25 April: C14 attacks and sets alight a Roma camp in Kyiv. Source: Instagram.

The recent wave of anti-Roma pogroms in Ukraine has spawned a new series of texts on right-wing violence. However, a significant part of this literature still mostly relies on discourse analysis, which cannot fully explain the actions of far right organisations on the ground. Analysing far-right movements’ programmes and ideological statements can be useful when combined with a closer look at the actual activities of the movements in question, the way they interact among themselves and the wider social and political context. But judging a group primarily by how it presents itself to the world is misleading.

The lack of primary sources from Ukraine’s far-right milieu, as well as the general scarcity of research on non-EU (and non-Russian) eastern Europe, has led to an exoticised perception of central and eastern Europe as whole – and one that is open to politicisation by both liberals and leftists. Public discussion thus tends to degenerate into either liberal denial of the very existence of the far-right problem in Ukraine or sensationalist and exaggerated “anti-imperialist” accounts of the “fascist junta” ruling the country.

To avoid oversimplification, I focus on the grounded context rather than ideologies and programmes of far-right groups. Here, I will try to contribute to a better understanding of the far right in Ukraine by conceptualising them as “entrepreneurs of political violence” – a portmanteau of two established terms from different fields. A “political entrepreneur” is a political actor who pursues opportunistic strategies aimed at gaining popularity and influence, rather than following a specific ideological agenda. Likewise, “Violent entrepreneurs” is the title of an influential study of Russian organised crime by sociologist Vadim Volkov, who analysed post-Soviet mafia as a particular kind of entrepreneurship where violence resources become a crucially important capital asset.

By taking a similarly pragmatic look at the activities of Ukrainian far right, I claim that they should be viewed as political entrepreneurs who are trying to capitalise on their expertise in violence. This can be a more productive lens than engaged approaches which “take a stance” on the far right – approaches that simply acknowledge the gravity of the situation or belittle it. These tend to be accompanied by wider political conclusions, and do not seek to understand the issue at hand.

I give a concise chronology of the incidents of right-wing violence between January and April 2018 (i.e. before the more recent string of Roma pogroms). I will look only at episodes reported in the media, involving violence or a realistic threat of violence by members of various organised far-right groups, directed outside the far right subculture, in peaceful areas of Ukraine. I will then regroup these episodes, interpreting them as several processes that have their own inner logic, but which intersect in time and space.

Chronology of events

The 2018 season of political violence opened in Kyiv on 19 January, when nationalist organisation C14 attacked a demonstration commemorating Russian antifascists Stanislav Markelov and Anastasia Baburova.

This annual event is a traditional target for the far right, although previous attacks had been led by different forces. C14 activists blocked the demonstration organised by liberal and leftist activists in central Kyiv, shouting down the speakers and attacking them with snowballs and eggs. The Kyiv police failed to create a barrier separating the two demonstrations, advising the antifascists simply “not to provoke” their opponents. Later, the police detained eight anarchists; the arrest was met with cheers from the nationalists, who were free to keep assaulting the demonstrators physically and verbally. After the end of the demonstration, the far right attacked a random passerby whom they mistook for an antifascist – he happened to be a British tourist.

19 January 2018: attack on anti-fascist march, Kyiv. Source: Youtube.

Ten days later, an important incident took place in Lviv. On 28 January, a large group of far-right activists, mostly members of the Azov National Corps and its allied group Misanthropic Division, violently attacked a demonstration (organised by the local leftist scene) against the use of animals in circuses. The attackers threw smoke grenades into the crowd and shook hands with police officers, exchanging the motto “White Pride”. The police soon intervened by detaining leftist demonstrators in a brutal manner; they were all taken to a police station, where they spent several hours.

On the next day, 29 January, Azov’s vigilante organisation National Militia blocked Cherkasy city hall in central Ukraine. Here, they forced city deputies to vote for the self-dissolution of the city council after they refused to approve new members of the executive committee proposed by the mayor. The police did not intervene.

These January events set the trends for the period that followed. On 11 February, Azov fighters violently intervened and stopped a lecture about discrimination in the film industry, held at a cultural centre in Mariupol. On 13 February, a group called Freikorps, which is believed to be close to the Azov/National Corps movement, attacked a lecture on the LGBT movement in Kharkiv in a similar manner. Two days later, C14 and Azov’s National Militia clashed with police forces in Kyiv during a bail court hearing concerning Odessa city mayor Gennady Trukhanov, who is facing theft charges.

International Women’s Day, 8 March, saw many public events and almost as many attacks by far right groups. Azov assaulted feminists and liberals marching in Mariupol. In Kyiv, attackers from several organisations made use of the benevolent passivity of the police, who were reluctant to protect the marchers. A plainclothes police officer actually helped them steal a feminist banner.

The Kyiv police ignored statements by victims of violence. Instead, they opened criminal proceedings against Olena Shevchenko, the organiser of the Women’s March, after nationalists claimed that the contents of the banner were tantamount to desecration of national symbols. The first court hearing was held in the presence of a large nationalist audience, mobilised by C14, Katekhon (a conservative circle tied to Ukrainian far-right political party Svoboda) and Tradition and Order (TiP), a conservative nationalist group. At the second hearing, the defence mobilised their own support, including some diplomats and liberal politicians. With the dignitaries present in the court hall, and with far right waiting outside, the court acquitted Shevchenko. She had to leave by taking a taxi from the court’s backdoor.

On the same day in Lviv, members of National Corps physically assaulted visitors at a feminist exhibition and participants of a “Sisterhood, Support, Solidarity” march. When the marchers retreated into a tram, the attackers started throwing cobblestones at it and later burnt one of their banners saying “No means no”. The city police, meanwhile, stood by, ready to intervene the moment the leftists would try to fight back. Some of the police exchanged friendly greetings with the far right.

Meanwhile, in Uzhgorod, events took a slightly different turn. Activists of the local organisation Karpatska Sich (KS) poured red paint over a speaker at a local feminist demonstration, which led to a chemical eye burn. Here, the police promptly detained the attackers – though they were released later that day. In the week that followed, Karpatska Sich organised a string of attacks against local leftist and liberal activists. Coincidentally, that week also hosted a wave of anonymous property destruction against cars with Hungarian or other EU number plates. Once again, local police reacted very reluctantly. According to activists, these were preparations for a large demonstration that Karpatska Sich staged on 17 March. In Uzhgorod as well as in Lviv, local police, realising their own inability to control the streets during such big events, simply gave carte blanche to the far right.

A 17 March event in Uzhgorod to honour wartime nationalist anti-Hungarian fighters (Karpatska Sich’s namesake) became an event of nationwide importance, gathering a wide spectrum of Ukraine’s extreme right, from Right Sector and Tryzub to C14 and Freikorps. Karpatska Sich, the hosting organisation, accounted for a few dozen of the 250 participants. Contrary to the customary repertoire, the marchers readily demonstrated “controversial” symbols like the “Celtic cross” and gestures like the “Roman salute”. Normally these are avoided at public events as too “provocative”.

17 March: Karpatska Sich hosts a march in honour of wartime anti-Hungarian fighters, Uzhgorod. Source: Karpatska Sich.

On the eve of this gathering, the regional police chief refused to take measures to protect a roundtable on discrimination and hate crimes organised by an LGBT organisation, and strongly advised them to cancel it. Upon receiving this information, the hotel that was to host the event revoked its agreement. Rank-and-file police officers were better disposed to the organisers and helped them leave the town safely.

The town’s leftist/liberal milieu reacted to these events by organising a demonstration “For a European Uzhgorod” on 31 March. Their opponents occupied the same square with their own demonstration,“For traditional family values”. The city council tried to forbid all demonstrations on that day, citing public safety considerations. However, a local court did not prohibit the gatherings. Notably, Karpatska Sich was not officially present at the counter-demonstration: it was formally organised by a KS-allied group “Black Sun”, Social-Nationalist Assembly (SNA) and a few less significant organisations. Karpatska Sich militant activists were present next to the square, but there was no violence on that day. The police did their job, efficiently separating the two demonstrations.

On 19 March, the far right blocked two events organised by liberal NGOs: a roundtable on countering discrimination and hate crimes in Vinnytsia and a lecture on gender-sensitive words in Ivano-Frankivsk. In Vinnytsia, around 40 far right introduced themselves as ordinary citizens, blocking the entrance and demanding to be let inside. The police created a corridor to evacuate the participants of the roundtable. In Ivano-Frankivsk, the lecture was sabotaged by Karpatska Sich and their partner organisation, Sokil. KS promised to repeat such interventions in the future.

On 23 March, a special police squad conducted searches at Kyiv’s ATEK factory, which is used by Azov as its headquarters and training grounds. Police chiefs explained that the intervention had nothing to do with Azov, but the latter nevertheless quickly mobilised around 1,000 supporters, including members of parliament from Svoboda, to block the work of the police and expel them. On that day, Azov leader Andriy Biletsky mentioned that “a considerable part of the military will support in their hearts” a hypothetical coup d’état.

Three days later, 26 March was marked by far-right violence against a lecture about the dangers of the far-right violence in Kyiv: Right Sector, Svoboda and Tradition and Order, altogether around 40 people, invaded a cultural centre and tore down posters bearing the slogan “Respect diversity”. The police pushed them outside, where they verbally attacked people coming in. Two hours later, the police evacuated the building due to an anonymous report of a bomb threat.

On 29 March, several dozen National Militia members broke into the Mykolayiv regional council and demanded that the deputies impeach the regional governor. The deputies did not comply with this request, but the next day the governor himself asked the president Poroshenko for temporary suspension.

On 16 April, an art exhibition dedicated to the far-right violence, which was opened at the premises of a university in Kyiv under heavy police protection, had to close down. The exhibition’s curator insisted on shutting it down, citing the risk of aggression from far-right groups; the administration of the university put additional pressure, accusing the artists of a provocation.

On 18 April, C14 organised an anti-Roma raid at Kyiv railway station. The Roma, who had been staying at the station for a few days, had become the subject of a moral panic in the mainstream Ukrainian media a few days before. On 20 April, Hitler’s birthday, a voluntary “municipal guard” consisting of C14 activists violently expelled a Roma camp from a Kyiv park, burning their possessions in the process. Their report, illustrated with picturesque photos, received a very enthusiastic feedback from the wider public on social media. The city police chief said they had not received any official violence complaints, and that the municipal guard had simply burnt some garbage left by the Roma.

A few days later, when a news website published a video of men chasing Roma families and attacking them with pepper spray and stones, the police said they had opened two criminal proceedings into hate crime and hooliganism.

Connecting the dots

Can this intimidating but chaotic sequence of events be disentangled and regrouped into several distinct plots, each having its own main characters and dynamics even while intersecting with others? I will try to do so below.

The main character of the first thread to be found here, and indeed of the far-right political scene in Ukraine as a whole, is the extended network of various structures known under the general Azov movement brand. Unlike Right Sector, which tried and failed a strategy of violent confrontation with the post-Maidan government, Azov’s leadership has opted for a “long march through the institutions”, extending local patronage networks with criminals and politicians and building a wide network of organisations and side projects.

Azov’s network amounts to a far-right “state within a state” – a universe that aims to monopolise the nationalist sector of Ukraine’s political field

The creation of the Azov Civil Corps was the first step in this direction. This structure, formally divorced from the Azov National Guard regiment, decided on a more pronounced public political face. The Civil Corps served the double purpose of keeping Azov military regiment veterans busy while also spreading Azov’s hegemony among the far-right audience. This was followed by creating the National Corps political party, the network of Azovets children’s summer camps, the Sports Corps, the veterans organisation Zirka, the nation-wide vigilante network of National Militias and other outlets. Azov’s network thus amounts to a far-right “state within a state” – a universe that aims to monopolise the nationalist sector of Ukraine’s political field.

Azov has become an important umbrella brand for Ukrainian far right organisations. Source: Azov.

On the national level, this makes Azov’s political patron, Ukraine’s Interior Minister Arsen Avakov, the second most powerful person in the country, effectively possessing a private army which once in a while makes ambiguous comments about the possibility of a coup. However, the patronage networks and conflicts go much deeper on the local level. Some of them can be uncovered by analysing the events mentioned above.

For instance, the March 2018 incident at the ATEK factory in Kyiv. Here what’s at stake is the struggle for ownership rights to this factory, which currently hosts Azov’s headquarters. The factory previously belonged to Oleksandr Tretiakov, a politician and owner of a Ukrainian lottery operator which allegedly benefits from the National Corps’ violent raids directed against competing lottery outlets under the pretext of a campaign against illegal gambling. Tretiakov’s old political partner, Ukraine’s former justice minister Roman Zvarych, helped Azov establish itself at the factory’s premises in November 2014.

At the time, the factory was at the centre of a corporate conflict. As reported by Hromadske, a former lawyer for one of the parties to the factory dispute, KVV Group, claimed he paid $195,000 to Sergey Korotkikh, Azov’s head of intelligence, to occupy the factory on KVV’s behalf. However, after Azov did this, they refused to permit KVV to enter. Instead, according to KVV's former lawyer, Azov advised KVV to discuss financial matters with Svitlana Zvarych, whose charity foundation demanded 45.5m UAH ($3m) in order for Azov to leave the premises. Svitlana Zvarych refutes this claim. Meanwhile, Azov started converting the factory to produce military equipment with an eye on attracting government orders, while Azov Civil Corps, headed at that time by Roman Zvarych, politicised the conflict by staging street protests “in defense of the factory”.

In October 2016, the co-owner of KVV Group, having spent two months in prison on charges of financing separatism, surrendered his ownership rights to Zvarych’s charitable foundation. However, in the same month, according to Svitlana Zvarych, she was kicked out of the factory by Azov’s forces after refusing to give a share in the company’s capital to Sergey Korotkikh and Vadym Troyan, Kyiv regional police chief and former Azov battalion commander.

This context allows us to better understand Azov’s apparent overreaction to the police visit in March 2018 in contrast to their official explanation, which stated that the “”unreformed” police wanted to plant weapons at Azov’s base and then disband them. Indeed, Azov’s official version helps them mute their ties with Avakov, posing for the nationalist audience as victims of the regime.

Many of Azov’s public gestures, including incidents involving violence, are aimed at reinforcing the image of an independent movement, opposed to both Ukraine’s police leadership and corrupt elites. Azov’s clash with Odessa mayor Gennady Trukhanov’s hired thugs and, more importantly, with the police, is one such publicity stunt which “cleanses” the image of National Squads from allegations of Avakov’s patronage.

Azov’s involvement in the incidents in Cherkasy and Mykolayiv, on the other hand, seems to be connected with its involvement in patronage networks. Cherkasy city council was torn by a conflict between city mayor Anatoliy Bondarenko and city council secretary Oleksandr Radytsky. The latter, supported by the president’s Petro Poroshenko Bloc and the nationalist Svoboda party, commanded the majority of votes in the assembly and paralysed the budget confirmation process. The mayor asked the parliament to dissolve the city council and call a new election.

29 January: the National Militia block Cherkassy city hall. Source: Youtube.

Here, the sudden intervention of Azov’s National Militia, sporting balaclavas and firearms cases, turned the tide in the mayor’s favour. The city council passed the budget and then voted for its own dissolution. Whether or not the claims about Avakov’s political interests in Cherkasy are true, this episode shows that the local configuration of power is often more important than broad political agreements on the national level. Azov played into the hands of the forces belonging to a different camp on the national scale, against fellow nationalists and formal partners from Svoboda.

In Mykolayiv, the official reason for the intervention of Azov’s National Militia were accusations against regional governor Oleksiy Savchenko, whose corrupt ways allegedly motivated the suicide of the local airport director, a war veteran. However, according to another interpretation, this is an episode of a wider conflict between Azov’s patron Arsen Avakov and Ukraine’s former general attorney, police general Vitaliy Yarema. The latter is gaining influence on president Poroshenko, putting his trusted men, former policemen, to important positions in the regions – and Oleksiy Savchenko is one of Yarema’s protégés. For Avakov, who wants to monopolise influence on the Ukrainian police force, this situation is perceived as a threat.

Finally, the Mariupol episodes demonstrate the behaviour of Azov in their “base” city close to the front line. As any large industrial city, Mariupol has a lot of powerful local and regional interests, such as the important metallurgical assets belonging to the country’s richest man, Rinat Akhmetov — these would normally dwarf the influence of the likes of Azov. But the war, given the city’s strategic importance and reasonable doubts about the political loyalty of its population, has made Azov a more influential player.

Mariupol’s Azov movement feel enough at home to have installed a statue of medieval prince Sviatoslav (a central figure in post-Soviet anti-Semitic mythology) in the city centre, despite the lack of official permission from the city council, and to organise regular torchlight marches there. A soldier from Azov, who killed a man in the street after a political argument earlier this year, was released by the local court, which sentenced him to a fine. Even if they do not possess a complete monopoly on violence, Azov has certainly established political control of the streets in Mariupol. To maintain this control, they have to react violently, even if not officially, to any public event which diverges sufficiently from their political agenda.

The struggle for hegemony in Lviv

The contested hegemony over street-level political activism is the common rationale behind the acts of far-right political violence in Lviv. This western city, Ukraine’s “national Piedmont”, has always been considered the heartland of Ukrainian nationalism.

As early as 2010, Svoboda gained an absolute majority in the city council and relative majority in the regional council. At that point, the party was in the control of an energetic militant movement, Autonomous Resistance (AO). Founded by the former Hitlerist leadership of the now defunct Ukrainian National Labour Party, it was headed by Svoboda deputy Yuriy Mykhalchyshyn, whose PhD thesis dealt with the history of NSDAP and Mussolini’s PNF. The militant movement, which followed Strasserism, borrowed its political style from the German autonomists. After a bitter conflict with Mykhalchyshyn in 2013, Autonomous Resistance cut ties with Svoboda and gradually slided leftward politically. It played a prominent role during Maidan in Lviv, occupying the regional council and fighting Svoboda deputies. Coming from a right-wing background, AO paid attention to the development of combat skills of its membership. It created its own MMA training facility, which is the core of a social centre that hosts lectures and presentations. An online shop selling imported athletic clothing previously provided the organisation with an independent source of income.

The peculiar political face of AO – their eclectic left nationalist ideology, commitment to key nationalist symbols and figures, and active participation in the military conflict in the east – has allowed them to survive politically, unlike most other leftist organisations which have failed to find a winning strategy in the post-Maidan environment. A number of splits gave birth to several other organisations, less nationalist but very active, possessing street violence skills and maintaining partnerships with AO. This meant that the street politics of the most important city in western Ukraine was dominated by a leftist milieu.

The first far-right organisation that attempted to contest this situation was Right Sector. In 2015, its local cell forcibly blocked the 1 May “Social march” organised by AO, in order to “prevent a neo-Bolshevik revanche”. However, after a series of splits, Right Sector lost its mobilising potential, as did Svoboda. Over 2016-2017, Lviv has seen a string of dramatic incidents of right-wing violence: a mobilisation against a Festival of Equality which intended to tackle LGBT rights issues; a brutal attack on an AO march by several hundred Nazis; attacks at a Publishers Forum because of two books allegedly promoting LGBT and leftist politics. However, Right Sector did not figure prominently in these incidents. Most of these far-right mobilisations were to a large extent anonymous, featuring “patriotic youth” instead of specific political brands.

The same lack of clear authorship is also true of violent incidents in 2018. However, in personal communication to me, activists who were present on the ground clearly indicate the leading role of Azov’s National Corps in these attacks. According to them, Right Sector today constitutes an alternative to Azov only as a military unit in eastern Ukraine, but politically the latter “has swallowed up both Right Sector and Svoboda”. Most participants of the 2015 blockade have since then either joined National Corps, or military battalions allied to Right Sector or the police force. Having consolidated the local far-right scene, Azov is trying to clean the political field of its leftist competitors. The Lviv police rank-and-file, which is infiltrated by the far right according to local activists, do not prevent, or even choose to help them to achieve this aim.

Why then is the National Corps reluctant to lead the struggle in Lviv as openly as it does elsewhere? Several hypotheses can help answer this question. First, it cannot afford to lose publicly. In November 2016, a potent coalition of several hundred Nazis joined forces to physically destroy the organised left in Lviv – activists arrived from different regions, representing Azov’s Civic Corps, Right Sector and Karpatska Sich. Amazingly, they lost: failing to penetrate the gates of the office under attack, eventually they had to retreat. For political reasons, this kind of loss is unacceptable for an ambitious movement like Azov. Therefore, they will not lead the fight officially unless they are guaranteed to win.

The second hypothesis concerns competition between the agencies of state violence. Both 2016 and 2017 have seen attacks on the Lviv left scene organised by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU). According to persons involved, these investigations seem to have been partially motivated by SBU’s own strategic aims, partially by the request of a local developer, and partially by the personal revenge of Yuri Mykhalchyshyn (who now works for the SBU as a consultant). Whatever the exact reasons in each specific case, Azov’s National Corps would hardly consider it expedient to be seen voluntarily helping the state institution which is traditionally hostile to their political patron Arsen Avakov – and to give other far right groups even more grounds to talk about their subservience to “the regime”.

Finally, Azov’s hegemony over the local extreme right may still not be quite consolidated yet. Their relations with Svoboda may be too complicated for open involvement in Lviv at a scale similar to other cities which have less competitive far-right scenes.

Challengers in Kyiv

In Kyiv, open struggle against the (weaker) leftists and liberals is the preferred activity of C14 – an organisation headed by Yevgen Karas, a former Svoboda activist who split from the party to become an independent entrepreneur of political violence. Compared to the other far right organisations mentioned above, C14’s profile has less to do with quietly establishing informal domination and engaging in illicit activities for material gain, and more with mediatised activities oriented at a wider audience.

Aiming for Ukraine’s mainstream patriotic public, C14 positions itself as a group of young and resolute men ready to employ violence for the sake of (national) justice. Their enemies are usually represented as (latent) supporters of pro-Russian separatists, which automatically diminishes their worth in the eyes of the public and amplifies the attackers’ heroism. In effect, C14 is trying to take the niche that was occupied by Svoboda before Maidan: relatable and well-meaning troublemakers prepared to break the law for the greater good (by comparison, the agenda of National Corps stresses the values of order).

This orientation is obvious from a Facebook poll in which C14 asked their audience which politician associated with the old regime they would like the group to beat up (so far they did not manage to target any of the persons mentioned in the poll). In line with this strategy, Karas freely admitted to a sympathetic journalist that he cooperates with Ukraine’s security services. Among Ukrainian far-right organisations, the activities of C14 are closest to those of Russian online vigilante movements such as “Occupy Pedophily” or “Lev Protiv”; their YouTube channel is consciously crafted to attract audiences (thus literally monetising their violence), and the most popular videos have between 50,000 and 300,000 views.

The recent wave of anti-Roma pogroms fits this strategy very well: it has produced immense positive feedback in the form of online comments from non-politicised “regular citizens”, enhancing brand recognition for C14. Roma can hardly pass as “separatists”, but their marginalised status makes them a perfect aim for this kind of strategically calculated violence. Notably, the first anti-Roma raid at Kyiv railway station was a reaction to swelling public demand (heated up by a moral panic in the media), rather than C14’s own ideologically dictated initiative. Meanwhile, the attack on the Kyiv antifascist rally in January 2018 is the continuation of C14’s more traditional political style – attacking easy targets that can be represented as the “fifth column”.

The 2018 feminist march in Kyiv also proves the selective approach of C14: it did not figure prominently among the counter-protesters on 8 March, but afterwards it seized the opportunity to inflate the hysteria around the feminist banner, claiming that the symbol of Azov’s National Militia on it looked too much like Ukraine’s national symbol, and was located too close to the woman’s anus. Characteristically, the National Militia ignored the story, but C14 did its best to mobilise its activists to attend the court hearings.

Here, though, there is a deeper calculation: consolidating Kyiv’s far-right scene behind C14. Just like Azov, C14 combine generic “healthy patriotic” message with subtler hints which can be easily deciphered by members of the subculture (such as the symbolic date of the Roma pogrom on Hitler’s birthday or indeed the very name of the organisation). Similarly, people belonging to politicised subcultures understand very well that the antifascists who were attacked in January 2018 were not Kremlin agents, but old political enemies who cannot be allowed to grow stronger. Having created a “municipal guard” officially financed by Kyiv’s city council, C14 works towards realising both aims: it gives them a pretext to patrol streets and maximise the probability of violent encounters (which can be publicised), and at the same time provides a “second-best” opportunity to those who could or would not join the structures of Azov.

The desire to dominate the local far-right milieu is also apparent behind another series of violent acts by C14, not mentioned above because they were directed against the participants of the far-right scene. Dmitry Riznichenko, a prominent veteran of Ukraine’s far right scene and former member of C14, left the organisation after Maidan. After serving in the Donbas volunteer battalion, Riznichenko created his own organisation, more socially liberal than is custom among today’s far right. (Some have gone as far as declaring him a leftist.) Whatever Riznichenko’s actual political views, the important thing is that he, along with another “erring rightist” organisation ChorKom (Black Committee), maintains openly friendly relations with Lviv’s AO and openly challenges the hierarchy within the scene. Struggling to defend its authority, C14 launched an intensive campaign of brutal physical attacks against Riznichenko.

“Anti-gender” ideology as a universal mobiliser

Even though neither Azov nor C14 explicitly mobilised for International Women’s Day on 8 March, the demonstration did encounter violent far-right counter-protesters, aided and abetted by some rank-and-file policemen belonging to the same political milieu.

The most prominent violent proponent of the “anti-gender” agenda in the post-Maidan years has been Right Sector. Its ideological face was always more “fascist” or “Francoist” than the white supremacist/Hitlerist Azov or LePen-like Svoboda. Inside the movement, Right Sector was the main engine behind violent mobilisations against LGBT events such as the Equality March in Kyiv. On the wider scale, it contributed to popularising and reinforcing the dichotomy between pro-EU, pro-Poroshenko liberals and revolutionary conservative nationalists.

Today, this dichotomy is a common-sense understanding. The “anti-gender” ideology has turned from an exclusive feature of Right Sector into a generic far-right set of ideas, which can be used by anyone. This is one reason behind the anonymity of some attacks and blockages: their authorship is known inside the relevant milieu, serving as one of the criteria for building subculture hierarchies.

It is also noticeable that Azov has never officially participated in any “gendered” violent actions. Even in their “home” town of Mariupol, attacks are not formally done on behalf of the movement. Partially, this can be explained by their special relationship with the state leadership, which was dying to hide all visible manifestations of xenophobia, homophobia and other signs of lack of social progress from the eyes of the EU, which could have reacted by backtracking on the visa-free regime, politically important for Ukrainian government.

However, this type of violence also generally does not fit Azov’s strategy of publicity. They like repeating that they fight “real and strong” enemies – Russians and separatists, but also corrupt officials and other powerful figures within the society, almost ignoring some classic rightist scapegoats.

Instead, the “anti-gender” violence scene has recently seen the rise of two new aspiring actors, which stand behind all recent “gendered” episodes in Kyiv. One of them, Katekhon, is a conservative Orthodox group, somewhat resembling the Russian Union of Orthodox Banner-Bearers with their aggressive fundamentalist style. This group is headed by Yuriy Noyevyi, a politician from Svoboda. Not long ago, in 2012-2014, Noyevyi and his comrades were active in a different niche: their organisation Ukrainian Student attempted to become a far-right student union, competing for the influence with the anarcho-syndicalist union Priama Diya (Direct Action). When the latter ceased to be an important political contender, Noyevyi’s interests shifted from university syndicalism to religious fundamentalism. Effectively, Katekhon is the rebranded Ukrainian Student, serving the same technological purposes – promoting the interests of the party in the spheres which are considered the most promising at the moment.

The second ambitious newcomer at the market of gendered political violence is Tradition and Order (TiP). This party was created in the second half of 2016, and took Revanche, a group of admirers of Italian fascism, as its basis. The creation of the party was facilitated by political technologists involved in the patronage circles of the president’s political party, Petro Poroshenko Bloc. Today, the perception of TiP as “pro-Poroshenko” is widely shared in Kyiv’s marginal political subculture. Most likely, their task is to try and create an alternative centre of gravity among the far right that would balance the influence of Azov (whose political patron is not unconditionally loyal to Poroshenko) and the remaining authority of Svoboda and Right Sector.

Thus, people violently fighting against “gender propaganda” shoulder to shoulder were brought together in the same place by very different, and sometimes mutually exclusive, considerations. In March 2017, National Corps, Svoboda and Right Sector signed a “National Manifesto”, pledging to coordinate their efforts in a joint struggle against the government; however, in reality this political field is full of conflicting interests as well as ambitious newcomers with powerful patrons.

The regional monopoly in Uzhgorod

There is one more far right group actively and violently fighting against “gender ideology” in Ukraine – Karpatska Sich (KS), whose area of activity is mostly confined to Uzhgorod. Unlike Azov, they are not tied by the limitations imposed by high-status patrons and parliamentary political ambitions, and do not shy away from certain topics, catering to all possible audiences in the regional far-right milieu.

This group is a financially self-sufficient political and criminal unit, functioning in a border region where smuggling and similar petty criminal activities are an important source of income for a large part of the population. The leadership of KS are founders of a charitable foundation that receives goods confiscated at the customs for free, pledging to deliver them to soldiers at the eastern front. However, among the goods thus obtained there were two tonnes of marble and women’s lingerie, which can be hardly considered a useful material aid but can be profitably sold. One of the founders also figures in cases of illicit land allocations by Uzhgorod city council.

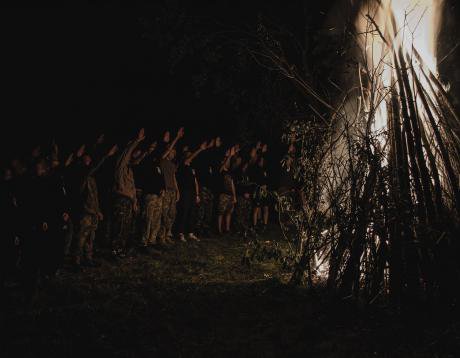

Members of Karpatska Sich perform a "traditional" greeting in front of a fire, August 2018. Source: Facebook.

Simultaneously, KS has successfully established its exclusive control over street-level violence in Uzhgorod. The publication of the information on their illicit activities by a local anti-corruption activist was followed by a string of attacks against him and his colleagues by KS. On the other hand, the nature of their relations with the police and local government is markedly different from the situation in Kyiv and Lviv. In this case, there is hardly an infiltration or benevolent attitude on the part of rank-and-file policemen; rather, the police and the state apparatus are too weak to persecute KS as severely as they perhaps would like to. In 2017, the leader of KS Taras Deyak was included in the list of 100 most influential people of the region – this is very unusual, and suggests the depth of the group’s involvement in local criminal networks.

This influence is used to expand the clout of KS among the far-right scene and reap benefits in high politics. The list of organisations which participated in the 79th anniversary march was telling. It did not include either National Corps or Svoboda. Instead, it featured C14 (whose sphere of influence is geographically divided from KS) and the Social-National Assembly. According to some rumours, the leader of SNA Oleh Odnorozhenko (who was previously Azov’s main ideologue) is drifting closer to Oleh Lyashko and Igor Mosiychuk – people who left Azov in 2014. Lyashko’s Radical Party is an influential player in mainstream politics, and he personally enjoys high rankings in presidential polls, opposing both Avakov and Poroshenko. Odnorozhenko’s frequent visits to Uzhgorod and participation in joint events may be a prelude to the inclusion of SNA and KS into Lyashko’s electoral machine.

Hegemony toolkit: Dosing violence, choosing friends and victims

The first and most important of the plots we have been able to discern above is the establishment of the Azov movement as dominant in Ukraine’s far-right scene on the national level – and as a significant political player in the mainstream political scene.

The key factors that have allowed Azov to rise to these positions are its strategic choices to maintain a reserved but not hostile public attitude towards the government and to maintain close patron-client relationships with certain factions both on the national level and in specific regional and local configurations. The third factor is Azov’s military background, which grants it access to the infrastructure of violence (arms, training facilities etc.) and ensures its legitimacy both in the eyes of the wider public and of the nationalist scene. This legitimacy hinges on the balanced demonstration of the resources of violence available to the movement and its discretion in using them.

This combination is unique among the major far-right structures in Ukraine. Right Sector has a strong military component, but its decision to choose an openly confrontational path in its relations with the governing factions of the ruling class has prevented it from gaining access to important physical and symbolic resources. In this situation, Right Sector’s bet on their clientelist relations with an opposition faction of Ukraine’s haute bourgeoisie (Ihor Kolomoisky’s Privat Group) and revolutionary image did not pay off. Now this movement seems to be in decline.

Svoboda, meanwhile, was too compromised by its perceived proximity to power during and immediately after Maidan. The creation of Svoboda’s own volunteer war units appears to have failed to neutralise the lack of radicalism and militarism in its public image. Its advertised readiness to resort to violence was the key to Svoboda’s electoral success before Maidan, but this was overshadowed by the efforts of the competing entrepreneurs of political violence in the post-Maidan conjuncture, in which the level of and tolerance to violence has escalated. On the other hand, Svoboda keeps holding on to its hegemony in regional power settings in western Ukraine, even though its relations to nation-wide patronage networks is unclear. All in all, Azov/National Corps seems to be clearly the most successful partner in the big nationalist threesome, receiving the most from this alliance.

As mentioned above, Azov’s success hinges partly on the measured dosage of violence in the public space, which should project an image of a force conscious of its superiority in terms of violent resources – but still using it sparingly. This is why National Corps prefers semi-anonymity when acting in situations where its single-handed superiority is not guaranteed a priori, like in Kyiv and Lviv. Its interpenetration with the police forces helps it establish its hegemony in a covert manner. The efforts of National Corps to dominate street politics in Lviv are the second plot.

The third plot concerns the activities of C14 in Kyiv. This movement is closer to a classic vigilante group, generously using violence against commonly recognised “public enemies”, i.e. subjects of moral panic like the Roma or alleged pro-Russian fifth columnist. In their activity, they appeal to two audiences: the wider public with its patriotic and anti-Roma instincts and the far-right political subculture able to see more nuanced details. The first dimension makes C14 a structural analogue of Russian vigilante groups with their commercialised online platforms; the second dimension, oriented inside the far-right scene, has elevated C14 to the position of a co-organiser of the annual nationalist marches on 14 October, on a par with the much more powerful Azov, Svoboda and Right Sector.

The use of “anti-gender” ideology is the fourth theme. The cases analysed here show that this mobilising subject is used as a self-promotion arena by two competing groups: Katekhon, trying to restore Svoboda’s once leading positions in the scene; and TiP, aimed at creating there a separate gravitation pole embedded in Poroshenko’s patronage network. On the other hand, Azov/National Corps seems reluctant to invest too much effort in forcing the topic.

Finally, a separate plot is unfolding in Uzhgorod, where the locally entrenched political and criminal structure Karpatska Sich is overtly competing with the state apparatus for influence on the regional level and is struggling to build alliances on the national scale. These alliances, if constructed successfully, will be able to undermine the dominance of Azov/National Corps by creating a patronage network of comparable capacity to compete with it politically and otherwise on all levels.

As I have argued above, Ukraine’s far right are taking the logic of “violent entrepreneurship” outside the purely commercial and apolitical realm – and employing it in the domain of political contestation, where illicit violence is a precious resource that can be bought and rented. Ukrainian Nazi movements thus exist on the intersection of several worlds (criminal, commercial, military, marginal-political, mainstream political) and are prepared to mobilise their violent resources for advancement of their own positions, up to and including displacing former patrons and stepping into their shoes. The skillful and measured management and use of these violent resources is the key to success in this strategy.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.