As told to T. Cole Rachel, 3005 words.

Tags: Film, Process, Production, Success, Inspiration.

On the detective work of making documentary films

Filmmaker Frédéric Tcheng on viewing fashion through a documentary lens, creating a film about the designer Halston, and moving into narrative filmmaking.You’ve made several big-name fashion documentaries. How do you typically land on a subject?

For Halston it started with the producer, Roland Ballester, coming to me. He had a contact with the Halston family and Lesley Frowick, who is in the film, and he was looking for a director. My first reaction was, “I don’t want to do another fashion documentary, thank you very much.” I didn’t know much about Halston, unfortunately. I knew he was on the periphery on other projects I had worked on, like Diana Vreeland, but the main impression I had is that he was the flamboyant, Studio 54 designer who was partying all the time. That’s part of the story, but just the tip of the iceberg. And when I discovered the rest of the iceberg, that’s when I got hooked.

What I think particularly attracted me was the business story, the showdown between the corporations and Halston in 1983 and him being ousted from his own company. It resonated with me personally because I’ve had experiences with corporations that were tricky and that made me feel really alone, when things were all about the bottom line. So I wanted to speak about that, to talk about the creative and the business aspects that are essential in our profession and how you negotiate that as an artist. I was devastated when I learned about the story of his business, and that’s when I decided to take it on.

I started to think about how I was going to make it interesting. You’re going to be entering this person’s world for a long time, so you want to know there’s something there that will maintain your interest level. I didn’t want it to be just a another documentary for me. Early on I became interested in the idea of doing a hybrid documentary where part of it would be scripted, which made sense since Halston’s story actually felt very scripted. He scripted it himself. He invented a new persona at each stage of his career. It’s as if he would erase the past in order to move forward. So, the scripted element became a big part of why I wanted to take this on.

With most documentaries, particularly fashion documentaries, often it’s that same formula of archival footage, talking head, archival footage, talking head. So having the narrative element in Halston, in which Tavi Gevinson plays this fictional character, makes it interesting. How hard was it to figure out how that would work or what purpose that narrator character would serve?

It was very hard. It took many, many attempts, many different versions of the script, and even in the editing it changed significantly. I had to deal with how to balance the documentary elements and the fictional parts. I think we realized, as we went on, that the fictional parts needed to be in support of the documentary, and they couldn’t take over the film. We realized what people really wanted to see was Halston. It’s very hard to compete with the real Halston.

So it was a fine game of balancing how much and when she would come in. One of the big references for the scripted elements, and for the film in general, was Citizen Kane. Halston is like Kane. There is this incredible rise-and-fall story there, as well as a mystery about where this guy came from and who he really is. Why is he always hiding behind dark sunglasses?

Halston and longtime muse, Liza Minnelli ©Berry Berenson Perkins

Halston and longtime muse, Liza Minnelli ©Berry Berenson Perkins

You’ve made several documentaries now and so much of how or why something succeeds depends on access—access to the person if they are still living, access to archives. Part of the joy in watching is seeing all of this footage that no one may have ever seen before. How does that part of the process work? It must be like being a detective.

Well, in the case of Halston, his niece had a lot of footage. His niece, who is in the film, has copies of his private tapes that were thought to have all been erased, 215 of them. But more importantly, she gave us access to his inner circle. Once she interviewed with us and felt confident that we were not going to portray Halston in a biased way, she opened the door to the inner circle. All of the models would not have talked to us if Lesley had not talked first. And that goes all the way to Liza Minnelli. It’s a very tight-knit group. We see aspects of that in the film, but there’s almost a cultish aspect to Halston’s persona, and the way he built his entourage. To this day people are still super protective of that.

When you are drowning in archival material and there are all of these people who have often differing opinions about the subject, how hard is it to remain objective? Halston, for example, is very even-handed in this respect. You don’t shy away from how difficult he could be, but it also speaks to his character that all of these people are still so protective of his legacy.

I think he was like a guru. He was this incredibly seductive, magnetic person. Even from his earliest days at Bergdorf, people say that he had this capacity to hypnotize. He was charming. He was personal, but not too personal. He was just so socially fluid.

I do feel like the thrill of making the film was doing this detective work and investigation. I went so far beyond the initial vision that I had at the beginning. The Halston everyone remembers is the Halston from Studio 54 with the dark sunglasses and the white blazer. But what really fascinated me was going back to the early days and seeing how he started, and how underground and counterculture he actually was in the beginning. At his first salon, after he leaves Bergdorf, he has long, shaggy hair and the giant belt and everything. He was having poetry readings at his fashion house. That was what they would do on the weekends. It’s like a totally different Halston. It’s not the grand, sort of aloof Halston of later, it’s someone who is highly connected to the culture who is employing black models at a time where it’s not done. He’s employing someone like Pat Ast, just because he thinks she’s super fun. The young, free-spirited Halston eventually became this Xanadu-trapped Halston.

Making these kinds of documentaries involves so many different kinds of work. Not only do you have to do the detective work of finding lost or unseen materials, you also have to secure rights to things and then spend time chasing down all of these people and convincing them to talk to you on camera. That part of it—both convincing them to talk and then interviewing them—would seem to require its own special skill set. You also often only have a very limited window of time with people, during which you need them to spill their guts. How is that part of the process for you?

I tend to make people cry. I tend to really make women cry in the interviews. I don’t know why, but I make people emotional. That’s one of my skills, I’ve learned. I don’t know where I got that from. I think from the outside, I can be sort of reserved, or whatever. I appear that way. I’m not necessarily the person at the party that you’re gonna reveal yourself to, but at the same time, I have always really loved hearing people’s intimate stories. That’s really the core of why I make documentaries. I’m interested in people. I’m interested in their story. You also just have to be honest with people, because in an interview people can almost always immediately tell what it is you’re after. So yes, interviewing is sort of a people skill, but it’s really about more than that. It’s about where your heart actually is.

People can sense if you have an agenda.

Yeah, and if they don’t find out during the interview, they’ll find out later. It will come back to haunt you.

You’ve also worked on films where you had to spend long periods of time basically just following someone around, often through crazy environments. That’s a situation where you have to kind of learn to disappear and just make people forget you are there, even if you’re holding a giant camera. That’s a different skill.

Again, it has a lot to do with your personality. I can disappear in a room very quickly. As a cinematographer or as a director, it is very important how you move around people and that you are aware of not being in the way, ever. You learn how to never call attention to yourself. I’ve worked with cinematographers before and had to say things like, “No, you can’t go and put your camera in someone’s face like that.”

Working with a subject like Valentino, you’re basically just following him all over the world. The narrative is writing itself in front of you. With Halston, who died in 1990, you are sifting through archival materials and trying to piece together the story of this person’s life. What does that process look like? And how long did it take?

We started in April of 2017, and began with intensive research. We were reading everything that was available, creating a sort of database of Halston’s life and major life events. I was kind of rating them, like this was a three-star turning point in his life or this is more like a one-star moment and not something I want to go into. I had his life mapped out on a big board and then on another board I had a cast of characters I wanted to interview who were hopefully going to give me access to his different life events.

Then, you start talking to everyone on the phone, chasing all these people. Do you still have that contact? Do you know that person’s number? I found that part really fun. It was the first time that I was really going deep doing this sort of investigative work. I had done it to a certain extent with the Diana Vreeland film, but that was more on the post-production side. Also, Diana Vreeland was a much more transparent subject who had also written a book about her life, which had been sort of like the starting point.

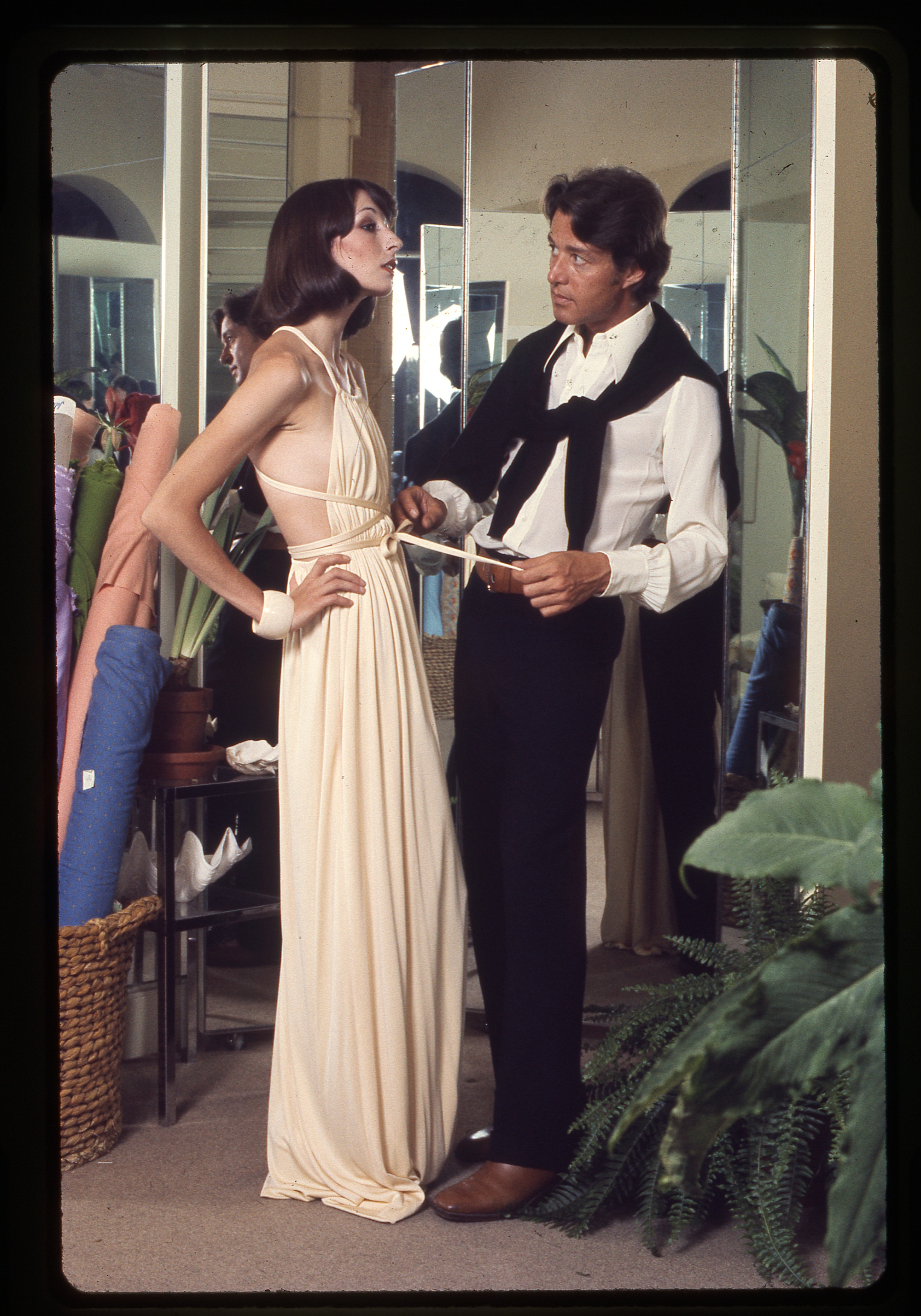

Halston and Angelica Huston ©Berry Berenson Perkins

Halston and Angelica Huston ©Berry Berenson Perkins

With Halston, there was no comprehensive interview. Every time he was asked to talk about his past in interviews—something that we show in the film—he’s like, “Enough of that history crap, I’m not interested in the past.” So, it was much more compelling—and much harder—to try to find that stuff out. There was also a lot of gossip around him, and for me a lot of trying to figure out what was real, what was not. Was his former partner, Victor Hugo, really his downfall? Or was he the spark of creativity that allowed Halston to thrive? It depends who you ask. Halston is a kind of an anti-hero noir character, never totally good, but never totally bad. I felt like I was really trying to investigate him and it took quite a while. Editing took a long time, almost a year.

You mentioned that you don’t necessarily want to be known as a fashion filmmaker, but you now have a pretty major footprint in that world. People are often very flippant about fashion, but your work gives a deep, respectful look at that world. You bring out the genius of these people and the true artistry of what they do. Has making these films altered your view of that world?

Definitely. I look at fashion very differently now. Halston, for example, never talked about his own work, or his craft. He let other people talk about that. His work made me interested in the dichotomy between artist and artisan. A lot of the criticism about him is that he was just a stylist, and that he just put women in flowy caftans and that anybody could do that. It’s very simple what he did. Simple, but not necessarily easy to do.

The designers who get the big retrospectives are—not to take away from their talent, because they are really talented—but they are people that make much bigger artistic statements. The clothes are obviously works of art because they are not really meant to be worn. Museums love that because it makes for big, splashy shows. Working on these films has really made me think about what is art, especially for a discipline like fashion, which is a little bit like film—both an art form but also something that is consumed.

So, I’m always on the fence. I grew up with art films and films that made big, artistic statements but were not necessarily always enjoyable to watch, you know? Then I came to the U.S. looking to make movies that would have a real rapport with the audience. It’s like Hitchcock used to say, “There’s no film without an audience.” You’re making the film for the audience. The film is actually in the audience’s eyes, it’s not an abstract thing. I think about this with Halston. He’s totally underappreciated for the way his clothes were so deeply constructed without being ostentatious. It was a much more pure way of designing. His clothes were really for the people who wore them. I think he really did just want to dress everyone.

Was making this movie and working with an actor the final push you needed to move away from documentaries and towards making a narrative film?

I think so. That was the idea from the beginning, to explore other forms of storytelling. You don’t want to be doing the same thing, over and over again. Biographical docs, as you said, it’s all talking heads and archival footage. I’m eager to make a fictional, narrative film. I don’t claim that I have at all mastered making documentaries, but it doesn’t excite me as much as trying something that I’ve never done before. I have screenplays in the works, and hopefully I can raise enough money to do a fiction film and continue to make docs also in parallel. There are so many different ways to tell stories, why not try all of them?

Frédéric Tcheng recommends:

I don’t know if you’ve seen Marlene, the documentary from the ’80s by Maximilian Schell, but it’s amazing. It’s a German documentary about Marlene Dietrich and was made while she was still alive, but she refused to go on camera. So, Maximilian Schell, who was also an actor and had a relationship with her, interviewed her during several afternoons in her home in Paris. She’s a total diva. She’s incredibly salty. She’s trying to direct and take over the movie, basically. Since he only had audio from their interviews and archival footage, which he used brilliantly, he still needed another element.

So he basically recreated the apartment in which they met. He recreated the filming and some of the editing of the film. He recreated his editing station so you see it in the film. It all makes for a very dynamic film, where you’re watching the film being made as it’s being made. And then eventually it goes into this big fireworks sequence where it’s like a dream where you have these Marlene Dietrich lookalikes and the smoke and these filmstrips everywhere and she goes into a tantrum.

It’s a brilliant film and it really made me think about the meta aspect of what I was doing in Halston. He stages his own process, and I think I was doing it similarly with Tavi in my film. She’s a surrogate for me doing the investigation, and sort of how I came to find out things about Halston and the twists and turns of the investigation. Also, the poster for Marlene is beautiful, it’s like Marlene Dietrich in a black and white tuxedo holding a Marlene Dietrich mask in color. I have the poster in my office.

Another thing I would recommend—that I haven’t read yet, actually—is Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask. I just discovered the book and the title recently because I was going to Japan. I was asking my friend for recommendations, and he pulled out that cover. I didn’t get to read it yet, but when I was finishing Halston the idea of a mask had been such a big theme in the film. Halston famously made masks for Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball and it is rumored that he might have been there himself, hiding behind a mask or something.

There are also these famous pictures of him with everyone in his studio wearing “Halston” masks. I think it’s John Cameron Mitchell who, in the Stonewall documentary, talked about how, as a kid growing up gay, you learn to lie. You’re forced to learn to lie at a very early age and basically to wear a mask and to not tell the truth about certain things, just for your own safety. Maybe now it’s changed, but certainly during Halston’s life, you see that a lot. You see how he had to conform or hide at certain points in order to succeed. Again, I’m sort of peeling the onion of who was Halston, and that was a big part of explaining how his grand persona was created. In many ways, it was a mask.