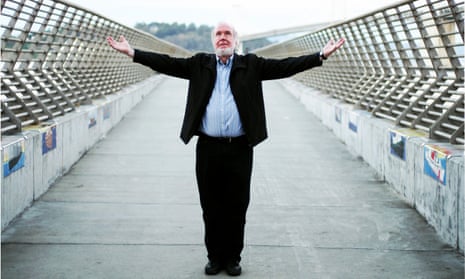

Kevin Kelly may not be a household name but he is one of the quietly influential people who have helped shape the modern world, or at least the bit of it at the end of our keyboards and phones: the internet. A college dropout and a hippy, he spent his 20s and early 30s travelling before landing a job editing the Whole Earth Review, the successor to the Whole Earth Catalog, the counterculture’s “bible” that influenced many computing pioneers. He later became involved in The Well, one of the earliest online forums and virtual communities, and went on co-found Wired magazine. These days, aged 63, he still contributes to Wired (he has the title of “senior maverick”) and also writes books about the future, the latest of which is The Inevitable.

Am I right in thinking that you’re saying the future isn’t as scary as we think, and that it’s coming whether we like it or not so we might as well get used to it?

I think that’s a well-put subtext. The future is going to be a little better than today and we should embrace it so we have a better chance of domesticating it, so to speak. It is only by engaging with technology that we can maximise the benefits and minimise the harms. If we try to prohibit it, outlaw it, stop it, diminish it, we’ll fail. These larger shapes of technology are inevitable.

But while you’re saying we shouldn’t be scared of the future, you also talk about some scary new things coming…

Absolutely. I’m not a utopian. I think technology generates as many new problems as new solutions. And most of the problems we will have in the future are going to be caused by the technologies that we are making today. There are a lot of downsides to them. But if we tally them up, there is a small differential. Basically, we create 2% more a year than we destroy. And, compounded annually over years, that’s what civilisation is. Most people would prefer to live today than 30 years ago, or 50 years ago, or 100 years ago. That’s because we have a few more additional choices, options and opportunities, a few more people in the world are able to reach for their dreams and that small progress, I think, is what should give us optimism for the future.

You live in San Francisco’s Bay Area…

Yeah, I have totally drunk the Kool-Aid.

That was exactly what I was going to ask.

Yes, I am bathed in this American Silicon Valley worldview where the solution to any problem is more technology.

But you make a clear point of saying: “I’m not a utopian”, drawing a distinction between yourself and the so-called techno utopians of Silicon Valley?

Right, though I’ve never actually met one. The techno utopian, I think, is a straw man. Elon Musk is worried about AI and other things. Of course he is also funding AI, right? I think most of us are “protopian”, this is my term for people who believe in progress, who don’t believe there is any kind of a state where we have things solved, but we believe that things are getting a little better and maybe it’s not by much, but that tiny difference is what has built civilisation.

But if we say “technology is inevitable”, does that absolve us of the responsibility of regulating it and overseeing it?

Not at all, because while some forms of technology are inevitable, the specifics aren’t. So, while the internet was inevitable as soon as the planet discovered electricity and wires and stuff, Twitter was not. The internet was inevitable, but the kind of internet was not, whether it was international, national, open or closed, commercial or non-commercial. Those are all choices that we have.

So, it’s 2050 and I’m walking down the street. What’s going on? Do I have a chip in my head? Are there cars flying overhead? Do our cities look different?

I think there will be a small layer of change on top of these immense infrastructures of cities but we’re not going to have flying cars, we’re not going to have jetpacks, but there will be auto-driven cars. But the Industrial Revolution, which did the rearrangement of the physical world, is over. The second Industrial Revolution is about how we use our time, how we identify ourselves and that social aspect. By 2050, we’ll have very well developed virtual realities. There’ll be different ways to share presence and experiences with one another. We’re social animals and that’s what robots don’t do very well right now. At the moment, the internet is the internet of information. With virtual reality and AI, what we’re going to get is an era of experiences, where we can not just know something, but feel it.

When you say that, it just makes me think there’s going to be a lot of porn.

There already is. This is what I’m saying – 49% of what’s made will be crap. We’re creating more and more, this is the interesting thing, if you track the number of songs being written every year, there are millions and millions. We’re on a curve where basically everybody in the world will have written a book or a song or made a video, on average. Most of this is going to have a very small audience but that’s fine. Who cares? I think it’s OK that most of it is crap.

One thing that scares a lot of people about the future is how we’re going to be earning a living. You’ve said that the advertising industry is ripe for the next big disruption. Can you explain this?

In this world with bots and automation, technology basically makes things cheaper and cheaper – only a few things are becoming more expensive. One of those is access to human experiences, concert tickets, Broadway plays, babysitters, all these. The only scarcity that we have in this world is human attention. The disruption is going to come when we start to charge for our attention. Someone will have to pay me to watch their ad, to read their email. People will be paid different amounts, depending on their influence, their connections, their spending. That is where it is going and that takes out the advertising industry as it exists today. There will still be ads; in fact, I think most of those ads are going to be generated by consumers themselves, by the customers.

Isn’t that more or less what’s already happening with Instagram?

Exactly. And it will happen in a much more systematic way.

You were involved in The Well, which was one of the first online communities. Last time I spoke to you, you said you wished that you’d enforced real name usage.

Yes. I think anonymity is like a rare earth element that is required in extremely small doses and is very toxic in anything larger than a minuscule dose. My experience with any kind of community is that they’re stronger, better, more positive to society when they’re not anonymous. We tried to encourage responsibility. We told people they owned their words. But we didn’t emphasise that you were also responsible for them. That’s what I regret.

If you had, do you think the internet would be a different place today?

Absolutely. Online communities were inevitable, but the character of that online community was not at all inevitable. You have a lot of choice and say in them and that makes a huge difference.

You were a futurist adviser on Minority Report. Do you think that’s an accurate depiction of what’s coming down the line?

Our job was to create this everyday world of 2050. I’ve learned a lot from Spielberg in that process because he wasn’t interested in the big trends – he wanted to know what people had for breakfast. I think the world we invented was pretty plausible. Most of it is the same as today, but there’s this overlay of differences. The old persists. We have concrete plumbing, pipes, roads, doorways, glass windows, that’s going to be the majority of what we’ll have in 2050.

How much technology have you actually adopted? Are you on Snapchat? Do you own an Apple watch?

Nope and nope. My job is to try all these things but I’m a minimalist. My first smartphone was an iPhone 6. I didn’t use Twitter until last year. We still don’t have TV at our house. I think this idea of judiciously curating the technologies in your life will be what we do in the future as these choices proliferate.

Finally, if you were 20 now, but knowing what you know now, what would you advise you to do?

Do something that is of service to others. And travel. I think it’s the best thing to confront otherness and get over this disease of nationalism that is a terrible, terrible disease. I think it’s an essential experience for the young. I’m a little sceptical about all these people in their 20s trying to make a lot of money with some new startup – I think it’s not that useful. Better to try something crazy and impossible like trying to go to Mars or something. I think that’s what I’d try and do if I was 20.

The Inevitable by Kevin Kelly is published by Random House USA (£22.50). Click here to order a copy for £18

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion