It’s worse than we thought.

Just one day after disclosing a secret court order between the National Security Agency (NSA) and Verizon, The Guardian and The Washington Post both published secret presentation slides revealing a previously undisclosed massive surveillance program called PRISM. The program has the capability to collect data “directly from the servers” of major American tech companies, including Microsoft, Google, Apple, Facebook, and Yahoo. (Dropbox is said to be “coming soon.”)

The newspapers describe the system as giving the National Security Agency and the FBI direct access to a huge number of online commercial services, capable of “extracting audio, video, photographs, e-mails, documents, and connection logs that enable analysts to track a person’s movements and contacts over time.”

Since the news broke, Apple, Google, and Facebook have all gone on the record. Apple told CNBC that it never heard of PRISM and did not grant the government such access and echoed the same sentiment to the Wall Street Journal. Facebook told The Next Web that it also does not provide federal authorities with direct access to its servers, and Google told the site that it ”does not have a ‘back door’ for the government to access private user data.” It continued in a statement, "Google cares deeply about the security of our users’ data. We disclose user data to government in accordance with the law, and we review all such requests carefully."

Ars has reached out to Apple, Yahoo, and Paltalk over e-mail for comment but did not hear back at the time of publication. A Google spokesperson—when asked if the company had heard of or participated in the PRISM program—responded with the same statement given to The Next Web.

"We’ve seen reports that Dropbox might be asked to participate in a government program called PRISM," a Dropbox spokesperson told Ars. "We are not part of any such program and remain committed to protecting our users’ privacy."

"Protecting the privacy of our users and their data is a top priority for Facebook. We do not provide any government organization with direct access to Facebook servers," Facebook wrote to Ars. "When Facebook is asked for data or information about specific individuals, we carefully scrutinize any such request for compliance with all applicable laws, and provide information only to the extent required by law."

"We provide customer data only when we receive a legally binding order or subpoena to do so, and never on a voluntary basis," a Microsoft spokesperson responded. "In addition we only ever comply with orders for requests about specific accounts or identifiers. If the government has a broader voluntary national security program to gather customer data we don’t participate in it."

"We do not have any knowledge of the Prism program. We do not disclose user information to government agencies without a court order, subpoena or formal legal process, nor do we provide any government agency with access to our servers," AOL said in a statement Friday.

Kurt Opsahl, a staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, says that these denials may not be very significant.

"Whether they know the code name PRISM, they probably don't," he told Ars. "[Code names are] not routinely shared outside the agency. Saying they've never heard of PRISM doesn't mean much. Generally what we've seen when there have been revelations is something like: 'we can't comment on matters of national security.' The tech companies' responses are unusual in that they're not saying 'we can't comment.' They're designed to give the impression that they're not participating in this."

Over five years of data

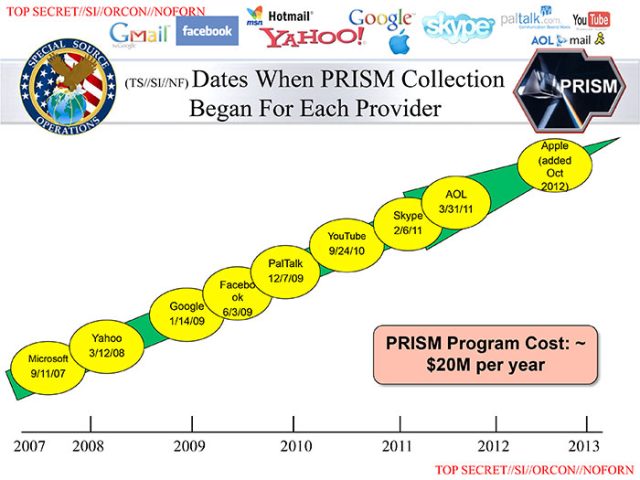

According to The Washington Post and The Guardian, PRISM began with Microsoft being the first company to cooperate with the government’s secret digital dragnet—on September 11, 2007. Apple is alleged to be the most recent collaborator, beginning in October 2012. The reports state that companies are given immunity from federal prosecution in exchange for opening access to their servers to the FBI’s Data Intercept Technology Unit.

The FBI did not immediately respond to Ars’ request for comment. The Post said that government officials “declined to comment for this story.”

As the Post describes the program:

From inside a company’s data stream the NSA is capable of pulling out anything it likes, but under current rules the agency does not try to collect it all.

Analysts who use the system from a Web portal at Fort Meade key in “selectors,” or search terms, that are designed to produce at least 51 percent confidence in a target’s “foreignness.” That is not a very stringent test. Training materials obtained by the Post instruct new analysts to submit accidentally collected US content for a quarterly report, “but it’s nothing to worry about.”

Even when the system works just as advertised, with no American singled out for targeting, the NSA routinely collects a great deal of American content. That is described as “incidental,” and it is inherent in contact chaining, one of the basic tools of the trade. To collect on a suspected spy or foreign terrorist means, at minimum, that everyone in the suspect’s inbox or outbox is swept in. Intelligence analysts are typically taught to chain through contacts two “hops” out from their target, which increases “incidental collection” exponentially. The same math explains the aphorism, from the John Guare play, that no one is more than “six degrees of separation” from Kevin Bacon.

Meanwhile, The Guardian quoted from other slides that have yet to be published.

The presentation ... noted that the US has a "home field advantage" due to housing much of the Internet's architecture. But the presentation claimed "FISA [Forgeign Intelligence Surveillance Act] constraints restricted our 'home field advantage'" because FISA required individual warrants and confirmations that both the sender and receiver of a communication were outside the US.

"FISA was broken because it provided privacy protections to people who were not entitled to them," the presentation claimed. "It took a FISA Court order to collect on foreigners overseas who were communicating with other foreigners overseas simply because the Government was collecting off a wire in the United States. There were too many e-mail accounts to be practical to seek FISAs for all."

The new measures introduced in the FAA redefine "electronic surveillance" to exclude anyone "reasonably believed" to be outside the US—a technical change which reduces the bar to initiating surveillance.

The British newspaper also mentioned that the government “boasts” of a rapid increase in the use of PRISM to obtain communications, noting that requests for Skype capture rose by 248 percent in 2012, 131 percent for Facebook, and 63 percent for Google. When the NSA finds something that it believes is worth investigating further, it issues a “report." “According to the NSA, ‘over 2,000 PRISM-based reports’ are now issued every month. There were 24,005 in 2012, a 27 percent increase on the previous year.”

The Post describes the source who sent the slides as a "career intelligence officer" who had firsthand experience with PRISM and expressed "horror" at what it could do. "They quite literally can watch your ideas form as you type," the officer said.

Update: James Clapper, the Director of National Intelligence released a statement on the program, saying that it did not try to target US citizens: "The Guardian and Washington Post articles refer to collection of communications pursuant to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. This law does not allow the targeting of any U.S. citizen or of any person located within the United States,” the statement said. “The program is subject to oversight by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, the Executive Branch, and Congress. It involves extensive procedures, specifically approved by the court, to ensure that only non-U.S. persons outside the U.S. are targeted, and that minimize the acquisition, retention and dissemination of incidentally acquired information about U.S. persons."

A New York Times source also confirmed the existence of PRISM, but downplayed its effects on Americans, saying that "it minimizes the collection and retention of information 'incidentally acquired' about Americans and permanent residents."

reader comments

338