Did manga shape how the world sees Japan?

Z-Link

Z-Link

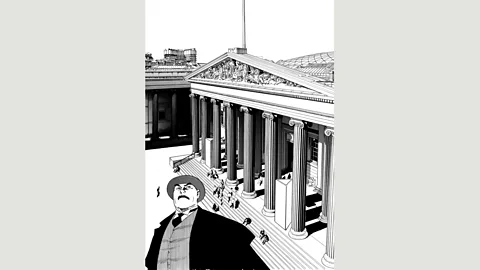

As the largest exhibition of manga outside of Japan opens at London’s British Museum, Christine Ro looks at how the visual narrative artform influenced the globe.

As manga enthusiasts like to say, there’s a manga for everyone. Whether you want to read about teenage athletes, serial killers, anthropomorphic cats, nuclear clean-up workers, powerful librarians, or homeless deities, you’ll find a work of manga about them. And London’s British Museum is currently exploring that variety in the largest exhibition of manga ever to take place outside of Japan, looking at the visual narrative artform’s global appeal and cultural crossover, and showcasing its influence around the world.

Manga and anime (Japanese animation) offer the first formative exposure to the culture for many non-Japanese people around the world. This is true of Korean cartoonist Yeon-sik Hong, who documented his family’s attempts to achieve work-life balance in the graphic memoir Uncomfortably Happily. Hong says: “When I think of the Japanese culture, the first things that come to my mind are manga and animation. Many Koreans who don’t have any knowledge about comics and animations will think in the same way. I think those two represent Japanese culture.”

Yeon-sik Hong, Drawn & Quarterly

Yeon-sik Hong, Drawn & Quarterly

This is a positive association, Hong believes, even though Korean-Japanese relations are complex. After all, “most Koreans still remember well Japanese invasion of the country and its colonial rule. So we call Japan a country that is so close, yet so far.” The closeness includes geographical proximity, as well as an understanding fostered by pop culture.

Of course there has been some resistance on both sides. Korean comics in Japan tend to be localised, or scrubbed of Korean design and language elements, for the sake of a Japanese audience accustomed to reading homegrown content. Notoriously, the 2005 Japanese Manga Kenkanryu (“Hating the Korean Wave”) expressed a minority view in Japan of Korean cultural inferiority. Manga Kenkanryu was followed by similar books in Korea, taking aim at Japanese culture. The tension was prompted in part by a growing rivalry in pop culture exported around the world, including Japanese manga and Korean manhwa.

Colonial legacies also affect the reception of manga far from Asia. Alexandra Gueydan-Turek, an associate professor of French and Francophone studies at Swarthmore College in the US, sees manga as a useful way for postcolonial nations to grapple with their own cultural identities. She’s traced the birth of Dz-manga, or Algerian manga, to dual trends: “a foreignisation which claims manga as an alternative to both Western graphic forms and traditional Islamic art; and a localisation through narratives that primarily address the young local readers”.

So Japan is distant enough, in both shared history and geography, to present an alternative to traditional French dominance in Algeria (where, as in other Arabic-speaking nations, the football-themed Captain Tsubasahas been a hit). Gueydan-Turek sees this as a positive opening up of cultural possibilities, which isn’t necessarily about Japan itself. “Dz-manga’s appeal is less about an attraction to Japanese culture and more about manga as an adaptable global popular cultural product.”

Z-Link

Z-Link

For Algerians, “manga is a way for them to discover a culture which is far from Algerian”, agrees Salim Brahimi, director of the Algerian manga publisher Z-Link. “The big way for Algerians to discover and live the Japanese culture is manga”, although other Japanese cultural forms, like video games and food, have also crossed over. Z-Link publishes titles in Arabic, French and Berber, as well as the magazine Laabstore, dedicated to manga, anime and games.

Chip off the woodblock

To some extent, the more recent Algerian interest in manga does mirror the longstanding French fascination with Japanese culture. From the late 17th Century, French collectors snapped up Japanese goods misleadingly categorised as ‘chinoiseries’, such as lacquered cabinets. This later extended to ukiyo-e, or woodblock prints, whose exports helped propel the Japonisme craze in Europe. These woodblock prints were also early precursors of modern-day manga.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British Museum

In modern-day France, a long-term interest in Japan has mingled with the strong culture of bande dessinée, or French and Belgian comics. “The current popularity of manga [there] is generally traced to the proliferation of anime on French TV in the mid-1970s and 1980s,” according to Gueydan-Turek. This was largely limited to blockbuster manga and encouraged “a simplified and distorted view of Japanese culture”, where aspects like kawaii (the culture of cuteness) and certain violent aesthetics prevailed “over the artistic and literary nuance of more multilayered graphic works such as Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen”. One manga series beloved in France has been the cat-centric Chi’s Sweet Home. However, Gueydan-Turek points to the la nouvelle manga movement as a less mainstream alternative, which brings together Japanese mangaka (manga authors) and Franco-Belgian bande dessinée artists in a hybridised approach to the multiple cultures.

Konami Kanata, Kodansha Ltd

Konami Kanata, Kodansha Ltd

If manga has acted as a vehicle for continued international links in France, and as an alternative to the French cultural presence in Algeria, it’s provided a counter to perceived American values in Russia, where Sailor Moon has become hugely popular. Manga spread in the post-Soviet era, allowing certain educated youth to seek refuge from both the constraints of communism and the money-seeking excesses of capitalism. It was a key part of the geeky new otaku subculture (Japanese men who love manga, anime and computers) that provided a ‘protective niche’ for Russian young people.

More generally, manga’s impact on readers and their worldview has been magnified by the fact that most are young and impressionable when they first encounter it. A survey conducted in 2006-7 in four European countries found that 15% of respondents started reading manga before the age of 10, 45% between 10 and 14, and 29% while secondary school-aged. This is a crucial time for identity formation – whether manga helps shape perceptions of other countries, or gives young people a gateway to Japanese culture, as has been documented among British teenagers.

For decades now, Susan Napier has been tracking these kinds of attitudes towards manga. Napier teaches Japanese studies at Tufts University in the US, and last year published a book about animator Hiyao Miyazaki. For the first generation of American students whose initial exposure to Japanese culture came through manga and anime, their images were often of samurai and schoolgirls. She worries about the latter impression, especially, which perpetuates infantilising stereotypes of Asian female docility, without representing the vast breadth of characters who appear in manga.

A gender agenda

As in life, sex in manga can be complicated. The harem genre, which typically features multiple adoring women orbiting around a man, appears to be a form of wish fulfilment that might be spreading misleading ideas internationally of Asian women’s sexual availability. That’s not to mention certain hentai manga, like the tentacle-based pornographic manga that Napier sees as a gendered “dream of power”.

Yet ever since its inception, manga has given more space to playfulness around gender and sexuality than many other media. Pioneering mangaka Tezuka Osamu created characters with fluid genders in Metropolis and Princess Knight. (He also created the manga convention of big-eyed, overtly cute characters based on the postwar influence of American creations like Betty Boop and Disney characters.)

Akiko Higashimura Kodansha Ltd

Akiko Higashimura Kodansha Ltd

As well, the yaoi, or boys’ love, sub-genre has given primarily heterosexual women a venue for exploring their own sexuality through depictions of male-male relationships. In a way, Napier says, “manga and anime have held up very progressive models”, despite discomfort with homosexuality in the larger Japanese culture, and despite some Western stereotyping of Japanese sexual attitudes. Some of the queer cosplayers Napier has interviewed have suggested that yaoi offers a liberating alternative to American popular culture.

So to Napier, “the world of anime and manga is both a Japanese world and it’s another world of fantasy. It plays on both registers as a genuine culture ― which exists, and they can go to Japan ― and also this other culture which they can make up in their mind’s eye, which I think is very typical of someone like Van Gogh.” Manga’s cultural malleability is one reason it has crossed borders in so many forms.

“Manga now is becoming an international language,” affirms Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, a curator of Japanese art at the British Museum and a professor of Japanese art and culture at the University of East Anglia. Rousmaniere co-curated the British Museum’s Manga exhibition, and draws a link to the explosive popularity and internationalisation of sushi within a generation, where what you see at chain restaurants in the West isn’t necessarily like the sushi at restaurants in Japan. (The California roll is neither Japanese nor American, but more of a Canadian invention.)

Yukinobu Hoshino, Shogakukan Inc

Yukinobu Hoshino, Shogakukan Inc

So the internationalisation of manga looks likely to only expand in the future, as an art form that’s both intensely Japanese and infinitely adaptable around the world.

Manga is at the British Museum until 26 August 2019.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.