Stress

How to Confront

Expert advice for blowing off steam without burning a bridge.

Posted June 27, 2014

Iakov Filimonov/Shutterstock

Do you confront people? If so, how? I was recently asked to share some thoughts for an article by Vivian Manning-Schaffel, but the site seeking the piece is now defunct. But I say we confront the adversity by letting the interview live on. Below I present Vivian's questions and my answers, finding a new home here:

VM-S: Confrontation is seldom easy or fun. But sometimes, it’s unavoidable. Why do we make excuses to avoid confrontation?

RH: That's a good motivation question. Most theories of motivation are a re-branding of the "seek pleasure/avoid pain" staple. In the case of avoiding confrontation, it's safe to say it's about avoiding some potential pain. For example:

- Fear of loss. Some fear that the confrontation will result in the other person leaving or determining that you are too high-maintenance to deal with. The counter-argument would say that if someone splits because of a simple confrontation, they weren't invested in the relationship in the first place. Good riddance.

- Fear of causing pain. Some believe the other person is too fragile to handle being confronted, so they avoid the conflict in an effort to protect the other. But many times, they are more resilient than you give them credit for, and your failure to confront just builds a wall between you.

- Fear of strain. Confrontation can be physically stressful—your muscles tense, your pulse rises, the adrenaline starts to flow—so some actually avoid the physical sensations that accompany it. But think about it: Is it really that bad? Aren’t you voluntarily raising that stress when you work out?

- Fear of failure. You might raise your point only to see it shot down. Maybe you are off base, and a confrontation will bring that into the light. But this can be avoided in how you phrase the confrontation. Using “I" language, for example, changes “You never do the dishes!” to “Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think I’ve done the dishes the past few times. Would you mind doing them this time?"

What’s the best way to go about getting something off of your chest if you’re nervous about clearing the air? What’s the best way to psyche yourself into it?

RH: For the pure psych up, I’d recommend focusing on the “honesty is the best policy” mantra. Relationships generally work better if all the cards are out on the table. It might get messy for a while, but if you stick to your point, back it up with evidence, are willing to take responsibility for your role in the conflict, and view winning as relational cohesion rather than an actual winner/loser outcome, it generally works in the long run.

I’ve heard two other sayings that help people psych themselves up. The first is, “Let people feel the weight of your words and deal with it.” This makes a confrontation a noble deed that, if avoided, is a disservice to the other. The other saying is, “He’s a big boy; he can take care of himself.” If you’re afraid of damaging the other with your opinion, this can help remind you of the other person’s resilience.

Overall, you need to know that getting something off your chest is better for you and your health in the long run. Psychological and medical research is filled with data supporting the idea that holding a grudge has negative long-term consequences. It’s better to endure five minutes of stress than months or years of resentment.

What’s the best reason to clear the air if your inclination is to sweep the issue under the rug? And what’s the best approach to take?

RH: The most important reason is the deep psychological one: You matter, your opinion matters, and having a voice is worth a little discomfort for you and those around you. For people who struggle with self-esteem concerns, this is a difficult challenge to embrace. For those with too much self-esteem, maybe you have the opposite problem of bulldozing others and not taking the time to listen. But here I'm speaking to the conflict-avoidant, and the truth is, sweeping things under the rug doesn’t work. Even if you are able to keep the complaint under wraps, you will likely seek other ways to relieve the stress or numb the pain—with food, medication (or drinking or drugs), passive aggression, or other means. Not confronting doesn't mean the problem goes away; it's just buried inside causing a host of physical, psychological, and relational problems. That's why I recommend you find a way to just say it.

Using "I"statements ("I feel ___ when you do ___, therefore I'd like ____") is often helpful, as you're talking about your experience and feelings rather than jumping into attack mode and putting the recipient on the defensive.

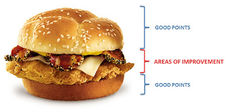

"Yummy sandwich. Fried food kills! Mmm, sesame seeds."

Some people also find the “sandwich approach” helpful.

In this technique, you sandwich a negative comment between two positive ones. Rather than, “I don’t like your taste in music,” you might say, “I love the fact you are such a fan of music; so am I. I wonder if we might listen to a wider variety to broaden our tastes, because I really like listening to music together and want to continue in the future.” It’s a little corny, but people are more open to the medicine when it’s wrapped in sugar. (This approach is not loved by everyone.)

Sometimes, you can’t help but experience residual bad feelings even after you’ve shared them, or even received an apology. Or maybe we’ve downplayed the true depth of our feelings and haven’t honestly expressed our emotions as we should have. What if you’ve already said you’re fine with a situation, and really thought you were, but then discover nagging feelings that indicate that you aren’t? What’s the healthiest course of action?

RH: I think you’ve got to say it again, but take responsibility for not saying everything correctly the first time. Confrontations are unpleasant for the other person, too, and this should be acknowledged. Say something like, “I know I brought this up before, and I hate to do it again, but I left a few things out. I meant to add ______. Thanks for hearing me out again, and I’ll try to include everything at once next time.” And then actually do this next time. If you want to keep an audience for your complaints, you owe it to them to get to the point.

Sandwich confrontations welcome at my website and facebook page. And while you're at it, come get a HeadCheck, the quick and easy mental health checkup.