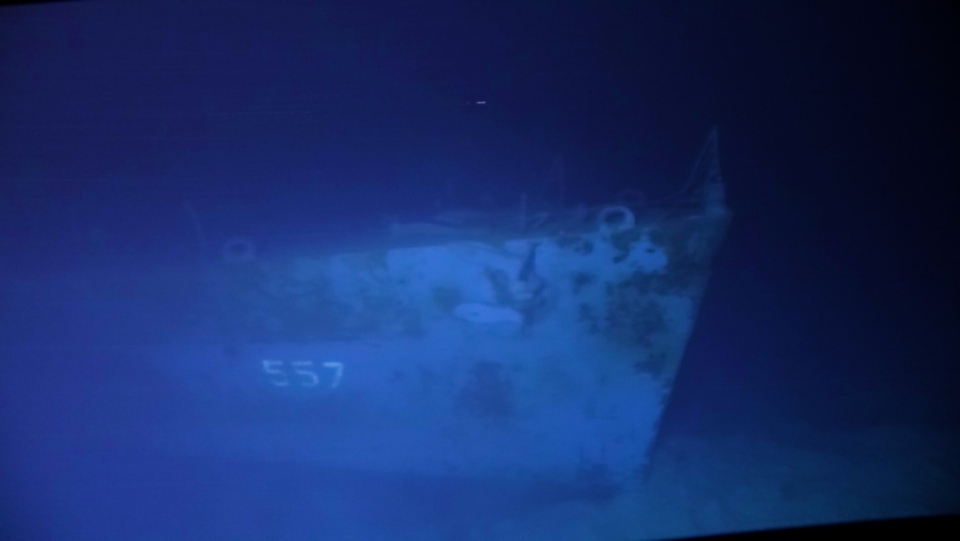

TORONTO -- A privately-funded expedition piloted by two former U.S. Navy officers and organized by EYOS Expeditions has successfully re-located, surveyed and filmed the world’s deepest known shipwreck.

The USS Johnston lies at a depth of 21,180 feet or 6,456 metres in the Philippine Sea. To put it in context, the Johnston is in water 62 per cent deeper than the Titanic’s wreck in the North Atlantic.

The Johnston was a U.S. Navy Fletcher-class destroyer that sank on October 25, 1944, in an intense battle with Japanese forces off the coast of Samar Island during the Battle of Leyte Gulf – thought to be the largest naval battle in history, according to a press release.

The shipwreck was originally discovered in 2019, and while that expedition was able to film pieces of the vessel by a remotely-operated vehicle (ROV), the majority of the wreck lay too deep for the ROV to reach.

In March, Ret. U.S. Navy Commander and funder of the expedition Victor Vescovo, and Ret. U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commander Parks Stephenson, assisted by Shane Eigler, a senior submarine technician from Triton Submarines, logged two separate, eight-hour dives to the wreck of the Johnston. This marks the deepest wreck dives, manned or unmanned, in history, the release states.

No human remains or clothing were seen at any point during the dives and nothing was taken from the wreck.

“We used data from both the U.S. and the Japanese accounts and as is so often the case the research brings the history back to life,” Stephenson said in the release. “Reading the accounts of the Johnston’s last day are humbling and need to be preserved as upholding the highest traditions of the Navy. This was mortal combat against incredible odds.”

Vescovo and his crew will not be releasing the sonar data, imagery or field notes collected by the expedition to the public, but will be giving them to the U.S. Navy for “dissemination as it deems appropriate.” This comes after “discussions” with the Navy Heritage and History Command in efforts to respect the wreck as the final resting place for many of its crew, the release states.

“We have a strict ‘look, don't touch’ policy but we collect a lot of material that is very useful to historians and naval archivists. I believe it is important work, which is why I fund it privately and we deliver the material to the Navy pro-bono,” Vescovo said.

The USS Johnston was commanded by Ernest E. Evans, a Native American man of Creek and Cherokee heritage from Oklahoma. Evans and his crew chose to stay and face the superior Japanese naval forces to protect other U.S. ships in the area at great cost.

“Commander Ernest Evans and his entire crew went above and beyond the call of duty engaging an overwhelming and vastly superior Japanese force to buy time for the escort carriers he was charged with protecting, to escape,” Rear Admiral Samuel Cox, Director of Naval History and Curator for the Navy, said in the release. “The Johnston was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation -- the highest award that can be given to a ship. Evans was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor, the first Native American in the U.S. Navy and the only destroyer skipper in World War II to be so honored.”

Three other ships lost in the Battle of Leyte Gulf have yet to be found.