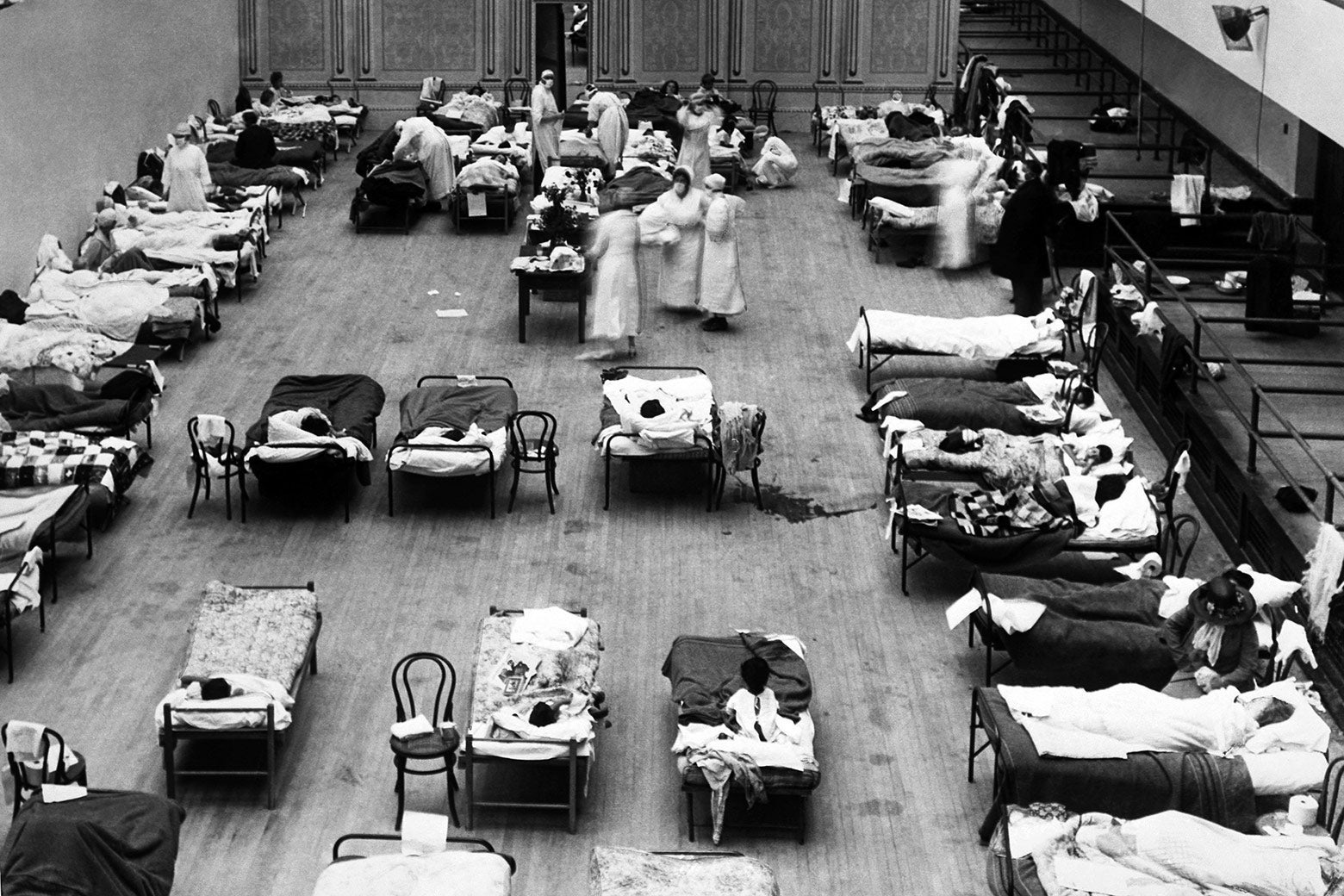

Last year, I wrote an anniversary piece about the “forgotten” 1918–19 flu pandemic, relying on the work of historians who’ve asked why such a huge event had so little effect on culture, policy, and public memory in the decades after that deadly flu strain burned itself out, leaving between 50 million and 100 million people dead. This year, as SARS-CoV-2 has forced the entire world into a terrifying and depressing alternate reality, I find this historical phenomenon even harder to understand. How could such a mind-bending, society-upending experience pass unremarked?

Enter Elizabeth Outka, a literary scholar whose fortuitously timed late-2019 book Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature explains quite a bit. The book looks at the small group of authors who addressed the pandemic head-on in their work but also argues that the work of some of the greats—T.S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, William Butler Yeats—was deeply affected by the flu in ways that aren’t so immediately obvious. Combining literary analysis with flu history and writing by flu survivors, Outka makes it clear that the pandemic wasn’t “forgotten”—it just went underground.

We spoke recently about the narrative impossibility of viruses, the mental health struggles of flu survivors, and the pervasive presence of something Outka calls “contagion guilt.” Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Rebecca Onion: There’s this idea that the 1918–19 pandemic had no impact—that this big thing that killed so many people was, somehow, a cultural nothing. Your book takes a different approach. Sometimes you’re talking about the clear impact of the pandemic, in the case of authors like William Maxwell or Katherine Anne Porter, and sometimes you’re identifying something that’s a little more nebulous or subterranean—the pandemic’s shadowy influence on the work of famous modernist writers. How did you come upon the idea of approaching flu’s memory this way?

Elizabeth Outka: Out of necessity, really. Diseases are recorded differently by our minds than something like a war. By their nature, diseases are highly individual. Even in a pandemic situation, you’re fighting your own internal battle with the virus, and it’s individual to you. Many, many people in a pandemic situation may be fighting that same battle, but it’s strangely both individualized and widespread.

A pandemic’s enormous impact is just not necessarily one that’s recorded in the ways we expect history to be recorded. You can record the economic loss; you can count the bodies—though that can be difficult, too. You can study the science of the virus, but there’s a difficulty with making the loss visible.

Of course, that’s one of the reasons we have memorials to people who died in wars—to take something not quite tangible and turn it into something people can see. I think with diseases that can be difficult to do. Diseases often impact bodies in ways that are difficult to define. Viruses are invisible, contagion can often be tracked generally but not specifically. I think these are all things that feed into this.

It’s difficult to memorialize a pandemic, because disease makes people feel helpless, and there’s very little we can do to make meaning from it. With war, even if you disagree with the war, you could at least argue about whether the death was worth it. Did this sacrifice keep a soldier’s family safe? With an infectious disease, if you die, your family is more likely to die. There’s no sacrificial structure to build around a loss of this kind. It’s simply tragedy.

My specialty is literature, and literature is especially good at capturing these elements of disease that are difficult to represent. Our bodies’ perception of the world depends on the health of the body and the experiences of that body. There’s that sort of invisible, strange conversation that happens between the body and the mind. Literature can capture that.

Literature can also capture the way a loss of a loved one lives on in all those very small gestures … you turn around and no one is there as you’re brushing your teeth—all these small, terrible, but largely invisible losses, except to the individual.

I want to ask about the overlapping nature of the flu pandemic and World War I. I think this is one of the common answers to the question of why the flu pandemic was “forgotten”: “We were at war.” But your book makes clear that people experienced these two tragedies as intertwined catastrophes. They had one understanding, that something bad is happening far away, and that intense focus on the war made it harder for people to process the fact that something else awful was also happening, close to hand.

I think there can be a real sense of surprise, as humans, that terrible things don’t happen in isolation. I wish it was the case that there were some law: “You can only have one major tragedy in a year, or a century!” But of course that’s not the way it is. There’s this sense of disbelief, overwhelm, and unfairness. “Aren’t we dealing with enough, here?”

The war was a very established story. People knew the characters, they knew the plot. It just took a while for people to get used to the idea that there was this other terrible mass death event unfolding, at home and on the front lines, everywhere.

You have a number of people in the book who are familiar modernist artists and writers, big names like T.S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, and W.B. Yeats, whose experiences with the flu were—you’re arguing—foundational to some of the art they made afterward. Can you talk a little bit about how that worked for these people?

These people had intimate ties with the flu and the pandemic, in different ways. I looked closely at the works they made that came out in the immediate aftermath, and I started to see that in their sensory and emotional atmosphere and climate, the flu had an influence.

A really important, big work of literature will always be about many things. “The Wasteland,” Mrs. Dalloway, “The Second Coming” … I’m not claiming that they are secretly only “about the pandemic.” I’m saying that like all great works, they are channeling the zeitgeist of the moment. The elements of the pandemic—the immediate experience of the body; the aftermath of it, how the body was exhausted—the works speak to this.

So for example, the Yeats poem “The Second Coming” [that’s the one that starts: “Turning and turning in the widening gyre/ The falcon cannot hear the falconer”]. That’s a canonical poem. He wrote it in 1919, and it has been read, quite rightly, as sort of a poem that captures the terrible aftermath of world war, and all the revolutions that were going on at the time, the political violence in Ireland, the Black-and-Tans … all this violence.

But in the weeks preceding his writing of the poem, his wife, George, who was pregnant, caught the virus and was very close to death. The highest death rates of the 1918–19 pandemic were among pregnant women—in some areas, it was an up to 70 percent death rate for these women. Just really terrible. He was watching this happen, and while his wife was convalescing, he sits down and writes “The Second Coming.”

When you read it through the lens of the pandemic, this other poem begins to emerge. You could see the way such a poem could resonate with people who’ve experienced this pandemic. This atmosphere—things are falling apart; the center cannot hold—an atmosphere of “mere anarchy, loosed upon the world.”

The threat in that first stanza is all in the passive voice, right? “The blood-dimmed tide is loosed”; “the ceremony of innocence is drowned.”* This amorphous threat coalesces into this vague sort of lurching beast at the end. It’s a terrific description of a pandemic.

Then specific imagery like the “blood-dimmed tide”—when one of the most frequent effects of this flu was bleeding from the nose, mouth, and ears. Just floods of blood. And then, the way people drowned in their beds, from their lungs filling up with fluid … and he has a line about the “ceremony of innocence being drowned,” when it’s his wife and unborn baby who were in the process of drowning like that.

Now, did Yeats have this at the top of his mind when he was writing the poem? We don’t know, but it certainly captures that horror, and that delirium.

Then there’s Virginia Woolf, who had influenza a number of times in the teens and ’20s, including right around 1918–19—so maybe she had the strain that caused the pandemic, though we don’t know. Her 1926 essay “On Being Ill,” which you write about alongside Mrs. Dalloway (1925), had such great observations about the way that being sick, which you would think would be a great subject for literature, is such an individual experience as to be almost indescribable.

Yes—and, we can’t know without doing the science, but the flu Woolf caught in 1919 seemed to damage her heart, so that would match up, since that was one of the common side effects of that particular strain.

I didn’t think about it before reading your book, but Mrs. Dalloway is a good exploration of the aftereffects of the flu virus in a sufferer who survived. That’s a really hard thing for history to represent—an encounter with that flu strain could wreck people for years, physically and emotionally, but that wreckage is a really hard thing to quantify on a social level.

In Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf shows all the subtle ways the flu still affects Clarissa Dalloway, as she’s walking through London years later. It affects her in ways that are visible to the novelist’s eye, but not necessarily visible to other people. Other people do see her condition, but I think what Woolf captures so well is the sense of isolation that was part of the aftermath. You’re haunted by the isolation you might have undergone during the illness, but also by the way the experience makes you “never the same again.” The flu, many survivors thought, created this before and after in a person’s life. Your perspective and your body have shifted in ways that are difficult to capture—but maybe not so difficult, if you happen to be Virginia Woolf!

You include some statistics about the number of suicides that might be attributed to the experience of the flu, but it’s so hard to count the neurological and mental health impact—the traumatic impact of going through something like this. People definitely recognized that flu survivors were prone to “melancholy,” at the time, but how can we know how many, or how to attribute it? I’ve been thinking about this a lot, when we hear about possible mental health effects of surviving a bad bout of COVID-19.

Yes, it’s really hard to know what’s causing what, to piece it out. In a way, it was quite appropriate to be depressed the year after the pandemic, right? It was fully understandable that people would be depressed and even suicidal, given the costs on every level.

The William Maxwell book They Came Like Swallows (1937), which is a straightforward, realist, completely heartbreaking depiction of what happens to a family when the flu kills the mother, brings up another aspect of the pandemic experience that you call “contagion guilt.” In that book, each surviving family member blames himself, in one way or another, for the mother’s death. This is something that is very heartbreaking to me, about our situation and about theirs—the idea that you might kill a loved one without knowing it.

Yes, there are two levels to it. First, this sort of haunting sense that maybe you gave a fatal disease to a loved one. Then, there’s the fact that you will never know for sure. I’m mindful of these wonderful little animated movies that make a virus visible—you can see the little green cloud, passed from the hand to the shoulder and from the shoulder to the sweater to the spoon to the person. And you say, “OK, this is how this happened.” But in real life, you don’t get to know. The absence of that ability means it’s quite difficult to confront that sort of guilt.

Imagine killing somebody in a war, where you meant to do it … that’s its own horrible thing to confront, but this, where you can’t be sure … where you didn’t want that to happen, and you’ll never quite know if it did or not … that makes it very difficult to cope with or address. We’re all feeling it, right now, in an anticipatory way: What if I went to see my older mother, and I gave her this virus without meaning to? What if I went to the grocery store to get something I don’t totally need, but would like to have, and I pass this to somebody?

Modernists are famously haunted by a sense of anxiety and guilt. The Maxwell book is a good example, but also, in Katherine Anne Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider, she is haunted in her dreams. Her boyfriend nurses her through influenza, and dies, and in her dreams, she sees him assaulted by arrows again and again … That dream is a great example of how that guilt might reside in somebody’s mind, not as a clear, upfront, kind of fear, but something that bubbles up in dreams and nightmares. The sense of silence that broods over the end of that story nicely captures that sense of guilt, and the realization that there’s not any place to put it.

Reading letters from survivors of the flu pandemic, one of the things that strikes me over and over again, that’s so moving, is that almost every one of them says, “I never forgot; I never forgot; I never forgot.” [Researching the book], I interviewed one 105-year-old woman who had the flu in Richmond, when she was 8. And in my cheery way, I said something like “Why do you think people forgot the flu?” And she looked at me like I was crazy. “We didn’t forget! We didn’t ignore it! We didn’t forget.” She’s 105, right? And she was like, “It never faded—not for us.”

Correction, May 4, 2020: This article originally misquoted a line from Yeats. He wrote, “The blood-dimmed tide is loosed,” not “The blood red tide is loosed”