Tunisia one year on: Where the Arab Spring started

-

Published

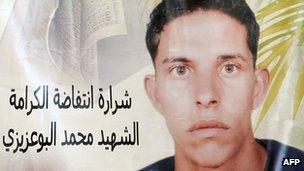

The man who lit the touch-paper of revolt in North Africa exactly a year ago was no fiery revolutionary. Mohamed Bouazizi was a young fruit and vegetable seller, supporting eight people on less than $150 (£100) a month.

His ambition was to trade up from a wheelbarrow to a pick-up truck.

"On that day Mohamed left home to go and sell his goods as usual," said his sister Samya.

"But when he put them on sale, three inspectors from the council asked him for bribes. Mohamed refused to pay."

"They seized his goods and put them in their car. They tried to grab his scales but Mohamed refused to give them up, so they beat him," she said.

Whether he was also insulted and spat at by a female official is disputed, but something snapped inside the 26-year old grocer.

He went to the governor's office to ask for his goods back; the governor would not see him.

So he acquired a can of petrol, poured it over himself and lit a match.

'Wave of sympathy'

Mohamed Bouazizi was rushed to hospital in a coma with 90% burns, but his act of desperation brought angry crowds onto the streets.

There was something about his helplessness in the face of corrupt officialdom, rising prices and lack of opportunities that triggered a wave of sympathy.

Faced with brutal security forces, the protesters did not back down, they grew bolder.

When Bouazizi died of his wounds on 5 January the rioting intensified. Hundreds were killed, hundreds more arrested.

Tunisia's President Ben Ali, a military autocrat in power for 23 years, went on television to appeal for calm.

"Unemployment was a global problem," he said.

He blamed the violence on masked gangs, calling them "terrorists".

Like so many rulers in the Arab world, Tunisia's president saw himself as a bulwark against Islamic extremism.

He believed that alone gave him carte blanche to crush anything approaching democracy.

But he under-estimated the depth of resentment his people felt at the cronyism, the corruption, economic hardship and simple bad governance.

Eulogised

Just nine days after the death of the street vendor, Tunisians heard the prime minister announce that the president was "unable to carry out his duties".

In fact he had fled abruptly with his family, trying first to escape to France, which refused to let his plane land, then to Saudi Arabia, which granted him asylum if he gave up all political activities.

The rule of President Ben Ali was over, triggered on the face of it, by the suicidal actions of a frustrated grocer.

If Mohamed Bouazizi had never lived then something else would almost certainly have set off the so-called "Arab Spring" - this eruption had been building for decades.

But across the Arab world and beyond, his name and that of his country, is now eulogised in poems, in speeches, in songs.

The mould of unquestioned dictatorship had been broken forever.