Things are difficult – and not particularly cheerful – at the moment.

The so-called migrant crisis, the barbarism of ISIS troops in Syria and elsewhere, the humanitarian and fiscal crisis of Greece, Europe’s politicians’ utter inability to defend the human(e)ly necessary against nationalist and populist voices as well as against those of the world of finance . . . depressing, shocking, and utterly soul-destroying news everywhere.

Things took a dramatic turn this week due to the power that comes with masterfully arranged images – a medium so much more immediate and full of impact than any text can ever be.

First, there were the images of ISIS felons blowing up the ancient ruins of Palmyra for the sake of it (i. e. to hurt the Westerners in their love for everything ancient as well as to sell everything they can on the antiques market, in order to finance future heinous efforts).

Aylan and Galip Kurdi during happier times. – Image source here [caution: graphic images on the linked webpage].

The photos of Aylan Kurdi’s corpse may well prove to have been a game changer. David Cameron, Britain’s Prime Minister and Supreme Blowhard when it comes to foreign affairs (from Britain’s EU membership to immigration), announced that – against his earlier statements – Britain will now take a share of Syrian refugees after all.

Too late, too little, of course, but then basic principles of compassion and humanity tend to fly out of the window whenever there are elections to be won, nationalist parties to be fought, and that particular brand of narrow-minded, selfish, and paranoid people (you know, those who always think that everyone out there has nothing better to do than to inconvenience them personally and to take away their hard-earned money) to be impressed – against all ethics and the convictions of a vast (if not always necessarily particularly vocal) majority of the British people.

In fact, even Britain’s deeply hypocritical rags and wannabe-representatives of the vox populi, The Sun and the Daily Mail, could no longer sustain their extended anti-immigration campaigns.

The study of history does not teach us much (if, in fact, anything): it never has, and presumably it never will. But every now and then, the study of history provides us with remarkable little stories that put current events into an interesting light and a long-term perspective – and challenge us to reflect a bit about our own behaviour (though, chances are, no one will change their behaviours as a result of it anyway).

The historical presence of Syrians in Britain is one such story, however – and it dates back a lot further than one might at first expect. In fact, it dates back – at least! – to Roman times, when Syrians, as part of the Roman auxiliary forces, helped to establish and to build the province of Britannia.

In the corpus of Roman inscriptions from Britain, there are numerous examples of individuals who self-identify as Syrians by nationality. The single most remarkable instance is attested on a lavish (and undoubtedly expensive) memorial that was discovered at Arbeia (South Shields), by the Eastern end of Hadrian’s wall:

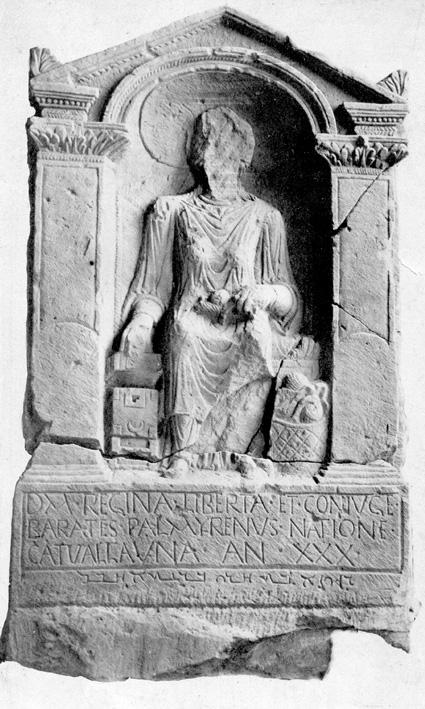

RIB 1065. – Image source here.

The piece – a tombstone for a woman called Regina of uncertain date (possibly second century A. D.?) – consists of three essential components, only two of which may immediately appear to the untrained eye: a sculpture, and two inscriptions (yes, two, not just one).

The ‘main’ (as in: ‘bigger, framed’) inscription is written in Latin and reads as follows (RIB 1065):

D(is) M(anibus). Regina(m) liberta(m) et coniuge(m)

Barat(h)es Palmyrenus natione

Catvallauna(m) an(norum) XXX.

In English:

To the Spirits of the Departed. Barathes of Palmyra (sc. buries here) Regina, a freedwoman and his wife, a Catuvellaunian by origin, aged 30.

Barathes, a Syrian, who self-identifies in this inscription as a native of Palmyra, would appear to be a foreigner (peregrinus) not only to Britain, but to the Roman Empire – and one may well wonder what he and his wife Regina were doing in Roman Britain near Hadrian’s wall.

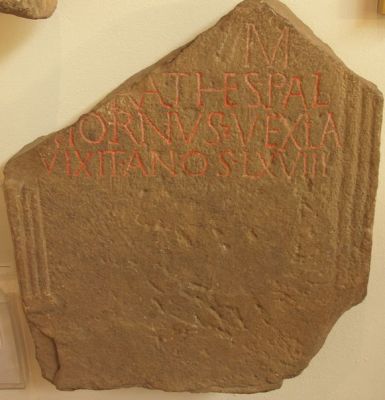

Another inscription from Hadrian’s wall, discovered at the Roman fort of Coria (Corbridge) just over 25 miles away from the above item and substantially less well executed, mentions another citizen of Palmyra. Due to its fragmentation, the stone does not exhibit his name in full – all that survives is the second half of it: [- – -]rathes (RIB 1171):

RIB 1171. – Image source here.

It is tempting (and perfectly plausible) to supplement this as [Ba]rathes. But is this the same man as the Barathes of the inscription above? After all, Barathes is not an altogether uncommon name in Palmyrene nomenclature. But how many of them will have been at Hadrian’s wall at the time…?

If – and that is a big if – the two Baratheses are identical (to be clear: more likely than not, they were NOT identical!), then the second stone reveals the man’s occupation: according to the Corbridge stone he was a vexil(l)a(rius) and died aged 68 (vixit an(n)os LXVIII).

The most obvious understanding of vexil(l)a(rius) is ‘standard-bearer’ or ‘flag-bearer’, i. e. a military position. As suggested before, however, there are very good reasons to assume that neither Barathes (whether or not they were identical) were a Roman citizens, but peregrini instead. In that case, one must wonder if the Barathes of RIB 1171 was a military man at all, or whether vexillarius was a title for either a merchant in flags and other signs (unattested otherwise, but not to be ruled out a priori) or whether he held a ceremonial function in a collegium fabrorum (‘guild of engineers’), for example.

The discrepancy in lavishness between the stone for the wife and for Barathes himself (if identical!) could thus be explained by a decrease in wealth, once Barathes had reached a certain age and could no longer work as a craftsman.

Be that as it may (and once again, the identification of the two, as proposed by some, is tenuous at best). Returning to the stone from South Shields, one must wonder about another detail: Regina, the wife, is described as a native of the Britannic tribe of the Catuvellauni as well as a freedwoman. The Catuvellauni were a Celtic tribe that inhabited an area north of modern-day London, roughly covering modern-day Hertfordshire and stretching as far north as Cambridgeshire.

How did she end up (i) at Hadrian’s wall and (ii) in Barathes’ possession, so that he could act as her patron (though not under Roman but, presumably, under Palmyrene law)?

The first question is impossible to answer. The second question cannot be answered with any certainty, but there are two main options: either she was captured and sold into slavery as a result of a Roman military campaign, or – equally possible – she was sold into slavery by her own family.

It is not clear as to whether Barathes was the ‘first’ owner of Regina as a slave, or whether he acquired her from someone else. As Regina (‘queen’) is a Latin name unlikely to be her native Celtic name (and hardly a Palmyrene name, unlike Barathes’), one must assume that she took this name during her enslavement.

The way in which Barathes chose to have his former slave and then wife represented in the sculpture of her tombstone lives up to the notion of, if not a queen, an eminently dignified, upper-class lady. The editors of the Roman Inscriptions of Britain describe the artwork of the stone as follows:

‘[T]he deceased sits facing front in a wicker chair. She wears a long-sleeved robe over her tunic, which reaches to her feet. Round her neck is a necklace of cable pattern, and on her wrists similar bracelets. On her lap she holds a distaff and spindle, while at her left side is her work-basket with balls of wool. With her right hand she holds open her unlocked jewellery-box. Her head is surrounded by a large nimbus (…)’.

Regina may not have been a queen in real life, but Barathes certainly presents her as almost sitting on a throne – presented in the garments and posture of a lady from Palmyra, dignified, wealthy, leading a distinguished, civilised life up to the time of her (relatively young) demise.

There is another aspect to the memorial, however, that is quite indicative of both Barathes’ attitude towards identity and his relationship with Regina. As mentioned initially, the monument does not only exhibit one (Latin) inscription, but two. Underneath the framed Latin inscription, there is a second one, written in Barathes’ native tongue, Palmyrene, which reads as follows:

רגיןאבתחריברעתאחבל

In English:

Regina, freedwoman of Barathes: alas!

The Latin inscription pays heed to circumstance – an environment in which Latin had become the language of the rulers and in which the couple had learnt to survive (and apparently to do reasonably well – at least to a certain point in Barathes’ life). It operates with official terms such as liberta (‘freedwoman) and coniux (‘wife’) – though they are unlikely to be labels under Roman law (as mentioned before).

In letters rather less awkwardly written than the Latin (leading some scholars to believe that this was carved by an Eastern craftsman rather than a local one), the inscription does not merely repeat the essential information in the widower’s own language – it adds the personal expression of grief, ‘alas!’ to it, visible only to those who pay attention to the ‘fine print’ at the bottom, understandable only to those who know the script and the language, meaningful only to Barathes himself. It is the personal aside of someone who has largely accepted the leading culture for himself, without being prepared to bid farewell to his own identity – that of a foreigner, thousands of miles away from his native Palmyra in Syria.

Barathes, the Syrian in Roman Britain, has done something beautiful. He acquired, freed, and married a girl from Britain, whose life had taken a disastrous turn – becoming a slave, either as a result of Roman campaigns or as a result of her family’s poverty (or greed) in uncertain times. He, as the tombstone suggests, gave her dignity, safety, and made her his queen, not only in name.

Times have changed a lot. Regina’s story is one that, nowadays, happens on a daily basis in Syria, in Palmyra, in the war-torn Near East, under the vicious regime of ISIS fighters and other parties.

Who will save those people from their predicament and restore their well-being and dignity?

Who will be their Barathes?

Beautifully expressed – thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, that is very kind of you to say!

LikeLiked by 1 person

impressive and touching

LikeLike