated the link between stress and depressive symptoms in sexual minority youths. Nonetheless, the researchers failed to find the moderating effect in sexual minority adults and only examined participants who scored high on a depressive symptoms measure. Thus, the role of resilience as a buffer between perceived stress and depression among older sexual minorities is still unclear.

Drawing from research which suggests that forgiveness, social support, and resilience are adaptive coping strategies and that they have an inverse association with depression among sexual minorities (e.g., Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2015; Nakamura & Tsong, 2019; Ünsal & Bozo, 2022), we theorize that these adaptive coping strategies represent distinct aspects of adaptive coping and collectively form a more holistic adaptive coping—which subsequently moderates the link between stress and depression. Notably, while people use a variety of coping strategies in responding to stress and coping strategies are not equally helpful (Vosvick & Dejanipont, 2022), previous studies in sexual minorities have overwhelmingly examined only one adaptive coping strategy per study rather than incorporating multiple adaptive coping strategies.Footnote 1 Thus, while prior research suggests that, for example, social support is important to sexual minorities, the question “Compared to what adaptive coping strategy?” has rarely been directly addressed. Examining only one adaptive coping strategy has created a gap in understanding adaptive coping strategies and their relative importance to sexual minorities from a holistic perspective. Also, insights into the relative importance of different adaptive coping strategies can be useful to policymakers and counselors in their decision-making. For example, although sexual minorities may benefit from both social support-based and forgiveness-based intervention, knowing the relative importance of social support and forgiveness can help counselors decide which intervention to focus on or the order of interventions to implement.

The Present Study

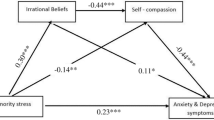

This study examines the extent that different stressors contribute to subsequent perceived stress and the degree to which perceived stress underlines depression as well as the relative importance of forgiveness, social support, and resilience in forming adaptive coping that buffers between perceived stress and depressive symptoms among older LG over 50 years old (50+). Figure 1 shows the proposed model of stressor appraisals and coping. Specifically, we examine the following hypotheses: forgiveness, social support, and resilience significantly form adaptive coping (H1); negative social exchange and shame due to heterosexism significantly predict perceived stress (H2 and H3); perceived stress is a significant predictor of depressive symptoms (H4); and adaptive coping moderates the relationship between stress and depressive symptoms (H5). Structural equation modeling (SEM) is used to test the hypotheses. Unlike multiple regression, SEM allows for inter-relationships between variables to be analyzed simultaneously while accounting for measurement error.

Method

Participants and Procedures

We conducted a power analysis for partial least squares-based SEM (PLS-SEM), using the inverse square root as a conservative method for minimum sample size estimation (Kock & Hadaya, 2018); we set the minimum absolute magnitude of the significant path coefficients to be 0.28 and set the statistical power level and the significance level to be 0.80 and 0.05, respectively. Subsequently, the minimum required sample size was estimated to be 79. The minimum R-squared method also confirmed the power of the sample size. Participants (N = 100) for this study included 50 gay men and 50 lesbians (Table 1); they were demographically similar to sexual minorities in the U.S. in terms of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status, as reported by a nationally representative study (Krueger et al., 2018) and the Public Religion Research Institute (2020). Quota sampling was used to ensure a balanced sampling of lesbians and gay men. Inclusion criteria for this study required participants to be at least 50 years old, fluent in written and spoken English, and identify as a lesbian woman or gay man. Participants were recruited from various LG communities in the southern U.S. through email and fliers. Participants gave written informed consent, completed the research questionnaires on laptop computers, and received a $25 compensation. The research protocol and procedures were approved by the second author’s Institutional Review Board. Table 1 shows the demographic information of the sample, and Table 2 shows correlations of the main variables in the following instruments.

Instruments

Perceived Stress

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983) was administered to measure perceived stress. The PSS includes 14 items (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and ‘stressed’?”; 0 = never, 4 = very often). In this study, composite reliability was 0.84.

Negative Social Exchange

To measure negative social exchange, we used the Test of Negative Social Exchange (TENSE; Ruehlman & Karoly, 1991). The TENSE has 16 items (e.g., “person(s) who currently has an impact in my life was inconsiderate”; 0 = not at all, 4 = about every day) and has four dimensions: hostility/impatience, insensitivity, interference, and ridicule. In this study, composite reliability for the dimensions ranged between 0.85 and 0.89, and that for the overall construct was 0.91.

Shame due to Heterosexism

Shame Due to Heterosexism Scale (SDHS; Dickey-Chasins, 2000) was used to measure shame due to heterosexism. The SDHS includes 11 items (e.g., “I feel disappointed in myself for being gay/lesbian”; 1 = never, 5 = always). Higher scores indicate greater shame about sexual minority identity and community. In this study, composite reliability was 0.81.

Adaptive Coping

Adaptive coping was formed by three distinct coping resources: forgiveness, social support, and resilience.

- 1.

Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS; Thompson et al., 2005) was used to measure the degree of forgiveness. The HFS includes 18 items (e.g., “When someone disappoints me, I can eventually move past it”; 1 = almost always false, 7 = almost always true). In this study, composite reliability was 0.91

- 2.

UCLA Social Support Inventory (UCLA-SSI; Dunkel-Schetter et al., 1986) was used to measure social support. The UCLA-SSI has 40 items (e.g., “How often did your friend understand and empathize with you within the past three months?”; 1 = never, 5 = very often) and includes three types of support: information/advice, aid/assistance, and emotional support. In this study, composite reliability for the dimensions ranged between 0.77 to 0.83, and that for the overall construct was 0.90

- 3.

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC; Connor & Davidson, 2003) was used to measure resilience. The CD-RISC includes 25 items (e.g., “When things look hopeless, I don’t give up”; 0 = not true at all, 4 = true nearly all the time). In this study, composite reliability was 0.96

Depression

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was administered to assess depressive symptoms. The CES-D has 20 items (e.g., “I felt depressed”; 1 = rarely or none of the time, 4 = all of the time). In this study, composite reliability was 0.90.

Data Analysis Plan

All our variables of interest had no missing data. We modeled negative social exchange, shame due to heterosexism, perceived stress, forgiveness, social support, resilience, and depression each as a second-order reflective-reflective construct. Adaptive coping is a third-order reflective-reflective-formative construct that has three second-order constructs: forgiveness, social support, and resilience. Put simply, forgiveness, social support, and resilience were three composite constructs that formed the higher-order construct of adaptive coping. The technical detail about higher-order models or hierarchical component models (HCMs) in SEM is discussed in Hair et al. (2017). We discussed our reasons for the orders of the constructs in detail in Supplemental Material for space reasons.

We conducted PLS-SEM to test the hypotheses. As evident in our power analysis that showed only 79 participants are needed to detect the effect, we selected PLS-SEM instead of covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) because PLS-SEM has higher statistical power for small sample sizes than CB-SEM; also, PLS-SEM is more suitable than CB-SEM when an analysis has a higher-order construct that contains two first-order constructs (Hair et al., 2017) as in our case. Furthermore, PLS-SEM is efficient to handle both reflective and formative measurement models, whereas CB-SEM is efficient to handle mainly formative measurement models (Hair et al., 2017).

We used the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) as the in-sample model selection criteria to test whether our hypothesized model or an alternative model fits the data better. For PLS-SEM, the BIC is a better criterion than the chi-square (Liengaard et al., 2020). Additionally, we used composite reliability as a criterion for internal consistency instead of Cronbach’s alpha, for “Cronbach’s alpha assumes that all indicators are equally reliable (i.e., all the indicators have equal outer loadings on the construct),” whereas composite reliability “takes into account the different outer loading of the indicator variables” (Hair et al., 2016, p. 111). Therefore, composite reliability is more appropriate than Cronbach’s alpha to establish the internal reliability of a construct when using PLS-SEM path modeling. To assess discriminant validity, we used the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) because it is more reliable than cross-loadings and the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Henseler et al., 2015). All analyses were conducted in SmartPLS 3 (Ringle et al., 2015).

To check for differences in the effects on depression based on sexual orientation, we included sexual orientation as a control variable in the model in an ancillary analysis. We found the control variable was insignificant, while the relationship between variables of interest remained significant. Thus, we focus on the model without sexual orientation as a control variable to keep the model parsimonious and report the results for the rest of the study accordingly.

Results

Model Selection

To rule out the potential for an alternative coping process, we ran two models: (1) the hypothesized model with perceived stress and adaptive coping simultaneously explain depressive symptoms and (2) the alternative model with perceived stress initially explains adaptive coping; then, adaptive coping explains depressive symptoms. The results suggested that the hypothesized model was a better predictive model than the alternative (BIC = –97.86 and BIC = –58.95, respectively).

Evaluation of the Measurement Models

The First-Order Reflective Measurement Models

We assessed the validity and internal consistency reliability of each first-order reflectively measured factor or construct. Composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) values of all first-order factors were above corresponding thresholds (0.70 and 0.50, respectively) (Supplemental Material Table S1). Therefore, the results supported the evidence of convergent validity and reliability for the first-order reflective factors. In terms of discriminant validity, the HTMT values for all the pairs of first-order factors were below the 0.90 critical value. Thus, the results indicated that all first-order factors in the model were empirically different from one another and established the evidence of discriminant validity.

The Second-Order Reflective Measurement Model

CR and AVE values of the second-order reflective constructs were well above their corresponding thresholds, suggesting the evidence of internal reliability and convergent validity for the constructs: negative social exchange (CR = 0.91), shame due to heterosexism (CR = 0.81), perceived stress (CR = 0.84), forgiveness (CR = 0.91), social support (CR = 0.90), resilience (CR = 0.96), and depression (CR = 0.90) (Supplemental Material Table S2). To establish discriminant validity between each second-order reflective factor and its first-order factors, we calculated an HTMT value for each of the second-order constructs and found evidence for discriminant validity. Notably, the results supported the evidence that stressors and perceived stress were distinct constructs.

The Third-Order Formative Measurement Model

We examined potential collinearity among the lower-order constructs—resilience (CD-RISC(2rr)), social support (UCLA-SSI(2rr)), and forgiveness (HFS(2rr))—that form the adaptive coping construct (ACOPE(3rrf)) and found no collinearity issues.Footnote 2 Additionally, as hypothesized (H1), the three lower-order constructs of ACOPE(3rrf) were significantly relevant for forming the adaptive coping construct. Notably, forgiveness (ω = 0.37, p < 0.001) was more powerful at forming adaptive coping than social support (ω = 0.15, p < 0.001), while resilience was the most powerful (ω = 0.65, p < 0.001).

Evaluation of the Structural Model

Evaluation of the Simple Effects

Next, we evaluated the structural model without the interaction term. The analyses included (1) testing for potential collinearity for each set of predictor constructs in the model, (2) examining the significance of the path coefficients, and (3) assessing the predictive capabilities of the structural model, including R2 and f2, as recommended by Hair et al. (2016).

Results suggested no collinearity issues for the predictor constructs—TENSE(2rr), SDHS(2rr), PSS(2rr), and ACOPE(3rrf)—as all VIF values were well under the critical value of 5 (Supplemental Material Table S4). Also, the findings indicated that all path coefficients in the structural model were significant. In Fig. 2, standardized coefficient values in brackets refer to the results of the model without the interaction term; values without brackets refer to the results of the model with the interaction term. As Fig. 2 shows, TENSE(2rr) and SDHS(2rr) significantly and positively predicted PSS(2rr); PSS(2rr) and ACOPE(3rrf) predicted CES-D(2rr) in the expected directions.

Models of interaction and simple effects. Note. TENSE(2rr) = negative social exchange; SDHS(2rr) = shame due to heterosexism; PSS(2rr) = perceived stress; ACOPE(3rrf) = adaptive coping; CES-D(2rr) = depression. Standardized coefficients are shown; coefficient values without brackets refer to the results of the model with the interaction term; values in brackets refer to the results of the model without the interaction term; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Additionally, the model showed that TENSE(2rr) and SDHS(2rr) accounted for almost 30% of the variance in PSS(2rr), while PSS(2rr) and ACOPE(3rrf) accounted for nearly 70% of the variance in CES-D(2rr). Moreover, the results suggested that negative social exchange (f2 = 0.21) played more role in predicting perceived stress compared to shame due to heterosexism (f2 = 0.14), and perceived stress (f2 = 0.55) had a large role in predicting depressive symptoms.

Evaluation of the Moderating Effect

We examined the moderating effect of adaptive coping on the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms by analyzing the structural model which included the interaction term. In Fig. 2, standardized coefficient values without brackets refer to the results of the model with the interaction term. The results supported the conclusion that adaptive coping significantly moderated the link between perceived stress and depressive symptoms. Figure 3 shows the visual representation of the moderating role of adaptive coping. Specifically, the magnitude of the relation between perceived stress and depressive symptoms for those with low adaptive coping was significantly stronger than that for those with high adaptive coping.

Discussion

Little is known about the levels of perceived stress that stressors create and about the degree to which the perceived stress underlies depression. Additionally, the literature on forgiveness in sexual minorities is scant, with only one prior study that examined the link between forgiveness and depression among sexual minorities—albeit participants were exclusively young adults (Ünsal & Bozo, 2022). However, research on forgiveness in sexual minorities has potential health implications and theoretical relevance, especially among older populations who have more negative lifetime experiences and tend to look back on their past experiences. Moreover, the relative importance between social support and forgiveness as adaptive coping among older sexual minorities remains unclear. Furthermore, previous studies on sexual minorities have often either narrowly examined adaptive coping or isolatedly examined several forms of adaptive coping; therefore, unaccounting for the complexity of adaptive coping and its multiple levels of abstraction. To address this, the current study examined the relationships among stressors, perceived stress, adaptive coping, and depressive symptoms and concurrently demonstrated the importance of forgiveness and resilience in forming adaptive coping among LG individuals older than 50 years.

Negative social exchange (measured with hostility, insensitivity, interference, and ridicule) and shame due to heterosexism were stressors that were significantly distinct from perceived stress. The two stressors subsequently and significantly predicted perceived stress; negative social exchange was more powerful at predicting perceived stress than shame. Perceived stress, in turn, predicted greater depressive symptoms. Additionally, forgiveness, social support, and resilience each significantly formed adaptive coping. Notably, forgiveness was more relevant in forming adaptive coping than social support, while resilience was the most relevant. Moreover, adaptive coping significantly moderated the link between perceived stress and depressive symptoms. Therefore, compared to social support, forgiveness and resilience are more important in forming adaptive coping, which buffers between perceived stress and mental health problems among older sexual minorities.

Stressors and Perceived Stress

While the prior literature on sexual minorities has identified various forms of negative social interactions as a major stressor, empirical studies have rarely made a clear distinction between the stressor and the experiences of perceived stress. Through the evaluation of the measurement and structural models, this current study established discriminant validity for stressors and perceived stress and showed that stressors predict perceived stress. Moreover, this study’s findings revealed a distinction between stressors. We found the strength of the relationship between negative social exchange and perceived stress was stronger than the one between shame and perceived stress. That is, our finding suggests that distal stressors (e.g., negative social interactions, including hostility, insensitivity, interference, and ridicule) may play a larger role in predicting perceived stress than proximal stressors (e.g., shame about sexual minority identity and community). Latané’s social impact theory may explain this finding. The theory describes three factors that determine the amount of social impact: strength, immediacy, and number (Latané, 1981). Specifically, the strength is “salience, power, importance, or intensity” of the source persons to the target; immediacy is “closeness in space or time and absence of intervening barriers or filters” of the strength of the source persons to the target; and the number is how many source people there are (Latané, 1981, p. 344). The negative social exchange measure that we used, the TENSE, seems to measure the impact factors in Latané’s (1981) social impact theory. Specifically, the TENSE prompts respondents to only “think about every person who currently has an impact” on their lives, rather than the negative interaction with any people in general, and to report “how often each negative interaction occurred with one or more of these important people.” Thus, the type of stressor that the TENSE measures might have contributed to the stronger relationship strength between negative social exchange and perceived stress compared to the one between shame due to heterosexism and perceived stress.

Forgiveness, Social Support, and Resilience as Adaptive Coping

While Currin and Hubach (2018) found in young men who have sex with men that social support was more important than forgiveness as adaptive coping against mental problems, we found that in older LG forgiveness was more important in forming adaptive coping than social support—while resilience was the most important. A possible explanation for the importance of forgiveness in forming adaptive coping could be how forgiveness changes over time. Perhaps, as time passes, unforgiveness becomes more intense for aging sexual minorities who fixate on the past, which subsequently forms maladaptive coping—while the perceived size and importance of social support networks become relatively stable or lessen over time. Consistent with this view, prior work found that among older adults, forgiveness had a higher negative correlation with depressive symptoms than social support had (Tian & Wang, 2021). Therefore, stress from being hurt by others in the past, feeling shame about sexual identity, or feeling guilty about past mistakes may lessen over time for older sexual minorities who can forgive others and themselves. Thus, these sexual minorities may cope with their situation and experience adaptively, as they are not preoccupied or engaged in vengeful behaviors or thoughts.

Moderating Role of Adaptive Coping in Perceived Stress and Depressive Symptoms

As hypothesized, adaptive coping—forming by forgiveness, social support, and resilience—moderated the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms. Notably, as perceived stress increased, adaptive coping became more important to the mental wellbeing of LG50+. At the high levels of stress, LG50+ with high adaptive coping reported a significantly lower frequency of depressive symptoms than those with low adaptive coping. Further, considering the sociopolitical and geographical contexts in southern U.S. states (e.g., Texas), which are relatively more conservative and rural than those in, for example, northeastern states (e.g., New York), one may infer that for older LG living in an urban area or liberal state adaptive coping may be less relevant because sexual orientation diversity tends to be more accepting. However, based on large probability sample studies that show urban sexual minorities experience more mental distress relative to their rural peers (Farmer et al., 2016; Wienke & Hill, 2013), we reasoned that adaptive coping is especially important for the former group. Since experiencing violence by strangers is more likely in urban spaces (e.g., on the street or in gay bars), we speculated that adaptive coping, such as practicing a resilient mindset or forgiving transgressions committed by others without excusing the culprits or offenses, would also be essential for urban older LG and their mental wellbeing.

Implications for Counseling, Practice, and Policy

Our results point to the importance of helping persons develop forgiveness and resilience as adaptive coping because they may be effective in reducing the severity of perceived stress resulting from sources of stress, such as negative social interactions and shame about sexual minority identity. A meta-analysis based on data from randomized controlled trial studies suggests that forgiveness interventions are effective in reducing negative feelings, thoughts, and behavior toward an offender (Akhtar & Barlow, 2018). That is, forgiveness can be developed through evidence-based interventions. Additionally, to protect victims of negative social interactions from further unhealthy relationships, the findings suggest counselors to emphasize to clients “that forgiveness does not necessarily involve reconciliation, condoning, tolerating, or excusing hurtful behavior” (Akhtar & Barlow, 2018, p. 120). Notably, López et al. (2021) and Akhtar and Barlow (2018) discuss a review of forgiveness intervention programs among older populations and those who have experienced negative social interactions, respectively, and interested readers are encouraged to consult their works. Moreover, access to forgiveness interventions should be readily available within mental health settings to promote the mental wellbeing of clients who experienced a range of interpersonal transgressions or negative self-thoughts.

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations of this study should be noted. Our data are subject to response bias, faulty memory, and social desirability, as we used data from self-report instruments despite the effort to reduce social desirability bias by using a confidential computerized survey. While the participants were recruited from northern Texas, they were similar to sexual minorities in the U.S. in terms of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Nonetheless, the sample limits the generalizability of our findings to other older sexual minorities living in other countries. Additionally, the results of this study do not warrant causality because of the cross-sectional nature of our data. Thus, we encourage future researchers to conduct longitudinal studies to examine stressors, subsequent perceived stress, coping, and mental health among diverse samples of sexual minorities over time. Future studies could also examine potentially different dynamics between younger and older sexual minority adults. Additionally, more research on forgiveness as adaptive coping among sexual minorities, especially older adults, is needed to address the significant gap in the literature.

While negative social interactions (measured with hostility, insensitivity, interference, and ridicule) and shame about sexual minority identity and community are uncomprehensive of all stressors that older adults or minority members experience, the proposed model of stressor appraisals and coping processes provides an opportunity for future researchers to use and extend the model to examine both older and minority populations. In addition to examining different types of stressors, examining both adaptive and maladaptive coping approaches may also provide an important understanding of the stressor appraisals and coping processes. Notably, sexual minorities use a variety of coping methods (e.g., Yarns et al., 2016), and how they use a coping method may be different from how straight people use it. For example, compared to older straight adults, sexual minority older adults socialize in person less, while using technology more to socialize (Peterson et al., 2020).

Data Availability

Data is available upon request made to the last author.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

-

The VIF values of the first-order constructs that corresponding to their second-order constructs were well below the threshold value of .5 (Supplemental Material Table S3).

References

Akhtar, S., & Barlow, J. (2018). Forgiveness therapy for the promotion of mental well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(1), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016637079

Chiavaroli, N. (2017). Negatively-worded multiple choice questions: An avoidable threat to validity. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 22(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.7275/ca7y-mm27

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

Currin, J. M., & Hubach, R. D. (2018). Importance of self-forgiveness and social support in potentially reducing loneliness in men who have sex with men. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 12(4), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2018.1526153

Dai, H., & Meyer, I. H. (2019). A population study of health status among sexual minority older adults in select US geographic regions. Health Education & Behavior, 46(3), 426–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198118818240

Dickey-Chasins, H. B. (2000). The development of the Shame Due to Heterosexism Scale (Order No. 9988915). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304600347). https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/development-shame-due-heterosexism-scale/docview/304600347/se-2?accountid=14169

Dohrenwend, B. P. (2000). The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: Some evidence and its implications for theory and research. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676357

Dunkel-Schetter, C., Feinstein, L., & Call, J. (1986). UCLA social support inventory. Unpublished manuscript, University of California, Los Angeles.

Farmer, G. W., Blosnich, J. R., Jabson, J. M., & Matthews, D. D. (2016). Gay acres: Sexual orientation differences in health indicators among rural and nonrural individuals. The Journal of Rural Health, 32(3), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12161

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2020). About Hate Crime Statistics, 2019. https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/2019/topic-pages/incidents-and-offenses

Flanders, C. E., Shuler, S. A., Desnoyers, S. A., & VanKim, N. A. (2019). Relationships between social support, identity, anxiety, and depression among young bisexual people of color. Journal of Bisexuality, 19(2), 253–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2019.1617543

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H. J., Barkan, S. E., Muraco, A., & Hoy-Ellis, C. P. (2013). Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1802–1809. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H.-J., Emlet, C. A., Muraco, A., Erosheva, E. A., Hoy-Ellis, C. P., Goldsen, J., Petry, H. (2011). The aging and health report: Disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Seattle: Institute for Multigenerational Health.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H. J., Shiu, C., Goldsen, J., & Emlet, C. A. (2015). Successful aging among LGBT older adults: Physical and mental health-related quality of life by age group. The Gerontologist, 55(1), 154–168. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu081

Gralinski-Bakker, J. H., Hauser, S. T., Stott, C., Billings, R. L., & Allen, J. P. (2004). Markers of resilience and risk: Adult lives in a vulnerable population. Research in Human Development, 1(4), 291–326. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427617rhd0104_4

Green, K. T., Hayward, L. C., Williams, A. M., Dennis, P. A., Bryan, B. C., Taber, K. H., & Calhoun, P. S. (2014). Examining the factor structure of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in a post-9/11 US military veteran sample. Assessment, 21(4), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191114524014

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage publications.

Hair, J. F., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Kim, H. J., & Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I. (2017). Disparities in mental health quality of life between Hispanic and non-Hispanic White LGB midlife and older adults and the influence of lifetime discrimination, social connectedness, socioeconomic status, and perceived stress. Research on Aging, 39(9), 991–1012. https://doi.org/10.1177/01640275166500

King, S. D., & Richardson, V. E. (2017). Mental health for older LGBT adults. Annual Review of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 37(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1891/0198-8794.37.59

Kock, N., & Hadaya, P. (2018). Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Information Systems Journal, 28(1), 227–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12131

Krueger, E. A., Meyer, I. H., & Upchurch, D. M. (2018). Sexual orientation group differences in perceived stress and depressive symptoms among young adults in the United States. LGBT Health, 5(4), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2017.0228

Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36(4), 343. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.4.343

Liengaard, B. D., Sharma, P. N., Hult, G. T. M., Jensen, M. B., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., & Ringle, C. M. (2020). Prediction: Coveted, yet forsaken? Introducing a cross-validated predictive ability test in partial least squares path modeling. Decision Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12445

López, A., Sanderman, R., Smink, A., Zhang, Y., Van Sonderen, E., Ranchor, A., & Schroevers, M. J. (2015). A reconsideration of the Self-Compassion Scale’s total score: Self-compassion versus self-criticism. PloS one, 10(7), e0132940. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132940

López, J., Serrano, M. I., Giménez, I., & Noriega, C. (2021). Forgiveness interventions for older adults: A review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(9), 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091866

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227

McConnell, E. A., Birkett, M., & Mustanski, B. (2016). Families matter: Social support and mental health trajectories among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(6), 674–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.026

McElroy, J. A., Wintemberg, J. J., Cronk, N. J., & Everett, K. D. (2016). The association of resilience, perceived stress and predictors of depressive symptoms in sexual and gender minority youths and adults. Psychology & Sexuality, 7(2), 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2015.1076504

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer, I. H., Marken, S., Russell, S. T., Frost, D. M., & Wilson, B. D. (2020). An innovative approach to the design of a national probability sample of sexual minority adults. LGBT Health, 7(2), 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2019.0145

Meyer, I. H., Russell, S. T., Hammack, P. L., Frost, D. M., & Wilson, B. D. M. (2021). Minority stress, distress, and suicide attempts in three cohorts of sexual minority adults: A U.S. probability sample. PLoS One, 16(3), e0246827. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246827

Nakamura, N., & Tsong, Y. (2019). Perceived stress, psychological functioning, and resilience among individuals in same-sex binational relationships. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(2), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000318

Peterson, N., Lee, J., & Russell, D. (2020). Dealing with loneliness among LGBT older adults: Different coping strategies. Innovation in Aging, 4(Suppl 1), 516.

Prasad, A., Immel, M., Fisher, A., Hale, T. M., Jethwani, K., Centi, A. J., & Boerner, K. (2022). Understanding the role of virtual outreach and programming for LGBT individuals in later life. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2022.2032526

Public Religion Research Institute. (2020). Broad support for LGBT rights across all 50 states: Findings from the 2019 American Values Atlas. https://www.prri.org/research/broad-support-for-lgbt-rights/

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH, 584.

Ruehlman, L. S., & Karoly, P. (1991). With a little flak from my friends: Development and preliminary validation of the Test of Negative Social Exchange (TENSE). Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 3(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.3.1.97

Salazar, M. S. (2015). The dilemma of combining positive and negative items in scales. Psicothema, 27(2), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.266

Silton, N. R., Flannelly, K. J., & Lutjen, L. J. (2013). It pays to forgive! Aging, forgiveness, hostility, and health. Journal of Adult Development, 20(4), 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-013-9173-7

Song, C., Pang, Y., Wang, J., & Fu, Z. (2023). Sources of social support, self-esteem and psychological distress among Chinese lesbian, gay and bisexual people. International Journal of Sexual Health, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2022.2157920

Szymanski, D. M., & Mikorski, R. (2016). External and internalized heterosexism, meaning in life, and psychological distress. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(3), 265. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000182

Thompson, L. Y., Snyder, C. R., Hoffman, L., Michael, S. T., Rasmussen, H. N., Billings, L. S., & Roberts, D. E. (2005). Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. Journal of Personality, 73(2), 313–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00311.x

Tian, H. M., & Wang, P. (2021). The role of perceived social support and depressive symptoms in the relationship between forgiveness and life satisfaction among older people. Aging & Mental Health, 25(6), 1042–1048. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1746738

U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). Age and sex composition in the United States: 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2022, from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2019/demo/age-and-sex/2019-age-sex-composition.html

Ünsal, B. C., & Bozo, Ö. (2022). Minority stress and mental health of gay men in Turkey: The mediator roles of shame and forgiveness of self. Journal of Homosexuality, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2022.2036532

Van Dam, N. T., Hobkirk, A. L., Danoff-Burg, S., & Earleywine, M. (2012). Mind your words: Positive and negative items create method effects on the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. Assessment, 19(2), 198–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191112438743

Velez, B. L., Moradi, B., & DeBlaere, C. (2015). Multiple oppressions and the mental health of sexual minority Latina/o individuals. The Counseling Psychologist, 43(1), 7–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000014542836

Vosvick, M., & Dejanipont, B. (2022). Behavioral and psychosocial predictors of self-efficacy for managing chronic disease among people living with HIV: Forgiveness, life perspective, and social support. AIDS Care, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2022.2104796

Weinberg, M., Harel, H., Shamani, M., Or-Chen, K., Ron, P., & Gil, S. (2017). War and well-being: The association between forgiveness, social support, posttraumatic stress disorder, and well-being during and after war. Social Work, 62(4), 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swx043

Wienke, C., & Hill, G. J. (2013). Does place of residence matter? Rural–urban differences and the wellbeing of gay men and lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(9), 1256–1279. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.806166

Wight, R. G., LeBlanc, A. J., De Vries, B., & Detels, R. (2012). Stress and mental health among midlife and older gay-identified men. American Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 503–510. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300384

Yarns, B. C., Abrams, J. M., Meeks, T. W., & Sewell, D. D. (2016). The mental health of older LGBT adults. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(6), 60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0697-y

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the review team for their valuable feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the second author’s Institutional Review Board and all procedures were in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dejanipont, B., Wang, C., Jenkins, S. et al. Stressor Appraisals and Moderating Role of Forgiveness, Social Support, and Resilience as Adaptive Coping in Stress and Depression Among Older Sexual Minorities. Sex Res Soc Policy (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00831-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00831-1