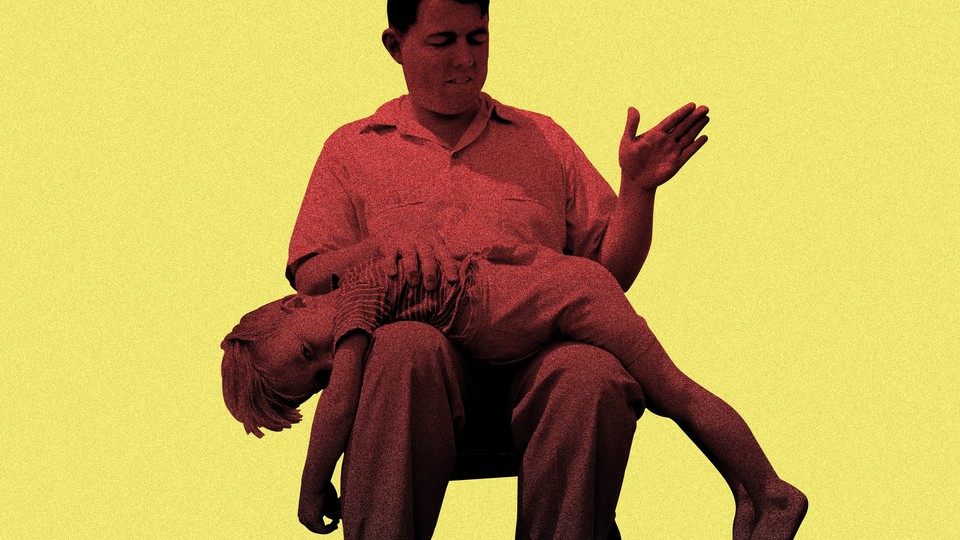

How Spanking Affects Later Relationships

There is clear evidence that it’s best to show children relationship skills that never escalate to physical harm.

Spanking looks to be instantly effective. If a child is misbehaving—if he keeps swearing, or playing with matches—and then you spank that child, the behavior stops immediately.

The effect is so apparently obvious that it can drive a sort of delusion. Lived experience tends to be more powerful than facts. One of the few memories that many people retain from early childhood is times they were spanked. The desire to believe it was “for our own good” is strong, if only because the alternative interpretation is bleak.

It’s in the face of personal experiences like these that science has been flailing for generations. Some 81 percent of Americans believe spanking is appropriate, even though decades of research have shown it to be both ineffective and harmful. The refrain I keep hearing is, “Well, I got spanked, and I turned out okay.”

To which a person might reply, “Did you?”

For years, the American Academy of Pediatrics has been warning against spanking, and many countries have laws against it. A 2007 UN convention has said corporal punishment violates the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which protects children from “all forms of physical or mental violence,” and should be banned in all contexts. Psychologist Alan Kazdin, the director of the Yale Parenting Center and former president of the American Psychological Association, has admonished that spanking is “a horrible thing that does not work.” It predicts later academic and health problems: Adults who were spanked as children “regularly die at a younger age of cancer, heart disease, and respiratory illnesses.”

If the fear of robbing one’s child of years of life were not enough, this month two more studies added to the pile finding that childhood spanking has negative effects on the people we later become. In the extremely depressing journal Child Abuse and Neglect, researcher Julie Ma and colleagues found that spanking was associated with later aggressive behavior. Ma has previously linked spanking to later antisocial behavior, anxiety, and depression. Then last week The Journal of Pediatrics reported that researchers at the University of Texas found a correlation between corporal punishment as a child and dating violence as an adult.

That one struck a chord in light of the national conversation about sexual harassment. Of course, no single act or momentary experience turns a person from a blank slate into a violent or coercive adult. To suggest that childhood experiences explain sexual violence ignores the structural power dynamics that condone and perpetuate it. Still it’s also clear that a person’s understanding of the role of violence in conflict resolution goes way, way back.

“We struggle in this field trying to identify predictors of violence,” said the University of Texas researcher Jeff Temple, who focuses on interpersonal relationships and dating violence among teenagers. “We know that child abuse is related to later dating violence, as is witnessing violence between parents or in the community,” he told me.

That’s why Temple’s team wanted to go back further and see if corporal punishment in itself was associated with dating violence, and it was—even controlling for “child abuse” in a more traditional sense.

(The words I choose to use here are loaded, I know. “Spanking” is minimizing and normalizing of hitting a child. “Child abuse” is overdramatic and it lumps the practice in with the most vicious, high-level malice. “Corporal punishment,” as it’s known internationally, can feel too academic.)

Many researchers tend to see corporal punishment and physical abuse as part of a continuum. Administered too severely or too frequently, corporal punishment is abuse. The notion of a continuum is corroborated by the stated intent of abusers. As much as two-thirds of abuse begins as an attempts to change children’s behavior, to “teach them a lesson.”

Temple’s team at Texas isn’t the first to link spanking and later relationship violence, but it is the first to control for other forms of child abuse. He was influenced by one of the pivotal works in spank-theory discourse, a 2002 meta-analysis by Elizabeth Thompson Gershoff (who is now also at the University of Texas, a geographically unlikely hotbed of resistance to corporal punishment). Gershoff went on to write definitively in 2013, “Spanking and Child Development: We Know Enough Now to Stop Hitting Our Children.”

Temple is less direct: “The point of us doing this research isn’t to tell parents what to do,” he said, conjuring a libertarian-friendly approach to science. “Parenting is difficult and stressful, and people don't like to be told how to do it. Our job is just to provide them the evidence of what works, and what happens long-term.”

This abdication of the moral high ground is principled. He is fundamentally opposed to telling people what not to do. It’s not just a Texas thing; it’s proven not to work. He is instead a champion of “positive disciplining,” meaning focusing on what is good about a particular situation.

“Spanking is punishment, and punishment doesn’t work,” he said. “We know it with rats, we know it with humans. But if you can connect with a kid when they’re doing something right, they’re more likely to do that again in the future.”

As a father himself, he knows this is difficult to adhere to, but he believes this can happen even in the most difficult situation. “If a kid is having a temper tantrum and throwing things, and then next time they have a tantrum but don’t throw anything, say ‘I’m really glad you didn't throw anything.’”

The other evidence-based approach he recommends is taking something positive away. For younger children, that can mean taking away a toy temporarily. For older children and teenagers, this can mean taking away a cell phone. All of this is in service of teaching children to be respectful without disrupting the vital positive elements of the caretaker-child relationship.

At a larger scale, Temple believes one promising approach is school-based teaching of relationship skills. He is involved with a program call the Fourth R (meaning relationships), which is dedicated to baking healthy adolescent relationships into the curriculum. The ultimate target is violence of multiple sorts, including bullying, dating violence, peer violence, and group violence. But the focus is positive, not punitive, on how to build healthy relationships.

Temple believes this work is relevant to the national conversation on sexual assault and harassment. The discourse is doing an extraordinary job punishing—and of telling people how not to behave. Publicly accused perpetrators of sexual violence have been removed from their positions in droves, with the notable exceptions of Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore and President Donald Trump. At the same time, though, if there is evidence that punishment-based approaches are ineffective in children—and the behavior of these men is in many ways juvenile, egocentric, inhumane—then this punitive approach is at best incomplete. It carries with it the risk of a false sense of progress.

When the public perceives that we have cleansed the halls of Congress and corporations of the several bad eggs who commit sexual harassment (violent or otherwise), how much of the structural problem is really solved? In the interim before the total eradication of men, what keeps these positions from being filled again by bad eggs? The punitive phase will, it seems, need to go hand in hand with positive reinforcement. This seems absurd in an ostensibly civilized era: No one deserves a reward for being a basically reasonable respectful human. Or maybe they do.

There is no dispute that early exposures are critical to later social habits. Relationships with adults at a very young age shape how we learn to relate. The degree to which violence and perceived respect enter into that relationship are important.

“If we can teach kids healthy relationship skills, maybe it attenuates some of the effects of corporal punishment,” said Temple. “And then, with things like sexual assault and harassment, definitely that happens less when we teach healthy relationship skills—be it peer, colleague, romantic. That means teaching healthy relationships to everyone, but especially boys. I think that might be where the key is.”