- Center for Educational Science and Technology, Beijing Normal University, Zhuhai, China

Introduction: Although the relationships between parental mental health and child internalizing and externalizing problems have been explored by previous studies, the pathways between these two variables need further exploration. The present study aims to explore the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems and to examine the roles of parenting stress and child maltreatment in those relationships within the Chinese cultural context.

Method: Data were collected from 855 Chinese families with preschool-aged children, and mediation analysis was used to examine the pathways between these variables.

Results: The results show that parental depression is positively associated with child internalizing and externalizing problems, and child maltreatment and the combination of parenting stress and child maltreatment mediated the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, respectively. These findings suggest that parental depression not only has a direct effect on child internalizing and externalizing problems but also has an indirect effect via parenting stress and child maltreatment.

Discussion: Decreasing the levels of parenting stress and child maltreatment should be applied in interventions to break the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems within the Chinese cultural context.

Introduction

Internalizing and externalizing problems, including maladaptation in emotions and behaviors, are important issues in child development, particularly in children of preschool age (1), but they also have long-term effects on later behavioral, emotional, and social development (2, 3). Approximately 20% of Chinese preschool-aged children have internalizing and externalizing problems (4), and several factors increase the risk of these problems, such as parental depression (5). Parents with high levels of depression may increase the levels of internalizing and externalizing problems in children (6). However, there is little knowledge about the pathways between these two variables. Parents who have high levels of depression may pay attention to negative events (7), which may increase their parenting stress, and these high levels of parenting stress may increase the risk of child maltreatment (8), which, in turn, contributes to child internalizing and externalizing problems (9). According to Goodman and Gotlib (10), the context, particularly the stressors, of the lives of children in families with depressed mothers, contributes significantly to the development of psychopathology in children. Guided by this notion and by the family system theory that emphasizes that the family is a complex emotional unit and family members influence each other (11), the current study attempts to verify the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems and to examine the mediating factors (e.g., parenting stress and child maltreatment) of those relationships.

Parental depression, internalizing and externalizing problems, and parenting stress

A growing body of research has shown that parental depression is positively associated with children internalizing and externalizing problems. Based on a cross-sectional study with 2222 Chinese parents, Ma et al. (12) reported that parental depression was positively associated with internalizing and externalizing problems of preschool-aged children. Zong et al. (13) confirmed these results based on a longitudinal study with Chinese samples. Moreover, Marçal (14) found that parental depression positively predicted child internalizing and externalizing problems based on a longitudinal study with Western samples. Parents with depression may have high levels of marital conflicts (15) and hostile parenting methods (16), contributing to high levels of child internalizing and externalizing problems (17). Additionally, according to the model of relationships between depressed mothers and child development discussed by Goodman and Gotlib (10), depressed parents may cause impairments in their child's later development.

Although large extensive research has confirmed the relationships between parental depression and internalizing and externalizing problems in children across nations and cultures, the pathways between these two variables still need further exploration. Parenting stress, an index for levels of stress in parenthood, might be a factor in the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Parents with high levels of depression may have high levels of parenting stress, namely in new parents (18, 19), and Galbally et al. (20) confirmed these results in a longitudinal study with 246 Australian parents of toddlers. Meanwhile, Salloum et al. (21) reported on these relationships among parents of children aged 8–12 years old. Those relationships have also been confirmed in parents of adolescents with Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder (22).

Moreover, parenting stress predicts if a child will later develop internalizing and externalizing problems, as seen in previous studies (23, 24). For example, based on a Chinese cross-sectional study, Li et al. (25) reported that parenting stress was positively associated with internalizing and externalizing problems of 317 preschool-aged children. Based on a longitudinal study, Han amd Lee (26) found that parenting stress positively predicted 1724 Korean preschool-aged children's internalizing and externalizing problems. Meanwhile, also based on a longitudinal study, Kochanova et al. (27) found these relationships in 1209 American children in early childhood, and de Maat et al. (28) also confirmed those relationships based on a study conducted with 441 European adolescents and their parents.

Even though the associations between parental depression, child internalizing and externalizing problems, and parenting stress have been explored by extensive research, few studies have explored the roles of parenting stress in the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, particularly in children of preschool age. Parents with high levels of depression may have attention biases to negative information (29), which may increase parenting stress (30), and, finally, contribute to child internalizing and externalizing problems (31). Thus, we hypothesize that parenting stress mediates the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems within the Chinese cultural context.

Parental depression, internalizing and externalizing problems, and child maltreatment

Child maltreatment, including negative parenting behaviors, has been explored in extensive studies, and parental depression may be a risk factor for child maltreatment (32). David (33) found that 62% of parents who have maltreated their children had mental health problems (e.g., depression). Based on a longitudinal study with 1,813 families, Mustillo et al. (34) reported that parental depression positively predicted child maltreatment in children aged 0 to 14. Plant et al. (35) found that parental depression alone did not predict child maltreatment, but the combination of parental childhood maltreatment and depression predicted child maltreatment.

Moreover, the relationships between child maltreatment and child internalizing and externalizing problems have been explored by previous studies. Based on a longitudinal study, Isumi et al. (36) found that child maltreatment positively predicted later internalizing and externalizing problems in Japanese children aged 6 to 10. Watters et al. (37) reported that, based on a longitudinal study, child maltreatment positively predicted later internalizing and externalizing problems in 1067 American adolescents. Ma et al. (38) confirmed these results in a study with 2180 South Korean adolescents. However, Godinet et al. (39) did not find a relationship between child maltreatment and internalizing and externalizing problems among preadolescent girls.

Although associations between parental depression, child internalizing and externalizing problems, and child maltreatment have been explored by extensive research, few studies have explored the role of child maltreatment in the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Moreover, depressed parents may cause negative attributions in child behaviors (12), which may increase the risk of negative parenting behaviors, such as maltreatment behaviors. Thus, we hypothesize that child maltreatment mediates the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems within the Chinese cultural context.

Parenting stress and child maltreatment

Parenting stress may be a risk factor for child maltreatment (40), and the relationship between these two variables has been explored by previous studies. For example, Crouch et al. (41) found that parents who have high levels of parenting stress had three times the risk of maltreating their children than parents with low levels of parenting stress. Maguire-Jack and Negash (42) reported that parenting stress positively predicted child maltreatment in 1045 American families.

Although previous studies have explored the separate roles of parenting stress and child maltreatment in the relationship between parental characteristics and child development, few studies have examined the roles of the combination of parenting stress and child maltreatment in those relationships. We hypothesize that parenting stress and child maltreatment progressively mediate the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems.

The current study

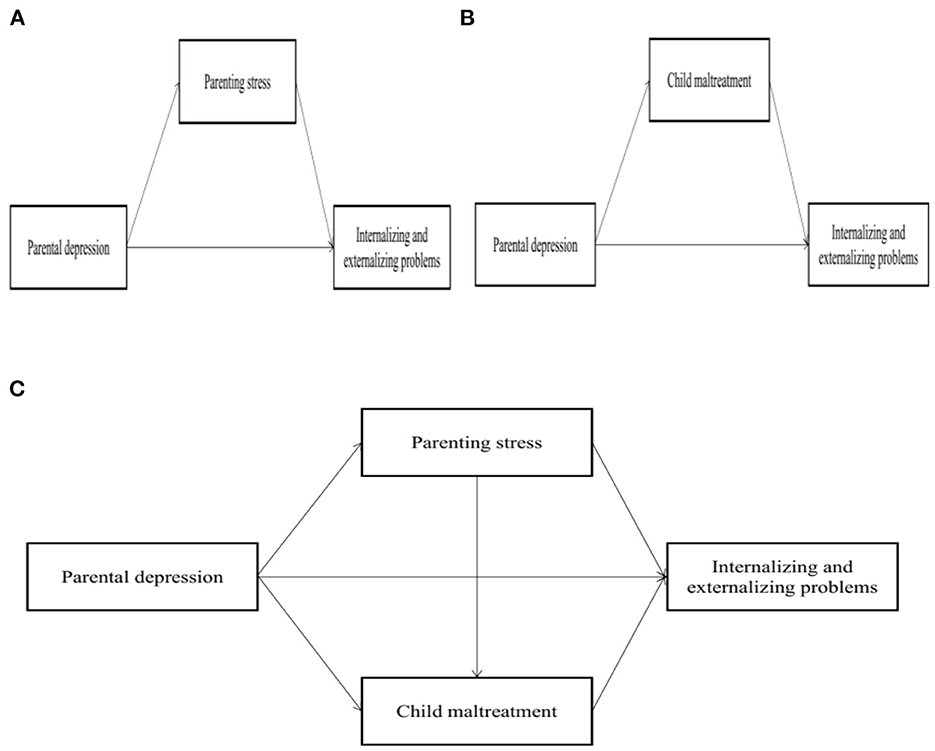

Although previous studies have explored the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, few studies have examined the roles of parenting stress and child maltreatment in those relationships, particularly in Chinese families with preschool-aged children. China, an ancient Eastern country, has a long history of endorsing Confucian culture, which may influence the values, thinking patterns, and beliefs of the modern Chinese population. Traditional Chinese culture emphasizes the importance of children in families [e.g., Wang Zi Cheng Long highlighted the hope within families that children have a bright future) and harsh discipline for educating children (e.g., physical punishment; (43)], which may increase parenting stress and negative parenting behaviors. Thus, parenting within the Chinese cultural context may be different from Western countries, which may raise the importance of exploring these issues within the Chinese cultural context. Moreover, environmental factors (e.g., COVID-19) may also influence parental mental health, which may increase the risks of parenting stress and child maltreatment, and contribute to maladaptation in child development. Therefore, the current study attempts to verify the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems and to examine the roles of parenting stress and child maltreatment in Chinese families with preschool-aged children. We hypothesize that parenting stress and child maltreatment play a mediation role in the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, respectively, as well as the combination of parenting stress and child maltreatment (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Hypotheses models. (A) model: Parenting stress model; (B) model: Child maltreatment model; (C) model: The combination of parenting stress and child maltreatment model.

Methods

Participants

The project of ability and nurture in dreaming age (PANDA), a Chinese longitudinal study with a six-month interval, aimed to explore the relationships between external environment factors (e.g., family, school, and community) and individuals' development from preschool to middle school within the Chinese cultural context. The PANDA initially recruited 900 families from five preschools in South China, and 45 families dropped out during the data collection process. The current study used the data of Wave 1 in PANDA, which was collected in May 2021. In 855 families, 15.8% (135/855) of fathers completed the survey, and all of the parents had married within five years of the survey date (3 years: 11.5%; 4 years: 29.9%; 5 years: 58.6%). For family monthly income, 0.8% of the families were below 2500RMB ($368.25), 2.5% fell into the range from 2500RMB to 5000RMB ($736.5), 12.9% fell into the range from 5001RMB to 10,000RMB ($1,473), 56.1% fell into the range from 10,001RMB to 30,000RMB ($4,419), and 27.6% of the families earned above 30,000RMB (the median income in the geographical area of the study was 8,832 RMB). Moreover, the mean children's age was 4.55 years (SD = 0.85), with a range from 3 to 6 years, and 52.2% (446/855) of the children were boys.

Measures

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a self-report scale with 20 items that was developed by Radloff (44) with the aim of assessing levels of depression in daily life. Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = rarely or<1 day” to “4 = most of the time,” and high scores indicate high levels of depressive symptoms. Wang et al. (45) translated and validated the CES-D to the Chinese cultural context, and the Chinese version of the CES-D has been widely used to assess depression in Chinese samples (46). The Chinese version of the CES-D was administered to assess parental depression in the current study, and had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.88.

The Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) is a self-report questionnaire with 36 items that was developed by Abidin (47) with the aim of measuring levels of parenting stress. The PSI-SF has three subscales, including parenting distress (e.g., feel alone and without friends), dysfunctional interaction (e.g., most times feel that child does not like me), and difficult child (e.g., my child generally wakes up in a bad mood), which measure different aspects of parenting stress. Each item is rated based on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree,” with higher scores indicating high levels of parenting stress. The Chinese version of the PSI-SF has good reliability and validity (48), and it was administered in the current study with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.94.

The ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tools Parents Version (ICAST-P) is a self-report screening tool developed by Runyan et al. (49) that has been used to measure child maltreatment across nations and cultures (50). Chen et al. (51) translated and validated the ICAST-P to the Chinese cultural context, and the Chinese version of the ICAST-P has 40 items and acceptable reliability and validity. The Chinese version of the ICAST-P has 5 subscales, including moderate physical discipline (12 items; e.g., Shook him/her aggressively), severe physical discipline (5 items; e.g., Burned him/her), emotional discipline (12 items; e.g., Shouted at him/her), neglect (5 items; e.g., Your child was not given food to eat), and non-violent discipline (6 items; e.g., Explained to him/her why something s/he did was wrong). Participants respond to each item via a six-point scale (0 = never and not in the past year; 1 = once or twice a year; 2 = several times a year; 3 = about once a month; 4 = several times a month; and 5 = once a week or more often), and high scores indicate high levels of child maltreatment. The Chinese version of the ICAST-P was administered in the current study to measure child maltreatment, and had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.90.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a self-report questionnaire with 25 items that was developed by Goodman (52) with the aim of measuring the mental strengths manifested in children and the difficulties faced by the children. It has five subscales, including subscales of emotional symptoms (e.g., Many worries, often seems worried), conduct problems (e.g., Often lies or cheats), hyperactivity (e.g., Thinking things out before acting), peer problems (e.g., Rather solitary, tends to play alone), and prosocial scale (e.g., Kind to younger children). Participants respond to each item via a three-point scale (1 = “not true,” 2 = “somewhat true,” and 3 = “certainly true”), and high scores indicate high levels of mental strengths and difficulties. The Chinese version of the SDQ has good reliability and validity (53, 54), and subscales of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems were administered to measure internalizing and externalizing problems of children in the current study, and the Cronbach's alpha of the total four subscales was 0.71.

Procedure

The authors presented the aims and processes of this study to five preschool headmasters and received their permission to conduct the current study in their preschools. A total of 855 parents from different families signed the informed consent at the beginning of the data collection process and finished the questionnaire booklets within 15 min in the classrooms. Teachers and parents who participated in the study received a small gift ($1), and parents also later received feedback that delineated the current development situation of their child. Concerning the feedback, it did not contain variables of this study, which may not affect the results of this study. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the author's institution, and the procedures and measures of the current study were safe for participants.

Data analysis

The current study used several steps to perform the data analysis. First, the author cleaned and prepared the data. For example, the author cleaned the data by removing the outliers (25/900) who completed the questionnaires with the same answer except for the demographic questionnaires, and participants (20/900) who finished the questionnaire in < 350 seconds and provided wrong answers for all detecting questions (e.g., please choose “3”). Then normality was examined, and the average scores were computed for each scale, and prepared for the next steps.

Second, the Pearson correlation was conducted to analyze the correlations between variables, and also to examine whether the mediation analysis was suitable for further analysis or not. The data is considered suitable for mediation analysis if the coefficients of pairwise correlations are significant among study variables (55).

Third, mediation analysis is a method to explore the roles of one or more than one variable in relationships between other two variables, which may explain the pathways or mechanisms underlying variables. The current study used mediation analysis to explore the relationships between parenting depression, child internalizing and externalizing problems, parenting stress, and child maltreatment. A direct model was conducted to delineate the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, then a serial mediation model was conducted to delineate the roles of parenting stress and child maltreatment in the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems. All statistical analyses were conducted by R language version 4.1.2 with bruceR packages. A PROCESS (model 6) function with maximum likelihood estimation was used to explore the serial mediation model. Moreover, the Bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method was used to examine the 95% confidence interval (CI) of mediation effects of 1,000 samples. If the 95% CI of the indirect effect contains 0 it means that the indirect effect exists, and if the 95% of the direct effect contains 0 it means that the variable plays a full mediation role in the study variables. All tests were two-tailed for significance, and the p-value was set at 0.05. Additionally, the current study used digital questionnaires to collect data, and there were no missing data for all variables.

Results

Descriptive statistics

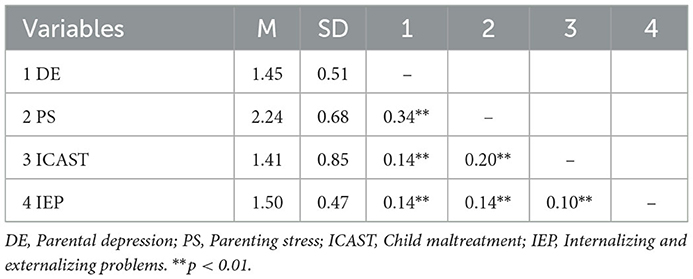

The results of descriptive statistics and correlations between study variables are presented in Table 1. As indicated, parental depression was positively associated with child maltreatment (r = 0.14, p < 0.01), parenting stress (r = 0.34, p < 0.01), and internalizing and externalizing problems in children (r = 0.14, p < 0.01). Parenting stress was positively associated with child maltreatment (r = 0.20, p < 0.01) and internalizing and externalizing problems in children (r = 0.14, p < 0.01).

The relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems

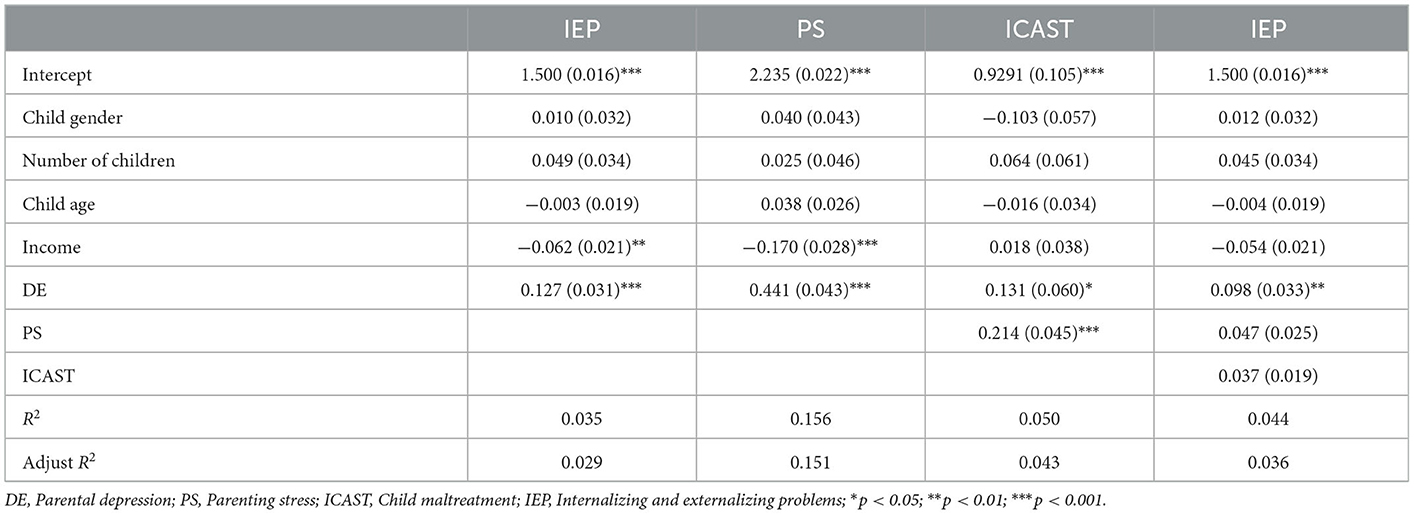

The results of the regression analysis are presented in Table 2. The results showed that parental depression was positively associated with child internalizing and externalizing problems (β = 0.127, S.E.= 0.031, R2 = 0.035, and p < 0.001), with controlling children's genders and ages, the number of children in the family, and family monthly income.

Table 2. The regression between parental depression, parenting stress, child maltreatment, and internalizing and externalizing problems (n = 855).

Mediation analysis

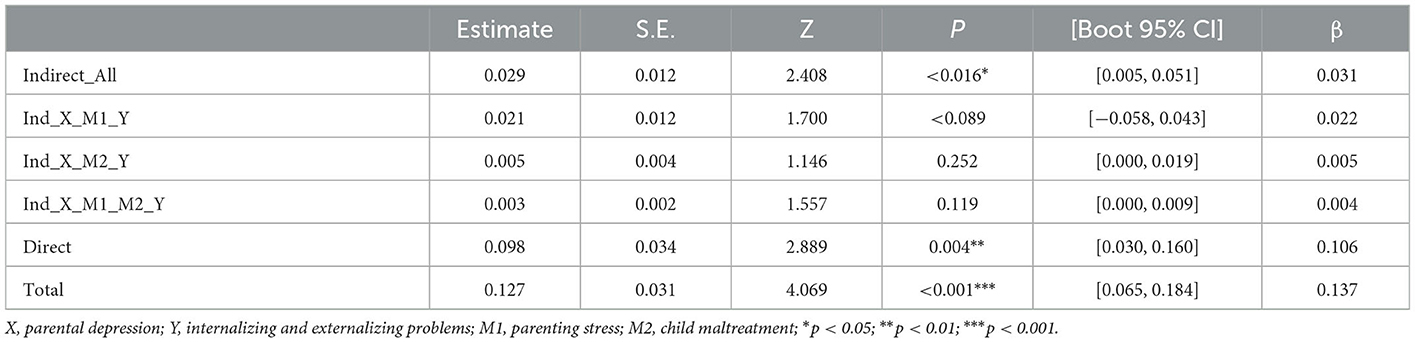

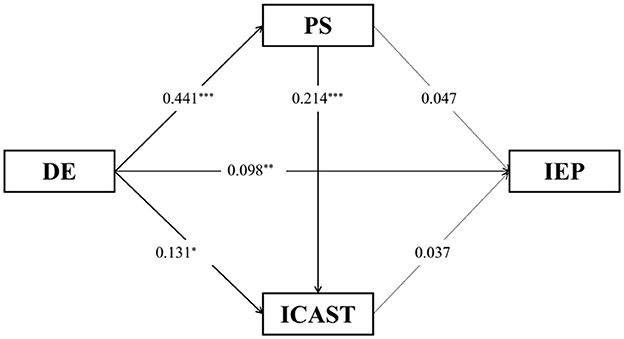

The results of the mediation analysis are presented in Table 3 and Figure 2. The results showed that parental depression was positively associated with parenting stress (β = 0.441, S.E.= 0.043, R2 = 0.156, and p < 0.001) when controlling children's genders and ages, the number of children in the family, and family monthly income. In the model of CES-D-PS-ICAST, parental depression was positively associated with child maltreatment (β = 0.131, S.E.= 0.060, R2 = 0.050, and p < 0.05), and parenting stress was positively associated with child maltreatment (β = 0.241, S.E.= 0.045, R2 = 0.050, and p < 0.001). In the model of CES-D-PS-ICAST-IEP, parental depression was positively associated with child internalizing and externalizing problems (β = 0.098, S.E.= 0.033, and p < 0.01) when controlling children's genders and ages, the number of children in the family, and family monthly income. Moreover, the results of the Bias-corrected percentile method showed that the 95% CI of indirect effects of parenting stress and child maltreatment were [−0.058, 0.043] and [0.000, 0.019], respectively, and the 95% CI of direct effect was [0.030, 0.160], which suggested that child maltreatment mediated the relationships between parental depression and children's internalizing and externalizing problems. Additionally, the results of the Bias-corrected percentile method showed that the 95% CI of all indirect effects of the combination of parenting stress and child maltreatment was [0.000, 0.160], which suggested that parenting stress and child maltreatment mediated the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Additionally, a moderation analysis was also performed, and the results showed that there were no gender effects.

Table 3. The indirect paths between parental depression and internalizing and externalizing problems through parenting stress and child maltreatment (n = 855).

Figure 2. The mediation model between parental depression and children's internalizing and externalizing problems through parenting stress and child maltreatment.

Discussion

The present study explored the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems and examined the roles of parenting stress and child maltreatment in those relationships within the Chinese cultural context. As such, it broadens the scopes of childhood and family studies. These findings suggested that parental depression was positively associated with child internalizing and externalizing problems, and child maltreatment and the combination of parenting stress and child maltreatment mediated the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, respectively.

The results showed that parental depression was positively associated with parenting stress, which was consistent with previous studies (56). Individuals with depression may have less self-efficacy (57), which may contribute to high levels of parenting stress. The results also showed that parental depression was positively associated with child maltreatment, which was consistent with previous studies (58, 59). Similarly, according to the family system theory, depressed parents may impair child development by causing internalizing and externalizing problems in their children. Meanwhile, parenting stress was positively associated with child maltreatment, which was consistent with previous studies (41). These findings suggest that parental depression may be an important factor in child development.

Moreover, the results showed that child maltreatment mediated the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, which indicated that parental depression not only had a direct effect on child internalizing and externalizing problems but also had an indirect effect via child maltreatment. Individuals with high levels of depression may have disorganized interactions with children, and these disorganized interactions may be considered as some kind of child maltreatment, contributing to child internalizing and externalizing problems (60). Depressed parents may reject their children, which may increase child internalizing and externalizing problems (61). These findings suggest that child maltreatment may be one of the bridges between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems.

Additionally, the results showed that parenting stress and child maltreatment progressively mediated the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, which suggested that parental depression influenced child internalizing and externalizing problems via the combination of parenting stress and child maltreatment. Individuals with depression may have low levels of self-efficacy (57) and attention biases in negative information (29), which may contribute to high levels of parenting stress, and these high levels of parenting stress may increase the risk of child maltreatment, which, in turn, contributes to high levels of child internalizing and externalizing problems. The results confirm the assumptions offered by the model of depressed mothers and maladaptation of children and those proposed by the family system theory, and raises the importance of exploring parental depression. These findings suggest that parental depression influences how parents treat their children (e.g., parenting stress and child maltreatment) and that it can lead to child internalizing and externalizing problems.

Some conclusions can be reached with the results of the current study. First, parental mental health is an important issue for children and families, and may increase the risk of parenting stress, child maltreatment, and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Governments and communities should invest in some programs that aim to improve the mental health of parents, and provide some strategies for preserving positive mental health. Second, parenting stress and child maltreatment are two mediators in the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, and decreasing parenting stress and child maltreatment may reduce the influence of parental depression on child internalizing and externalizing problems. Governments and communities should support parents with materials and mental health support through some programs, which may decrease parenting stress. Parents should learn some positive strategies for educating children, which may decrease the risk of child maltreatment.

Some limitations should be acknowledged in the current study. First, the present study contained few male participants who were parents, which may affect the data on parental depression. Future studies should recruit couples for the study, which may give much more solid evidence on parental depression and parenting stress. Second, the current study used cross-sectional designs to examine the pathways between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, which may not verify a causal relationship. Future studies should apply longitudinal designs to examine the mechanisms linking parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Third, the current study used self-report questionnaires to collect the data, which may lead to results that incorporated memory bias and social desirability. Future studies should collect data with different methods (e.g., interviews, questionnaires, and experiments), which may provide much more accurate information.

Conclusion

The present study explored the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, and examined the roles of parenting stress and child maltreatment in those relationships within the Chinese cultural context. In doing so, it broadens the scopes of family studies. The findings suggested that parental depression was positively associated with child internalizing and externalizing problems, and child maltreatment and that the combination of parenting stress and child maltreatment mediated the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems, respectively. Parental depression not only had a direct effect on child internalizing and externalizing problems but also had an indirect effect via parenting stress and child maltreatment. Decreasing the levels of parenting stress and child maltreatment should be applied in interventions to break the relationships between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems in the Chinese cultural context.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Beijing Normal University. The patients/participants provided their online informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CC designed the study, written and revised the manuscript, and completed the data analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China [21YJC880005] and the Department of Education of Guangdong Province [2021GXJK199].

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the families and teachers who participated in the study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.962951/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

PANDA, The project of ability and nurture in dreaming age; RMB, Chinese currency; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; PSI-SF, Parenting Stress Index-Short Form; ICAST-P, ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tools Parent's Version; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; DE, Parental depression; PS, Parenting stress; ICAST, Child maltreatment; IEP, Internalizing and externalizing problems.

References

1. Winsler A, Diaz RM, Atencio DJ, McCarthy EM, Adams Chabay L. Verbal self-regulation over time in preschool children at-risk for attention and behavior problems. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discipl. (2000) 41:875–86. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00675

2. Bulotsky-Shearer RJ, Domínguez X, Bell ER, Rouse HL, Fantuzzo JW. Relations between behavior problems in classroom social and learning situations and peer social competence in Head Start and Kindergarten. J Emot Behav Disord. (2010) 18:195–210. doi: 10.1177/1063426609351172

3. Rademacher A, Zumbach J, Koglin U. Cross-lagged effects of self-regulation skills and behavior problems in the transition from preschool to elementary school. Early Child Dev Care. (2022) 192:631–4. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2020.1784891

4. Guo R, Mao D, Li J, Luo X, Jiang Y, Liu J. Investigation on the behavior problems of children aged 3 to 5 years in Chang Sha and comparison of the norm of Conners Parent Symptom Questionnaire in Chinese and American urban children. Chin J Contemp Pediatr. (2011) 13:900–3.

5. Mazza JR, Pingault JB, Booij L, Boivin M, Tremblay R, Lambert J, et al. Poverty and behavior problems during early childhood: the mediating role of maternal depression symptoms and parenting. Int J Behav Dev. (2017) 41:670–680. doi: 10.1177/0165025416657615

6. Alto ME, Warmingham JM, Handley ED, Rogosch F, Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Developmental pathways from maternal history of childhood maltreatment and maternal depression to toddler attachment and early childhood behavioral outcomes. Attachment Hum Dev. (2021) 23:328–49. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2020.1734642

7. Kaiser RH, Snyder HR, Goer F, Clegg R, Ironside M, Pizzagalli DA. Attention bias in rumination and depression: cognitive mechanisms and brain network. Clin Psychol Sci. (2018) 6:765–82. doi: 10.1177/2167702618797935

8. Yoon AS, Zhai F, Gao Q, Solomon P. Parenting stress and risks of child maltreatment among Asian immigrant parents: does social support moderate the effects? Asian Am J Psychol. (2021). doi: 10.1037/aap0000251

9. Song Z, Wang F, Wang M. The relationship between paternal or maternal physical discipline and preschoolers' externalized problem behaviors: the mediating effect of children's effortful control. Chin J Special Educ. (2018) 221:45–51.

10. Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol Rev. (1999) 106:458–90. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458

11. Kerr M, Bowen M. Family Evaluation: The Role of the Family as an Emotional Unit That Governs Individual Behavior and Development. Penguin Books (1988).

12. Ma X, Chen F, Xuan X, Wang Y, Li Y. The effect of maternal depression on preschoolers' problem behaviors: mediating effects of maternal and paternal parenting stress. Psychol Dev Educ. (2019) 35:103–11. doi: 10.16187/j.cnkiissn1001-4918.2019.01.12

13. Zong L, Liu J, Li D, Chen X. Effects of maternal depression on infants' internalizing behavior problems: a moderated mediation model. J Psycholog Sci. (2014) 37:1117–24.

14. Marçal. Pathways to adolescent emotional and behavioral problems: an examination of maternal depression and harsh parenting. Child Abuse Neglect. (2021) 113:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104917

15. Chen F, Yuan C, Zhang C, Li Y, Wang Y. Material depression, parental conflict and infant's problem behavior: moderated mediating effect. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2015) 23:1049–52. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki1005-3611.2015.06.021

16. Hentges RF, Graham SA, Plamondon A, Tough S, Madigan S. Bidirectional associations between maternal depression, hostile parenting, and early child emotional problems: findings from the all our families cohort. J Affect Disord. (2021) 287:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.056

17. Kallapiran K, Jayanthini V. Emotional problems in children of mothers who had depression: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Psychol Med. (2021) 43:410–5. doi: 10.1177/0253717621991210

18. Huizink AC, Menting B, De Moor MHM, Verhage ML, Kunseler FC, Schuengel C, et al. From prenatal anxiety to parenting stress: a longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2017) 20:663–72. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0746-5

19. Liang S, Yu T, Liu W, Cheng W. Relationship between postpartum depression and parenting sense of competence of parents: a moderated mediating effect. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2021) 29:1040–4. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.05.030

20. Galbally M, Watson SJ, Boyce P, Lewis AJ. The role of trauma and partner support in perinatal depression and parenting stress: an Australian pregnancy cohort study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2019) 65:225–34. doi: 10.1177/0020764019838307

21. Salloum A, Stover CS, Swaidan VR, Storch EA. Parent and child PTSD and parent depression in relation to parenting stress among trauma-exposed children. J Child Fam Stud. (2015) 24:1203–12. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-9928-1

22. Biondic D, Wiener J, Martinussen R. Parental psychopathology and parenting stress in parents of adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Fam Stud. (2019) 28:2107–19. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01430-8

23. Liu Y, Deng H, Zhang M, Zhang G, Lu Z. The effect of 5-HTTPR polymorphism and early parenting stress on preschoolers' behavioral problems. Psychol Dev Educ. (2019) 35:85–94. doi: 10.16187/j.cnkiissn1001-4918.2019.01.10

24. Liu Y, Deng H, Zhang G, Liang Z, Lu Z. Association between parenting stress and child behavioral problems: the mediation effect of parenting styles. Psychol Dev Educ. (2015) 31:319–26. doi: 10.16187/jcnki.issn1001-4918.2015.03.09

25. Li X, Xie J, Song Y. Grandparents-parents co-parenting and its relationship with maternal parenting stress and children's behavioral problems. Chin J Special Educ. (2016) 4:71–8.

26. Han JW, Lee H. Effects of parenting stress and controlling parenting attitudes on problem behaviors of preschool children: latent growth model analysis. J Korean Acad Nurs. (2018) 48:109–21. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2018.48.1.109

27. Kochanova K, Pittman LD, McNeela L. Parenting stress and child externalizing and internalizing problems among low-income families: exploring transactional associations. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2022) 53:76–88. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01115-0

28. de Maat DA, Jansen PW, Prinzie P, Keizer R, Franken IHA, Lucassen N. Examining longitudinal relations between mothers' and fathers' parenting stress, parenting behaviors, and adolescents' behavior problems. J Child Fam Stud. (2021) 30:771–83. doi: 10.1007/s10826-020-01885-0

29. Beevers CG, Clasen PC, Enock PM, Schnyer DM. Attention bias modification for major depressive disorder: effects on attention bias, resting state connectivity, and symptom change. J Abnorm Psychol. (2015) 124:463–75. doi: 10.1037/abn0000049

30. de Montigny F, Gervais C, Pierce T, Lavigne G. Perceived paternal involvement, relationship satisfaction, mothers' mental health and parenting stress: a multi-sample path analysis. Paternal Involv Maternal Wellbeing. (2020) 11:578682. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.578682

31. Xuan X, Chen F, Yuan C, Zhang X, Luo Y, Xue, Y.e., et al. The relationship between parental conflict and preschool children's behavior problems: a moderated mediation model of parenting stress and child emotionality. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2018) 95:209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.10.021

32. Holmes MR. Aggressive behavior of children exposed to intimate partner violence: an examination of maternal mental health, maternal warmth and child maltreatment. Child Abuse Neglect. (2013) 37:520–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.12.006

33. David VB. Associations between parental mental health and child maltreatment: the importance of family characteristics. Soc Sci. (2021) 10:1–13. doi: 10.3390/socsci10060190

34. Mustillo SA, Dorsey S, Conover K, Burn BJ. Parental depression and child outcomes: the mediating effects of abuse and neglect. J Marriage Family. (2011) 73:164–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00796.x

35. Plant DT, Barker ED, Waters CS, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Intergenerational transmission of maltreatment and psychopathology: the role of antenatal depression. Psychol Med. (2013) 43:519–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001298

36. Isumi A, Doi S, Ochi M, Kato T, Fujiwara T. Child maltreatment and mental health in middle childhood: a longitudinal study in Japan. Am J Epidemiol. (2021) 191:655–64. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab275

37. Watters ER, Wojciak AS. Childhood abuse and internalizing symptoms: exploring mediating and moderating role of attachment, competency, and self-regulation. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 117:105305. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105305

38. Ma J, Han Y, Kang HR. Physical punishment, physical abuse, and child behavior problems in South Korea. Child Abuse Neglect. (2022) 123:105385. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105385

39. Godinet MT, Li F, Berg T. Early childhood maltreatment and trajectories of behavioral problems: exploring gender and racial differences. Child Abuse Neglect. (2014) 38:544–56. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.018

40. Taylor CA, Guterman NB, Lee SJ, Rathouz PJ. Intimate partner violence, maternal Stress, nativity, and risk for maternal maltreatment of young children. Am J Public Health. (2009) 99:175–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126722

41. Crouch E, Radcliff E, Brown M, Hung P. Exploring the association between parenting stress and a child's exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Child Youth Serv Rev. (2019) 102:186–92. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.05.019

42. Maguire-Jack K, Negash T. Parenting stress and child maltreatment: the buffering effect of neighborhood social service availability and accessibility. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2016) 60:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.11.016

43. Qiao D, Xie Q. Public perceptions of child physical abuse in Beijing. Child Family Soc Work. (2017) 22:213–25. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12221

44. Radloff L S. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. (1977) 1:38577Psychol Meas1177/014662167700100306

45. Wang X, Wang X, Ma H. The Chinese version of center for epidemiological studies depression scale. J Chin Mental Health. (1999) 1:178.

46. Lin Y, Zhang Q, Qian M, Zhu C. College students' depression and rejection sensitivity: the mediating role of social avoidance and distress. China J Health Psychol. (2022) 30:1371–5. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2022.09.018

47. Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index/Short Form manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources (1995).

48. Wang W, Wang S, Cheng H, Wang Y, Li Y. The mediation effect of fathers' parental burnout in parenting stresses and teenagers' mental health. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2021) 29:858–62. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.04.040

49. Runyan DK, Dunne MP, Zolotor AJ, Madrid B, Jain D, Gerbaka B. The development and piloting of the ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tool-Parent version (ICAST-P). Child Abuse Neglect. (2009) 33:826–32. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.006

50. Meinck F Murray AL Dunne MP Schmidt P Nikolaidis G the BECAN Consortium. Factor structure and internal consistency of the ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tool Parent Version (ICAST-P) in a cross-country pooled data set in nine Balkan countries. Child Abuse Neglect. (2021) 115:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105007

51. Chen C, Wang X, Huang Z, Fu X, Qin J. Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tools Parent's Version (ICAST-P). Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 109:104715. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104715

52. Goodman. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (1997) 38:581–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

53. Huang H, Wang X, Lv B. Family cumulative risk and problem behavior of migrant preschool children: a moderated mediation model. Stud Psychol Behav. (2021) 19:779–85.

54. Xu W, Wang M, Deng J, Liu H, Zeng H, Yang W. Reliability generalization for the Chinese version of strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2019) 27:67–72. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2019.01.014

55. Wen Z, Hou J, Chang L. A comparison of moderator and mediator and their applications. Acta Psychol Sin. (2005) 37:268–74.

56. Babore A, Trumello C, Lombardi L, Candelori C, Chirumbolo A, Cattelino E, et al. Mothers' and children's mental health during the covid-19 pandemic lockdown: the mediating role of parenting stress. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2021). 54:134–46. doi: 10.1007/s10578-021-01230-6

57. Bentley G, Zamir O. The role of maternal self-efficacy in the link between childhood maltreatment and maternal stress during transition to motherhood. J Interpers Violence. (2021) 37:19576–98. doi: 10.1177/08862605211042871

58. Li T, Gu J, Xu H. The relationship between paternal depression and children's problem behavior: the chain mediating roles of paternal parenting self-efficacy and paternal parenting style. Stud Psychol Behav. (2021) 19:66–73.

59. Venta A, Velez L, Lau J. The role of parental depressive symptoms in predicting dysfunctional discipline among parents at high-risk for child maltreatment. J Child Fam Stud. (2016) 25:3076–82. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0473-y

60. Liu L, Li Y. The detriment of mother's depression and punishment on preschooler's problem behaviors and the protecting father. Psychol Dev Educ. (2013) 29:533–40. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2013.05.009

Keywords: parental depression, child behavior problems, parenting stress, child maltreatment, Chinese samples

Citation: Chen C (2023) The relationship between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems: The roles of parenting stress and child maltreatment. Front. Public Health 11:962951. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.962951

Received: 07 June 2022; Accepted: 17 January 2023;

Published: 07 February 2023.

Edited by:

Xiaoqin Zhu, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Karen Martinez-Gonzalez, University of Puerto Rico, Puerto RicoSon H. Nghiem, Griffith University, Australia

Copyright © 2023 Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chen Chen,  chenchen2020@bnu.edu.cn

chenchen2020@bnu.edu.cn

†ORCID: Chen Chen orcid.org/0000-0002-0346-6063

Chen Chen

Chen Chen