Story highlights

Thanks to social media, missteps and misinformation get repeated more quickly than ever

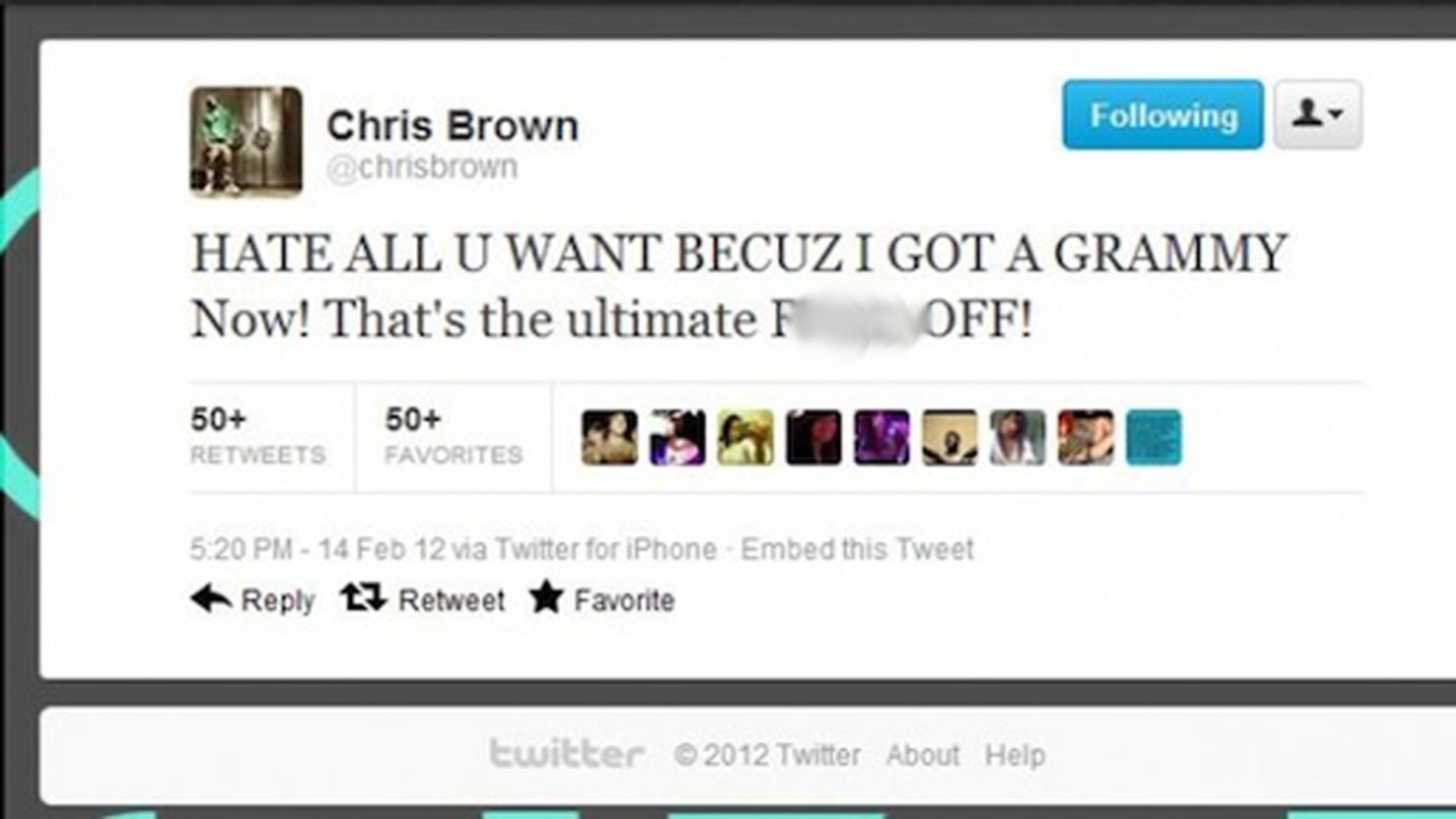

Singer Chris Brown posted profane tweets after the Grammys, then deleted them

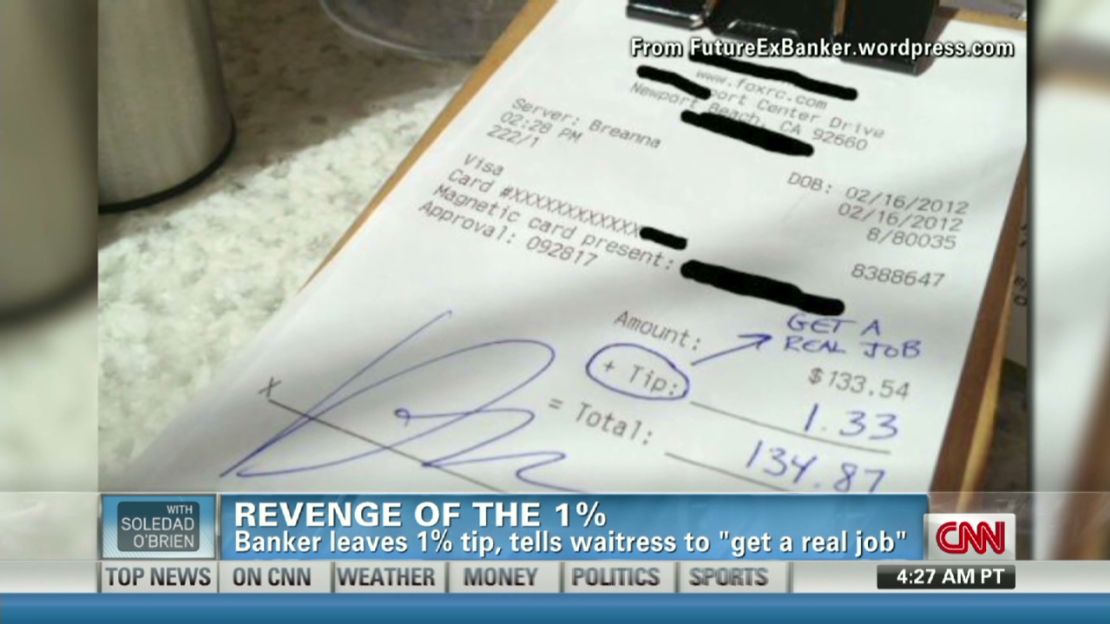

A story about a banker leaving a 1% restaurant tip went viral before it was revealed a hoax

Mistakes online can be fixed quickly, but not before damage is done

You probably heard the story. It is, after all, so last week.

A wealthy banker goes out to lunch with a colleague. The banker disdainfully leaves a 1% tip on a $133 bill with the message, “Get a real job.” The colleague, who runs a blog called “Future Ex-Banker,” takes a picture of the receipt, which then goes viral – first on Eater.com, then on Twitter and Facebook, soon everywhere (including CNN).

It was a hoax, however, though it took a few days before the restaurant found proof the original receipt had been Photoshopped. By that time, despite some disclaimers along the way, the bill had become water-cooler gospel and left outrage in its wake.

So it goes on the Internet, where errors, mistakes and knee-jerk reactions can be let loose at the click of a button.

CNN Photos: Our mobile addiction

Sure, it’s been that way since your grandmother e-mailed you the story about the Nieman-Marcus chocolate-chip cookie recipe.

But in an increasingly connected world where social networking has made us all news sources, that means missteps and misinformation get issued – and repeated – more quickly than ever. Gabrielle Giffords is declared dead, Chris Brown lets fly with profane rants, and it all makes the rounds before anyone has time to think.

“There’s never been such pressure to speak before one knows,” says science writer James Gleick, who traced the increasing speed of society in his book “Faster” and the deluge of data in last year’s “The Information.” There’s always been a desire to gather and disseminate news, he points out, “but never until now has it been global and instantaneous.”

We want information, but more than that, we want it quickly – and thanks to smartphones, which now comprise the majority of cell phones in the United States, we’re never far away from the latest bits of media. Moreover, with cellular companies promoting blazing “4G” speeds and trying to expand their networks, it’s harder and harder to be out of touch – and easier and easier to give in to the twitch of the clicker finger.

And accuracy? Speed rules, baby. Even when your phone attempts to helpfully AutoCorrect a hastily written text, the result is as often mocked as appreciated.

So much for patience. We want the world to listen, and we want it now.

“Everyone now has a global platform on which they can shout their opinions and voice their beliefs,” says Frank Farley, a psychology professor at Temple University and former president of the American Psychological Association. But people haven’t become more cautious about putting words out there, he adds – even if they’re wrong.

“There’s an old economic principle, that bad money drives out good,” he says. “One thing that worries me is that bad information is driving out good.”

Me first!

Of course, the desire to be first, even at the risk of being wrong, is nothing new. But social networks and real-time Internet portability have combined to spawn errors and reactions at an increasingly breakneck pace, particularly on Twitter, which – with its brevity and scope – makes it easy to disseminate clickbacks and comebacks in 140 characters or fewer.

Many errors are minor. Actor LeVar Burton, mistaking Twitter’s private and public spheres, accidentally released his phone number to the entire Twitterverse, then backtracked with a joke. Celebrity rumors roar through all the time, causing quick kerfuffles as they’re checked and then dismissed.

Others, however, are more dramatic. Last month controversial hip-hop singer Chris Brown posted a defiant message after the Grammys – a tweet that didn’t go over well. Soon afterward, Brown (or his handlers) deleted all evidence of his Twitter tantrum, but not before bloggers had grabbed screen shots of the offending missives.

Several news services initially tweeted that Arizona Rep. Gabrielle Giffords had died in the Tucson shootings last year. When Giffords was confirmed to be alive, some deleted their early posts.

Actor Ashton Kutcher, who has close to 10 million Twitter followers, tweeted a protest of Penn State coach Joe Paterno’s firing – before realizing why Paterno was being let go. Kutcher later apologized, deleted his earlier messages and finally put his Twitter account under the control of his publicists.

Wrong or right, speed is exciting, says Gleick.

“The fact is, we love this fast pace. We’re exhilarated by it,” he says. “We’re happy to be able to reach in a pocket and press a button or speak to our device and instantaneously get an answer to a question – even if we know that the answer is not 100% reliable.”

And being first (or, to many Internet commenters, “First!”) is even better: the “primacy effect,” it’s called in psychology. We tend to remember the first items in a series more than later entries.

With speed of the essence, some websites have built a following by trafficking in rumors and uncertainties. In tech, of course, there are any number of sites devoted to all things Apple, which seize on the smallest bits of information, then watch as the unconfirmed reports get picked up by larger tech sites until they go mainstream.

The sociologist Erving Goffman observed that people have “front-stage” and “backstage” presentations of themselves – the former a polished form intended for public consumption, the latter raw and unedited. “I think there’s more and more of the backstage leaking into day-to-day conversation,” says Ron Bishop, a pop culture professor at Drexel University.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing. For corporations such as Apple, an outburst of rumors certainly creates (or maintains) interest. The availability of smartphones encourages citizen journalism. And the ability to post quickly means that misinformation can also be corrected quickly, often after the Twitterverse flags an error.

Truthyness

The flip side, however, plays off Farley’s concern that bad information will drive out good.

“You can do a fast correction, but it hardly ever has the value of the original,” he points out.

Social networks are also useful in spreading propaganda and disinformation, observes Filippo Menczer, a professor of informatics at Indiana University. It’s the latest twist on unwittingly forwarding viruses via e-mail.

Menczer, who directs IU’s Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research, has helped develop Truthy, a system to analyze Twitter posts that he was inspired to set up after the 2010 Massachusetts special senate election. An activist group created several fake Twitter accounts and put out misleading claims about one candidate; thousands of followers retweeted the information. Though Twitter quickly disabled the accounts, the information was spread widely enough to rank highly in Google results.

Truthy attempts to find out who’s responsible for the initial message, how it has been spread and determine if the message is true. There are some tip-offs, Menczer observes, such as if the initial message comes from a now-inactive account or one with a suspicious name. (In the case of the 1% receipt, the “Future Ex-Banker’s” blog was inactive by the time other sites started sniffing around, though it was thought that he was remaining anonymous for less suspicious reasons.)

Americans may associate such disinformation campaigns with domestic politics, but they have also taken root overseas, Menczer adds. As social media has become a key tool in quickly spreading the word about meetings and protests – such as the world saw during the Arab Spring – it can also be used against such efforts. During Russia’s current election campaign, for example, fake accounts posted inaccurate information, making it very difficult for protesters to coordinate through social media, he says.

Given the rush of information on the Web – and that ever-itchy clicker finger – the best strategy may be a little self-control, says Temple’s Farley.

Though, he adds, it’s not easy, particularly with a generation that has come of age with the latest technologies and thinks nothing of not thinking.

“In this world of hyper-stimulation, how do you develop kids who are reflective, who can think before they act?” he says. “That’s going to be extremely important going forward, because there’s so much opportunity for stimulation.”

Better to take a breath, have the facts straight – or risk adding to the flood of error. It’s a truism that certainly predates the Internet.

“A lie can travel halfway ‘round the world while the truth is putting on its shoes,” Mark Twain once said.

Hmm. Or did he?