When Vladimir Putin gave his first press conference since the Ukraine crisis began, he oddly said there were no Russian troops in Crimea—aside from those who were already stationed at a Russian Navy base.

The armed men outside administration buildings and airports are not Russian soldiers, Putin claimed—these are "self-organized local forces of volunteers."

Putin may be delusional—German Chancellor Angela Merkel recently remarked he had lost the plot—but he has a valid point. There are self-organized volunteers in Crimea.

Some have arrived via social media—one Web page, the Civil Defense of Ukraine ("Russian Get Up!") on Vkontakte, the Facebook of Russia, already has 7,000 followers. It encourages men, ages 18 to 45, to rush to the Crimea to defend Russian values.

But Serbian Chetniks, led by a former Kosovo war fighter named Milutin Malisic who brought a group of fighters to Crimea nicknamed "The Wolves," says there are other reasons: Serbs have a responsibility to their Orthodox brethren.

"We [represent the] Chetnik movement, and we can compare with the Cossacks in Russia," he said. "During the wars in Yugoslavia, a lot of volunteers fought on the Serbian side and we have decided to help them. It is our duty to be here."

Malisic added that he did not expect many Serbian fighters to join him. "We are a small nation," he said. "But we also cultivate a great love for Russia."

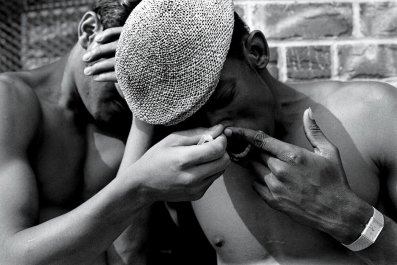

The Chetniks might be small in number but their presence in Crimea is still alarming. From 1992 to 1995, in the former Yugoslavia, the word Chetnik sparked instant terror in Bosnian Muslim and Croat civilians.

These fighters wore balaclava style ski masks instead of the traditional long beards and furry hats modeled after Russian Cossacks, but their names were synonymous with war crimes: rape, murder, ethnic cleansing and other hideous acts of atrocity.

They were a revival of Serb nationalists with roots that sprang from a monarchist paramilitary that formed a resistance force first against the Ottoman Empire in 1904.

The original Chetniks participated in the first Balkan war, and both World War I and II, where their conservative nationalism was directed not only against the German invader, but also the Communists, led by a Croat, Josip Broz Tito.

They came to the attention of the legendary British war hero, Fitzroy Maclean, who was sent into Yugoslavia during World War II by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to penetrate the guerrilla war and work with Tito and his partisans.

Part of Maclean's brief was to find out "who was killing the most Germans," regardless of political ideology or affiliation. It was believed to be royalists and their military arm, the Chetniks, led by General Draza Mihailovic.

Maclean and Churchill's focus was more directed toward Tito. Postwar, there was some regret about lost opportunities: that military aid had not been given to Mihailovic and his men, but instead was given to Tito and the Communists. (Maclean did eventually conclude that the partisans were killing even more Nazis than the Chetniks).

When Yugoslavia broke up after 1991, it was no great surprise that ultra-Serb nationalists went back to men they considered heroes—the Cossack-like Chetniks. But according to Tim Judah, an expert on Serbia, their appearance in Crimea was expected.

"Just as small numbers of Russians, Greeks and others came to help the Orthodox Bosnian Serbs during the Bosnian war, a handful of Serbs have now turned up to help their Russian brothers in Crimea," he said.

But he finds a strange irony in their mission. "They are self-proclaimed Chetniks, whose forebears in the Second World War both fought against and collaborated with the Nazis against Communist forces," he says. But their alliance is a "weird distortion of history," as the Russians claim they are against "fascist" Ukrainian Banderovts—who were Ukrainian nationalists and, just like the Chetniks, both resisted and collaborated with the Nazis against the Communists.

The British journalist Misha Glenny called the revival of the Serb nationalists in Yugoslavia in the 1990s one of the most "hideous and frightening aspects of the fall of communism in Serbia and Yugoslavia."

"This breed, which finds nurture in the perpetration of unspeakable acts of brutality, encapsulates all that is irrational and unacceptable in Balkan society," he wrote in his book The Fall of Yugoslavia.

At the time, Glenny observed that the thought pattern and actions of the nationalists were not "peculiar to Serbia, but only here have they been allowed to fulfill their sick potential with no barriers."

After the Kosovo War in 1999, the Chetniks laid low. But the Ukraine crisis has clearly sparked a common feeling of Slavic unity.

The Serbian press responded by saying there are only a limited number of Chetnik fighters in Crimea—five, to be exact—and that they were being used for minor jobs, such as manning checkpoints. They also questioned Malisic's background and motives.

"If the Russians did their homework, they will certainly beg the Chetniks not to help them," says Zoran Kusovac, who is based in Belgrade for Jane's Defense Weekly. He says the Chetniks are basically bandits.

"Wherever these pompous 'defenders,' with idiosyncratic headgear, appeared, the population they allegedly were there to protect disappeared for good," he says. "As did all video recorders, televisions, fridges, tractors and cars—regardless of their owners' ethnicity or creed—that were within reach of these bearded creatures."

Traditionally, Serb and Russian nationalists are closely aligned by their Orthodox Christian religion, their Slavic roots and their anti-Western perceptions.

In Tito's Yugoslavia, most school children were taught Russian as a second language; and when Yugoslavia disintegrated, Russia became the natural hiding place for war criminals and other disreputable Serbs—such as the much-loathed Mira Markovic, wife of former wartime President Slobodan Milosevic, who died in prison while defending himself against war-crime charges at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

Serbia has always been something of a foothold for Russia inside the Balkans, and the Russians have poured large amounts of money into the dire Serbian energy sector.

While other Europeans reacted with horror to Putin's interference in the Ukraine, in Belgrade, several thousand pro-Russia demonstrators took to the streets on March 3, holding placards reading: "Crimea is Russia and Kosovo is Serbia."

Officially, though, Serbia is playing it diplomatically. This year Serbia began talks to join the European Union and most young Serbs, when interviewed, say they would prefer to forget their pariah reputation and their past—the war crimes, the international isolation, the U.N. sanctions, the bombardment by NATO—and move on.

"Let's face it," said one young Belgrade-based graphic artist. "The future is in Europe. It's not here."