Abstract

Positive psychological interventions (PPIs) are activities that target positive variables (e.g., gratitude or kindness) to elicit a positive response in a population, such as improving adaptive functioning, promoting well-being, reducing depression, or enhancing quality of life. Despite several decades of evidence, a meta-analysis by White et al. (2019) concluded that the effect sizes of PPIs may be smaller than previously recorded and that their effects on depression may be generally nonsignificant. In the current study, we created a new PPI, called the Best-Self PPI (BS-PPI), to provide a proof-of-concept of two relatively unexplored properties of PPIs that may enhance effect sizes, which are: (1) combining PPI domains (i.e., multiple targeted positive variables) into a single intervention and (2) designing PPIs to target cognitive mechanisms of change. Using a double-masked procedure, we randomly assigned undergraduate students (n = 133) between the ages of 18 and 32 (Mage = 19.97, SD = 1.66; women; n = 85, 63.9%; White: n = 87, 65.41%) to complete either the BS-PPI – containing elements of meaning, character strengths, and optimism – or a control condition before completing measures of depression, psychological well-being, and affect. One day later, the participants completed a measure of affect and the Self-Referential Encoding Task, a behavioral measure of self-referential processing bias, which is the strength and the valance of the words one uses to describe oneself, to test the potential of targeting a cognitive mechanism of change. One week later, participants completed measures of depression, psychological well-being, and affect. The results suggest the BS-PPI did not affect depression, well-being, or affect compared to the control group despite the consistency of this study with many other PPI studies (e.g., sample size, design, and population), which aligns with the White et al. (2019) meta-analysis. We discuss the implications of this failed proof-of-concept for PPI research and recommendations for moving forward with these relatively unexplored properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Positive psychological interventions (PPIs) are activities designed to cause a positive change in a population by targeting positive variables (e.g., gratitude; Parks and Biswas-Diener, 2013).Footnote 1,Footnote 2 Despite decades of promising findings and support for their efficacy, a recent meta-analysis by White et al. (2019) concluded that the effect sizes of PPIs may be smaller than previously reported for well-being and generally nonsignificant for depression due to small sample size biases. Given these recent concerns about the reliability of the effects of previously developed PPIs, we generated a new PPI, the Best-Self PPI (BS-PPI), to examine two largely untested properties, which were (1) combining domains to potentiate the effect sizes and (2) directly targeting of a cognitive construct. As such, we based the BS-PPI on elements from previous interventions involving optimism (e.g., the Best Possible Self intervention; King, 2001), coherence (e.g., the Life Narrative intervention; Corsten et al., 2015), and character strength (e.g., the VIA Character Strengths Assessment; Niemiec, 2012). No previous PPI has combined three positive variable domains (i.e., according to Gorlin et al., 2018, at most, PPIs target two domains). In addition, we designed the BS-PPI to directly target self-referential processing, an exclusively cognitive mechanism of change concerning the strength and valance of the words one uses to describe oneself (Dainer-Best et al., 2018a). In this proof-of-concept study, we aimed to test if these two unexplored properties of PPIs would result in a significant or larger effect than those found in the White et al. (2019) meta-analysis.

1.1 Combining PPI Domains: Optimism, Coherence, & Character Strengths

Much research has examined PPIs that affect one causal positive variable (e.g., the gratitude letter targets gratitude). Instead, we designed the BS-PPI to target three positive variables: coherence, optimism, and character strengths. A meta-analysis examining the individual effect sizes of many PPI categories reveals that integrating multiple positive variables into PPIs may produce a more substantial effect (Gorlin et al., 2018). For example, the mean effect size for expressing gratitude to others is, Cohen’s d = 0.21. When adding a positive event listing (i.e., a savoring intervention), the mean effect size increases to, Cohen’s d = 0.31. Therefore, it is likely that a more efficacious PPI would include the integration of multiple positive variables (e.g., Lindson et al., 2019); yet this property remains largely untested in the literature beyond two domains (Gorlin et al., 2018). The BS-PPI intervention involved three components, which were (1) using character strengths in a novel manner, (2) finding cohesion and meaning through a personal narrative, and (3) describing and prospecting an optimistic interpretation of the future. These domains are most likely to affect self-referential processing bias, as they involve the positive adjectives one uses to describe oneself. As such, these combined domains may produce a larger effect than single-domain PPIs, and this effect may affect self-referential processing bias.

1.2 Targeting Cognitive Constructs: Self-Referential Processing Bias

Self-referential processing bias is a cognitive construct that involves associating internal and external stimuli with oneself (e.g., identifying with a negative opinion from someone else; i.e., the strength and valance of self-descriptions; Harvey et al., 2011; Kelley et al., 2002). When individuals recall their qualities and have a negatively biased self-referential self-assessment, they are more likely to identify with negative traits and behaviors, potentially leading to depression (Dainer-Best et al., 2018b). Based on evidence suggesting that individuals with depression tend to be high in negative self-referential processing biases, researchers have implicated this cognitive construct in the onset and maintenance of depressive disorders and other forms of psychopathology (Dainer-Best et al., 2018b). In contrast, positive self-referential processing biases may contribute to healthier psychological functioning and well-being. Thus, we designed the BS-PPI to directly target self-referential processing bias. This targeting of a cognitive mechanism generally separates the BS-PPI from previous PPIs, as cognitive mechanisms of change are sparsely examined in the PPI literature. Testing this new property and combining the three domains may reveal new properties of flexibility, applicability, and potency not well-established in the current literature.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

Undergraduate students (n = 133) between 18 and 32 (Mage = 19.97, SD = 1.66) participated in the study for course credit at a Midwestern university. Recruitment occurred online via SONA Systems (https://siuc.sona-systems.com; SONA Systems, Ltd., Tallinn, Estonia) during the 2021–2022 and 2022–2023 academic school years. Participants were primarily women (n = 85; 63.91%), followed by men (n = 43; 32.33%), and then nonbinary (n = 5; 3.76%). Most participants identified as White (n = 87; 65.41%), then Black (n = 34; 25.56%), Latino (n = 18; 13.53%), Asian (n = 3; 2.26%), Pacific Islander (n = 2; 1.50%), and Native American (n = 1; 0.75%). Most of the sample identified as non-Hispanic (n = 114; 85.71%), instead of Hispanic (n = 19; 14.29%). Participant attrition was 14.47%, with 6.92% (n = 11) at Time Two (+1 Day; T2) and 7.55% (n = 12) at Time Three (+ 1 Week; T3). We removed participants who did not follow the instructions (n = 1; 0.63%) or failed the attention checks (n = 2; 1.26%). You can access the data and extended manuscript parts (e.g., extended intervention justification, method section, and discussion) on the OSF at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MBH53.

2.2 Procedure

The current investigation took place over three experimental sessions. At Time One (Baseline; T1), we presented the informed consent. Participants then indicated their age, gender, race, and ethnicity in a demographic form and completed the Positive and Negative Affective Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), and the Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale (RPWBS; Kállay and Rus, 2014; Ryff, 1989). Upon completing these baseline measurements, we randomly assigned participants to complete either the BS-PPI or the control intervention using a double-masked procedure.

We designed the BS-PPI to encourage the participant to examine and savor their good or strong character strengths from the past, present, and future in detail. We delivered the intervention in three writing blocks, one for the past, one for the present, and one for the future. We directed participants to write about a time in the past they used their character strengths, a recent time, and a prospected imagined time about who they want to be in the future. We provided the 24 character strengths from the VIA Character Strengths Assessments for reference (Peterson & Park, 2009; Peterson & Seligman, 2004).Footnote 3 We instructed the participants to use their self-identified character strengths in a novel manner over the next day. Likewise, the control task matched the BS-PPI in many ways without focusing on character strengths, optimism, or coherence. The instructions involved writing about a childhood memory – a common control condition in PPI studies (e.g., Seligman et al., 2005). This study session took place on a computer in a laboratory, was self-directed, and took approximately 30 minutes.

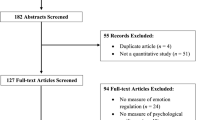

At T2, participants completed the PANAS and the Self-Referential Encoding Task (Dainer-Best et al., 2018a), a behavioral measure of self-referential processing bias. This study session took place on a computer in a laboratory, was self-directed, and took approximately 20 min. At T3, the participants completed the CES-D, RPWBS, and PANAS in a counterbalanced order with attention checks (e.g., select “strongly agree”). The study took place on a home computer, was self-directed, and took approximately 10 min. We ensured that individuals followed the instructions by properly writing about their character strengths and answering instruction-checking prompts (e.g., please describe your experiences using your character strengths over the last day). We removed participants if they failed more than one of the three attention checks (n = 2; 1.26%; see Fig. 1).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Positive and Negative Affective Scales (PANAS)

The Positive and Negative Affective Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) is a 20-item five-point Likert-type scale that measures positive (PA) and negative affect (NA). The PANAS scale has demonstrated excellent factor structures, construct validity, and internal consistency. The internal consistency and factor structure in the current study was good, PA; α = 0.87, Ω = 0.87, NA; α = 0.74, Ω = 0.74, CFI = .925, TLI = .916, RMSEA = .049, p = .201.Footnote 4,Footnote 5

Experimental Session Procedural Flow Chart

Note. Flow chart of procedures across the three timepoints in the study. The initial sample consisted of 159 participants and by T3 the sample was 136, resulting in an attrition rate of 14.47%. We had to remove three additional people for failed attention checks and failure to comply with the instructions, resulting in a final yield of 83.65%

2.3.2 Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

The CES-D measures depression over the last week (Radloff, 1977). Individuals respond to 20 items on a four-point scale. The scale has demonstrated excellent internal consistency estimates ranging from α = 0.85 to α = 0.90 across samples and strong construct validity in the validation study (Radloff, 1977). The internal consistency and factor structure in the current study was good, α = 0.91, Ω = 0.76, CFI = .982, TLI = .980, RMSEA = .043, p = .700.

2.3.3 Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale (RPWBS)

The RPWBS measures psychological well-being (Kállay & Rus, 2014; Ryff, 1989). Individuals respond to 42 items on 7-point Likert-type scales. The scale demonstrated excellent overall reliability of, ω = 0.99, and excellent convergent validity in the original study (Kállay & Rus, 2014; Ryff, 1989). The internal consistency and factor structure in the current study was good, α = 0.92, Ω = 0.72, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .035, p = .994.

2.4 Self-Referential Encoding Task

The self-referential encoding task is a behavioral task designed to measure biases in self-referential processing. We used the task parameters defined by Dainer-Best et al. (2018a, 2018b). We conducted the task on Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com; Qualtrics LCC, Provo, UT, USA). The program presented words one at a time in a random order (i.e., randomized for each participant). The participants used their mice to select if the word described or did not describe them. There was a 1,500 ms pause between each word presentation. The program then instructed the participants to take a break and relax for one minute. During this break, we directed participants to watch a countdown clock. Upon completing the break, the participants had five minutes to recall as many words as possible, which simulates recalling a past event. This memory assessment allows for a more accurate account of the words the participants use in recall rather than initial identification. This method may help reduce any bias a person might have by the initial selection of the words (e.g., a person might say that dirty explains them, but during a recall of events, they do not use such a word to describe themselves; Dainer-Best et al., 2018a). The task took approximately 15 min to complete.

We calculated a d-score to standardize the valance measure of the task. We subtracted the number of positive words recalled for which the participants identified by the number of negative words recalled for which the participants identified. Then, we divided this score by the total number of words recalled for which the participants identified. The final score was a standardized measure of the valance of the participants’ self-referential processing. The scale ranges from -1, which means their recall was entirely negative, to +1, which means their recall was entirely positive. A score of 0 indicates that the recall was evenly positive and negative. One participant (n = 1; 0.63%) did not recall any words and was removed from the analyses.

The task involved 46 words from the Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW) database, which is a standardized database of words with valance, arousal, and frequency of occurrence ratings completed by undergraduates (Bradley & Lang, 1999). The words significantly differed by valance ratings, t(44) = 28.58, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 8.43, and the difference was large between negative words (M = 2.44, SD = 0.61) and positive words (M = 7.45, SD = 0.58). The words did not significantly differ by arousal level, p = .727, frequency, p = .249, or letter count, p = .106. We also included two neutral words at the beginning and end of the list to control for primacy and recent effects (Dainer-Best et al., 2018a, b).

2.5 Analysis Plan

We tested for the effects of the BS-PPI using SPSS 28.0 (IBM Corporation, LLC, Armonk, NY, 2022). To assess for changes in depressive symptoms and psychological well-being, we analyzed the data using a 2 (Timing: Pre-Intervention [T1] vs. Post-Intervention [T3]) by 2 (Intervention: BS-PPI vs. Control) mixed Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). We tested for simple effects, main effects, and interactions. To assess for changes in negative affect and positive affect, we used a 3 (Timing: T1 vs. T2 vs. T3) by 2 (Intervention: BS-PPI vs. Control) by 2 (Affect: Positive Affect vs. Negative Affect) mixed Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). We tested for simple effects, main effects, and interactions. We used pairwise comparisons to test for simple effects using a Bonferroni correction to control for familywise error. Finally, we conducted an independent-samples t-test to demonstrate differences in self-referential processing bias from the intervention.

3 Results

3.1 Preliminary Analyses

We first checked the data for outliers, skewness, and kurtosis of the scale scores, as we did not use the individual items in any analysis. Several variables contained outliers, as defined as two standard deviations away from the mean, which were negative affect at T1 (two outliers), negative affect at T2 (ten outliers), depression at T2 (two outliers), and negative affect at T3 (four outliers), which were all above the mean. However, all outliers were valid cases; therefore, we did not eliminate them from the analyses (Orr et al., 1991). We conducted confirmatory factor analyses of the scales to assess for structural validity and internal consistency. All scales demonstrated good factor structures, observed internal consistencies, and factor-level internal consistencies. An analysis of skewness and kurtosis on the dependent variables revealed no non-normal distributions. Skewness ranged from -0.62 to 2.41, and kurtosis ranged from -1.13 to 6.80. We deleted missing data case-wise (n = 26; 16.35%).

We then examined if we needed to control for demographic variation in our ANOVAs using dummy coded variables. We used independent-samples t-tests and linear regressions with the T1 variables (i.e., depression, psychological well-being, negative affect, and positive affect), and found that no significant demographic variations appeared for gender, ps > 0.164, ethnicity, ps > 0.308, race, ps > 0.229, or age, ps > 0.143. Thus, we did not add any demographic control variables to the analyses.

3.2 Intervention Outcomes

We then tested for changes in depression symptoms, and the results suggested no effects by intervention group, ps > 0.357 (see Fig. 2). The largest effect size by intervention group was, \({{\upeta }}_{\text{p}}^{2}\) = 0.02. Next, we tested for changes in psychological well-being using, and the results suggested no effects by intervention group, ps > 0.280 (see Fig. 3). The largest effect size by the intervention group was, \({{\upeta }}_{\text{p}}^{2}\)= 0.03. Then we examined how the intervention affected negative and positive affect, and the results revealed no significant effects by intervention group, ps > 0.559. The largest effect size by intervention group was, \({{\upeta }}_{\text{p}}^{2}\)= 0.01 (see Fig. 4). Finally, we examined differences in self-referential processing bias from the BS-PPI and found no significant difference, p = .264 (see Fig. 5). The effect size was, Cohen’s d = 0.20. Thus, the effects in the current study were minimal, and we did not find evidence to support their existence outside of this study.

4 Discussion

The lack of group differences between the control and the BS-PPI suggests that the novel PPI properties did not significantly affect depression, psychological well-being, affect, or self-referential processing bias; thus, our proof-of-concept did not support branching out into these properties. Despite the lack of findings in this proof of concept, researchers may consider replicating and extending (1) combinations of domains and (2) targeting cognitive variables in PPI studies because our tested intervention is only one of the hundreds of potential combinations of PPI domains and cognitive constructs. There is still potential for unexplored executions of these novel properties. Still, this lack of findings occurred, despite a meta-analysis of PPI interventions that found that multiple domains of interventions demonstrate small to medium effect sizes on well-being, such as processing positive past events, Cohen’s d = 0.25, optimism, d = 0.36, and strengths identification and novel utilization, d = 0.20 (Bolier et al., 2013). Yet, combining these domains using the same intervention activities resulted in much smaller and nonsignificant effects. This integration sets the BS-PPI apart from many other PPIs, making the lack of an effect notable given the similar sample, sample size, and design to many other PPI studies that find effects (e.g., White et al., 2019). For example, multiple studies have found effects of PPIs after a single computer administration (Cobbs et al., 2017; Stone & Parks, 2018; e.g., best possible self; Boselie et al., 2014; personal, humorous writing; Maiolino & Kuiper, 2016; gratitude letter; Stone et al., 2021), and the use of undergraduates is consistent with many previous PPI studies that demonstrate the effects of brief-duration PPIs (e.g., Altintas et al., 2020; Stone et al., 2021; Stone & Schmidt, 2020, 2022). The only notable difference between this study and other studies that found effects is that (1) our intervention simultaneously used features of optimism, character strengths, and coherence, and (2) we attempted to target a self-referential processing bias. Further, we failed to find significant effects despite some notable strengths of the study, including appropriate sample retention, double-masked random assignment, and a commonly used control condition in PPI studies.

Extraneous factors may have affected the results between our study and other studies finding effects, even though they were held constant within this study (e.g., time of the year, semester in college, age, or rurality). Further, although some studies have failed to find that PPIs affect cognition (e.g., Stone & Schmidt, 2020), some have found that PPIs affect attentional biases (e.g., Stone et al., 2021); yet, it remains unknown if these cognitive elements affected therapy outcomes or other external indicators of improvements. Despite the outcome of this proof-of-concept, there still may be value in combining domains and targeting cognitive mechanisms of change, particularly if the field wants to push for PPIs to be on par with existing interventions that have much more consistent and larger effect sizes. Moving forward, we suggest that researchers select PPIs with large effect sizes to enhance the likelihood of potentiation, given the large possible combinations of PPIs. Further, combing domains and targeting cognitive constructs may unnecessarily complicate the interventions, so selecting PPIs that complement each other well and easily-accessible cognitive constructs may reduce the complexity of the final intervention. Keeping the instructions to a uniform, simple activity, instead of having participants complete seemingly disjointed or complicated interventions, may result in a better experience and larger effect.

5 Conclusion

In the proof-of-concept study, we attempted to test two potential improvements over existing PPI studies by creating a new intervention, the BS-PPI. These novel improvements consisted of combining domains of PPIs into a single intervention and targeting a cognitive mechanism: self-referential processing bias. We hypothesized that these novel properties would potentiate the effects of the intervention. However, we found that the intervention failed to attenuate depressive symptoms, promote psychological well-being, change affect, and positively bias self-referential processing bias at any time. Thus, we did not find proof-of-concept evidence that combining domain PPIs and designing PPIs to target cognitive mechanisms may improve PPI effect sizes. Further exploration of these novel PPI properties may provide more evidence and insight on how researchers can enhance the effects of PPIs.

Data availability

You can access the data and extended manuscript parts on the OSF at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MBH53.

Notes

-

Positive psychological interventions have three criteria that separate these interventions from traditional clinical interventions. First, for an intervention to qualify as a PPI, it must demonstrate efficacy in at least one experiment and have a strong theoretical basis for its effects. Second, PPIs must use a positive variable (e.g., savoring or empathy) instead of targeting strictly negative variables (e.g., negative automatic thoughts). Finally, the change in the positive variables must cause a positive change in the population of interest. For example, increasing gratitude in an undergraduate sample could strengthen positive affect.

-

Despite this consensus on the definition of PPIs, the proposed mechanisms of action, range of positive constructs, intended populations and settings, and cultural influences on the development of PPIs result in significant variability in the interventions – making the term “PPI” a rather broad categorization. Empirical evidence supports the following positive variables, as delineated in the Gorlin et al., 2018 meta-analysis: (1) gratitude, (2) character strengths, (3) goal pursuits, (4) optimism, (5) kindness, and (6) savoring.

-

We did not use the VIA Character Strengths Assessment itself (i.e., the gold-standard multidimensional assessment of character strengths) because the assessment has a fee. To preserve ecological validity with the open-source resources clinicians typically use, generalizability to other studies, and have consistent instructions with other PPIs, we decided to avoid a direct character strengths assessment.

-

We used the weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted estimator (WLSMV; Brauer et al., 2023) in the confirmatory factor analyses to account for the ordinal data and any univariate or multivariate non-normality. We presented the robust versions of the fit indices and provided a range of fit indices for transparency (Stone, 2021, 2023; Hodges et al., 2022).

-

CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index, RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

References

Altintas, E., Karaca, Y., Moustafa, A., & Haj, E., M (2020). Effect of best possible self-intervention on situational motivation and commitment in academic context. Learning and Motivation. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2019.101599. 69.

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Bmc Public Health, 13, 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-119.

Boselie, J. J. L. M., Vancleef, L. M. G., Smeets, T., & Peters, M. L. (2014). Increasing optimism abolishes pain-induced impairments in executive task performance. Pain, 155(2), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.10.014.

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1999). Affective norms for English words (ANEW): Instruction manual and affective ratings. Technical Report C-1, The Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida.

Brauer, K., Ranger, J., & Ziegler, M. (2023). Confirmatory factor analyses in psychological test adaptation and development: A non-technical discussion of the WLSMV estimator. Psychological Test Adaptation and Development, 4, 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1027/2698-1866/a000034.

Cobbs, A. M., Stone, B. M., & Parks, A. C. (2017). The efficacy of happiness interventions: An overview. Quebec Journal of Psychology, 38(1), 159–184. https://doi.org/10.7202/1040074ar.

Corsten, S., Schimpf, E. J., Konradi, J., Keilmann, A., & Hardering, F. (2015). The participants’ perspective: How biographic-narrative intervention influences identity negotiation and quality of life in aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 50(6), 788–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12173.

Dainer-Best, J., Lee, H. Y., Shumake, J. D., Yeager, D. S., & Beevers, C. G. (2018a). Determining optimal parameters of the self-referent encoding task: A large-scale examination of self-referent cognition and depression. Psychological Assessment, 30(11), 1527–1540. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000602.

Dainer-Best, J., Shumake, J. D., & Beevers, C. G. (2018b). Positive imagery training increases positive self-referent cognition in depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 111, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.09.010.

Gorlin, E. I., Lee, J., & Otto, M. W. (2018). A topographical map approach to representing treatment efficacy: A focus on positive psychology interventions. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2017.1342173.

Harvey, P. O., Lee, J., Horan, W. P., Ochsner, K., & Green, M. F. (2011). Do patients with schizophrenia benefit from a self-referential memory bias? Schizophrenia Research, 127(1–3), 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.011.

Hodges, C., Stone, B. M., Johnson, P. K., Carter, J., Sawyers, C. K., Roby, P. R., & *Lindsey, H. (2022). Researcher degrees of freedom in statistical software programs. Behavior Research Methods, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01932-2.

IBM Corp. (2022). IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac. IBM Corp.

Kállay, É., & Rus, C. (2014). Psychometric Properties of the 44-Item version of Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 30(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000163.

Kelley, W. M., Macrae, C. N., Wyland, C. L., Caglar, S., Inati, S., & Heatherton, T. F. (2002). Finding the self? An event-related fMRI study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14, 785–794. https://doi.org/10.1162/08989290260138672.

King, L. A. (2001). The health benefits of writing about life goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(7), 798–807.

Lindson, N., Chepkin, S. C., Ye, W., Fanshawe, T. R., Chris, B., & Hartmann-Boyce, J. (2019). Different doses, durations and modes of delivery of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013308.

Maiolino, N., & Kuiper, N. (2016). Examining the impact of a brief humor exercise on psychological well-being. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 2(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000065.

Niemiec, R. M. (2012). VIA Character Strengths: Research and Practice (the First 10 years). Well-Being and Cultures, 11–29.

Orr, J. M., Sackett, P. R., & Dubois, C. L. (1991). Outlier detection and treatment in I/O psychology: A survey of researcher beliefs and an empirical illustration. Personnel Psychology, 44(3), 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb02401.x.

Parks, A. C., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2013). Positive interventions: Past, present, and future. In T. B. Kashdan, & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being (pp. 140–165). Context Press/New Harbinger Publications.

Peterson, C., & Park, N. (2009). Classifying and measuring strengths of character. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology, 2nd edition (pp. 25–33). Oxford University Press.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press and American Psychological Association.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410.

Stone, B. M. (2021). The ethical use of fit indices in structural equation modeling: Recommendations for psychologists. Frontiers in Psychology: Quantitative Methods, 12, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.783226.

Stone, B. M. (2023). The ethical use of fit indices in structural equation modeling: Recommendations for psychologists. In B. Espejo, M. Martin-Carbonell, & I. Checa (Eds.) Methodological issues in psychology and social sciences research (pp. 4–7). Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/978-2-83250-578-6.

Stone, B. M., & Parks, A. C. (2018). Cultivating subjective well-being through positive psychological interventions. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), The handbook of well-being (pp. 1–12). DEF Publishers.

Stone, B. M., & Schmidt, K. (2020). Positive psychological interventions and cognition. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(5), 629–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1789714.

Stone, B. M., & Schmidt, K. (2022). Integrating Acceptance & Commitment Therapy with positive psychological interventions. European Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 1–9.

Stone, B. M., Lindt, J. D., Rabinovich, N., & Gilbert, D. G. (2021). Effects of the gratitude letter and positive attention bias modification on attentional deployment and emotional states. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00377-2.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

White, C. A., Uttl, B., & Holder, M. D. (2019). Meta-analyses of positive psychology interventions: The effects are much smaller than previously reported. PlOS ONE, 14(5), e0216588. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216588.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Stone would like to thank Dr. Gilbert for all his time and dedication to mentoring Dr. Stone over the last six years of graduate study. The guidance of Dr. Gilbert has substantially contributed to his growth as a professional, researcher, and mentor.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Consent to Participate

We presented, and the participants approved of, an informed consent document at all three-time points.

Consent for Publication

All authors have approved the submission and publication of the current manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g., a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Stone, B.M., Gilbert, D.G. Combining PPI Domains and Targeting Cognitive Mechanisms: A Failed Proof-of-Concept for PPI Research. Int J Appl Posit Psychol 9, 287–300 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00118-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00118-1