How Adler & Sullivan’s Buildings Paved the Way for Modern Skylines

In 1952, a photography student named Richard Nickel began to document the works of Chicago architects Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan within the context of aging neighborhoods, crude remodeling, and outright demolition. Of the 256 buildings designed by the late-19th- and early-20th-century architects, both as a team during their 15- year partnership and as individuals, only about 30 still stand. Most were demolished in the ’50s and ’60s during the age of urban renewal. Of these, the majority were in Chicago, where their firm, Adler & Sullivan, was based.

Though Nickel’s documentation of Adler & Sullivan works began in a graduate-level photography course at Chicago’s Institute of Design (now the Illinois Institute of Technology) instructed by photographer Aaron Siskind, he continued cataloging the architects’ projects into the early ’70s, with plans to produce a book. In 1972, however, Nickel died in an accident at the demolition site of the Sullivan-designed Chicago Stock Exchange building. Upon his passing, Nickel’s friends and colleagues formed the Richard Nickel Committee to retrieve his archive and continue his project research. In late 2010, the University of Chicago Press published The Complete Architecture of Adler & Sullivan, a hefty book with more than 800 photographs by Nickel, Siskind, and other noted photographers, as well as architectural plans and essays that catalog the oeuvre of Adler and Sullivan (the latter often called the "father of skyscrapers" and "father of modernism").

A glass window panel from the office of Adler & Sullivan, a prolific Chicago firm run by architects Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan in the 1880s and 1890s.

Chicago preservation architect Ward Miller was the executive director of the committee that brought Nickel’s work to fruition and coauthored the 2010 publication. I talked to him about the significance and influence Adler and Sullivan’s buildings, and why Nickel’s documentation of them is something everyone ought to know about.

Dwell: What was the relationship between Adler and Sullivan during their 15 years of practicing together? Their roles? How did it affect their architecture?

Ward Miller: Adler & Sullivan are most associated with being an innovative and progressive architectural practice; forwarding the idea of an American style and expressing this in a truly modern format. Their work was widely published and at the forefront of building construction. Their buildings—especially their multipurpose structures, like the Auditorium Building and Auditorium Theater in Chicago—were unequaled. The expression of a tall building, its structure with a definite base, middle section or shaft, and top or cornice was a new approach for the high-building design. These types of tall structures developed into a format. It’s most evident in expression in the Wainwright Building in St. Louis and later the Guaranty Building in Buffalo, New York. Even today, the vertical expression of a building employs these design principals.

Architect Louis Sullivan (1856-1924) is often regarded as "father of skyscrapers" and "father of modernism." He was a mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright, and he and his firm partner Dankmar Adler (not pictured) were leaders in the Chicago School of Architecture at the turn of the 20th century.

Sullivan attended the École des Beaux-Arts but his work is distinctly American. What were the influences that caused him to look inward toward America, rather than outward toward Europe, for his designs?

Louis Sullivan was very much influenced by the writings of Thoreau and Whitman and by his experiences and study of nature—the seed germ, the seed pod and its development and flowering—which he related to the expression of a building. This was an approach that was not evident prior in such a format and scale in architecture.

Adler & Sullivan’s Wainwright Building in St. Louis, Missouri, was built between 1890 and 1891. It’s listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is considered a highly influential prototype of the modern high-rise office building.

Describe the era in which Adler & Sullivan practiced, and how that affected their designs.

The era in which they were practicing in the 1880s and 1890s was a time when buildings became taller, and the expression of that building style was still a great problem for architects. Often architects would reach to a more conventional or historical style and continue to stack floors onto these buildings, making a three-story building a six-story building with the same type of expression.

Buildings designed by the duo were marked by Sullivan’s inventive ornamentation, which relied not on traditional precedents like classical columns and pediments, but instead incorporated natural and organic forms (as seen in the Wainwright Building’s facade detailing, pictured above).

Of the firm’s hundreds of commissions, which were most significant and why?

The most significant early example would be the multipurpose Auditorium Building in Chicago that combined a 4,500-seat theater and opera house, a hotel, and an office building with some retail. The mammoth scale, ambitious program and its implementation, along with its tremendous success and its sheer beauty established the firm on a national scale. The theater’s acoustics, sight lines, innovations, and integration of functions made it the foremost of the firm’s work, and one of the most important buildings of its age.

The Adler & Sullivan-designed Auditorium Building in Chicago was built 1886 and 1890—with a young Frank Lloyd Wright as draftsman—and is one of the firm’s best-known projects. When completed, it was the largest, tallest, priciest and heaviest building of its time.

The Schiller/Garrick was also important because it incorporated a theater, office building, and retail on a much smaller site, but also used advances in technology, steel-frame construction, and foundation footings to achieve the 17-story solution—the tallest building in the firm’s portfolio. The Chicago Stock Exchange Building of 1894 was a beautiful expression of an office building, with its undulating facade, surface decoration, and clarity of structure.

Adler & Sullivan designed the 1891 Schiller Building (later called the Garrick Theater) for the German Opera Company—hence the series of terra-cotta busts depicting German figures on its facade. At the time of its construction, the building was among Chicago’s tallest. In 1961, it was replaced with a parking structure.

Other great structures are the Wainwright Building for its soaring vertical expression, along with its sister building, the Guaranty Building. There’s the Sullivan-designed Bayard-Condict Building in New York City, and the Schlesinger & Mayer Building (later known as Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Store)—also designed just by Sullivan—is the clearest expression of the steel frame and materials. The jewel box banks and commissions throughout the Midwest are also extremely important on a number of levels and are often viewed as works of art, as well as architecture.

The 12-story Bayard-Condict Building in New York City, built between 1897 and 1899 in the Chicago School architectural style, was the only New York building Sullivan designed. Architect Lyndon P. Smith assisted him on the project.

Of those that remain, which is most important, and why?

All of the remaining buildings by Adler & Sullivan, as well as Adler alone and Sullivan alone are very important. With about 30 structures of the 256 commissions left, each represents a phase in the full body of work. Each tells a story and gives insight into the firm’s work. The commercial buildings are all very important. And residential projects in Chicago, like the Charnley-Persky House [by Sullivan with assistance from Wright as draftsman] and the Row Houses for Ann Halsted [by Adler & Sullivan], even the small Krause Music Store [Sullivan’s last commission], all hold special qualities that make them landmark structures.

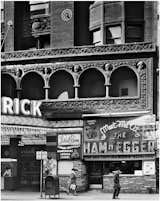

Photographer Richard Nickel documented Adler & Sullivan’s most famous commissions, as well as their lesser-known projects, including the 1883 Knisley Store in Chicago.

Who was Richard Nickel and why should we care?

Nickel was an architectural photographer who became interested in the work of Adler and Sullivan while studying at the Institute of Design in Chicago. He often focused on the details, the ornaments, and the soaring qualities of the structures. He looked beyond the soot and grime of the urban cities of the ’50s and ’60s and began photo-documenting the buildings in great detail, changing the views of many citizens as to why these buildings, sometimes considered obsolete, were really important.

The effort to save Adler & Sullivan’s Schiller/Garrick Building was the beginning of the preservation movement in America, along with efforts in New York to save the former Pennsylvania Station [designed by McKim, Mead & White].

A view of the proscenium in the Schiller Building (aka Garrick Theater) in Chicago. In 1960, photographer Richard Nickel launched a major preservation campaign to save the Adler & Sullivan-designed structure from demolition. After permits were issued, he shifted his efforts to recuperating hundreds of terra-cotta and plaster ornaments from the interior and facade.

Could you comment on his understanding of the architects’ work?

Nickel was astonished by the beauty of the buildings, and in their destruction could see the concealed structure exposed. He was an artist and there was a great interpretation of Adler & Sullivan’s work as it was under demise. There was a certain clarity that was revealed while these buildings were being dissembled piece by piece, with Nickel removing the ornamental terra-cotta cladding for preservation, along with the wrecking companies whittling down these seminal masterpieces—revealing works of art in their own right.

Besides photography, what else is he known for?

Nickel is also known for his efforts to bring about an awareness of the importance of the great buildings of the Commercial Style, sometimes referred to as the Chicago Commercial Style, the Chicago School, or the Chicago School of Architecture. He was one of several public figures that protested the planned destruction of important architectural landmarks, most notably the Schiller/Garrick Building. Nickel actually lost his life in an accident within the walls of the Chicago Stock Exchange Building as it was being demolished.

Built in 1908 in Owatonna, Minnesota, the National Farmers’ Bank was the first of eight jewel box banks designed by Sullivan in the Midwest in the early 20th century. The decorative terra-cotta elements were designed by Prairie School architect George Elmslie, who also detailed the ornamentation for Adler & Sullivan’s Wainright and Schlesinger & Mayer Buildings.

Where are all the artifacts that he salvaged today?

Many of the architectural fragments salvaged by Nickel are at Southern Illinois University’s campus and library in Edwardsville, Illinois. These are fragments from his own personal collection that he sold to the university as it was planning a new campus. Other fragments from the Garrick and the Chicago Stock Exchange are in both public and private collections around the world, including several major art museums from the Art Institute of Chicago, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

The Sullivan-designed National Farmers’ Bank is widely recognized as one of the earliest examples of the Prairie School architectural style in America.

What was the intent of publishing the book?

The intent of the book was to show Adler & Sullivan’s full body of work and to introduce many that had been forgotten or demolished. There’s the catalogue raisonné section...the introductory essays are to familiarize the reader with the office, its strides in architecture, and the architecture and business climate of the day. We are hopeful that the images are looked upon as conveying the design principals of the architects, but also as beautiful images in their own right. We are also hopeful that the book will further positively impact the preservation of other structures that are not yet recognized as landmarks.

We love the products we feature and hope you do, too. If you buy something through a link on the site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Related Reading:

Published

Last Updated

Topics

LifestyleGet the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.