Abstract

Studies describing the link between infant sleeping arrangements and postpartum maternal depressive symptoms have led to inconsistent findings. However, expectations regarding these sleeping arrangements were rarely taken into consideration. Furthermore, very few studies on pediatric sleep have included fathers. Therefore, the aims of this study were (1) to compare maternal and paternal attitudes regarding co-sleeping arrangements and (2) to explore the associations among sleeping arrangements, the discrepancy between expected and actual sleeping arrangements, and depressive symptoms, in mothers and fathers. General attitudes about co-sleeping, sleeping arrangements and the discrepancy between expected and actual sleeping arrangements were assessed using the Sleep Practices Questionnaire (SPQ) in 92 parents (41 couples and 10 parents who participated alone in the study) of 6-month-old infants. Parental depressive symptoms were measured with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D). Within the same couple, mothers were generally more supportive than fathers of a co-sleeping arrangement (p < 0.01). Multivariate linear mixed model analyses showed that both mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms were significantly associated with a greater discrepancy between the expected and actual sleeping arrangement (small to moderate effect size) (p < 0.05) regardless of the actual sleeping arrangement. These findings shed new light on the conflicting results concerning the link between co-sleeping and parental depressive symptoms reported in the literature. Researchers and clinicians should consider not only actual sleeping arrangements, but also parents’ expectations.

Highlights

Mothers and fathers, from the same couple, may have different attitudes toward co-sleeping arrangements.

Sleeping arrangements themselves are not necessarily associated with depressive symptoms.

A greater discrepancy between expected and actual sleeping arrangement is linked with more depressive symptoms regardless of actual sleep practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Co-sleeping refers to a situation where parents and their infant sleep close to each other, either on the same surface or in the same room, but in two separate beds (Smith et al., 2017). Hence, co-sleeping can be further categorized as bedsharing or room sharing with parents, but not all studies make this differentiation. While any type of co-sleeping can be a reactive practice (families that typically prefer a solitary sleeping arrangement, but who practice co-sleeping in response to their child’s nocturnal behaviors), it can also be intentional/planned (families that usually practice and prefer a co-sleeping arrangement; Keller & Goldberg, 2004; Shimizu & Teti, 2018). In the present article, specific subcategories (bedsharing, room sharing, reactive or intentional) will be used to describe cited studies when possible and the term co-sleeping will be used to identify undetermined or undefined arrangements.

Parents are exposed to conflicting advice around co-sleeping (Mileva-Seitz et al., 2017). Some benefits of co-sleeping include facilitating breastfeeding at night, as well as promoting physical proximity and emotional closeness between the parents and the infant (Barry, 2019). Arguments against the practice of co-sleeping include fear of jeopardizing the intimacy of the parents (Messmer et al., 2012) and concerns related to independence development of the child (Tully et al., 2015). While bedsharing has been more specifically associated with an increased risk of overlays and sudden unexpected infant death syndrome (SUIDS) when practiced on unsafe surfaces or while consuming alcohol or drugs (Blair et al., 2009; Colvin et al., 2014), other authors have reported that bedsharing can actually reduce the risk of SUIDS (McKenna & McDade, 2005; Mileva-Seitz et al., 2017).

In addition to conflicting safety concerns, parents’ decisions regarding infant sleeping arrangement are also influenced by the cultural norms in place. In Western cultures, most infants sleep in a separate room from parents, whereas in non-Western cultures many parents tend to co‐sleep (Barry, 2019). Even though few studies have examined the prevalence of co-sleeping in Western industrialized countries, it appears that its practice is increasing in North America. In a recent national epidemiological study of 1.5 million Canadian mothers, one-third (33%) of participants reported that their infant bed-shared with someone else every day or almost every day, 27% reported occasional bedsharing, and 40% answered that their infant had never shared a bed (Gilmour et al., 2019). In the United States, the proportion of families choosing to room share and bedshare has also been rising consistently over the past several years (Barry, 2021; Colson et al., 2013). Indeed, in a survey conducted in 2018, about half of the sample reported room-sharing with their 6-month-old infant (Volkovich et al., 2018). The increase in co-sleeping prevalence in Western countries supports the importance of understanding how sleep arrangements are linked with parental well-being.

Infant Sleeping Arrangement and Parental Depressive Symptoms

Mothers are particularly vulnerable to developing poor mental health during the postpartum period (Barba-Müller et al., 2019; O’Hara & Wisner, 2014) with onset usually occurring within the first 6 weeks postpartum (Kettunen et al., 2014). Indeed, a systematic review and meta-analysis reports 17% of healthy mothers will experience a depressive episode during the first year postpartum (Anokye et al., 2018). While fathers have received less attention in the literature, a recent meta-analysis reported that the prevalence of paternal depression is around 8.75% in the first year postpartum (Rao et al., 2020). Therefore, even if the prevalence of fathers’ depressive symptoms is less documented, it appears to be similar to what is observed in mothers during the postpartum period.

Among the different factors associated with postpartum depressive symptoms, infant sleeping arrangements have been considered in a few studies, but have led to conflicting results. One study showed that co-sleeping (room and bedsharing) beyond 6 months postpartum was associated with more maternal depressive symptoms and greater social criticism, even after controlling for preferred sleeping arrangement (Shimizu & Teti, 2018). On the contrary, another study showed that bedsharing was associated with fewer maternal depressive symptoms (Taylor et al., 2008).

Since the association between sleeping arrangements and depressive symptoms is not consistent among studies, it is necessary to identify other factors that could explain the contradictory results. Few studies considered whether co-sleeping was perceived as being problematic by mothers. Mothers’ attitudes and expectations related to their infant and parenthood are important and have been linked to maternal depressive symptoms (Church et al., 2005; Mihelic et al., 2016). However, even if unrealistic expectations have been identified as a risk factor for poor parental adjustment during the transition to parenthood, they have not been studied in relation to sleep or sleeping arrangement (Barimani et al., 2017).

The combination of conflicting safety concerns from experts around co-sleeping and the cultural preferences against its practice in Western countries (Barry, 2019) can lead to uncertainty in mothers about what constitutes the best sleeping arrangement for their infant. Importantly, studies have also highlighted that parenting practices may differ from what parents had anticipated before having a child (Mihelic et al., 2016). The presence of a discrepancy between planned and actual sleeping arrangement might therefore be as important as the sleeping arrangement itself, with regard to parental well-being.

Including Fathers

Family dynamics have changed dramatically in Western industrialized countries over the past 10–20 years (Diniz et al., 2021). Fathers are increasingly involved in family life and childcare; yet, perceptions of co-parenting differ in mothers and fathers (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2022). Therefore, a systemic perspective is necessary to better understand family functioning. However, as in other fields of child development, very few studies investigating infant sleep or sleep-related practices include fathers (Millikovsky-Ayalon et al., 2015).

In one study where mothers and fathers of infants 5–29 months old (n = 48) were asked to interpret hypothetical vignettes related to infant sleep, mothers and fathers interpreted infant sleep behavior differently (Sadeh et al., 2007). Fathers were more inclined to interpret hypothetical sleep problems vignettes as excessive infant demandingness and to endorse limit-setting behavior, compared to mothers. Regarding sleeping arrangement more specifically, a preliminary quantitative study described that mothers (N = 100) and fathers (N = 38) from different couples reported similar reasons (such as their sleep arrangement being beneficial for their own or their child’s sleep quality) for co-sleeping with their preschool-aged children (Germo et al., 2007). However, participants of that study were recruited as two different samples and were not part of the same family (fathers were not spouses drawn from the mothers’ sample). Therefore, whether mothers and fathers within the same couple have similar parental attitudes regarding sleeping arrangements remains to be determined.

In summary, studies examining the link between infant sleeping arrangement and postpartum depressive symptoms have yielded conflicting results. Furthermore, parental expectations about these arrangements are seldom considered, and pediatric sleep studies rarely include fathers. Documenting sleep-related parental attitudes would help to better understand the experience of both mothers and fathers who choose to practice either a co-sleeping or solitary sleeping arrangement, especially considering the increasing percentage of families practicing co-sleeping. Thus, the aims of this study were to: (1) compare parental attitudes regarding sleeping arrangements (solitary sleeping vs. co-sleeping) between mothers and fathers; it is expected that mothers and fathers from the same couple will have different attitudes toward co-sleeping, with mothers being more favorable toward co-sleeping; (2) explore the associations between actual sleeping arrangements (solitary sleeping, room sharing, bedsharing), the discrepancy between expected and actual sleeping arrangements, parental attitudes toward co-sleeping and depressive symptoms, in both mothers and fathers; it is hypothesized that parents whose infants sleep alone will report fewer depressive symptoms than parents who practice co-sleeping with their infants. Hence, a greater difference between actual and expected sleep arrangement will be associated with more depressive symptoms for both mothers and fathers. Considering that parents’ sex (Girgus & Yang, 2015), feeding method (Volkovich et al., 2015) and level of education (Di Florio et al., 2017) have been associated with both sleeping arrangements and depressive symptoms, these factors will also be considered as potential covariables.

Method

Participants

Primiparous and multiparous parents of 6-month-old infants from a large Canadian metropolitan area were recruited through social media groups and word of mouth. A total of 112 parents were enrolled in the study. Twenty parents provided limited data and were thus omitted from the final sample. Therefore, the final sample comprised 92 parents (82 participants from 41 heterosexual couples and 10 parents who participated in the study without their partner). Mothers’ ages ranged from 26 to 40 years (N = 48, M = 33.1, SD = 3.8), and fathers’ ages ranged from 26 to 52 years (N = 44, M = 35.1, SD = 5.4). The majority of participants (85.7% of fathers, 98% of mothers) had completed some postsecondary education. Most families had one (43.1%) or two (41.2%) children (Table 1). Exclusion criteria were the presence of serious obstetric complications, chronic illness, or any serious medical condition; mothers and fathers with a history of depression or anxiety; and infants with severe complications during delivery, serious medical condition, or who were born prematurely (<37 weeks). Parents had to be fluent in French or English in order to participate in the study. Written, informed consent was obtained from all parents. This study was overseen by the Research Ethics Board of the (blinded for the review process). Participants who were excluded due to missing data (n = 20) were compared to participants included in the final sample using independent samples t-tests on sociodemographic variables and main outcomes, with a confidence interval fixed at p < 0.10. While mothers in the final sample were less educated than mothers who were excluded (p < 0.10), fathers did not differ on any sociodemographic or outcome variables. Education was included as a covariate in order to control for potential confounding effects.

Procedure

After obtaining consent, research assistants (RA) scheduled a first home visit during which both parents were given separate questionnaire packages assessing depressive symptoms, sleep practices, attitudes toward sleeping arrangements and sociodemographic data. RAs explained to parents that they should complete their questionnaires separately and that there were no right or wrong answers. Questionnaires were left to be completed by the families and a second visit was scheduled to retrieve them two weeks later. During the second visit the RA verified completion of the questionnaires and asked the parents to complete any unanswered questions. Mothers’ and fathers’ questionnaires assessing depressive symptoms were reviewed during the second visit by the RA to offer psychological resources if needed. Families received a $20 (CAN) compensation for their participation.

Measures

Parental depressive symptoms

Severity of depressive symptoms was assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). This 20-item measure evaluates how often over the past week individuals experienced symptoms associated with depression (e.g., restless sleep, poor appetite, feeling lonely). Each item is rated on a Likert scale from 0 to 3 (0 = Rarely or none of the time, 1 = Some or little of the time, 2 = Moderately or much of the time, 3 = Most or almost all the time). Total scores range from 0 to 60, with high scores indicating more depressive symptoms. The CES-D has good psychometric properties and has been used in a variety of contexts, including with parents, as well as with community and clinical samples (Field et al., 2006; Irwin et al., 1999; Radloff, 1977; Zimmerman & Coryell, 1994). Cronbach’s alpha value for the present sample was 0.88 when both parents were pooled together.

Sleep Practices Questionnaire

The Sleep Practices Questionnaire (SPQ, Keller & Goldberg, 2004) assesses infant sleeping arrangements and infant sleep-related parental perceptions. The sleep location item was used to determine the infant’s sleeping arrangement (Where does your baby usually sleep at night?) at 6 months. Possible choices are that infants (1) Sleep alone in their own bed in their own room; (2) In a room shared with brothers and/or sisters; (3) In a bed or a crib in the same room as their parents (near or far from the parent’s bed); (4) In the same bed as their parents part of the night or all night. Three categories were created: solitary sleeping from their parents (choices 1 and 2), room sharing (infants in the same room as parents but not in the same bed; choice 3), and bedsharing (choice 4).

Another SPQ item was used to assess the discrepancy between the infant’s expected sleeping arrangement and the actual sleeping location: Does your baby sleep where you expected he/she would? This item was rated on a five-point scale (1 = Yes, he/she definitely sleeps where I expected he/she would, 3 = Sometimes he/she sleeps where I expected he/she would, and 5 = No, he/she does not sleep at all where I expected he/she would.).

The Parental Sleep Attitudes Scale (PSAS) from the SPQ measuring attitudes toward co-sleeping was used. The scale comprises 8 items rated on a six-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree; 6 = Strongly agree). Negatively worded items were reverse scored before calculating the scale’s total score on a possible aggregate of 8–48. High scores indicate more favorable views toward co-sleeping arrangements. Means were calculated for the 8 items and possible results range from 0 to 5. In the present sample Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.81 when both parents were pooled together.

Statistical Analyses

Parental attitudes and perceptions about infant sleeping arrangement were compared between mothers and fathers within each couple using paired t-tests. A correlation table was generated to identify potential variables to control for in subsequent analyses. To test our main hypotheses, a linear mixed model, with parents as the within-subject factor, was built in a two-step process. First, a selection was made among the confounding variables. Pearson correlations were calculated between the depression score and each of the possible confounding variables (number of children in the family, feeding method, age of parent, level of education) for mothers and fathers separately. All statistically significant confounders for at least one parent, at r ≥ 0.2, were included in the multivariate linear mixed model, with the depression score as the dependent variable. The independent variables pertaining to our main hypotheses (attitudes toward co-sleeping, actual sleeping location (solitary, room sharing, bedsharing) and the discrepancy between expected and actual sleeping arrangement) were included in the model. To assess within-couple differences an interaction term was added for each predictor (mother, father, couple). The final model was attained after excluding the interaction terms and the main effects that were not significant at p < 0.05. The percentage of explained variance was estimated separately for mothers and fathers.

Results

Correlations between Sociodemographic and Outcome Variables

Pearson correlations are reported in Table 2. Older mothers reported more children in the family (p < 0.01). Mothers (p < 0.01) and fathers (p < 0.05) of breastfed infants reported a higher level of education. A higher number of children in the family was associated with fewer reported depressive symptoms by fathers (p < 0.05). Feeding method was not associated with other confounding variable or depressive symptoms; therefore, it was not included in further analyses.

Comparing Parents’ Perceptions of Infant Sleep Arrangements and Depressive Symptoms

Comparisons of sleep-related parental perceptions and depressive symptoms between mothers and fathers are reported in Table 3. Parents who participated without their partner were excluded from this analysis. Within the same couple, mothers were more favorable toward co-sleeping than fathers (2.74 ± 0.16 vs. 2.19 ± 0.11, p < 0.01). Levels of agreement between expected and actual sleep location as well as depressive symptoms did not differ between mothers and fathers from the same couple.

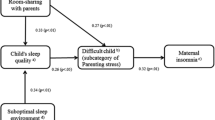

Factors Associated with Depressive Symptoms in Mothers and Fathers

Table 4 shows results of the multivariate linear mixed model for mothers, fathers, and both parents combined. Attitudes toward co-sleeping were not significantly associated with depressive symptoms and were therefore excluded from the final model (p > 0.05). Depressive symptoms were significantly associated with parents’ level of education (p < 0.05), number of children in the family (p < 0.05) and the discrepancy between expected and actual sleeping arrangements (p < 0.01). Lower levels of parental education and a higher number of children in the family were associated with fewer depressive symptoms, but specifically in fathers. Sleeping arrangements were not associated with depressive symptoms in either parent. However, a greater discrepancy between expected and actual sleeping arrangement was linked to higher levels of depressive symptoms for mothers and fathers.

Discussion

The present study highlights that within the same couple, mothers were usually more favorable than fathers toward co-sleeping. While multivariate linear mixed model analyses did not show an association between actual sleeping arrangement and depressive symptoms, the presence of a discrepancy between expected and actual sleeping arrangement was associated with more depressive symptoms in both mothers and fathers, even after controlling for the actual sleep location.

Comparing Parents’ Perceptions of Infant Sleep Arrangements

As hypothesized, our results show that mothers were generally more favorable than their male partners toward co-sleeping. These results are in line with previous studies documenting differences between mothers and fathers regarding infant sleep-related perceptions based on hypothetical vignettes (Sadeh et al., 2007). In that study, authors reported that fathers were more likely than mothers to interpret infant demands as being excessive, and to support a limit-setting attitude. In contrast, mothers were more inclined to perceive the child as experiencing distress. Present results are also consistent with the study of Germo et al. (2007) showing that fathers of reactive co-sleepers favored solitary sleeping arrangements as opposed to co-sleeping. Taken together, these results suggest that mothers and fathers have divergent attitudes, cognitions and interpretations related to their infant’s sleep and support the need to include both mothers and fathers in sleep-related studies to better understand family functioning as a whole.

Factors Associated with Depressive Symptoms in Mothers and Fathers

Parental depressive symptoms were significantly associated with the discrepancy between expected and actual sleeping arrangements, after controlling for confounding variables. Parental attitudes toward co-sleeping were not related to parental depressive symptoms.

Actual sleep location

Contrary to what was hypothesized, even though attitudes differed between mothers and fathers, there was no association between depressive symptoms and actual sleep location in either parent. These results are in contrast with a study reporting that solitary sleeping arrangement at 3 months predicted more maternal depressive symptoms at 6 months (Volkovich et al., 2015). Greater consistency and frequency of co-sleeping has also been linked to fewer maternal depressive symptoms at 9 months postpartum (Taylor et al., 2008). A qualitative study reports that in some parents of toddlers (0–3 years old), closeness, touch, and co-sleeping (bed and room sharing) were strategies to promote sleep for all family members (Gustafsson et al., 2021). It seems that co-sleeping arrangements might be associated with a positive mood in some parents, which is likely due to parent-infant co-regulation of physiological (thermoregulation, breathing, circadian rhythm coordination, nighttime synchrony, and heart rate variability) and socioemotional (attachment and cortisol activity) development, as suggested in a recent conceptual paper (Barry, 2022).

On the contrary, another study shows contradictory results where mothers who practiced co-sleeping (room and bedsharing) beyond 6 months reported more depressive symptoms than mothers of infants who slept alone by 6 months of age, after controlling for preferred sleep arrangement (Shimizu & Teti, 2018). These divergent results could be partially explained by the inconsistency in the co-sleeping definition among the different studies. The present results suggest that parental expectations related to a co-sleeping arrangement (i.e., intentional as opposed to reactive co-sleeping) could explain these inconsistent results.

Disparity between expected and actual sleeping arrangements

Interestingly, in the present study, parents who perceived less disparity between expected and actual sleeping arrangements experienced fewer depressive symptoms, even after considering the actual sleep location, with a small effect size. Present findings are consistent with our hypothesis and with a study showing negative outcomes, specifically in parents practicing reactive co-sleeping (room and bedsharing), while night awakenings were not being perceived as being problematic in families practicing planned co-sleeping (Keller & Goldberg, 2004). This is of major importance, since bedsharing is rarely planned in Western industrialized countries, but nonetheless is practiced by a third of the general population (Gilmour et al., 2019). Hence, studies have highlighted that a majority of parents who co-slept had not initially planned on doing so (Powell & Karraker, 2017). This underlines the potential impact of discrepancies between parental expectations and the infant’s actual sleeping arrangements.

The presence of a discrepancy between expectations and reality also seems to impact what parents consider “normal” or “pathological” sleep. On one end of the continuum, some parents perceive their infant’s sleep behaviors as being problematic (i.e., nocturnal awakenings), even if these behaviors do not meet the diagnostic criteria for a sleep disorder (Mindell et al., 2022). On the other end of the continuum, parents feel their child’s sleep behaviors are normal considering the current developmental stage (Ramos et al., 2007). Authors have shown that parents of reactive co-sleepers perceive their child’s sleep behaviors as being more problematic than parents of intentional or planned co-sleepers (Ramos et al., 2007). Parents who perceive their child’s sleep arrangement as problematic may be at greater risk of developing depressive symptoms. It is possible to imagine that parents have unrealistic expectations about infant sleep, leading them to view their child’s sleep as problematic. A better understanding of the reasons why parents act differently than what they had planned would provide a clearer description of the link between parental expectations and depression.

Confounding variables

Demographic variables such as parental age and breastfeeding were not significantly associated with parental depressive symptoms. Nevertheless, parental education was associated with depressive symptoms, but specifically in fathers. Lower levels of parental education were related to lower levels of depressive symptoms for fathers, with a moderate effect size. Contrary to our results, a study examining depression in a large cohort of fathers of older children (5–17 years old) found that lower levels of education were associated with higher depression scores, although this association was not significant after adjusting for confounders such as poverty status (Rosenthal et al., 2013). In the present sample, the association between education and depressive symptoms was not significant in mothers. However, a review article showed that lower educational level was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms (Musliner et al., 2016). Studies with a larger sample size would help clarify this question.

Having more children was associated with fewer paternal depressive symptoms. These results differ from previous research suggesting primiparous and multiparous fathers experience similar frequencies of postpartum depressive symptoms (Wells & Aronson, 2021).

Targeted recommendations about infant sleep arrangement could be tailored differently for primiparous and multiparous parents to address expectations in a manner that is sensitive to their reality of negotiating one or more sleep routines. In the field of pediatric sleep, studies should include fathers and mothers of the same couple since variables can have differential effects depending on the sex of the parent. This proposition is similar to that of other researchers suggesting that studies include both parents within a family using an ecological systems perspective (Volling et al., 2019).

Limitations and Future Directions

Overall, the present sample is relatively small and highly educated; thus, the results, especially the correlations, should be interpreted with caution. However, families who participated in the study have similar characteristics to the general population of the surrounding area in terms of the number of children in the family (Statistics Canada, 2016). More than two-thirds of mothers in our sample reported exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum; this is higher than numbers reported in a national survey, suggesting that one-third to two-fifths of Canadian mothers exclusively breastfed until at least 6 months postpartum (Statistics Canada 2018). However, it is congruent with the high level of education found in our sample since breastfeeding is generally correlated with education (Buckman et al., 2020). The proportion of parents practicing bedsharing in our sample is similar to what was found in another study reporting that 27% of mothers bedshared occasionally (Gilmour et al., 2019). Lastly, the present study does not establish the directionality of the association between depressive symptoms and sleeping arrangements. Thus, it is possible that depressive symptoms influence co-sleeping patterns.

Future studies should investigate parental attitudes and expectations regarding infant sleeping arrangements in a larger sample size and examine how parental patterns evolve over time. Research should examine both parents within the same couple and examine not only the actual sleeping arrangement but also the discrepancy between the expected and actual sleep location. This topic would also benefit from being investigated in different cultures and at different timepoints throughout infant development. Assessing parents’ region of birth could provide additional insight about parental expectations regarding sleep arrangement (Gilmour et al., 2019). Information regarding parents’ involvement with their infant at night could contribute to a better understanding of the link between parental expectations about infant sleep and depressive symptoms. Finally, future research with a larger sample of participants should further disentangle the concepts of room sharing or bedsharing in the association between parental expectations and parental adjustment.

Conclusion

It seems that a mismatch sometimes exists between sleeping arrangements during infancy and what parents had originally planned. Moreover, reactive sleeping arrangements are associated with more depressive symptoms regardless of attitudes or parental divergence about co-sleeping. Yet, health professionals, family and friends may express different opinions than parents regarding their choice of sleeping arrangement based on their personal experiences and culture. This might lead to negative perceptions by parents who deviate from the cultural model of sleep. Therefore, health professionals should ask questions not only about sleep location, but also about parents’ expectations toward their sleep arrangement and how they came to implement it.

References

Anokye, R., Acheampong, E., Budu-Ainooson, A., Obeng, E. I., & Akwasi, A. G. (2018). Prevalence of postpartum depression and interventions utilized for its management. Annals of General Psychiatry, 17(1), 1–8.

Barba-Müller, E., Craddock, S., Carmona, S., & Hoekzema, E. (2019). Brain plasticity in pregnancy and the postpartum period: links to maternal caregiving and mental health. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 22(2), 289–299.

Barimani, M., Vikström, A., Rosander, M., Forslund Frykedal, K., & Berlin, A. (2017). Facilitating and inhibiting factors in transition to parenthood–ways in which health professionals can support parents. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 31(3), 537–546.

Barry, E. S. (2021). Sleep consolidation, sleep problems, and co-sleeping: Rethinking normal infant sleep as species-typical. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 182(4), 183–204.

Barry, E. S. (2022). Using complexity science to understand the role of co-sleeping (bedsharing) in mother-infant co-regulatory processes. Infant Behavior and Development, 67, 101723.

Barry, E. S. (2019). Co-Sleeping as a developmental context and its role in the transition to parenthood. In Transitions into Parenthood: Examining the Complexities of Childrearing. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Blair, P. S., Sidebotham, P., Evason-Coombe, C., Edmonds, M., Heckstall-Smith, E. M., & Fleming, P. (2009). Hazardous cosleeping environments and risk factors amenable to change: case-control study of SIDS in south west England. BMJ, 339, b3666.

Buckman, C., Diaz, A. L., Tumin, D., & Bear, K. (2020). Parity and the association between maternal sociodemographic characteristics and breastfeeding. Breastfeeding Medicine, 15(7), 443–452.

Church, N. F., Brechman-Toussaint, M. L., & Hine, D. W. (2005). Do dysfunctional cognitions mediate the relationship between risk factors and postnatal depression symptomatology? Journal of Affective Disorders, 87(1), 65–72.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587.

Colson, E. R., Willinger, M., Rybin, D., Heeren, T., Smith, L. A., Lister, G., & Corwin, M. J. (2013). Trends and factors associated with infant bed sharing, 1993-2010: the National Infant Sleep Position Study. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(11), 1032–1037.

Colvin, J. D., Collie-Akers, V., Schunn, C., & Moon, R. Y. (2014). Sleep environment risks for younger and older infants. Pediatrics, 134(2), e406–e412.

Diniz, E., Brandao, T., Monteiro, L., & Veríssimo, M. (2021). Father involvement during early childhood: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 13(1), 77–99.

Field, T., Diego, M., Hernandez-Reif, M., Figueiredo, B., Deeds, O., Contogeorgos, J., & Ascencio, A. (2006). Prenatal paternal depression. Infant Behavior and Development, 29(4), 579–583.

Di Florio, A., Putnam, K., Altemus, M., Apter, G., Bergink, V., Bilszta, J., & Devouche, E. (2017). The impact of education, country, race and ethnicity on the self-report of postpartum depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Psychological Medicine, 47(5), 787–799.

Germo, G. R., Chang, E. S., Keller, M. A., & Goldberg, W. A. (2007). Child sleep arrangements and family life: Perspectives from mothers and fathers. Infant and Child Development, 16(4), 433–456.

Gilmour, H., Ramage-Morin, P. L., & Wong, S. L. (2019). Infant bed sharing in Canada. Health Rep, 30(7), 13–19.

Girgus, J. S., & Yang, K. (2015). Gender and depression. Current Opinion in Psychology, 4, 53–60.

Gustafsson, S., Jacobzon, A., Lindberg, B., & Engström, Å. (2022). Parents’ strategies and advice for creating a positive sleep situation in the family. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 36, 830–838.

Irwin, M., Artin, K. H., & Oxman, M. N. (1999). Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Archives of Internal Medicine, 159(15), 1701–1704.

Keller, M. A., & Goldberg, W. A. (2004). Co‐sleeping: Help or hindrance for young children’s independence? Infant and Child Development, 13(5), 369–388.

Kettunen, P., Koistinen, E., & Hintikka, J. (2014). Is postpartum depression a homogenous disorder: time of onset, severity, symptoms and hopelessness in relation to the course of depression. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1), 1–9.

McKenna, J. J., & McDade, T. (2005). Why babies should never sleep alone: a review of the co-sleeping controversy in relation to SIDS, bedsharing and breast feeding. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 6(2), 134–152.

Messmer, R., Miller, L. D., & Yu, C. M. (2012). The relationship between parent‐infant bed sharing and marital satisfaction for mothers of infants. Family Relations, 61(5), 798–810.

Mihelic, M., Filus, A., & Morawaska, A. (2016). Correlates of prenatal parenting expectations in new mothers: is better self-efficacy a potential target for preventing postnatal adjustment difficulties? Prevention Science, 17(8), 949–959.

Mileva-Seitz, V. R., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Battaini, C., & Luijk, M. P. (2017). Parent-child bed-sharing: the good, the bad, and the burden of evidence. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 32, 4–27.

Millikovsky-Ayalon, M., Atzaba-Poria, N., & Meiri, G. (2015). The role of the father in child sleep disturbance: child, parent, and parent-child relationship. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(1), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21491.

Mindell, J. A., Collins, M., Leichman, E. S., Bartle, A., Kohyama, J., Sekartini, R., & Goh, D. Y. (2022). Caregiver perceptions of sleep problems and desired areas of change in young children. Sleep Medicine, 92, 67–72.

Musliner, K. L., Munk-Olsen, T., Eaton, W. W., & Zandi, P. P. (2016). Heterogeneity in long-term trajectories of depressive symptoms: Patterns, predictors and outcomes. Journal of Affective Disorders, 192, 199–211.

O’Hara, M. W., & Wisner, K. L. (2014). Perinatal mental illness: definition, description and aetiology. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 28(1), 3–12.

Powell, D. N., & Karraker, K. (2017). Prospective parents’ knowledge about parenting and their anticipated child‐rearing decisions. Family Relations, 66(3), 453–467.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Ramos, K. D., Youngclarke, D., & Anderson, J. E. (2007). Parental perceptions of sleep problems among co‐sleeping and solitary sleeping children. Infant and Child Development, 16(4), 417–431.

Rao, W.-W., Zhu, X.-M., Zong, Q.-Q., Zhang, Q., Hall, B. J., Ungvari, G. S., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2020). Prevalence of prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers: A comprehensive meta-analysis of observational surveys. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 491–499.

Rosenthal, D. G., Learned, N., Liu, Y.-H., & Weitzman, M. (2013). Characteristics of fathers with depressive symptoms. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17(1), 119–128.

Sadeh, A., Flint-Ofir, E., Tirosh, T., & Tikotzky, L. (2007). Infant sleep and parental sleep-related cognitions. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(1), 74.

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Nuttall, A. K., & Berrigan, M. N. (2022). Couple, parent, and infant characteristics and perceptions of conflictual coparenting over the transition to parenthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(4), 908–930.

Shimizu, M., & Teti, D. M. (2018). Infant sleeping arrangements, social criticism, and maternal distress in the first year. Infant and Child Development, 27(3), e2080.

Smith, B. P., Hazelton, P. C., Thompson, K. R., Trigg, J. L., Etherton, H. C., & Blunden, S. L. (2017). A multispecies approach to co-sleeping. Human Nature, 28(3), 255–273.

Statistics Canada (2016). Recensement du Canada de 2016, compilation effectuée par le ministère de la Famille à partir des données du tableau B2 de la commande spéciale CO-1758.

Statistics Canada (2018). Exclusive breastfeeding, at least 6 months, by age group.

Taylor, N., Donovan, W., & Leavitt, L. (2008). Consistency in infant sleeping arrangements and mother–infant interaction. Infant Mental Health Journal, 29(2), 77–94.

Tully, K. P., Holditch-Davis, D., & Brandon, D. (2015). The relationship between planned and reported home infant sleep locations among mothers of late preterm and term infants. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(7), 1616–1623.

Volkovich, E., Bar-Kalifa, E., Meiri, G., & Tikotzky, L. (2018). Mother–infant sleep patterns and parental functioning of room-sharing and solitary-sleeping families: a longitudinal study from 3 to 18 months. Sleep, 41(2), zsx207.

Volkovich, E., Ben-Zion, H., Karny, D., Meiri, G., & Tikotzky, L. (2015). Sleep patterns of co-sleeping and solitary sleeping infants and mothers: a longitudinal study. Sleep Medicine, 16(11), 1305–1312.

Volling, B. L., Cabrera, N. J., Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D. E., McDaniel, B. T., Liu, S., Almeida, D., Lee, J. ‐K., Schoppe‐Sullivan, S. J., Feng, X., Gerhardt, M. L., Dush, C. M. K., Stevenson, M. M., Safyer, P., Gonzalez, R., Lee, J. Y., Piskernik, B., Ahnert, L., Karberg, E., Malin, J., Kuhns, C., Fagan, J., Kaufman, R., Dyer, W. J., Parke, R. D., & Cookston, J. T. (2019). Advancing research and measurement on fathering and children’s development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 84(1), 7–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12404.

Wells, M. B., & Aronson, O. (2021). Paternal postnatal depression and received midwife, child health nurse, and maternal support: A cross-sectional analysis of primiparous and multiparous fathers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 280, 127–135.

Zimmerman, M., & Coryell, W. (1994). Screening for major depressive disorder in the community: A comparison of measures. Psychological Assessment, 6(1), 71.

Funding

The research leading to these results was funded by the Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQS) under Grant Agreement; the Research Center of Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal; Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC); and the clinical doctorate programs of the Université de Montréal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analyses were performed by all authors as well. The first draft of the manuscript was written by G.C.-L., S.K., M.-H.P., and M.-J.B. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The protocol, questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the ethics committees of the Hôpital en Santé mentale Rivière-des-Prairies (HRDP) of the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux (CIUSSS) du Nord-de-l’Île-de-Montréal and McGill University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chénier-Leduc, G., Béliveau, MJ., Dubois-Comtois, K. et al. Parental Depressive Symptoms and Infant Sleeping Arrangements: The Contributing Role of Parental Expectations. J Child Fam Stud 32, 2271–2280 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02511-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02511-x