Sex-Related Effects on Cardiac Development and Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Overview of Sex Differences in CVD

3. Cardiovascular Manifestations in Sex Chromosome Disorders

3.1. Turner Syndrome

3.2. Klinefelter Syndrome

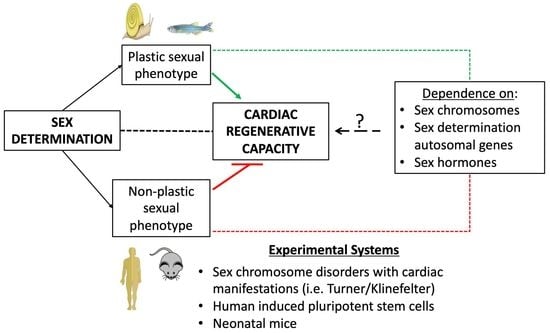

4. Cardiac Regeneration and Repair: Effects of Biological Sex

5. Role of E2 in Cardiac Injury and Repair

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Aparicio, H.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Cheng, S.; Delling, F.N.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2021 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e254–e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaignebet, L.; Kararigas, G. En route to precision medicine through the integration of biological sex into pharmacogenomics. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kararigas, G.; Seeland, U.; Barcena de Arellano, M.L.; Dworatzek, E.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Why the study of the effects of biological sex is important. Comment. Ann. Dell Ist. Super. Sanita 2016, 52, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Huang, C.; Liu, K.; Xu, G.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, Y.; Kararigas, G.; Geng, B.; Cui, Q. Large-scale in silico identification of drugs exerting sex-specific effects in the heart. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Meana, M.; Boengler, K.; Garcia-Dorado, D.; Hausenloy, D.J.; Kaambre, T.; Kararigas, G.; Perrino, C.; Schulz, R.; Ytrehus, K. Ageing, sex, and cardioprotection. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 5270–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Kararigas, G. Role of Biological Sex in the Cardiovascular-Gut Microbiome Axis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 8, 759735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franconi, F.; Campesi, I. Pharmacogenomics, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: Interaction with biological differences between men and women. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pei, J.; Harakalova, M.; Treibel, T.A.; Lumbers, R.T.; Boukens, B.J.; Efimov, I.R.; van Dinter, J.T.; Gonzalez, A.; Lopez, B.; El Azzouzi, H.; et al. H3K27ac acetylome signatures reveal the epigenomic reorganization in remodeled non-failing human hearts. Clin. Epigenetics 2020, 12, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Kararigas, G. Mechanistic Pathways of Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ober, C.; Loisel, D.A.; Gilad, Y. Sex-specific genetic architecture of human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iorga, A.; Cunningham, C.M.; Moazeni, S.; Ruffenach, G.; Umar, S.; Eghbali, M. The protective role of estrogen and estrogen receptors in cardiovascular disease and the controversial use of estrogen therapy. Biol. Sex Differ. 2017, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E. Estrogen signaling and cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murphy, E.; Steenbergen, C. Estrogen regulation of protein expression and signaling pathways in the heart. Biol. Sex Differ. 2014, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Menazza, S.; Murphy, E. The Expanding Complexity of Estrogen Receptor Signaling in the Cardiovascular System. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puglisi, R.; Mattia, G.; Care, A.; Marano, G.; Malorni, W.; Matarrese, P. Non-genomic Effects of Estrogen on Cell Homeostasis and Remodeling With Special Focus on Cardiac Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lowe, D.A.; Kararigas, G. Editorial: New Insights into Estrogen/Estrogen Receptor Effects in the Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beikoghli Kalkhoran, S.; Kararigas, G. Oestrogenic Regulation of Mitochondrial Dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, S.D.; Frangogiannis, N.G. The Biological Basis for Cardiac Repair After Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammation to Fibrosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daiou, A.; Petalidou, K.; Siokatas, G.; Papadopoulos, E.I.; Hatzistergos, K.E. Developmental and Regenerative Biology of Cardiomyocytes. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Xie, F.; Tian, L.; Fallah, S.; Babaei, F.; Manno, S.H.C.; Manno, F.A.M.; Zhu, L.; Wong, K.F.; Liang, Y.; et al. Estrogen accelerates heart regeneration by promoting the inflammatory response in zebrafish. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 245, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mitoh, S.; Yusa, Y. Extreme autotomy and whole-body regeneration in photosynthetic sea slugs. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R233–R234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, D.A.; Shine, R. The adaptive significance of temperature-dependent sex determination in a reptile. Nature 2008, 451, 566–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, I. Sex Determination and Sex Chromosomes in Amphibia. Sex. Dev. 2017, 11, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevant, I.; Nef, S. Genetic Control of Gonadal Sex Determination and Development. Trends Genet. 2019, 35, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kossack, M.E.; Draper, B.W. Genetic regulation of sex determination and maintenance in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2019, 134, 119–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura-Clapier, R.; Dworatzek, E.; Seeland, U.; Kararigas, G.; Arnal, J.F.; Brunelleschi, S.; Carpenter, T.C.; Erdmann, J.; Franconi, F.; Giannetta, E.; et al. Sex in basic research: Concepts in the cardiovascular field. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Colafella, K.M.M.; Denton, K.M. Sex-specific differences in hypertension and associated cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018, 14, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugiardini, R.; Bairey Merz, C.N. Angina with “normal” coronary arteries: A changing philosophy. JAMA 2005, 293, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Honda, S.; Asaumi, Y.; Yamane, T.; Nagai, T.; Miyagi, T.; Noguchi, T.; Anzai, T.; Goto, Y.; Ishihara, M.; Nishimura, K.; et al. Trends in the clinical and pathological characteristics of cardiac rupture in patients with acute myocardial infarction over 35 years. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e000984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berger, J.S.; Elliott, L.; Gallup, D.; Roe, M.; Granger, C.B.; Armstrong, P.W.; Simes, R.J.; White, H.D.; Van de Werf, F.; Topol, E.J.; et al. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2009, 302, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaccarino, V.; Parsons, L.; Every, N.R.; Barron, H.V.; Krumholz, H.M. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Participants. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marijon, E.; Uy-Evanado, A.; Reinier, K.; Teodorescu, C.; Narayanan, K.; Jouven, X.; Gunson, K.; Jui, J.; Chugh, S.S. Sudden cardiac arrest during sports activity in middle age. Circulation 2015, 131, 1384–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aurigemma, G.P.; Silver, K.H.; McLaughlin, M.; Mauser, J.; Gaasch, W.H. Impact of chamber geometry and gender on left ventricular systolic function in patients > 60 years of age with aortic stenosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 1994, 74, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.D.; Carroll, E.P.; Feldman, T.; Ward, D.M.; Lang, R.M.; McGaughey, D.; Karp, R.B. Sex-associated differences in left ventricular function in aortic stenosis of the elderly. Circulation 1992, 86, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Douglas, P.S.; Otto, C.M.; Mickel, M.C.; Labovitz, A.; Reid, C.L.; Davis, K.B. Gender differences in left ventricle geometry and function in patients undergoing balloon dilatation of the aortic valve for isolated aortic stenosis. NHLBI Balloon Valvuloplasty Registry. Br. Heart J. 1995, 73, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villar, A.V.; Llano, M.; Cobo, M.; Exposito, V.; Merino, R.; Martin-Duran, R.; Hurle, M.A.; Nistal, J.F. Gender differences of echocardiographic and gene expression patterns in human pressure overload left ventricular hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009, 46, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villari, B.; Campbell, S.E.; Schneider, J.; Vassalli, G.; Chiariello, M.; Hess, O.M. Sex-dependent differences in left ventricular function and structure in chronic pressure overload. Eur. Heart J. 1995, 16, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cleland, J.G.; Swedberg, K.; Follath, F.; Komajda, M.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Aguilar, J.C.; Dietz, R.; Gavazzi, A.; Hobbs, R.; Korewicki, J.; et al. The EuroHeart Failure survey programme-- a survey on the quality of care among patients with heart failure in Europe. Part 1: Patient characteristics and diagnosis. Eur. Heart J. 2003, 24, 442–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kararigas, G.; Dworatzek, E.; Petrov, G.; Summer, H.; Schulze, T.M.; Baczko, I.; Knosalla, C.; Golz, S.; Hetzer, R.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex-dependent regulation of fibrosis and inflammation in human left ventricular remodelling under pressure overload. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaignebet, L.; Kandula, M.M.; Lehmann, D.; Knosalla, C.; Kreil, D.P.; Kararigas, G. Sex-Specific Human Cardiomyocyte Gene Regulation in Left Ventricular Pressure Overload. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kararigas, G. Sex-biased mechanisms of cardiovascular complications in COVID-19. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, O.; Kararigas, G. Sex-Biased Vulnerability of the Heart to COVID-19. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 2332–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.S.; Carson, P.E.; Anand, I.S.; Rector, T.S.; Kuskowski, M.; Komajda, M.; McKelvie, R.S.; McMurray, J.J.; Zile, M.R.; Massie, B.M.; et al. Sex differences in clinical characteristics and outcomes in elderly patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: The Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (I-PRESERVE) trial. Circ. Heart Fail. 2012, 5, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beale, A.L.; Meyer, P.; Marwick, T.H.; Lam, C.S.P.; Kaye, D.M. Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology: Why Women Are Overrepresented in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2018, 138, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworatzek, E.; Baczko, I.; Kararigas, G. Effects of aging on cardiac extracellular matrix in men and women. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2016, 10, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbatini, A.R.; Kararigas, G. Menopause-Related Estrogen Decrease and the Pathogenesis of HFpEF: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbatini, A.R.; Kararigas, G. Estrogen-related mechanisms in sex differences of hypertension and target organ damage. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramariuc, D.; Rogge, B.P.; Lonnebakken, M.T.; Boman, K.; Bahlmann, E.; Gohlke-Barwolf, C.; Chambers, J.B.; Pedersen, T.R.; Gerdts, E. Sex differences in cardiovascular outcome during progression of aortic valve stenosis. Heart 2015, 101, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Selles, M.; Doughty, R.N.; Poppe, K.; Whalley, G.A.; Earle, N.; Tribouilloy, C.; McMurray, J.J.; Swedberg, K.; Kober, L.; Berry, C.; et al. Gender and survival in patients with heart failure: Interactions with diabetes and aetiology. Results from the MAGGIC individual patient meta-analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2012, 14, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, G.; Dworatzek, E.; Schulze, T.M.; Dandel, M.; Kararigas, G.; Mahmoodzadeh, S.; Knosalla, C.; Hetzer, R.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Maladaptive remodeling is associated with impaired survival in women but not in men after aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lonberg, N.C.; Nielsen, J. Sevesevskij-Turner’s syndrome or Turner’s syndrome. Hum. Genet. 1977, 38, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravholt, C.H.; Andersen, N.H.; Conway, G.S.; Dekkers, O.M.; Geffner, M.E.; Klein, K.O.; Lin, A.E.; Mauras, N.; Quigley, C.A.; Rubin, K.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: Proceedings from the 2016 Cincinnati International Turner Syndrome Meeting. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 177, G1–G70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotters-Katz, S.K.; Humphrey, W.M.; Senz, K.L.; Lee, V.R.; Shaffer, B.L.; Caughey, A.B. The Effects of Turner Syndrome, 45,X on Obstetric and Neonatal Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Evaluation. Am. J. Perinatol. 2016, 33, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Egmond, H.; Orye, E.; Praet, M.; Coppens, M.; Devloo-Blancquaert, A. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome and 45X karyotype. Br. Heart J. 1988, 60, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miyabara, S.; Nakayama, M.; Suzumori, K.; Yonemitsu, N.; Sugihara, H. Developmental analysis of cardiovascular system of 45,X fetuses with cystic hygroma. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1997, 68, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surerus, E.; Huggon, I.C.; Allan, L.D. Turner’s syndrome in fetal life. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 22, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donadille, B.; Rousseau, A.; Zenaty, D.; Cabrol, S.; Courtillot, C.; Samara-Boustani, D.; Salenave, S.; Monnier-Cholley, L.; Meuleman, C.; Jondeau, G.; et al. Cardiovascular findings and management in Turner syndrome: Insights from a French cohort. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 167, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bondy, C.; Bakalov, V.K.; Cheng, C.; Olivieri, L.; Rosing, D.R.; Arai, A.E. Bicuspid aortic valve and aortic coarctation are linked to deletion of the X chromosome short arm in Turner syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2013, 50, 662–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Corbitt, H.; Gutierrez, J.; Silberbach, M.; Maslen, C.L. The genetic basis of Turner syndrome aortopathy. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2019, 181, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbitt, H.; Morris, S.A.; Gravholt, C.H.; Mortensen, K.H.; Tippner-Hedges, R.; Silberbach, M.; Maslen, C.L.; Gen, T.A.C.R.I. TIMP3 and TIMP1 are risk genes for bicuspid aortic valve and aortopathy in Turner syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroner, B.L.; Tolunay, H.E.; Basson, C.T.; Pyeritz, R.E.; Holmes, K.W.; Maslen, C.L.; Milewicz, D.M.; LeMaire, S.A.; Hendershot, T.; Desvigne-Nickens, P.; et al. The National Registry of Genetically Triggered Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Cardiovascular Conditions (GenTAC): Results from phase I and scientific opportunities in phase II. Am. Heart J. 2011, 162, 627–632.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Altinbas, L.; Bormann, N.; Lehmann, D.; Jeuthe, S.; Wulsten, D.; Kornak, U.; Robinson, P.N.; Wildemann, B.; Kararigas, G. Assessment of Bones Deficient in Fibrillin-1 Microfibrils Reveals Pronounced Sex Differences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bhushan, R.; Altinbas, L.; Jager, M.; Zaradzki, M.; Lehmann, D.; Timmermann, B.; Clayton, N.P.; Zhu, Y.; Kallenbach, K.; Kararigas, G.; et al. An integrative systems approach identifies novel candidates in Marfan syndrome-related pathophysiology. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2526–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Nava, F.; Lanes, R. Epigenetics in Turner syndrome. Clin. Epigenetics 2018, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, R.; Hao, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, M.; Li, W.; Li, R.; Yu, J.; Xiao, J.; Wu, J. Gene expression analysis of induced pluripotent stem cells from aneuploid chromosomal syndromes. BMC Genom. 2013, 14 (Suppl. 5), S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rajpathak, S.N.; Vellarikkal, S.K.; Patowary, A.; Scaria, V.; Sivasubbu, S.; Deobagkar, D.D. Human 45,X fibroblast transcriptome reveals distinct differentially expressed genes including long noncoding RNAs potentially associated with the pathophysiology of Turner syndrome. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trolle, C.; Nielsen, M.M.; Skakkebaek, A.; Lamy, P.; Vang, S.; Hedegaard, J.; Nordentoft, I.; Orntoft, T.F.; Pedersen, J.S.; Gravholt, C.H. Widespread DNA hypomethylation and differential gene expression in Turner syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seenundun, S.; Rampalli, S.; Liu, Q.C.; Aziz, A.; Palii, C.; Hong, S.; Blais, A.; Brand, M.; Ge, K.; Dilworth, F.J. UTX mediates demethylation of H3K27me3 at muscle-specific genes during myogenesis. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 1401–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, S.K. UTX, a histone H3-lysine 27 demethylase, acts as a critical switch to activate the cardiac developmental program. Dev. Cell 2012, 22, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, W.; Sheng, X.; Dorr, K.M.; Hutton, J.E.; Emerson, J.I.; Davies, H.A.; Andrade, T.D.; Wasson, L.K.; Greco, T.M.; Hashimoto, Y.; et al. Cardiac proteomics reveals sex chromosome-dependent differences between males and females that arise prior to gonad formation. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 3019–3034.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashworth, A.; Rastan, S.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Kay, G. X-chromosome inactivation may explain the difference in viability of XO humans and mice. Nature 1991, 351, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disteche, C.M. Escapees on the X chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 14180–14182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Disteche, C.M.; Filippova, G.N.; Tsuchiya, K.D. Escape from X inactivation. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2002, 99, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrel, L.; Willard, H.F. X-inactivation profile reveals extensive variability in X-linked gene expression in females. Nature 2005, 434, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.; Fan, W.; Zhao, P.; Chan, Y.C.; Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Modeling abnormal early development with induced pluripotent stem cells from aneuploid syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondy, C.A.; Ceniceros, I.; Van, P.L.; Bakalov, V.K.; Rosing, D.R. Prolonged rate-corrected QT interval and other electrocardiogram abnormalities in girls with Turner syndrome. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e1220–e1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, S.B.; Korecki, A.J.; Baldry, S.E.L.; Yang, C.; Tosefsky, K.; Balaton, B.P.; Simpson, E.M.; Brown, C.J. How do genes that escape from X-chromosome inactivation contribute to Turner syndrome? Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2019, 181, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florijn, B.W.; Bijkerk, R.; van der Veer, E.P.; van Zonneveld, A.J. Gender and cardiovascular disease: Are sex-biased microRNA networks a driving force behind heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in women? Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allybocus, Z.A.; Wang, C.; Shi, H.; Wu, Q. Endocrinopathies and cardiopathies in patients with Turner syndrome. Climacteric 2018, 21, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, K.A.; Skakkebaek, A.; Host, C.; Gravholt, C.H.; Bojesen, A. Clinical review: Klinefelter syndrome--a clinical update. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bojesen, A.; Kristensen, K.; Birkebaek, N.H.; Fedder, J.; Mosekilde, L.; Bennett, P.; Laurberg, P.; Frystyk, J.; Flyvbjerg, A.; Christiansen, J.S.; et al. The metabolic syndrome is frequent in Klinefelter’s syndrome and is associated with abdominal obesity and hypogonadism. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andersen, N.H.; Bojesen, A.; Kristensen, K.; Birkebaek, N.H.; Fedder, J.; Bennett, P.; Christiansen, J.S.; Gravholt, C.H. Left ventricular dysfunction in Klinefelter syndrome is associated to insulin resistance, abdominal adiposity and hypogonadism. Clin. Endocrinol. 2008, 69, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquali, D.; Arcopinto, M.; Renzullo, A.; Rotondi, M.; Accardo, G.; Salzano, A.; Esposito, D.; Saldamarco, L.; Isidori, A.M.; Marra, A.M.; et al. Cardiovascular abnormalities in Klinefelter syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojesen, A.; Juul, S.; Gravholt, C.H. Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome: A national registry study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poss, K.D.; Wilson, L.G.; Keating, M.T. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science 2002, 298, 2188–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porrello, E.R.; Mahmoud, A.I.; Simpson, E.; Hill, J.A.; Richardson, J.A.; Olson, E.N.; Sadek, H.A. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science 2011, 331, 1078–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, E.; Zhao, M.; Chong, Z.; Fan, C.; Tang, Y.; Hunter, J.D.; Borovjagin, A.V.; Walcott, G.P.; Chen, J.Y.; et al. Regenerative Potential of Neonatal Porcine Hearts. Circulation 2018, 138, 2809–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, E.; Sadek, H.A.; Bergmann, O. Cardiomyocyte renewal in the human heart: Insights from the fall-out. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bergmann, O.; Bhardwaj, R.D.; Bernard, S.; Zdunek, S.; Barnabe-Heider, F.; Walsh, S.; Zupicich, J.; Alkass, K.; Buchholz, B.A.; Druid, H.; et al. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 2009, 324, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- King, A.C.; Gut, M.; Zenker, A.K. Shedding new light on early sex determination in zebrafish. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 4143–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, D.; Luzio, A.; Coimbra, A.M. Zebrafish sex differentiation and gonad development: A review on the impact of environmental factors. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 191, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, W.C.; Bartfai, R.; Lim, Z.; Sreenivasan, R.; Siegfried, K.R.; Orban, L. Polygenic sex determination system in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pullen, A.B.; Kain, V.; Serhan, C.N.; Halade, G.V. Molecular and Cellular Differences in Cardiac Repair of Male and Female Mice. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenburg, J.S.; Clark, R.M.; Coffman, B.; Sharma, G.; Hathaway, H.J.; Prossnitz, E.R.; Howdieshell, T.R. Sex differences in murine myocutaneous flap revascularization. Wound Repair Regen. 2020, 28, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broughton, K.M.; Wang, B.J.; Firouzi, F.; Khalafalla, F.; Dimmeler, S.; Fernandez-Aviles, F.; Sussman, M.A. Mechanisms of Cardiac Repair and Regeneration. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straface, E.; Gambardella, L.; Pagano, F.; Angelini, F.; Ascione, B.; Vona, R.; De Falco, E.; Cavarretta, E.; Russa, R.; Malorni, W.; et al. Sex Differences of Human Cardiac Progenitor Cells in the Biological Response to TNF-alpha Treatment. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 4790563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, M.; Tsai, B.M.; Crisostomo, P.R.; Meldrum, D.R. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling resistance in the female myocardium during ischemia. Circulation 2006, 114, I282–I289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fuentes, N.; Silveyra, P. Estrogen receptor signaling mechanisms. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2019, 116, 135–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kararigas, G. Oestrogenic contribution to sex-biased left ventricular remodelling: The male implication. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 343, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, J.S.; Montagnoli, T.L.; Rocha, B.S.; Tacco, M.; Marinho, S.C.P.; Zapata-Sudo, G. Estrogen Receptors: Therapeutic Perspectives for the Treatment of Cardiac Dysfunction after Myocardial Infarction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, A.M.; Murphy, E.; Sun, J. Estrogen receptor activation and cardioprotection in ischemia reperfusion injury. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2010, 20, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schubert, C.; Raparelli, V.; Westphal, C.; Dworatzek, E.; Petrov, G.; Kararigas, G.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Reduction of apoptosis and preservation of mitochondrial integrity under ischemia/reperfusion injury is mediated by estrogen receptor beta. Biol. Sex Differ. 2016, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mahmoodzadeh, S.; Dworatzek, E. The Role of 17beta-Estradiol and Estrogen Receptors in Regulation of Ca2+ Channels and Mitochondrial Function in Cardiomyocytes. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sickinghe, A.A.; Korporaal, S.J.A.; den Ruijter, H.M.; Kessler, E.L. Estrogen Contributions to Microvascular Dysfunction Evolving to Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ventura-Clapier, R.; Piquereau, J.; Veksler, V.; Garnier, A. Estrogens, Estrogen Receptors Effects on Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle Mitochondria. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, B.; Miller, V.M.; Miller, J.D. Influences of Sex and Estrogen in Arterial and Valvular Calcification. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kararigas, G.; Fliegner, D.; Forler, S.; Klein, O.; Schubert, C.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Klose, J.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Comparative Proteomic Analysis Reveals Sex and Estrogen Receptor beta Effects in the Pressure Overloaded Heart. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 5829–5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kararigas, G.; Nguyen, B.T.; Jarry, H. Estrogen modulates cardiac growth through an estrogen receptor alpha-dependent mechanism in healthy ovariectomized mice. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014, 382, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kararigas, G.; Nguyen, B.T.; Zelarayan, L.C.; Hassenpflug, M.; Toischer, K.; Sanchez-Ruderisch, H.; Hasenfuss, G.; Bergmann, M.W.; Jarry, H.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Genetic background defines the regulation of postnatal cardiac growth by 17beta-estradiol through a beta-catenin mechanism. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kararigas, G.; Fliegner, D.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Role of the estrogen/estrogen-receptor-beta axis in the genomic response to pressure overload-induced hypertrophy. Physiol. Genom. 2011, 43, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Ruderisch, H.; Queiros, A.M.; Fliegner, D.; Eschen, C.; Kararigas, G.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex-specific regulation of cardiac microRNAs targeting mitochondrial proteins in pressure overload. Biol. Sex Differ. 2019, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duft, K.; Schanz, M.; Pham, H.; Abdelwahab, A.; Schriever, C.; Kararigas, G.; Dworatzek, E.; Davidson, M.M.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Morano, I.; et al. 17beta-Estradiol-induced interaction of estrogen receptor alpha and human atrial essential myosin light chain modulates cardiac contractile function. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2017, 112, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.; Collins, B.C.; Colson, B.A.; Kararigas, G.; Lowe, D.A. Estradiol modulates myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation and contractility in skeletal muscle of female mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 310, E724–E733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mahmoodzadeh, S.; Pham, T.H.; Kuehne, A.; Fielitz, B.; Dworatzek, E.; Kararigas, G.; Petrov, G.; Davidson, M.M.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. 17beta-Estradiol-induced interaction of ERalpha with NPPA regulates gene expression in cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 96, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Kararigas, G.; Jarry, H. Dose-dependent effects of a genistein-enriched diet in the heart of ovariectomized mice. Genes Nutr. 2012, 8, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Kararigas, G.; Wuttke, W.; Jarry, H. Long-term treatment of ovariectomized mice with estradiol or phytoestrogens as a new model to study the role of estrogenic substances in the heart. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kararigas, G.; Bito, V.; Tinel, H.; Becher, E.; Baczko, I.; Knosalla, C.; Albrecht-Kupper, B.; Sipido, K.R.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Transcriptome characterization of estrogen-treated human myocardium identifies Myosin regulatory light chain interacting protein as a sex-specific element influencing contractile function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kararigas, G.; Becher, E.; Mahmoodzadeh, S.; Knosalla, C.; Hetzer, R.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex-specific modification of progesterone receptor expression by 17beta-oestradiol in human cardiac tissues. Biol. Sex Differ. 2010, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hein, S.; Hassel, D.; Kararigas, G. The Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Is a Relevant Model for Studying Sex-Specific Effects of 17beta-Estradiol in the Adult Heart. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fliegner, D.; Schubert, C.; Penkalla, A.; Witt, H.; Kararigas, G.; Dworatzek, E.; Staub, E.; Martus, P.; Ruiz Noppinger, P.; Kintscher, U.; et al. Female sex and estrogen receptor-beta attenuate cardiac remodeling and apoptosis in pressure overload. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 298, R1597–R1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiros, A.M.; Eschen, C.; Fliegner, D.; Kararigas, G.; Dworatzek, E.; Westphal, C.; Sanchez Ruderisch, H.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex- and estrogen-dependent regulation of a miRNA network in the healthy and hypertrophied heart. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 169, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Steenbergen, C. Gender-based differences in mechanisms of protection in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007, 75, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sivasinprasasn, S.; Palee, S.; Chattipakorn, K.; Jaiwongkum, T.; Apaijai, N.; Pratchayasakul, W.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Chattipakorn, N. N-acetylcysteine with low-dose estrogen reduces cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 242, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, P.; Eurell, T.E.; Cotthaus, R.; Jeffery, E.H.; Bahr, J.M.; Gross, D.R. Effect of estrogen on global myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in female rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000, 279, H2766–H2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, T.M.; Su, S.F.; Tsai, C.C.; Lee, Y.T.; Tsai, C.H. Cardioprotective effects of 17 beta-estradiol produced by activation ofmitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ Channels in canine hearts. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2000, 32, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Smith, K.; Yu, Q.; Miller, C.; Singh, K.; Sen, C.K. Mitochondrial connexin 43 in sex-dependent myocardial responses and estrogen-mediated cardiac protection following acute ischemia/reperfusion injury. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2019, 115, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Liu, H.; Kim, J.K. Estrogen Protects the Female Heart from Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury through Manganese Superoxide Dismutase Phosphorylation by Mitochondrial p38beta at Threonine 79 and Serine 106. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Arenas, I.A.; Armstrong, S.J.; Plahta, W.C.; Xu, H.; Davidge, S.T. Estrogen improves cardiac recovery after ischemia/reperfusion by decreasing tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 69, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pelzer, T.; Neumann, M.; de Jager, T.; Jazbutyte, V.; Neyses, L. Estrogen effects in the myocardium: Inhibition of NF-kappaB DNA binding by estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 286, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelzer, T.; Schumann, M.; Neumann, M.; deJager, T.; Stimpel, M.; Serfling, E.; Neyses, L. 17beta-estradiol prevents programmed cell death in cardiac myocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 268, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menazza, S.; Sun, J.; Appachi, S.; Chambliss, K.L.; Kim, S.H.; Aponte, A.; Khan, S.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Katzenellenbogen, B.S.; Shaul, P.W.; et al. Non-nuclear estrogen receptor alpha activation in endothelium reduces cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2017, 107, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.J.; Ornatsky, O.; Stewart, D.J.; Picard, P.; Dawood, F.; Wen, W.H.; Liu, P.P.; Webb, D.J.; Monge, J.C. Effects of estrogen replacement on infarct size, cardiac remodeling, and the endothelin system after myocardial infarction in ovariectomized rats. Circulation 2000, 102, 2983–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patten, R.D.; Karas, R.H. Estrogen replacement and cardiomyocyte protection. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2006, 16, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patten, R.D.; Pourati, I.; Aronovitz, M.J.; Baur, J.; Celestin, F.; Chen, X.; Michael, A.; Haq, S.; Nuedling, S.; Grohe, C.; et al. 17beta-estradiol reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vivo and in vitro via activation of phospho-inositide-3 kinase/Akt signaling. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simoncini, T.; Hafezi-Moghadam, A.; Brazil, D.P.; Ley, K.; Chin, W.W.; Liao, J.K. Interaction of oestrogen receptor with the regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature 2000, 407, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Tang, Z.P.; Zhao, W.; Cong, B.H.; Lu, J.Q.; Tang, X.L.; Li, X.H.; Zhu, X.Y.; Ni, X. MiR-22/Sp-1 Links Estrogens With the Up-Regulation of Cystathionine gamma-Lyase in Myocardium, Which Contributes to Estrogenic Cardioprotection Against Oxidative Stress. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 2124–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, S.A.; Claudio, E.R.G.; Mengal, V.; Brasil, G.A.; Merlo, E.; Podratz, P.L.; Graceli, J.B.; Gouvea, S.A.; de Abreu, G.R. Estrogen Therapy Worsens Cardiac Function and Remodeling and Reverses the Effects of Exercise Training After Myocardial Infarction in Ovariectomized Female Rats. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van Eickels, M.; Patten, R.D.; Aronovitz, M.J.; Alsheikh-Ali, A.; Gostyla, K.; Celestin, F.; Grohe, C.; Mendelsohn, M.E.; Karas, R.H. 17-beta-estradiol increases cardiac remodeling and mortality in mice with myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Hu, S. Effects of estrogen on diverse stem cells and relevant intracellular mechanisms. Sci. China Life Sci. 2010, 53, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihai, M.C.; Popa, M.A.; Suica, V.I.; Antohe, F.; Jackson, E.K.; Simionescu, M.; Dubey, R.K. Mechanism of 17beta-estradiol stimulated integration of human mesenchymal stem cells in heart tissue. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2019, 133, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erwin, G.S.; Crisostomo, P.R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Markel, T.A.; Guzman, M.; Sando, I.C.; Sharma, R.; Meldrum, D.R. Estradiol-treated mesenchymal stem cells improve myocardial recovery after ischemia. J. Surg. Res. 2009, 152, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwakura, A.; Shastry, S.; Luedemann, C.; Hamada, H.; Kawamoto, A.; Kishore, R.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, G.; Silver, M.; Thorne, T.; et al. Estradiol enhances recovery after myocardial infarction by augmenting incorporation of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells into sites of ischemia-induced neovascularization via endothelial nitric oxide synthase-mediated activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Circulation 2006, 113, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Gu, H.; Turrentine, M.; Wang, M. Estradiol treatment promotes cardiac stem cell (CSC)-derived growth factors, thus improving CSC-mediated cardioprotection after acute ischemia/reperfusion. Surgery 2014, 156, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Kang, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, A.; Zhao, Q.; Li, H. 17beta-estradiol promotes recovery after myocardial infarction by enhancing homing and angiogenic capacity of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells through ERalpha-SDF-1/CXCR4 crosstalking. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2018, 50, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, J.; Ye, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, A.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, Q. 17beta-Estradiol enhances the recruitment of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells into infarcted myocardium by inducing CXCR4 expression. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 162, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.S.; Luo, L.; Baba, S.; Li, T.S. Estrogen is required for maintaining the quality of cardiac stem cells. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronen, D.; Benvenisty, N. Sex-dependent gene expression in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leri, A.; Kajstura, J.; Anversa, P. Cardiac stem cells and mechanisms of myocardial regeneration. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 1373–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

|

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siokatas, G.; Papatheodorou, I.; Daiou, A.; Lazou, A.; Hatzistergos, K.E.; Kararigas, G. Sex-Related Effects on Cardiac Development and Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd9030090

Siokatas G, Papatheodorou I, Daiou A, Lazou A, Hatzistergos KE, Kararigas G. Sex-Related Effects on Cardiac Development and Disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2022; 9(3):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd9030090

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiokatas, Georgios, Ioanna Papatheodorou, Angeliki Daiou, Antigone Lazou, Konstantinos E. Hatzistergos, and Georgios Kararigas. 2022. "Sex-Related Effects on Cardiac Development and Disease" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 9, no. 3: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd9030090