Why is it so hard to compensate people for serious vaccine side effects?

Though very rare, complications from shots can shatter lives and trust. Now the federal programs designed to help them are struggling with COVID-19.

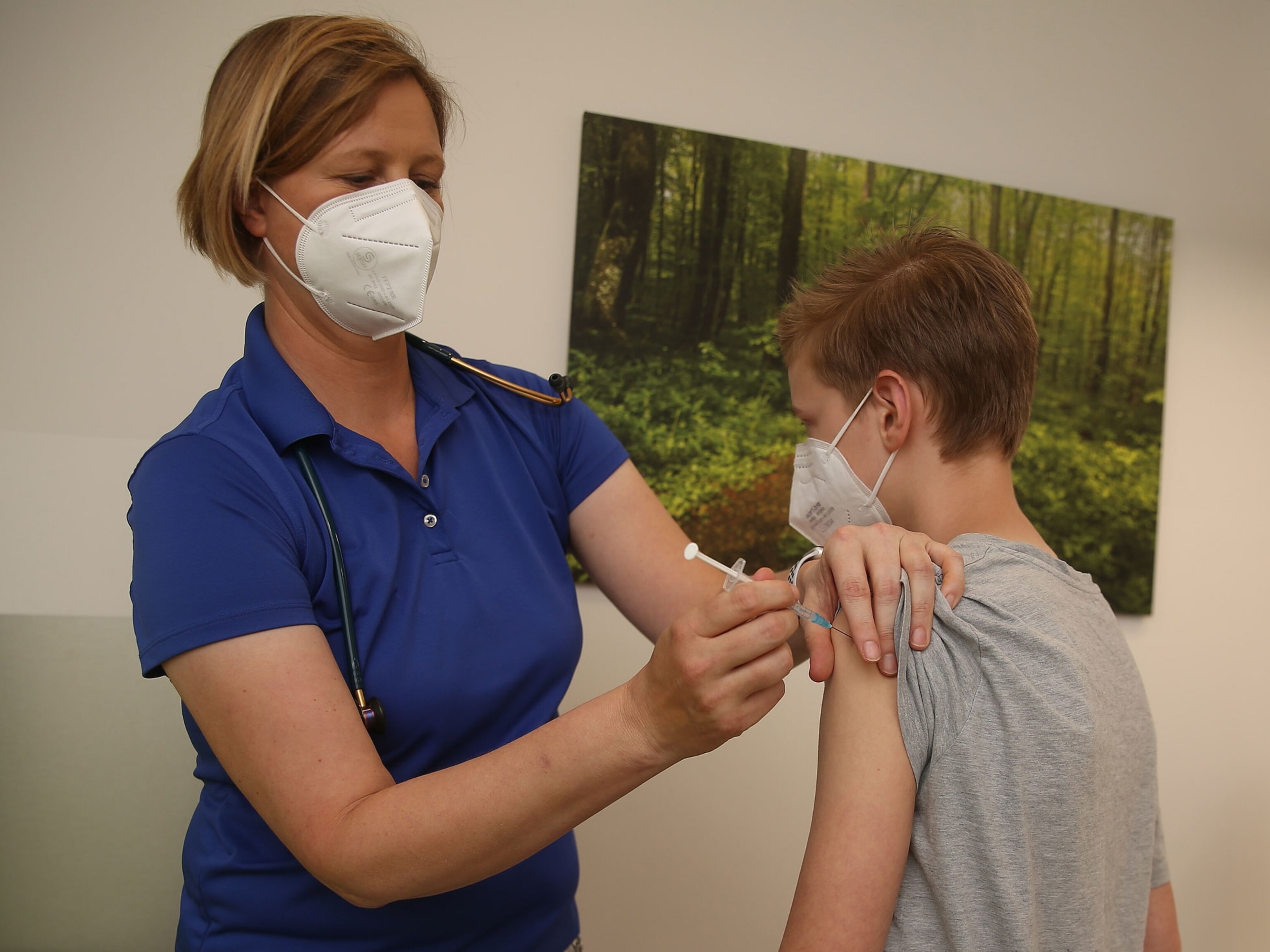

From the start, 14-year-old Aiden Ekanayake and his mom Emily didn’t question whether Aiden would get a COVID-19 vaccine. “We take COVID extremely seriously, so our plan has always been to vaccinate,” Emily says. Aiden was “pretty excited for it” because it meant doing more activities and worrying less about getting sick. And though Emily had heard about possible side effects, she knew they were usually mild.

Aiden got his first dose of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine on May 12, 2021, the day it came available for people his age. Four weeks later he got his second dose. The very next day Aiden began feeling mild chest pain. He dismissed it, assuming it was related to his asthma, but the pain kept waking him up that night.

“I began to get frightened because I was able to fall back asleep and then woke up an hour later with the same pain,” Aiden says. He woke his mother at dawn, and Emily recognized the signs of myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart known to occur in rare cases after the Pfizer vaccine.

Aiden spent four days in the acute cardiac unit at their local hospital, where he was given anti-inflammatory drugs for the pain. After discharge, Aiden discovered that any activity that raised his heart rate could still trigger mild chest pain. Though he’s expected to fully recover, his parents are watching the medical bills roll in, despite their insurance coverage. “We did everything we were told to do, and we shouldn’t be paying the price in more than one way,” Emily says. “It’s adding insult to injury.”

Emily discovered that two U.S. programs exist for compensating people with severe side effects likely caused by immunizations. But only one of these programs covers COVID-19 vaccines, and so far it hasn’t actually paid any claims. Some experts question whether it ever will. This ambiguity isn’t just a problem for those with injuries. When people don't know if they'll be compensated for legitimate vaccine injuries, or when those who do get them feel dismissed and abandoned, it erodes vaccine confidence.

“Vaccine hesitancy stems from lack of public trust,” says Maya Goldenberg, who studies vaccine hesitancy at the University of Guelph in Ontario. As of March about 216 million people are fully vaccinated in the U.S., but 16 percent of Americans still refuse to get the vaccine, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. A previous survey found that one in five people cite side effects as the top reason for not getting vaccinated. “People need to be confident that vaccines are safe and effective when they make a decision to get vaccinated. They also need to know that, insofar as there are real dangers involved, people will be cared for and not stranded in that rare situation.”

Without a robust compensation program, the resulting loss of trust further fuels anti-vaccine advocacy and increases vaccine hesitancy, hindering efforts to reach herd immunity.

“Vaccination is not a per-individual benefit, it’s for societal benefit, and when someone is injured by that vaccine, I think society owes that individual compensation,” says Walter Orenstein, associate director of the Emory Vaccine Center in Atlanta. “People who are willing to get the vaccine are helping our society. Obviously, the vast majority are not injured, but we need some mechanism in place to compensate people legitimately harmed.”

All vaccines have risks

Like any drug, vaccines have side effects. But they’re required to have a far better safety record than other pharmaceutical products because they’re given to prevent disease. Most vaccine side effects are therefore mild and temporary. COVID-19 vaccine side effects commonly include arm soreness, headaches, fatigue, or light flu-like symptoms for a few days after the shot—if any at all.

But in rare cases, patients have developed far more serious complications.

Jessica McFadden, a 44-year-old fundraising officer in Indiana, chose to get the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in early April because a single shot was more appealing than a two-dose vaccine. But one week after her jab, breathing became increasingly difficult. By late April a coughing fit required her to lay down to breathe. A CT scan showed a pulmonary embolism, a blood clot wedged in a lung artery. More imaging revealed another clot headed straight to McFadden’s heart.

The cardiologist told her she needed emergency surgery, adding “you have 12 hours to live,” McFadden recalls. “At that point I had to call my husband and give him a goodbye message.”

Doctors ultimately removed the clot near her heart, several from her lungs, another in her leg, and two from her brain. McFadden spent five days recovering in the ICU from a diagnosis of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome, or TTS, an extremely rare adverse event that can occur after the J&J vaccine. TTS occurs in approximately four people per million doses, but its severity led the CDC to recommend mRNA vaccines over the J&J shot in December.

Since it’s not possible to create vaccines without any potential severe reactions, medical ethicists say that governments encouraging vaccination have a moral obligation to compensate those experiencing such events.

“You do want to try to be generous toward the individual who may have been harmed, and you buffer that slightly with the moral principle of encouraging what you honestly believe to be safe, effective, and important vaccines,” says Art Caplan, a bioethicist at the New York University.

McFadden accepts that tradeoff, but she’s vexed that the government has pushed so hard for everyone to get vaccinated and not pushed to compensate those like her who were harmed. “It’s like [we’re] the cost of doing business in a pandemic,” she says. McFadden is fortunate to have good health insurance—though her bills after insurance still exceeded $7,000—and her sick leave covered all but two weeks of missed work.

But others may lack paid sick leave or insurance coverage, leaving them even more vulnerable in the rare event a vaccine causes serious side effects.

Anna Kirkland, a professor of women’s and gender studies at the University of Michigan and author of Vaccine Court: The Law and Politics of Injury, says the country’s already fragmented and inequitable healthcare system makes it even more important that an injury compensation program functions efficiently.

“Vaccine injury compensation may be a last line of support for families confronting devastating or lifelong medical conditions because we don't have a medical or social safety net that reliably keeps sick and disabled people out of poverty in this country,” Kirkland says. “Medical bills are a major cause of bankruptcies.”

That’s what Chelsea Giovanni, a mother of a high school athlete in Utah, fears. Her son Kam worked at a fast-food restaurant and figured he’d be required to get vaccinated, so he got the Pfizer jab in late September. Like Aiden, he developed myocarditis with severe chest pain and spent six days in the hospital, including treatment with intravenous immune globulin—a common therapy for myocarditis—in the cardiac ICU. He was released for light duty work a month later, but he was not cleared for sports. He missed basketball and baseball seasons and remains sidelined now as football spring training begins.

“This vaccine has screwed up any chance he had of getting a sports scholarship,” Giovanni says. Though insurance has covered about $125,000 of Kam’s $350,000 in medical bills, the company won’t pay more because his condition was caused by a vaccine. Even with financial assistance from the hospital, Giovanni can’t afford the $15,000 she owes, leaving her seeking donations.

Origin of the vaccine court

The U.S. vaccine injury compensation program has roots in the early 1980s, when a slew of lawsuits from parents alleging that their children suffered severe vaccine injuries began costing pharmaceutical companies so much money in litigation that several halted vaccine production or left the market, causing national vaccine shortages. By 1985 families were seeking a combined $3.16 billion in damages for just the diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT) vaccine—30 times that vaccine’s entire annual market share.

“It really brought home the risks to our system by not having a compensation program,” Emory’s Orenstein says.

Congress created the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) in 1986 under the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act, which established VICP as a “no-fault” system, funded by an excise tax on covered vaccines, to compensate families for injuries likely caused by vaccines.

“No-fault” means it’s not necessary to show wrongdoing or fault on the manufacturer’s part to receive damages, explains Dorit Reiss, a professor specializing in vaccine law at the University of California, Hastings. Families can still file suits against pharmaceutical companies for anything besides claiming the vaccine design is defective, but only after going through the vaccine court, which requires a lower level of proof to show a vaccine caused injury than standard courts do.

”The idea was to provide easier compensation for people who might have been injured,” says Dan Salmon, director of the Institute for Vaccine Safety at Johns Hopkins and a former director of vaccine safety at the National Vaccine Program Office. For the most part, experts say, that’s exactly what it’s done.

Then in 2005 President George W. Bush enacted the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act to protect pharmaceutical companies from financial liability for products developed to address public emergencies. The law bars people today from suing Pfizer, Moderna, or Johnson & Johnson for COVID-19 vaccine injury. The act also introduced the Countermeasure Injury Compensation Program (CICP) to cover any injuries arising from emergency measures, including non-routine immunizations, medical devices, and drugs.

Since COVID-19 vaccines were developed during a pandemic, they’re currently covered by the less robust CICP program, which has a lower budget than VICP and covers fewer expenses. Of more than 4,000 claims filed so far to CICP for COVID-19 vaccine injuries, the program has resolved five—all denied.

“We call the CICP program a black hole,” says Greg Rogers, a lawyer with Rogers Hofrichter & Karrah LLC in Atlanta who offered to help Emily Ekanayake file a claim pro bono. Nine months after Aiden’s vaccination, Emily still has no idea when—or if—she’ll receive any compensation for her son’s injury.

CICP versus VICP: What’s the difference?

The CICP’s track record pre-pandemic doesn’t inspire optimism. Of approximately 400 eligible cases, CICP compensated just 7 percent, totaling about $6 million. Nearly all the denied claims were related to a vaccine. VICP, meanwhile, has compensated 41 percent of resolved cases and paid out more than $4.6 billion since 1988.

But CICP was supposed to be only for interventions that are not widely distributed in the U.S., such as anthrax or Ebola vaccines, says Renee Gentry, a vaccine injury lawyer who has spent 25 years representing clients in VICP and who directs the Vaccine Injury Litigation Clinic at the George Washington University Law School. “It was never designed for something that was going to be administered to 70 percent of the American population.”

CICP’s shortcomings become especially evident in cases like that of Edmara Depaula, a mother of two in Concord, New Hampshire. After losing both her grandparents to COVID-19, Depaula overcame her uncertainty about the vaccine and decided to get it before anyone else in her household.

“I’m the healthiest one in the house, so if nothing happens to me, it will be safe for everybody else to take it,” Depaula says. “I thought I was doing the right thing.”

But the cramps, nausea, and fatigue she began feeling after the J&J vaccine never subsided. Two weeks after her vaccination, chest pain brought her to the hospital, where she spent the next nine days. Her doctors diagnosed her with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a condition affecting blood flow that isn’t well understood. One doctor suggested her symptoms could be a rare vaccine reaction and connected her with Gentry, who is helping Depaula file a CICP claim. Depaula says her health issues have completely changed her household dynamic as she struggles to do housework or play with her daughters.

“I keep asking myself, am I ever going to get better?” she says. “Am I going to one day go back to work and have a normal life? What if this is my new normal?”

Virtually no evidence links POTS with COVID-19 vaccination except a single case study, but VICP was devised to handle cases like that, Gentry says. Many vaccine injury claims filed to VICP are settled using a Vaccine Injury Table that streamlines the process for qualifying injuries. More complex cases take longer, sometimes dragging out for a decade as the court pores over the evidence to determine whether the vaccine might have caused a given condition.

Still, VICP requires the lowest standard of proof: “50 percent and a feather,” UC Hastings’ Reiss says. That is, the court rules for the plaintiff if the chance the vaccine caused the injury is just a smidge over 50 percent.

By contrast, CICP only compensates injuries if people provide “compelling, reliable, valid medical, and scientific evidence” that the countermeasure—a COVID-19 vaccine—led to the injury. That's an ambiguous standard that David Bowman, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, says via email is higher than the VICP one.

Unlike VICP, whose coverage includes pain and suffering up to $250,000, CICP compensates only for out-of-pocket medical expenses and lost wages up to $50,000. VICP has open proceedings and judicial appeal, but “none of those rights are available under CICP,” adds Michael Milmoe, a vaccine injury attorney at the law firm of Leah V. Durant, who spent nearly 30 years working in VICP in the Department of Justice. There’s no way to know who decides your case and no paid legal representation, whereas VICP covers all attorney costs for families seeking compensation. Claimants can appeal CICP decisions to a panel of non-CICP federal reviewers, but HHS makes the final decision. CICP doesn’t even have an injury table for COVID-19 vaccines, despite clear evidence linking them to conditions such as myocarditis and TTS that multiple experts say is sufficient for an injury table.

Lawyers who spoke with National Geographic said many people calling their offices aren’t sure whether to even file a claim to CICP without knowing whether COVID-19 vaccines will eventually be added to VICP. Adding a vaccine to VICP requires that the CDC recommend the vaccine for children or pregnant individuals—it has been since May—and that Congress pass an excise tax on the vaccine. Though the tax can be tacked onto any bill, it hasn’t been. Once added, a vaccine has a “lookback” period allowing anyone who had an injury from it in the previous eight years to file a claim.

But, “because this was a countermeasure, everything's treated differently,” Gentry says. There’s never been a completely new vaccine added to CICP that then becomes routinely recommended. No one knows if that lookback period will apply if COVID-19 vaccines are added to VICP—or whether applying to CICP now could block additional VICP compensation later.

“We’re worried because we don’t know what to tell clients,” Milmoe says, and people are running out of time. While VICP gives people three years to file a claim after a vaccine injury occurs, CICP’s statute of limitations is just one year after receiving the vaccine—which has already passed for many people.

When asked about these questions, Bowman at HHS wrote, “We cannot speculate about future actions.”

Reform on the horizon?

Adding COVID-19 vaccines to VICP would mean more people getting the compensation they deserve, but it would also compound a problem that’s been festering for years: VICP has been sagging under its own weight with the sheer volume of claims currently in the system.

“It’s an exceptionally well-run program, but it’s not efficient right now simply because it’s overwhelmed,” Gentry says.

When the program began, VICP covered just six childhood vaccines. Since then, another 10 vaccines have been added to the schedule, including the flu vaccine administered to approximately 175 million people—mostly adults—annually. The program wasn’t designed with adults in mind, but the influenza vaccine’s addition in 2005 led to an explosion of adult claims that now outnumber child cases.

“You’re talking about loss of work, inability to support a family,” says bioethicist Caplan. “These are things that didn't come up with kids.”

Per the 1986 law, VICP is supposed to resolve cases within a year, or 14 months at most. But it’s currently taking 12 to 16 months just to review a case to confirm all necessary documentation before the decision process even begins.

“They already have 4,000 cases and eight special masters [administrative judges who decide cases]. If COVID people start coming in, it’s going to destroy them,” Gentry says. “If you want a strong universal immunization program that people can count on, you have to have a vibrant safety net, and the safety net is about to collapse.”

Every expert who spoke with National Geographic agreed that reform for the vaccine court is long overdue. “It’s important in the middle of a pandemic that we maintain confidence in vaccines, and one way of doing that is compensating for injuries that meet the criteria,” says Saad Omer, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health. “These [processes] should be streamlined.”

U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett (Texas) has introduced two bills that would substantially improve vaccine injury compensation, says Gentry, who was consulted on drafting the bills.

The Vaccine Injury Compensation Modernization Act of 2021 (HR 3655) would allow vaccines recommended for adults—not just children or pregnant women—to be added to VICP. It would also increase the statute of limitations from three to five years, shorten the time required to decide cases, increase the number of special masters, and raise the maximum compensation for death or “pain and suffering and emotional distress” to $600,000 with annual inflation adjustments.

Meanwhile, the Vaccine Access Improvement Act of 2021 (HR 3656) would expedite the addition of new vaccines to VICP—including COVID-19 vaccines—by automatically adding an excise tax to vaccines when the CDC recommends them and shortening the time the HHS Secretary has to add them to VICP. Senator. Bob Casey (Penn.) is sponsoring the Senate companion bill (S. 3087).

“Significant delays up to two years have previously stalled the addition of new vaccines to the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program,” Doggett says, and automating the excise tax process resolves that problem for COVID-19 vaccines and future ones.

However, Salmon and other experts are skeptical that Congress has the stomach for reform. There’s long been historical tension between giving the vaccine court the attention, resources, and support it needs without giving legitimacy to vaccine injury conspiracy theories, says Jason Schwartz, an associate professor of public health at Yale.

“The existence of the program is often used as sort of ammunition by critics of vaccine safety,” he says. That’s especially concerning now that vaccines are a partisan issue: Polls show greater vaccine hesitancy and refusal among Republicans, and more Republican legislators support bills against vaccine mandates.

“The anti-vaccine movement, which now has political power that it never had before, would very much want to make it easier to sue pharmaceutical companies” and to eliminate the vaccine court entirely, says David Gorski, a surgical oncologist who has blogged about the anti-vaccine movement for nearly two decades.

The moral dilemma of vaccine mandates

Aside from vaccination as a public good, there’s another reason bioethicists urge compensating generously for COVID-19 vaccine injuries: Not since the smallpox vaccine have widespread mandates required adult vaccination outside a healthcare or military setting.

Cody Robinson, a 36-year-old stuntman from Atlanta, has won awards for some of his two dozen film credits. After having COVID-19 last July, Robinson didn’t see a reason to get vaccinated right away, but the Screen Actors Guild began allowing productions to require vaccines on set.

After losing several jobs worth more than $40,000 in wages, he felt “strong-armed” by his industry. “It became clear to me that the message in the industry was, if you don’t get vaccinated, you ain’t working,” he says.

Like McFadden, Robinson developed multiple blood clots after his J&J jab, including one in his jugular vein. Now, despite having encouraged his mom to get vaccinated, he feels disillusioned. Since he can’t do stunts while taking blood thinners, he’s losing more money now than before—and more than CICP’s wage cap of $50,000. “If the government’s going to force you to do something, they should provide compensation if they’re screwing you over,” he says.

Vaccine mandates raise the government’s moral obligation to generously compensate people harmed by vaccines, Caplan says. At the very least, Schwartz adds, “we should treat COVID-19 vaccines the same way we treat all vaccines that we recommend or mandate.” Without Doggett’s and Casey’s bill passing, that only happens if Congress passes the excise tax on COVID-19 vaccines. No imminent action is expected, according to a Senate Democratic aide, but the aide said it's an important issue that Congress members will be working toward in the weeks and months ahead.

Meanwhile, the experiences of Ekanayake, McFadden, Giovanni, Depaula and Robinson have colored their attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines.

Despite wanting to vaccinate Aiden’s younger siblings, Emily Ekanayake hasn’t done so in case there’s risk of a genetic component. McFadden isn’t filing a CICP claim for now, lest it exclude her from collecting VICP compensation later. Giovanni worries about her son’s future while she considers filing for bankruptcy. The rest of Depaula’s family aren’t comfortable getting vaccinated. And Robinson has become more outspoken in opposing vaccine mandates. Though they all recognize the importance of COVID-19 vaccination, they also feel betrayed and sidelined by the government when they did what their president asked them to.

“They hung me out to dry,” Ekanayake says. “I trusted them. I did what they said, and then you get a vaccine injury, and they’re like, I’m sorry.” Fixing the program and ensuring her family receives compensation, she asserts, would at least make her feel as though there’s accountability and a genuine belief that “we’re all in this together.”

Kendrick Brinson has worked full-time as a staff photographer for newspapers for four years after receiving a journalism degree from the University of Georgia in 2005. She has lectured and led workshops about long-term documentary projects, staying passionate about photography, and the business of photography at The Atlanta Photojournalism Seminar, Western Kentucky University, Ohio University, ASMP, University of Miami and several others.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

-

How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

-

This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

-

Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

-

When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

-

Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

-

Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

-

The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

-

This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

-

Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

-

Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

-

Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

-

Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

-

Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

-

Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

-

Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

-

NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

-

Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

-

Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

-

What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico