Votes, Votes, Votes: Explaining the Long Road to Emigrant Enfranchisement in Ireland

- Department of Government and Politics, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

Enfranchisement of emigrant citizens living outside their home states has been a notable trend in recent decades. While emigrant voting rights are viewed by some as an important part of the wave of suffrage reforms that began in the 1970s, for others they are a contested development that rupture the essence of democracy by breaking the link between citizenship and residence. This article connects insights from the emigrant voting literature with historical institutionalism to argue that the longstanding avoidance of emigrant enfranchisement in the Republic of Ireland was overcome during the Great Recession because of an economic imperative, the need for greater investment from the emigrant community. Diaspora campaigners explicitly linked economic engagement with political rights and the pathway to the policy reform was set. The government gave a commitment in 2017 to hold a referendum to implement the emigrant franchise reform and it is scheduled for 2022, having been initially delayed by the Covid 19 pandemic.

Introduction

Cross-border migration has been transformed by the widespread availability of modestly priced air travel and the ICT revolution that gathered pace from the 1990s. In contrast to earlier generations, migration is both a temporary and a permanent phenomenon but even for those who become long term residents in another jurisdiction, the experience of migration and the ability to retain connections with their home state has been completely altered. Citizens move for short periods of time for study and work and many may live in multiple states over the course of their lives. Because of Web 2.0 technology and digital communication platforms, citizens can remain deeply connected and involved in their home states, using social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) and communication platforms (Zoom, Skype, WhatsApp) to sustain and expand their country of origin networks while building new ones in their states of residence. The image of emigrants, in distant lands, disconnected from their homes, has been consigned to the past. Furthermore, migration continues to expand at considerable pace with the UN reporting that there were 272 million migrants in the world in 2015 (IDEA, 2021: 10).

States began enfranchising their emigrant citizens during the 1970s (IDEA, 2007; Caramani and Grotz, 2015). Fliess and Østergaard-Nielsen (2021) provide a comprehensive evaluation of the development of research on this phenomenon. The extant literature on emigrant voting highlights a series of variables that are instrumental to the expansion of voting rights. These include norm internationalization (Lafleur, 2015; Lisi et al., 2015), democratization reforms in the sending state (LaFleur, and Chelius, 2011), emigrant lobbying and the need to develop and sustain economic connection with migrants (Lafleur, 2011), remittances and country specific dynamics in relation to emigrant groups (Collyer, 2013).

The enfranchisement of emigrants is often a contested reform with some seeing it as changing an essential facet of democracy, the relationship between residence and voting (Honohan, 2011). Ireland is an interesting case to review in the wider context of the enfranchisement of emigrants. It is an old democracy with expansive voting rights. Universal suffrage was enshrined in 1921, all residents in the state are entitled to participate in local elections and United Kingdom citizens living in Ireland have voting rights at parliamentary elections. It falls into a small group of countries including Mexico, Italy, Israel and Croatia that have very large global diasporas yet in contrast to these states, Ireland does not give voting rights to its citizens resident abroad and thus is an outlier, and one worthy of deeper investigation.

Postal voting is highly restricted at elections and only members of the defence forces and civil servants posted abroad (and their spouses) are entitled to a postal vote at Irish elections. Irish citizens, temporarily resident abroad, and planning to return to Ireland within 18 months may travel back to Ireland to vote, at their own expense. These provisions mean that Ireland has among the most restrictive voting rules for its citizens resident outside the state. Despite this, voting rights for citizens abroad made little impact on the domestic political agenda until 2008 when the global economic crisis caused a major rupture in politics and political reform became a substantive consideration, especially at the 2011 general election (Reidy and Buckley, 2017). The central focus of this article is interrogating how emigrant voting rights jumped to the top of a crowded political reform agenda.

The government elected in 2011 referred the question of whether voting rights should be extended to citizens outside the state to a national deliberative forum, the Constitutional Convention. The proposal related to presidential elections only and was strongly supported by the members of the Convention. Ireland is a parliamentary democracy with a directly elected president but the position of president is largely ceremonial and symbolic, thus the enfranchisement proposal is a very small step at what are clearly second order elections. The government accepted the proposal and although, there is some disagreement among lawyers about whether a referendum is required, the government opted for this route, a not untypical conservative approach in relation to constitutional matters. The referendum has been delayed by a number of unforeseen events, especially the Covid 19 pandemic but it currently tops the government’s constitutional agenda.

This article will bring together the analytical lens of historical institutionalism with emigrant voting research to explain the absence of franchise rights for emigrants in Ireland for so long and to explore the role of the economic crisis, conceived as a critical juncture, from 2008 in accelerating policy change. Historical institutionalism emphasises policy continuity while highlighting that crises, especially economic shocks, can present moments of intense contestation and create the potential for shifts in policy direction (Steinmo et al., 1992; Blyth, 2001; 2013; Hay, 2008). Economic considerations and a preference for political engagement with diaspora communities emerge as central motivations from the emigrant voting literature.

The insights from these literatures are combined in the next section to create the explanatory framework for the research. A brief overview of the Irish migration experience and franchise context is provided in section three while section four integrates interviews with political and administrative elites, policy documents, secondary media sources and opinion poll data into the explanatory framework to explain the long avoidance of emigrant enfranchisement and the role of economic crisis in creating a critical moment for electoral reform.

Explaining Emigrant Franchise Reform

Emigrant Voting Literature

Suffrage was built upon the combination of citizenship and residence for much of the 20th century (Honohan, 2011) but increased migratory flows and democratic reforms led to a wave of voting reforms from the 1970s. The voting age was lowered from 21 to 18 in many states (United Kingdom, United States, France, Ireland) while resident non-citizens were also increasingly enfranchised, especially at local elections (Koopmans et al., 2012). But the expansion of emigrant voting rights has been a variable phenomenon as the 2021 IDEA report on out of country voting confirms. The depth and breadth of enfranchisement varies markedly with some countries providing voting rights at all elections for specific classes of citizens residing outside the state (diplomats, the military) while others provide voting rights at specific elections for all citizens resident abroad, and emigrant representation has been built into the political architecture of a small but notable group of states. The arguments for and against emigrant voting rights have been well rehearsed in the literature. Those opposed often start from the point that emigrants are not affected by decisions taken by political representatives elected in their sending states (López-Guerra 2005; Owen 2012) while those in favour argue that all citizens should be treated equally and they take a pluralist view of political rights (Honohan, 2011). It is a political decision to extend franchise rights and research on the emergence of external voting rights identifies a series of variables that have influenced states’ decisions although it is widely concluded that these are not fully generalizable (Collyer, 2014).

Democratization reforms and norm diffusion are emphasised across the literature. Lisi et al. (2015) identify the role of the EU and the Council of Europe in promoting external voting rights in Europe and locate the development in the context of wider norm diffusion. But importantly LaFleur (2015) makes the point that there is no specific legal obligation which requires states to enfranchise citizens resident abroad and domestic democratic reforms such as those undertaken in democratic transitions are also significant in the expansion of emigrant voting rights (see also LaFleur and Chelius, 2011; Caramani and Grotz 2015). Turcu and Urbatsch (2015) note a geographic diffusion effect with neighbouring countries following each other in the adoption of emigrant voting rights.

Domestic politics and electoral competition are central considerations in understanding the motivations that lead governments to consider external voting rights. The historical experience of emigration in a state and perceptions of which political party may benefit from a franchise extension undoubtedly feature in the political calculus of the decision (Collard, 2019; Wellman, 2021). Emigration is often seen in negative terms with an inherent assumption that emigrants were forced to leave a state for political or socio-economic reasons. The timing of waves of emigration and assumptions about which political parties might likely be punished or rewarded by emigrant voters may inform a political decision to proceed with emigrant enfranchisement (Lynch, 2019; Rhodes and Harutunyan, 2010; Bauböck, 2005). Østergaard-Nielsen et al. (2019) show that conservative parties are more likely to favour emigrant franchise extension. In addition to the political preferences of the diaspora vote, the size of the diaspora vote is also a notable consideration with the concept of “swamping” given wide treatment (Honohan, 2011, Hutcheson and Arrighi, 2015).

Stakeholder engagement and specifically lobbying by emigrant groups is notable in many countries that have extended voting rights to emigrants (LaFelur, 2013). Pallister (2020) highlights its centrality in the cases of El Salvador and Guatemala pointing out that it was emigrant lobbying which put the issue on the political agenda and although a strong case, heavily linked to remittance flows was made in both countries, other factors such as norm diffusion were important in the final decision.

And finally, economic interactions between emigrants and their sending state are identified as a central dynamic in the granting of emigrant voting rights in the literature (Erlingsson and Tuman, 2017; Lafleur, 2011; Itzigsohn, 2000). The financial important of remittances in sending states features prominently with a general conclusion that when remittances are a significant factor in the economic life of the state, there is a greater incentive for the state to grant voting preferences to its emigrant citizens (Erlingsson and Tuman, 2017; Sejersen, 2008). But remittances are not the only form of economic connection between sending states and migrants, economic connections may be pursued for wider economic reasons such as tourism, investment and employment. These economic dimensions have received less attention in the literature.

Finally emigrant voting poses a logistical challenge for states. It is both costly and complex as International IDEA has noted (IDEA, 2007; 2021). States which manage the process successfully need to have developed and agile electoral management processes and allocate considerable time and financial supports to the system.

Institutionalism

The literature on emigrant voting provides crucial lessons on the myriad underpinning motivations that lead states toward enfranchising their emigrant citizens but it is less concerned with the confluence of factors that tip a state into acting on external voting rights. Here historical institutionalism can provide valuable insights. Institutionalism is a theoretical lens through which the evolution of political institutions and the development and adaption of public policy can be analysed. The framework emphasises the stability and continuity of institutions and policy making but embedded within the approach are especially effective concepts that can be used to evaluate the role that crises play in providing opportunities for policy change (Streek and Thelen, 2005; Blyth 2013; Hay 2008). Essentially crises can create an opportunity or turning point, known as a critical juncture, when old certainties are questioned and space is created for alternative solutions to emerge (Collier and Collier, 1991).

Bulmer and Burch (2001: 81–82) differentiate between a critical moment and a critical juncture arguing that critical moment arises when there is an opportunity for policy to change but it does not occur whereas they describe a critical juncture as “a clear departure from previously established patterns”. Capoccia and Keleman (2007: 344) argue that critical junctures are disruptions that pertain for short periods of time when the underpinning architecture of decision making is altered allowing a broader set of policy alternatives to emerge. Specifically they discuss a tipping point “at which the cause finally passes a threshold and leads to a rapid change in outcome” (2007: 352). Across the literature, economic crisis is identified as a causation factor for policy change (Steinmo et al., 1992). However, actual change is more likely to occur if there is a confluence of economic, political and administrative viability for the proposed new course of action.

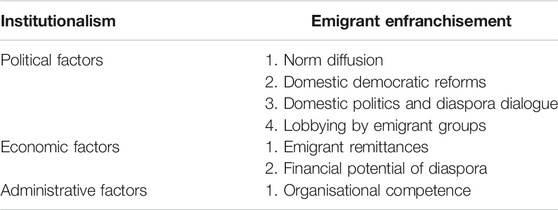

Table 1 provides a mapping of the essential features highlighted in the emigrant voting literature onto the viability dimensions highlighted in the literature on critical junctures.

The Irish case study provides evidence of viability under all three dimensions but the evidence will show that it was economic variables that “tipped” the Irish government into departing from a long ambivalence towards the political rights of emigrants.

The Irish Emigration Experience

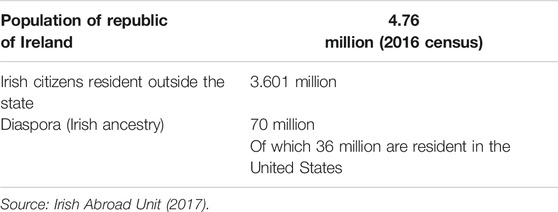

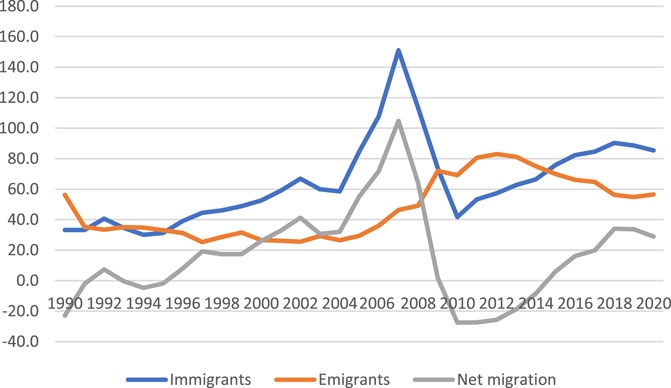

Ireland has one of the largest emigrant communities in the world with a global diaspora estimated to lie between 70 and 80 million people. This includes 36 million Americans who list their ancestry as Irish, or part Irish in the US census (Kliff, 2013; Irish Abroad Unit, 2017). There are also large Irish diaspora communities across the wider Anglophone world especially in the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia. The island has a long history of mass emigration dating back to the 1800s but with particular peaks in the 1840s, 1950s, 1980s and again after 2008 when the global economic crisis particularly impacted the Irish economy. The scale of the most recent emigration wave which began in 2008 is clear from Figure 1. The data includes Irish nationals and foreign nationals, i.e., immigrants includes Irish citizens returning and foreign born arrivals to Ireland, and emigrants includes foreign born residents leaving Ireland as well as Irish citizens.

FIGURE 1. Net migration in Ireland, 1990–2020 Source: Central Statistics Office. Data available at https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/pme/populationandmigrationestimatesapril2020/ (Accessed September 02, 2021).

Eighteen percent of the native born population of the Republic of Ireland lives outside the state (OECD, 2014). The Irish government estimates that presently 3.6 million Irish citizens live outside the state. This figure includes citizens born in Ireland who live abroad, and any of their children/grandchildren who have claimed Irish citizenship. The state operates generous citizenship provisions. The figure also includes the 1.8 million people living in Northern Ireland (part of the United Kingdom) who have an automatic entitlement to Irish citizenship under the terms of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement (1998) (Department of Foreign Affairs, 2017). Importantly for this research, these potential voters are not emigrants, thus external voting rights is a more accurate descriptor of the policy change that is the subject of examination in this work. But emigrant voting rights is the label used by politicians, campaigners and in the media and throughout this paper as a result. Though the figure of 3.6 million is considerably smaller than the global diaspora numbers of 70 million, it still means that Ireland has proportionately among the largest numbers of citizens living outside the state (Statista, 2016). And Ireland is very unusual among large diaspora nations in not enfranchising its external communities. The data are summarised in Table 2.

The arrangements for external voting vary significantly across states. Currently as outlined in the introduction, Ireland has procedures in place to facilitate a small number of state employees living outside the state to vote by post at all elections. Any other voter must return to the state to vote, and even then entitlement is restricted to those who plan to return to live in Ireland within 18 months, although in practice, there is no way, or effort made, to apply this provision.

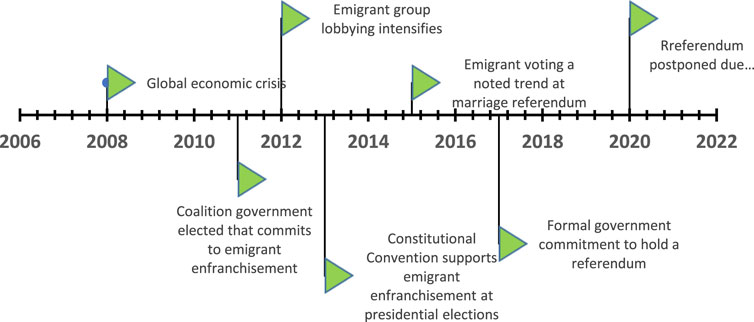

The absence of mechanisms through which Irish citizens living abroad can exercise their political rights has been part of a low key campaign for many decades but it came to greater political prominence in the years after the economic crisis of 2008, often located within the parameters of a broader debate on political reform. Emigrant groups stepped up their lobbying for reform and the government elected in 2011 proposed a restrictive variant of emigrant voting be considered as part of the first national deliberative forum, the Constitutional Convention of Ireland (2012–2014). The Convention supported extending voting rights and the government gave a commitment in 2017 to hold a constitutional referendum to provide for this decision. From a public profile perspective, emigrant voting rights received considerable interest following a surge in emigrants voting (potentially illegally) at social issue referendums in 2015 and 2018 (Farrell et al., 2017; Elkink et al., 2020).

The holding of the referendum was delayed by the Covid 19 pandemic. There are tentative plans for a referendum in 2022 and the commitment to hold referendum to extend voting rights was included in a recently published government strategy document (Diaspora Strategy 2020–2025, 2021). Figure 2 provides a short timeline of the major points in the pathway to the decision to hold the referendum. The central question which emerges from this overview is what changed after 2008 that nudged the then government, and all subsequent ones, towards action on enfranchisement when the issue had been avoided for many decades.

Action on Emigrant Voting

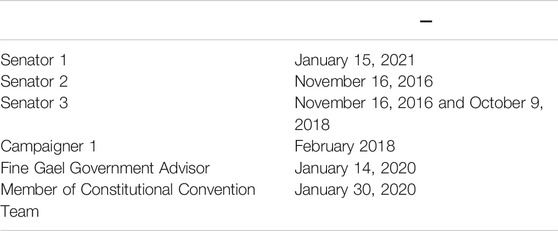

The research presented in this section draws from interviews with a member of the academic advisory panel of the Constitutional Convention of Ireland 2012–14, a senior political adviser to the government, politicians and a member of a campaign groups. The interviews took place between 2016 and 2021 and used open ended questions. Interviews were not recorded but extensive contemporaneous notes were completed for each one. The final interview was conducted via telephone due to the Covid19 pandemic. Table 3 provides summary details of the interviews conducted.

Policy documents published by the Department of An Taoiseach, 2015 and Department of Foreign Affairs are evaluated to demonstrate the evolution of public policy on external voting rights. Finally data from opinion polls are presented in the later analysis to highlight current voting intentions on the upcoming referendum. The evidence from the three main sources are triangulated to inform the analysis which follows the schema developed in section two.

Political Factors

Emigration was a near constant phenomenon in the Irish state until the end of the 20th century. Remarkably though emigration was rarely discussed or remarked upon by political leaders until at least the 1970s. The considerable ambivalence towards emigration and emigrants is probably best captured by JJ Lee in his searing evaluation that “few people anywhere in the world have been so prepared to scatter their children around the world in order to preserve their own living standards” (Lee, 1989). This context is important to understand why emigrant voting rights was an unusually low key political issue in a country with a very large emigrant population. Taking the political factors of norm diffusion, domestic democratic reforms, domestic political conditions and emigrant lobbying identified in the conceptual schema, it is clear that there is some evidence of all four at play but that significant political attention did not arise until at least the start of the 21st century.

Beginning with norm diffusion, Ireland is an old democracy, a member of the European Union and the Council of Europe and a supporter of global democratic standards. Equal voting rights for women and men were enshrined at the foundation of the state in 1921 and like many other states subsequent franchise reforms sought to broaden the base of democracy. Political elites are sensitive to international norms and this is true for its provisions on emigrant voting rights. To cite a recent example, a report by the European Commission in 2014 was critical of the absence of franchise provisions for emigrant Irish citizens (European Commission, 2014). The report prompted a committee of the Irish parliament to investigate the matter. In its response, the Joint Committee on European Affairs recommended that Irish citizens abroad should be enfranchised and it suggested that a national electoral commission was needed to implement the change (Oireachtas, 2014). The absence of provisions for citizens located outside the state to vote is widely acknowledged as unusual among democratic states by political elites across the political spectrum (for an example Seanad Éireann, 2017). While norm diffusion may not have been the driving force behind moves to enfranchise Irish citizens abroad, there is, and was, an awareness that Ireland was unusual among democratic nations in its position.

Emigrant engagement has been part of domestic political debates for some decades. The issue has had variable interest among the main political parties. A Consultation Paper on the Representation of Emigrants was debated in Seanad Éireann (upper house of parliament) in 1996 which proposed that up to three members of the house could be elected by emigrant voters. Holding a referendum was also proposed to enact the change, however the report was not actioned. Unsurprisingly, more nationalist parties tended to embrace emigrant voting rights ahead of others. Fianna Fáil (centre right, moderate nationalist) made a commitment to introduce voting rights in its 1997 manifesto and Sinn Féin (left, strongly nationalist) also became a prominent advocate for change. Interviews with Sinn Féin senators (Senator 2, Senator 3) confirmed that the party views external voting as delivering on two objectives, greater representation for Irish citizens in Northern Ireland and also recognition for the generations of Irish citizens who have left the state because of poor economic conditions. Of the parties, Sinn Féin has the most developed organisational structure outside the state and is widely believed to be most likely to capitalise from any franchise reform. The interviews with Sinn Féin senators confirmed that this is also the internal expectation of the party. But the party support model is more complex, there is broad momentum behind current enfranchisement plans and ministers from the Fine Gael party, traditionally less nationalist in orientation than its competitors, have been among the most vocal supporters (interview with Fine Gael Government Adviser and Senator 1). It was a Fine Gael prime minister, Enda Kenny, that advanced the voting rights proposal and successive Fine Gael ministers have engaged in policy development to advance the issue. Interviews suggested that the issue of voting rights was more salient for politicians from the west coast of Ireland where emigration was much higher, and this was given particular emphasis in relation to the actions of the former Fine Gael prime minister and senior cabinet figures during the 2011–2016 government.

Presidents of Ireland were the first to engage in open dialogue at national level about emigration. Mary Robinson was elected in 1990 and her term in office was noted for providing sustained and meaningful engagement with Irish emigrants and the wider Irish diaspora. Indeed the word diaspora came into common usage during her term in part because of her leadership on the issue (McManus, 2017). In her acceptance speech, she noted “there will always be a light on in Áras an Uachtaráin (residence of the Irish president) for our exiles and our emigrants”. She went on to place a candle in the window of Áras an Uachtaráin as a symbolic act to remember Irish people living abroad. Robinson’s presidency was a transformative point, it was described as causing a “political awakening among the Irish abroad” in one interview with a diaspora campaigner. Subsequent presidents continued and expanded involvement with the Irish diaspora. The current incumbent Michael D Higgins included a representative of the diaspora community on his Council of State (Advisory Committee). Heads of state reaching out to emigrant communities abroad is a common development (Ragazzi, 2009) but while these engagements have grown in number and profile, they remain largely symbolic and initiatives were not connected directly to improving political rights for emigrants.

There has been a long tradition of active Irish emigrant community groups. Welfare, cultural and sporting issues often dominated their list of priorities and when political concerns emerged, they were rarely related to electoral reforms. One senator, also a diaspora campaigner, (Interview with Senator 1) highlighted that it was “dealing with driving licences” for illegal Irish emigrants in the US that drew him into emigrant lobbying. The Northern Irish peace process was a particular priority over many decades. However, a small number of campaigners did promote voting rights reform from the 1990s. Hickman (2016) points to the emergence of Irish Votes Abroad in Australia, the Irish Emigrant Vote Campaign in the United States and a British group Glór an Deorai as evidence of interest among Irish emigrants in franchise reform. But she also highlights a disinclination on the part of successive Irish governments to embrace the issue with constitutional arguments, and taxation and representation issues often raised as reasons why external voting could not be progressed.

A new generation of emigrant voting campaigners joined the political fray in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis. The crisis led to a large wave of outward migration and created a new cohort of young, highly educated Irish emigrants, many of whom viewed emigration as a temporary experience. Votes for Irish Citizens Abroad is a London based campaign group established in 2011 while We’re Coming Back is a social media campaign advocating for voting reform that expects to participate in the forthcoming referendum on voting rights as will VotingRights.ie, and Home2Vote. The latter is a social movement of emigrants who returned to Ireland to vote at the marriage equality referendum in 2015. During interviews, a member of a diaspora campaign group (Interview with Campaigner) stressed that recent Irish emigrants (from 2008) were “especially energised and motivated by social issues and referendum politics rather than party politics”.

There was an unexpected surge in the number of voters from outside the state who returned to Ireland to vote in the marriage equality referendum (Elkink et al., 2017). The Home2Vote hashtag trended on the day of the referendum and the media reported on busy ports and airports as thousands of Irish voters returned to cast their ballots. Not very much is known about these voters but the media consensus was that they were predominantly young and recent emigrants. Emigrant voting was also a feature at the abortion referendum in 2018. The winning margins were large at both of those referendums. Had they been closer results, legal challenges are almost certainly likely to have arisen (Elkink et al., 2020).

To a degree this referendum participation was officially ignored by state actors as election law only allows a citizen to vote if they plan to return to reside permanently in Ireland within 18 months of their initial departure. Clearly some were returning within 18 months but many were not and effectively voted illegally at the referendum. Such mass breaches of the election code could not be tenable in perpetuity and this gave momentum to the developing reform plans for external voting. Importantly, the emigrant community has become directly and actively focused on political rights since the early 21st century.

Democratic reforms in the sending state is a factor emphasised in the emigrant voting literature (Lafleur, 2011; Lafleur, 2015) and while Ireland has strong legal and political rights, the economic collapse in 2008 had major political implications. The economic failings were blamed on poor political institutions and a political culture with an excessive focus on local issues and a terrible track record of long term planning. The first general election after the onset of the economic crisis led to a catastrophic collapse in the vote for the dominant Fianna Fáil party, from which it has not recovered. Proposals for political reform were produced by all of the parties at the 2011 election and the incoming prime minister promised a “democratic revolution” once in office. Emigrant voting rights were included in a long list of promised political reforms. The first step was their inclusion on the agenda of the Constitutional Convention.

The Constitutional Convention of Ireland was the first deliberative citizen’s assembly of this type in Ireland. It was comprised of 33 politicians (from Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland) and 66 randomly selected Irish citizens. The proposal discussed was to give Irish emigrants a vote at presidential elections. There was some surprise that voting rights for emigrants was included on the agenda of the Convention (Interview with Member of the Constitutional Convention Team), although the narrowness of the proposal was at the same time criticized heavily and campaign groups who addressed the Convention argued that a much wider franchise reform should be delivered. However, the Convention was required to adjudicate on the proposal before it and voted overwhelmingly for emigrant voting (78 percent in favour). The government was slow to respond to the outcome and was criticized heavily for its tardiness (Moran and Cantwell, 2014). It had initially agreed to comment on each Convention report within 4 months but this deadline was not met for several of the items addressed. Finally, in 2015, the government reviewed the report and decided that further information was required. An options paper was commissioned and responsibility for the work was allocated to the Minister for Foreign Affairs and the Minister for Housing (responsibility for franchise issues). The paper was published in 2017.

A series of developments took place in the period between the Constitutional Convention vote and the publication of the government options paper in 2017, many of which added impetus to the drive for external voting rights. In 2015, the Government produced a diaspora policy and a government minister for diaspora affairs was appointed for the first time. The interview with the Fine Gael Government Adviser confirmed that these developments stemmed largely from the discussions at the Global Irish Forum (discussed in the next section) and expectations from actors in that network that the diaspora engagement would not be exclusively economic and that political inclusion was expected. Commitments to consider voting rights were also included in the document Global Irish, Ireland’s Diaspora Policy (2015).

Following the rejection of a referendum on abolishing Seanad Éireann (upper house of parliament) in 2013, a review was commissioned to outline reform proposals for the Seanad. The Seanad Working Group Review (known as the Manning Report) included a recommendation that dedicated seats should be set aside in the Seanad for representatives of the Irish diaspora and it proposed that “the principle of one person one vote be extended to include Irish citizens in Northern Ireland and to holders of Irish passports living overseas” (Manning, 2015: 28–30). In the aftermath of the 2016 general election, an internal Seanad working group began work on the specific procedures that should be used for external voting at Seanad elections and it submitted its report to government in December 2018. These recommendations have yet to be actioned. Also in 2016, the prime minister included a representative from the diaspora among his eleven nominees to the upper house. Senator Billy Lawless had been a campaigner for emigrant voting rights and he focused heavily on this issue during his term. In interviews for this research, some members of Seanad Éireann (Senator 1, Senator 2) indicated that they initially interpreted the appointment of Senator Lawless as a tacit endorsement of the proposal to include emigrant representation in any reforms of the upper house but slow movement on those proposals suggest that this view might have overstated the commitment of the government to this initiative.

In March 2017, the government published its options paper on external voting and while on a state visit to the United States for St Patrick’s Day, the prime minister announced that the government intended to proceed with a referendum on extending voting rights to Irish citizens living outside the state at presidential elections. The initial date suggested for the referendum was May 24, 2019. A decision to postpone the referendum was taken in February 2019 and it was announced that the referendum would take place in October. Brexit, lack of administrative preparedness and campaign concerns were all been cited to explain the reasons for the delays (Journal.ie, 2019). Following the election of a new government in early 2020, there was an expectation that the referendum would be the first of a series of votes included in the programme for government. The Covid-19 pandemic led to an immediate pause in the constitutional change plans of the government and the referendum is now expected in 2022.

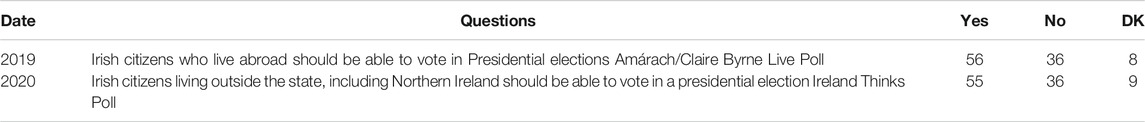

There is a cross party consensus supporting the referendum proposal but only a small amount of data on how the voting public view the proposed change. Very few polls have included questions on the specific referendum question. The most recent opinion poll on the subject from March 2021 reported that 56% of voters favoured the proposal that Irish citizens with valid passports from Northern Ireland should be able to vote in presidential elections and 52% believe that all Irish citizen passport holders should be able to vote in presidential elections (Ireland Thinks, March 2021). Support was strongest among women and also in younger age cohorts. Earlier polls suggest similar support levels as can be seen from Table 4. However, support levels in the low to mid-50s are best understood asmarginal and could be easily eroded in a referendum campaign. Indeed referendums on political reform tend to display high levels of volatility and based on these figures the referendum outcome is very uncertain (see Suiter and Reidy, 2015). In the interview with the Fine Gael Government Adviser it was noted that there were some in government (2011–2016 and 2016–2020 governments) who believed the proposal had little chance of success and in part this contributed to the decision to provide a very limited form of emigrant enfranchisement.

Economic Viability

Turning to economic considerations that have underpinned the change in policy position on emigrant voting rights, the literature emphasises remittances and wider economic engagement. Remittances were a vital source of income for the Irish state from independence and before (O’Grada, 1994) but their importance declined through the later 20th century (Boyle et al., 2016) and remittances sent from Ireland by immigrants had become an area of interest and research by the early years of the 21st century (Maher, 2010).

But the economic dimension of emigration is much wider than remittance networks (Boyle et al., 2016). The global economic crisis of 2008 led to a long and deep recession in Ireland. Unemployment increased sharply and the Irish state entered into a programme of financial assistance with the European Central Bank, European Commission and International Monetary Fund, known as the troika bailout. The scale of the economic crisis resulted in calls for new ideas, and policies on economic management, and engagement with the Irish diaspora was one of the items that was given high priority by the government of the time.

Government attention manifested in a number of initiatives. The Global Irish Economic Forum was established in 2009. It was a meeting of Irish business leaders from Ireland and abroad and the forum programme was initially focused on the economic crisis. Its key objective was to establish ways in which the global Irish community could work more effectively with domestic actors to deliver economic recovery and greater long term prosperity. The forum meets biennially and it has worked on employment conditions, international investment, education and trade policy but importantly its agenda diversified beyond economic issues very quickly. Most especially, as the worst years of the economic recession receded, the political imprint of Irish emigrants both at home and abroad came to be a more prominent consideration. Emigrant voting rights were discussed at several of the forum meetings and a full panel on the topic was included at the 2017 forum. Emigrant voting rights campaigners emphasised that they saw voting rights as a quid pro quo for the economic initiatives proposed by the government.

Government ministers present reiterated their commitment to hold a referendum to extend voting rights for emigrant citizens at presidential elections. An interview with a senior adviser to the prime minister confirmed that the forum was considered an important plank of the economic recovery plan of the government and it was given high importance by relevant ministers and the prime minister who attended each year. The Global Irish Forum differs from the symbolic political engagement led by Irish presidents over several years in that it was focused from the outset and produced concrete outcomes including trade and investment meetings, and very quickly connected economic engagement to wider political rights.

Specific policies and schemes emerged from the focused diaspora engagement. To give some examples, Connect Ireland was an initiative designed to incentivize diaspora business leaders to create job opportunities and it provided financial incentives. The Gathering was a specific tourism initiative during 2013 focused on the Irish diaspora. The idea emerged out of the 2009 Global Irish Economic Forum and was designed to boost tourism numbers during the economic crisis. The initiative included specific plans to hold family reunions, heritage events, clan gatherings and sporting events. It was not without controversy and the initiative was described as a “shake-down” of the diaspora by the Irish actor Gabriel Byrne. His was an important intervention leading to an extended public discussion about how the state engaged with its global community. It led to contributions from key political figures including the president who advocated that the state needed “to have a deeper connection to the diaspora” (Irish Examiner, 2012).

Disentangling the precise motivating factors behind a policy decision is difficult. In interviews with (Senator 1, Senator 3) there was no sense that government was motivated by a belief that voting rights would, in and of themselves, lead to greater economic interest in Ireland by the emigrant community. Rather, interviews suggested that the government and especially the prime minister were persuaded by the political arguments in favour of enfranchisement. However, campaigners effectively connected the two and there was uncomfortable media coverage of the government’s tourism plan. Effective lobbying, especially via the Global Irish Forum is important in helping explain why emigrant enfranchisement reforms were progressed while many other mooted electoral reforms languished in party manifestos. The Global Irish Forum was the first occasion since the foundation of the state that there was structured dialogue with the global Irish community which involved the government, business, cultural and education elites. It was a new departure. Importantly, the focus of the engagement was not exclusively economic, representation and voting emerged early in the discussions as important topics, especially for the Global Irish. It is important that the discussion about economic interactions as an explanation for emigrant enfranchisement is not exclusively focused on remittances and traditional forms of economic dependence. Ireland is an advanced industrial democracy yet it prioritised diaspora engagement as a key strand of its economic recovery plans in the aftermath of the economic crisis. Finally, it is the economic crisis which prompted serious engagement with the Irish diaspora. The Global Irish Economic Forum was funded by the government. Interviews with senators and members of the advisory panel of the Constitutional Convention produced remarkable agreement that the focused engagement would not have occurred in the absence of the economic imperatives generated by the great recession.

Administrative Viability

The provision of emigrant voting rights is a complex process with states using postal voting, in person voting at embassies and consular offices, internet voting and proxy voting as methods to deliver voting (IDEA, 2021). External voting was pitched as administratively challenging in many Irish government responses to lobbying campaigns from the 1990s. As late as 2015, the Diaspora Policy stated “There are also significant practical issues which must be given due consideration.” The Government Adviser interviewed for this research argued this was code for “our administrative structures are not capable of delivering external voting”. Although Ireland is an old democracy with more than one hundred years of continuous free and fair elections, voter registration has been a significant problem for several decades (O’Malley, 2001). There is a general view that election administration is characterised by complacency and policy inertia. Furthermore, many of the broad principles relating to voting rights are set out in the constitution which can only be changed by referendum. This acts as a disincentive to experimentation. The voting age was reduced from 21 to 18 in 1972 but many other efforts to effect change in the electoral arena have failed. Two attempts to change the electoral system (1959 and 1968) and a proposal to reduce the age of candidacy at presidential elections in 2015 were rejected by voters. This has given rise to a degree of hesitancy in relation to electoral reform. This reluctance is also visible in the general administration of elections as well which might be described as moribund.

Undoubtedly, considerable improvements would be required to develop an electoral management system capable of managing external voting. The Manning Report on Seanad Reform (2015), the Seanad Working Group on Reform (2018), the Government Options Paper on External Voting (2017) and multiple reports (particularly from the Constitutional Convention and the Citizen’s Assembly) on other electoral matters all recommended that an electoral commission was a crucial underpinning step in any reforms that would enfranchise citizens living outside the state.

All governments since 2007 have agreed on the need for an electoral commission to improve the management of elections. The establishment of an electoral commission received support from all parties during the term of the 2011–2016 parliament, and several reports recommended that it was essential to improve administration in matters relating to both referendums and elections (Reidy and Suiter, 2015). Resistance to the electoral commission has come from within the administrative system and the Department of Housing, 2017 specifically which is responsible for the administration of electoral processes in particular. But it has now come to an end. In June 2019, the Minister for Local Government and Electoral Reform announced that preliminary work was underway to establish an electoral commission. An interim chief executive has been appointed. The threshold for administrative viability has been passed.

Collectively, political, economic and administrative factors contributed to the final decision to move towards holding a referendum to enfranchise emigrants at presidential elections in Ireland. The campaign for reform dates back 30 years but it was the disruption of the economic recession from 2008 that created the conditions for emigrant voting rights to accelerate up the political agenda and for governments to finally act. The potential for economic investment by the global Irish meant that policy inertia around political rights was quickly overcome.

Conclusion

For almost a century, there was great political ambivalence towards emigrants in the Republic of Ireland. Large economic flows from remittances were not acknowledged in the political arena and emigration was rarely raised as an issue worthy of political reflection. It was not until the 1990s that successive presidents initiated a series of symbolic and substantive engagements. Although remittances declined in importance by the last quarter of the 20th century, the economic imperatives created by the great recession generated a renewed interest in the economic potential of the Irish abroad.

Renewed lobbying and leadership from senior figures in the global Irish community quickly asserted that political rights were a quid pro quo for economic investment. Greater political voice was quickly leveraged for cooperation and the outcome was a political and policy process that led to the referendum proposal due for decision in 2022. Now, Ireland looks likely to join the international movement towards enfranchisement of emigrant citizens. This will be a notable development as Ireland has one of the largest global diasporas and complex citizenship arrangements exist for citizens of the United Kingdom from Northern Ireland who are entitled to claim Irish citizenship.

The Irish case study makes a useful contribution to the literature on the reasons that explain the growing worldwide expansion of emigrant voting rights. It was a conservative leaning political party, Fine Gael that promoted the measure in government and it is widely supported by the other large conservative political party Fianna Fáil and by the strongly nationalist Sinn Féin, a pattern that is consistent with the research on the party types that support emigrant enfranchisement (Østergaard-Nielsen et al., 2019). In line with Collyer and Vathi (2007), the importance of diaspora lobbying and renewed political engagement after the great recession of 2008 are clearly evident. Consistent with Erlingsson and Tuman (2017), Lafleur (2011), Itzigsohn (2000) it finds that economic links were crucial. But it moves the conversation beyond remittances which had long ceased to be a feature of the Irish economy to a wider plane of direct economic investment, tourism, employment and philanthropy, and the financial potential of a global diaspora in these areas. Money matters, and in diverse ways. While lobbying by emigrant groups, diaspora political engagement and norm diffusion were all important in pushing the Irish government to act, importantly it was the economic requirement for investment from the emigrant community which finally overcame political inertia on delivering voting rights. In essence, this article finds that it was the change in economic conditions in Ireland and the deep recession which led policy makers to develop their relationship with the global Irish community. It is probably true to say that if the emigrant “shake-down” wasn’t necessary, progress would not have been made on external voting.

Finally it must be acknowledged that the provision under consideration is a limited one. Although an important symbolic position, the president of Ireland has few direct powers and elections have tended to be infrequent due to a clause which allows an incumbent seek a second term. The referendum is a step towards enfranchisement but it is a very limited form of enfranchisement and hints at an ongoing reluctance to fully engage in the global movement towards greater emigrant enfranchisement. This reluctance may have roots in the complicated structure of the external Irish community and as discussed is also shaped by the need to have a national referendum to progress any change. Political reform referendums have a mixed record with many proposals failing, including those that have been suggested through the national deliberative fora such as the Constitutional Convention.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized interview notes, government reports, poll data and migration statistics can all be made available on request.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The research in this article was carried out as part of the MobilEU project which is funded by the European Union’s (Justice Programme (2014–2020)/Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme (2014–2020)). Grant number: 963348.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bauböck, R. (2005). Expansive Citizenship-Voting beyond Territory and Membership. Apsc 38, 683–687. doi:10.1017/s1049096505050341

Bulmer, S., and Burch, M. (2001). in The rules of integration: Institutionalist approaches to the study of Europe. Editors G. Schneider, and M. Aspinwall (Manchester: Manchester University Press).The Europeanisation of central government: The UK and Germany in historical institutionalist perspective

Capoccia, G., and Kelemen, R. D. (2007). The Study of Critical Junctures: Theory, Narrative, and Counterfactuals in Historical Institutionalism. World Pol. 59, 341–369. doi:10.1017/s0043887100020852

Caramani, D., and Grotz, F. (2015). Beyond citizenship and residence? Exploring the extension of voting rights in the age of globalization. Democratization 22, 799–819. doi:10.1080/13510347.2014.981668

Collard, S. (2019). The UK Politics of Overseas Voting. Polit. Q. 90, 672–680. doi:10.1111/1467-923x.12729

Collyer, M. (2014). A geography of extra-territorial citizenship: Explanations of external voting †, 2, 55–72. doi:10.1093/migration/mns008

Collyer, M., and Vathi, Z. (2007). Patterns of extra-territorial voting. Development Res. Centre Migration, Globalisation Poverty Working Paper 22, 1–36.

Department of An Taoiseach (2015). Global Irish: Ireland’s Diaspora Policy. Dublin: Stationary Office.

Department of Housing (2017). “Planning, Community and Local Government and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade,” in Voting at Presidential Elections by Citizens Resident Outside the State (Dublin: Stationary Office).

Elkink, J. A., Farrell, D. M., Reidy, T., and Suiter, J. (2017). Understanding the 2015 marriage referendum in Ireland: context, campaign, and conservative Ireland. Irish Polit. Stud. 32, 361–381. doi:10.1080/07907184.2016.1197209

Erlingsson, H., and Tuman, J. P. (2017). External Voting Rights in Latin America and the Caribbean: The Influence of Remittances, Globalization, and Partisan Control. Latin Am. Pol. 8, 295–312. doi:10.1111/lamp.12125

European Commission (2014). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Addressing the Consequences of Disenfranchisement of Union Citizens Exercising Their Right to Free Movement/* Com/2014/033 Final */. Brussels. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52014DC0033&from=EN.

Fliess, N., and Østergaard-Nielsen, E. (2021). Extension of Voting Rights to Emigrants. Oxford Bibliographies. Available at https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756223/obo-9780199756223-0335.xml#obo-9780199756223-0335-bibItem-0008.

Hickman, M. (2016). Why has Ireland to date resisted the demands from citizens abroad to end their disenfranchisement? History Ireland, 24(3)

Honohan, I. (2011). Should Irish Emigrants have Votes? External Voting in Ireland. Irish Polit. Stud. 26, 545–561. doi:10.1080/07907184.2011.619749

Irish Abroad Unit (2017). Dublin. https://www.dfa.ie/media/dfa/alldfawebsitemedia/newspress/publications/ministersbrief-june2017/1–Global-Irish-in-Numbers.pdf.Irish Emigration Patterns and Citizens Abroad

Irish Examiner (2012). President defends Gabriel Byrne's criticism of The Gathering. https://www.irishexaminer.com/breakingnews/ireland/president-defends-gabriel-byrnes-criticism-of-the-gathering-575083.html.

Koopmans, R., Michalowski, I., and Waibel, S. (2012). Citizenship rights for immigrants: National political processes and cross-national convergence in Western Europe, 1980–2008. Am. J. Sociol. 117 (4), 1202–1245.

Lafleur, J.-M., and Chelius, L. C., (2011). Assessing Emigrant Participation in Home Country Elections: The Case of Mexico's 2006 Presidential Election, 49, 99–124. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00682.x

Lafleur, J.-M. (2015). The enfranchisement of citizens abroad: variations and explanations. Democratization 22, 840–860. doi:10.1080/13510347.2014.979163

Lafleur, J.-M., (2011). Why Do states enfranchise citizens abroad? Comparative insights from Mexico, Italy and Belgium, 11, 481–501. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2011.00332.x

Lafleur, J. M. (2013). Transnational politics and the state: The external voting rights of diasporas. UK: Routledge.

López-Guerra, C. (2005). Should Expatriates Vote?*. J. Polit. Philos. 13, 216–234. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2005.00221.x

Maher, G. (2010). A transnational migrant circuit: Remittances from Ireland to Brazil. Irish Geogr. 43, 177–199. doi:10.1080/00750778.2010.500891

McManus, J. (2017). Taoiseach blows out Mary Robinson’s light. Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/john-mcmanus-taoiseach-blows-out-mary-robinson-s-light-1.3014719.

Moran, O., and Cantwell, S. (2014). Why has the Government ignored the Irish diaspora – again. TheJournal.ie. https://www.thejournal.ie/readme/right-to-vote-irish-emigrants-1382597-Mar2014/.

O'Malley, E. (2001). Apathy or error? Questioning the Irish register of electors1. Irish Polit. Stud. 16, 215–224. doi:10.1080/07907180108406641

Ó’Gráda, C. (1994). The economic development of Ireland since 1870. Edward: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Oireachtas Éireann (2014). Report of the Joint Committee on European Affairs on the Voting Rights of Irish Abroad.Available at. Dublin. https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/press-centre/press-releases/20141113-eu-affairs-committee-calls-for-voting-rights-of-irish-abroad/.

Østergaard-Nielsen, E., Ciornei, I., and Lafleur, J.-M. (2019). Why Do parties support emigrant voting rights. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 11, 377–394. doi:10.1017/s1755773919000171

Owen, D. (2012). Constituting the polity, constituting the demos: on the place of the all affected interests principle in democratic theory and in resolving the democratic boundary problem. Ethics Glob. Polit. 5, 129–152. doi:10.3402/egp.v5i3.18617

Pallister, K. (2020). Migrant populations and external voting: the politics of suffrage expansion in Central America. Policy Studies, 41. 2–3.

Ragazzi, F. (2009). Governing diasporas. Int. Polit. Sociol. 3, 378–397. doi:10.1111/j.1749-5687.2009.00082.x

Reidy, T., and Buckley, F., (2017). Democratic revolution? Evaluating the political and administrative reform landscape after the economic crisis, 65, 1–12. doi:10.1515/admin-2017-0012

Rhodes, S., and Harutyunyan, A. (2010). Extending citizenship to emigrants: democratic contestation and a new global norm. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 31 (4), 470–493.

Seanad Éireann, (2017). Statements on the Diaspora. No. 3. (Available at https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/seanad/2017-11-14/10/?highlight%5B0%5D=irish&highlight%5B1%5D=nation&highlight%5B2%5D=irish&highlight%5B3%5D=nation&highlight%5B4%5D=citizenship&highlight%5B5%5D=irish&highlight%5B6%5D=nation&highlight%5B7%5D=irish&highlight%5B8%5D=citizenship.254

Sejersen, T. B. (2008). "I Vow to Thee my Countries" - The Expansion of Dual Citizenship in the 21st Century. Int. Migration Rev. 42, 623–649. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2008.00136.x

S. Steinmo, K. Thelen, and F. Longstreth (Editors) (1992). Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis (New York: Cambridge University Press).

Suiter, J., and Reidy, T. (2015). It's the Campaign Learning Stupid: An Examination of a Volatile Irish Referendum. Parliamentary Aff. 68, 182–202. doi:10.1093/pa/gst014

Wellman, E. I. (2021). Emigrant Inclusion in Home Country Elections: Theory and Evidence from sub-saharan Africa. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 115, 82–96. doi:10.1017/s0003055420000866

Keywords: emigrant voting, enfranchisement of overseas voters, Irish elections, franchise reform, diaspora, referendum

Citation: Reidy T (2021) Votes, Votes, Votes: Explaining the Long Road to Emigrant Enfranchisement in Ireland. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:722444. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.722444

Received: 08 June 2021; Accepted: 15 October 2021;

Published: 05 November 2021.

Edited by:

Johanna Peltoniemi, University of Helsinki, FinlandReviewed by:

Pau Palop Garcia, University of Erfurt, GermanyMiroslav Nemčok, University of Oslo, Norway

Copyright © 2021 Reidy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Theresa Reidy, t.reidy@ucc.ie

Theresa Reidy

Theresa Reidy