I’m autistic. While I face considerable challenges in life, I do like living, and I try hard to be okay with who I am. I wouldn’t want to turn non-autistic, because I wouldn’t be me anymore.

Autism is a difference. It comes with advantages and disadvantages. While every autistic person gets a different mix of traits, I’ve found that autism can enhance my focus on my interests and help me be more understanding of people who are different (among other things).

But that doesn’t preclude autism from being a disability.

Some writers, when reporting on the neurodiversity movement, claim that autistics think autism isn’t a disability. I believe that these writers are not only acting on a misconception of the autistic rights movement (which has long stated that autism is a disability), but acting on a misunderstanding of what disability means.

It’s okay not to understand disability. (Though, if you’re writing an article, you should really, uh, fact-check that stuff.) We’re all learning, and today you and I can explore this concept together.

Let’s talk about something called the “social model of disability.” Don’t know what it is? That’s okay!

The social model of disability

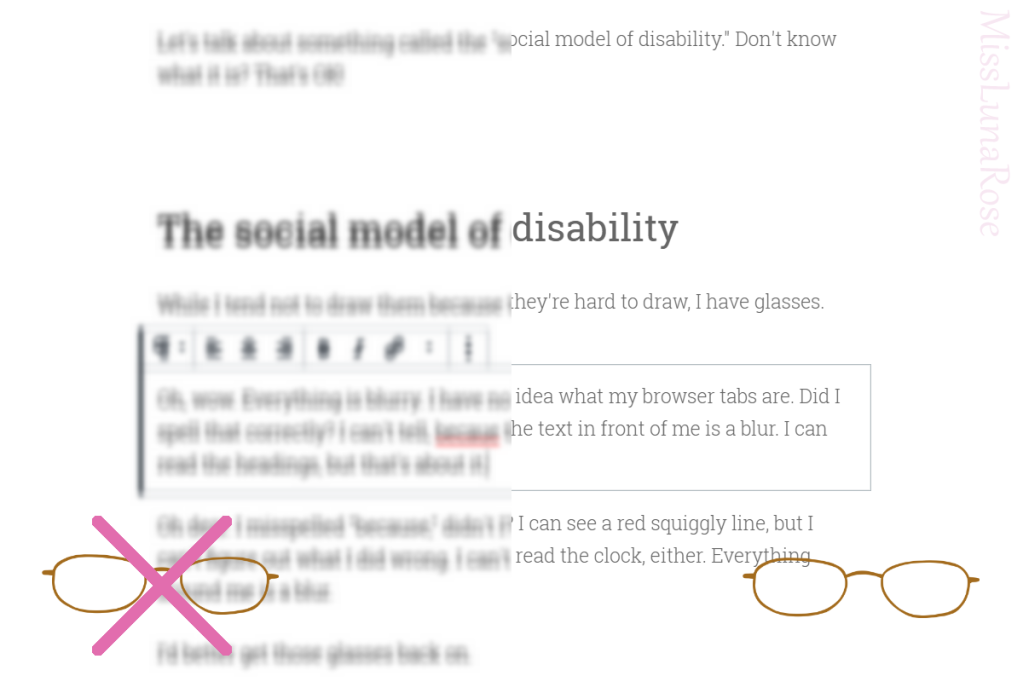

While I tend not to draw them because they’re hard to draw, I have glasses. Here, let me take them off.

Oh, wow. Everything is blurry. I have no idea what my browser tabs are. Did I spell that correctly? I can’t tell, becaue the text in front of me is a blur. I can read the headings, but that’s about it.

Oh dear. I misspelled “because,” didn’t I? I can see a red squiggly line, but I can’t figure out what I did wrong. I can’t read the clock, either. Everything around me is a blur.

I’d better get those glasses back on.

At last! The world is clear again.

As you can see from the diagram and the (gasp of horror) typo, my body lacks an ability that other people have. The world is full of people who can see things clearly without help. But all I see is a blur. My body is incapable of something that other people can do.

Does that mean I have a vision-related disability?

This is where the social model of disability comes in. I bet you were wondering!

According to the social model, people have a disability if…

- Their brain or body can’t do a certain thing, and

- Society does not accommodate that inability.

My nearsightedness meets criteria 1. My vision is objectively worse than average. (I blame library books.) I have an inability.

But it doesn’t meet criteria 2. Because as soon as I put on those glasses, the inability becomes irrelevant. My vision becomes 20/20. I can accomplish all my daily tasks without a problem. No employer would ever question my competence based on my glasses.

An inability becomes a disability only when society doesn’t properly accommodate it.

Autistic people lack accommodations. Thus, we’re disabled.

Don’t get me wrong: my school’s disability center provides some awesome accommodations. But they don’t erase all my struggles.

Here are some examples of ways I am disabled:

- Sports cars and motorcycles hurt my ears. I’ve missed class before due to pain caused by revving engines. Ear protections can reduce pain, but they also reduce my ability to hear conversations.

- Restaurants can be busy, with loud music and painful clanging dishware and too much going on. I’ve had to decline social opportunities because I know I won’t be able to cope with the environment.

- Websites with high contrast hurt my eyes and make it hard to read.

- I cannot have a “normal college experience” because the demands of my coursework exhaust me too much to go out with friends. If not for my accommodations, I couldn’t have a college experience at all. Sometimes I wonder about what I’m missing out on, but I remind myself that I need to avoid getting sick again.

I wouldn’t be disabled anymore if the world accommodated autism. If they invented autism-glasses that adjusted for all my difficulties, then I would be different but not disabled.

Boy, that sounds nice.

Why it matters

I really like the social model of disability. Because, according to the social model, my disability isn’t my fault.

I was born autistic. It just happened that way. I can’t control it. It’s not my fault that I’m unable to do certain things.

The problem is that the world isn’t designed for me.

The social model erases individual blame.

The social model of disability is used in contrast with the medical model. According to the medical model, disability exists because something is wrong with the brain or body.

So if we used the medical model of disability, we need to fix what’s “wrong” with the person. For example…

- Wanda finds it extremely painful to walk. She should either use medical equipment (a wheelchair) or go to physical therapy to help her walk. If that doesn’t work? Too bad, I guess.

- Dennis is deaf. He needs hearing aids or a cochlear implant to turn his hearing normal.

- Dylan is a teen with dyslexia. This is a deficit in his brain. He should go through intensive tutoring to catch up to his peers.

- Autumn is autistic. Since there is no cure, she should go through intense behavioral therapy to train her to stop acting in such strange ways.

Wow… Sounds exhausting.

Whereas if we use the social model, we start thinking about changes in society. The responsibility lies not on the person to change themselves, but on everyone to be inclusive.

- In addition to wheelchair use, Wanda needs curb cuts and functioning elevators. A building should have 2 elevators in case one of them needs maintenance, and wheelchair-accessible seating should be available at restaurants.

- Dennis needs subtitles on movies so he can enjoy them. Sign language interpreters can help him at events. Communication can involve sign language, writing, or texting, depending on what works for Dennis. Whether Dennis wants a hearing aid or cochlear implant is up to him.

- Dylan should be able to use audio versions of textbooks in order to learn material. He and his teachers should work out a plan so that he can learn without exhausting himself trying to read all the time.

- Autumn’s unusual-but-harmless behavior should be accepted by other people. Her school or workplace should talk with her about useful accommodations (like headphones and fidget tools) to help her feel comfortable.

None of these people have to feel defective. According to the social model, we’re not broken. We’re just different. Society should meet us halfway.

And if we start phrasing it as a mismatch between the world and a person, instead of a deficit in the person, we help disabled people feel OK with being disabled. Instead of saying “I’m broken,” someone can say “Society isn’t meeting my needs.”

And maybe “How can we change the environment so that I can succeed?”

We focus on changing the world.

If disability is caused by an inaccessible world, then how do we fix it? By making the world more accessible.

Society wasn’t given, fully designed and implemented, to the world from the hand of God. We created it. Disabilities were created when society designed itself to include the majority of people while ignoring the needs of the minority. What is and isn’t a disability could be different in a different society.

And that means we can change society to be more inclusive.

Some of this is happening already. I’ve seen a few initiatives to make autism not so much of a disability.

- A few stores are implementing “quiet hours” where they keep everything calmer so that autistics and people with sensory sensitivities can shop in peace.

- Neurodiversity at work programs are encouraging accommodations and getting rid of inaccessible hell-spaces such as “open offices.”

When the world accommodates autistic people, disability fades away.

Does the social model always work?

Hmm… It depends on your perspective. But I’m going to say no. I do think the medical model is useful for things that are actual illnesses.

Some conditions just… legitimately stink. For instance, anxiety. Anxiety does nothing but impede my life and make me more miserable. I like my anti-anxiety medication and will continue using it so that anxiety doesn’t have to hold me back. If there were a pill that could cure anxiety disorders forever, I would take it immediately, and I’d advocate to make sure everyone had access to it.

What is the difference between an illness (like anxiety) and a disability (like deafness or autism)? It’s in the eye of the beholder, I think. In my opinion, we should let the individual communities speak about it and define it themselves.

Yes, I want an anxiety cure. Yes, I want a depression cure. These are illnesses that I acquired and I want them to go away, please.

But I don’t want an autism cure. Autism is a difference I was born with, and it shapes who I am. I wouldn’t be me without it. Instead of a cure, I want society to change so that autistics are included and supported. Since this hasn’t happened yet, I intend to help make it happen.

Maybe you can help make it happen with me.

Let’s review!

In case you haven’t noticed, I like doing a summary of main points at the end, in case any of you are scatterbrained and in need of a review.

- Autism is a disability.

- Under the social model, disability is defined by (1) inability, and (2) society not accommodating that inability.

- Thus, a nearsighted person whose glasses fix their vision is not disabled. Whereas a blind person, who might find their surroundings inaccessible, is disabled.

- It’s not our fault that we’re disabled.

- Disabled people need accommodations, not a “cure” or intensive therapy. We’re not sick. (Though actual sicknesses, of course, do exist and do need treatment.)

- By making the world a more inclusive place, we can reduce disability, and maybe even someday erase it.

I hope this helped you understand disability, the social model, and what disability means to the autism rights movement. Disability isn’t a defect or a curse, and we don’t need to waste time feeling bad about it.

Instead, we’re going to go out there and try to change the world.