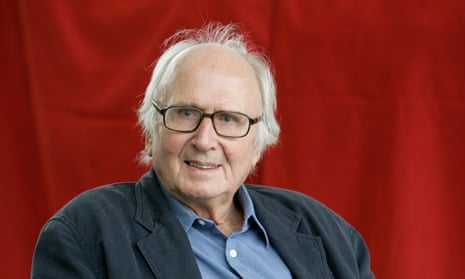

Through much of his life Nicholas Mosley, who has died aged 93, had to live down the notorious reputation of his father, the British fascist leader of the 1930s, Sir Oswald Mosley. Yet he managed to carve out a career for himself as a much discussed novelist and biographer. His often dense fiction caused one of his publishers to write: “I may not wholly understand this work but I recognise good writing when I see it,” and attracted film-makers, including Joseph Losey, who turned Mosley’s 1965 novel, Accident, into an intelligent and memorable film starring Dirk Bogarde.

Impossible Object (1968), which one critic likened to a crossword puzzle and which was filmed by John Frankenheimer as Story of a Love Story (1973), was shortlisted for the first Booker prize, in 1969. A later novel, Hopeful Monsters, the fifth part of the Catastrophe Practice series, became the Whitbread book of the year in 1990.

He also proved an adept biographer whose subjects ranged from the first world war poet Julian Grenfell (a relation of his first wife, who inherited the Grenfell papers) to the revolutionary Russian leader Leon Trotsky. But much of Mosley’s life was inextricably entwined with that of his father.

To be a son of one of the most reviled British politicians of the century might have been an unbearable Oedipal burden. Part of his personal achievement was to defy that inheritance, by writing a fair-minded, two-volume study of his father, published in the 80s, and later a revealing memoir, Time at War (2006), about his own active service with the allies while his father and stepmother were interned in Holloway prison.

At the time of Nicholas’s birth, in London, his father was a brilliant if mercurial MP still in his 20s, at that stage an independent, briefly a Conservative, and soon to join the Labour party. His mother, Cynthia, known as Cimmie, was the middle daughter of George Curzon, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, the foreign secretary in Baldwin’s government and the former viceroy of India. At the 1924 general election, both were elected Labour MPs: Oswald for Smethwick, Cimmie for Stoke-on-Trent.

Nicholas was nine when his mother died from peritonitis. His father, who had inherited the Mosley baronetcy in 1928, had a reputation as a womaniser, whose liaisons included one with Cimmie’s younger sister, Alexandra. At the same time he was seeing one of the Mitford sisters, Diana, who was in the process of divorcing her first husband, Bryan Guinness. For Nicholas, who knew Alexandra as Auntie Baba, his father’s promiscuity was confusing. On one occasion when, without Nicholas knowing, his father had taken Baba away on holiday, Diana slept in Baba’s room. Nicholas, used to paying his aunt a morning visit before she got up, was stopped by Andrée, the housekeeper: “It’s not Auntie Baba in there; it’s Mrs Guinness.”

By this time, Oswald’s politics had shifted unremittingly to the far right. Influenced by events in Germany, he had founded the British Union of Fascists. He and his followers aped the Nazi uniform by adopting black shirts. This led his son at school to be nicknamed “Baby Blackshirt”.

In 1938 it was only from newspaper headlines that Nicholas learned of his father’s remarriage, one reading: Hitler Was Sir Oswald’s Best Man. Oswald and Diana had married in Germany in Joseph Goebbels’s house two years previously, but had kept it secret even after the birth of their first son, Alexander. Nicholas chose to tell friends at Eton that it was a press invention. To his father he wrote that he was upset at the secrecy. “I am longing to have a talk with you about what you feel about Mummy and Diana.” Nicholas later recorded his father as saying that his second marriage was very good, but his first marriage had been perfect.

Nicholas developed a stammer as a child, not, as he once believed, as a response to his father’s “furious fluency”, but more as an antidote to his own aggression. He became a patient of Lionel Logue, the speech specialist who treated George VI (as recounted vividly in the film The King’s Speech). Logue did not cure his stammer, but the patient recalled that “he gave me confidence, he gave me hope”.

In 1940 Oswald and Diana were arrested and interned, and their children, including the newborn Max, were separated from them. Oswald had been expounding his belief that, if left alone, Hitler would ignore Britain and concentrate on defeating the Soviet Union. His son recalled that, at the time, he thought his father “a politician less lunatic than most”. But few others in Britain agreed, many viewing Oswald’s utterances as treasonable. In the Rifle Brigade, later during the second world war, on being introduced, Nicholas was often greeted: “Not any relation of that bastard?”

He proved a good leader, winning the Military Cross in the Italian campaign when leading his men in an attack on an enemy-held farmhouse. He also adored the camaraderie and egalitarianism of being a soldier. For the first time, he felt he was being judged on his own merit, and that set him free.

Nicholas was demobbed early as he had a scholarship awaiting him from Balliol. He decided to read philosophy, but was disappointed to find that in Oxford in the 40s philosophy was historical, meaning Descartes, Hume and Kant. He stayed at Oxford for just a year, feeling that he would have to work things out for himself. There he courted Rosemary Salmond, who was “someone who seemed to be in tune with my feeling that it was the world that was half over the edge, but that she and I might be able to hang on by my fingertips”.

After their marriage in 1947, they lived first in north Wales, where Mosley used £5,000 saved from a Curzon family trust to buy a small hill farm. His father, too, was farming, in more gentlemanly fashion, in Wiltshire. Their relationship remained good so long as he remained a farmer. But for neither of them was the land a long-term answer.

While his father yearned for politics and formed the Union party in 1948, Mosley wished to concentrate on writing. His first novel, Spaces in the Dark (1951), was influenced by what he saw as the madness of the outside world and the threat of a new, now nuclear war. It was accepted for publication by the young firm of Rupert Hart-Davis on the recommendation of David Garnett, who surprised Mosley by asking him if he wished to publish it under his own name.

His father did not talk about Mosley’s novels, let alone read them. Novels were, in his view, a waste of what might be a talent for polemic and rhetoric: “It is like entering a horse for the pony races at Northolt instead of the Derby.”

Nicholas himself wrote of his fiction: “I’ve always written novels to explain the way I saw life to myself, and I’ve always tried to write about the way people actually experience life.” If this was too philosophical for some critics, it helped explain why in 1991 he quit as a Man Booker prize judge after his fellow judges, who included the novelist Penelope Fitzgerald, refused to put his favourite, Allan Massie’s The Sins of the Fathers, on the shortlist. He also complained that all the other novels under consideration lacked ideas. Ben Okri won, with The Famished Road.

Mosley’s fiction was never an easy sell. When what he himself called “an almost unpublishable book” consisting, bizarrely, of four essays, three plays entitled Plays for Not Acting and a short novel, Cypher, was turned down by his regular publishers it was no surprise. Then Tom Rosenthal, a north London neighbour who ran Secker & Warburg, made him a proposition. He would publish the book, Catastrophe Practice, a reference to the catastrophe theory of evolution, which was challenging Darwinism. But he would do so on condition that Mosley wrote a biography of his father.

In the 50s he entered a religious phase influenced by Father Raymond Raynes, superior of the Anglican Community of the Resurrection. In 1961 he wrote a biography of Raynes. He followed it with Experience and Religion: A Lay Essay in Theology (1964). Although he did not use the title, in 1966 he succeeded to the Ravensdale barony on the death of his aunt Irene.

His relationship with his father had one final twist. Whereas in the 30s Nicholas had been too young to understand the minutiae of his father’s political beliefs, by the 50s they now found themselves at loggerheads. The Notting Hill race riots of 1958 led Oswald to stand as a Union party candidate at the 1959 general election, determined to attract the “keep Britain white” vote and deter immigration from the Caribbean. When Nicholas engineered what he called a “decisively antagonistic confrontation”, his father’s response was to say that he would never speak to his son again. That situation lasted for several years.

However, at the end of Oswald’s life, when he had Parkinson’s disease and had finally quit politics, they were reconciled. A week before his death in 1980, he decided his son should be his biographer, with access to all the Mosley papers. Nicholas knew that his father believed he would tell the truth as he saw it. The two volumes of biography were published as The Rules of the Game (1982) and Beyond the Pale (1983). Following Oswald’s death, Nicholas also inherited his baronetcy.

An editor choosing photographs with Mosley for his wartime memoir recalls how he giggled on spotting one of his father giving a speech and promptly did an off-the-cuff impression of all the arm-waving and braggadocio. Somehow he seemed to have found a way to admire and love him as a father, without sharing his views or excusing his faults.

His marriage to Rosemary ended in divorce in 1974. He then married Verity Bailey, who survives him, as does their son, Marius, and the children from his first marriage, Ivo, Robert, and Clare, his stepson, Jonathan, 19 grandchildren, 10 great-grandchildren and his brother, Max. Another son by Rosemary, Shaun, died in 2009.

Nicholas Mosley, Lord Ravensdale, writer, born 25 June 1923; died 28 February 2017

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion