Published January 25, 2012

Your [Noun] Looks So [Adjective]!

The Anatomy of a Compliment and Art of Giving One

Compliments are ubiquitous conversation devices; we give and receive them every day. But what ingredients must a statement contain to be classed as one, and—more importantly—is there a recipe for the perfect compliment?

Over Before it Began

The brunette at the bar feels the presence of a man move into her personal space. Proximity alert; start the countdown. 5…4…3… ‘So what you drinking?’ the stranger asks. ‘Sorry?’ she says. The guy grins inanely. ‘Don’t know that one! Is it nice?’

She starts her next answer with an ‘umm’ but he’s already speaking again. ‘Your hair looks really nice.’ She hears him this time.

‘Oh, thanks,’ she says, while forcing a one-sided smile, ‘I kind of hate it. The hairdresser totally ignored what I asked for’. Before he gets another chance to speak, the woman purses her lips and raises her eyebrows in that ‘Anyway, best be off!’ kind of way.

The man watches her walk back to her friends while he crushes the ice in his drink with his straw and taps his foot slightly behind the tempo of the music.

***

Mr Hopeful tried to oil the social wheels by using a compliment in his fleeting conversation at the bar, yet it instantly morphed him into Mr Hopeless. Why should a compliment, a seemingly positive statement of recognition, have such a negative effect? And could the man have reframed the compliment in a way that splashed the oil in the right places and got the wheels of interaction turning? The answers, it seems, lie in the study of human discourse.

The Science of Saying Something Nice

Researchers have been studying the ways humans use words for decades and it turns out language couldn’t play a more central role in our highly-social lives.

[We] form, develop, and dissolve relationships through talk; we express personality, give social support, indicate power, demonstrate interdependence, persuade, cajole, quarrel, invite, reject, divorce, propose, proposition, and propitiate primarily in talk.

— S. Duck, Meaningful relationships: Talking, sense, and relating.

One of the most interesting areas of inquiry into human language must surely be compliment behaviour. It sounds like such a simple idea: Person A says something nice to Person B about Person B. But in reality, compliments can be incredibly complex conversation devices. To show you what I mean, let’s undress the compliment from the bar to see what it looks like naked.

Linguists love categorizing things and, by analyzing thousands of nice things people say to each other, they’ve developed three ways of easily pigeon-holing any given compliment. The first step in coding a compliment is working out if it’s formulaic or non-formulaic. You see, perhaps the most surprising thing about most compliments is how similar they are to one another—in fact, they’re downright unoriginal.

Two-thirds of all compliments [include] one of five adjectives: nice, good, beautiful, pretty, and great. In addition, two verbs (like and love) [occur] in 90% of compliments that contain a positive verb.[1]

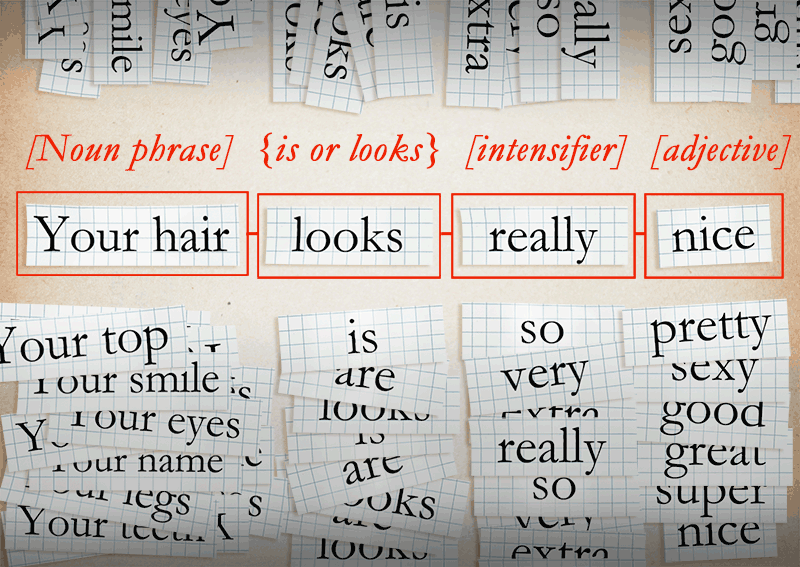

Most compliments not only contain similar words—they also employ common syntactic patterns. That is, they use the same sentence structures. Half of all compliments use this one[2]:

Take a second to think about that—50% of all compliments use the same four-part blueprint. You could take a quartet of words and shuffle them one-armed-bandit style to produce endless combinations of compliments using this single sentence structure, and that’s exactly what people do half of the time without even realising it.

So why are so many verbal pats-on-the-back plagiarized? The prevailing theory is that it isn’t so much a product of speaker laziness, but more a strategy for improving the recognisability of compliments. If the primary function of compliments is the ‘establishment or reaffirmation of common ground, mutuality [and] solidarity’[3] then it’s vital the recipient quickly recognizes the statement as being a compliment. If the positive statement goes right over his or her head, it fails to function as a compliment at all and its potential benefits (increasing social solidarity, triggering reciprocity, etc.) are lost. So the common syntactic structures of compliments, the most common of which you’ve just seen, act a bit like street signs: everyone shares an understanding of their meaning and knows how to respond when they’re faced with them.

The other two syntactic structures (which, including the first structure you’ve just seen, account for 85% of all formulaic compliments[3]) are as follows:

So, let’s get on with coding Mr Hopeless’ compliment using the first piece of criteria. Your hair is really nice. That’s a standard [Noun phrase] {is or looks} [intensifier] [adjective] right there, so it’s formulaic (which at least made recognizing it as a compliment easy for the woman at the bar, even if she didn’t seem to value it very much). Let’s move onto the next step in coding a compliment: the topic.

There are 8 different topic categories a compliment in the wild can fall under. They are:

Mr Hopeless’ compliment topic, because it made reference to the brunette’s nice hair, gets coded as appearance. That’s sort of unsurprising, as the majority of compliments use the appearance and attire topics, with performance, personality, and possessions accounting for most of the rest.[3]

An interesting bonus fact here is that women compliment each other on appearance more than any other topic, whereas men usually swap compliments about their possessions.[4] So in a sense, both genders live up to their evolutionary stereotypes.

The next coding criterion is whether the compliment is adjectival or verbal—this depends on whether the adjective or verb carries the positive evaluation. So, for example, an adjectival compliment might be “Your singing was really good!” because the positive evaluation is focused on the singing (the adjective). The verbal equivalent would shift the focus onto the person giving the compliment: “I really loved your singing!”[5]

Interestingly, women are much more likely to use a personal compliment (‘I love your shoes’) than men (who are more likely to say ‘Those are nice shoes’). Only 20% of women’s compliments are impersonal, whereas men take the impersonal route 60% of the time, especially when complimenting other guys.[6]

Mr Hopeless opted for an impersonal, adjectival structure when he said that the woman possessed nice hair, instead of specifying that he liked or loved it. So, the complete coding for his ‘Your hair is really nice’ line is that it was a formulaic, appearance-based, adjectival (impersonal) compliment. Now you know! But it doesn’t end there.

There are two sides to every compliment, the giver’s and the receiver’s, and linguists don’t disappoint when it comes to categorizing things for both parties.

When someone recognizes a statement as being a compliment that’s aimed at them, there are a dozen ways in which they can respond. They are:

In unconsciously choosing how they react to a compliment, a person has to walk a thin line between allowing social solidarity to be created or maintained (by acknowledging the compliment as true or meaningful) and avoiding self-praise (by dampening the sentiment somewhat or putting a disclaimer on it). Most people have had the experience of giving a compliment, only to have it effectively thrown back in their face by the recipient totally disagreeing with it—Mr. Hopeless is one of those unlucky people—and it doesn’t feel good. In fact, if a person unwittingly chooses the incorrect response to a compliment, social distance (instead of social solidarity) can be created.

The woman at the bar’s response was “Oh, thanks [appreciation token]. I kind of hate it[disagreement]. The hairdresser totally ignored what I asked for [reassignment].” If her walking away a moment later wasn’t enough to demonstrate that the compliment fell through the cracks into social oblivion, then this deconstruction of her response surely is. She couldn’t have said much more to downplay the whole thing. And why might she want to minimize the force of the compliment? One likely and common reason is that she didn’t want to enter into the unspoken social contract an embraced compliment can create between the giver and the receiver. She didn’t want solidarity at that moment; she preferred to maintain social distance instead.

As long as you don’t let it invade your social life too much, it can be a fun game to listen out for compliments and code them, and their responses, using the above system. You quickly see trends appearing and you’ll notice that each person you meet or know will tend to have a ‘compliment style’ of their own. For instance, they might tend to use personal compliments (I think, I love) more than impersonal ones, or repeat the same words again and again (amazing, nice, really).

So, compliments tend to be predictable—they’re tools for minimizing social distance, maximizing solidarity, and they follow certain patterns to promote instant recognisability. Likewise, there are only a finite number of ways in which a person can respond to a compliment and the method they choose will tend to reflect how they feel about the giver of the compliment, the topic of the compliment and themselves. With all that in mind, is it possible that an ideal combination of the compliment coding criteria exists? Is there a Goldilocks-style ‘just right’ mix of the topic, formulaic/non-formulaic and personal/impersonal ingredients that elicits the best feeling from the recipient every time?

The Art of Giving Compliments

Using what we’ve covered about the coding of compliments as a base, I’m going to lay out some new criteria for how I think a compliment should be constructed and presented. The goal of any compliment, remember, is to create, maintain or improve the feeling of solidarity between the giver and receiver, so the following considerations have been devised to maximize the chance of that happening.

Consideration #1: Motive

People are surprisingly good at recognizing not only what others are saying (the explicit and implicit message behind their words), but also why they’re saying it. It’s like every time a person receives a compliment their brain runs an unconscious check on it: Why did they say that? What are they trying to achieve by saying it? The optimal conclusion you want a person to come to when you compliment them is that you have no ulterior motive, or at least not one that they could find unpalatable, and that the sentiment of what you’re saying aligns with the statement you’ve used to express it. For instance, if you want to tell someone you really like a new piece of clothing they’ve bought (and that’s all), but their response is ‘Oh, you want to borrow it?’ [Request interpretation] then you’ve probably botched the delivery of the compliment in some way. Your motive (genuinely expressing your approval of the object) got lost somewhere.

Consideration #2: Relevancy

Mr. Hopeless (do you think he’s getting fed up of being called that yet?) used a compliment whose topic was pretty much entirely arbitrary. In other words, it’s very unlikely the woman’s hair was so remarkable that it deserved direct attention right there and then; hence it was difficult for the woman to see the compliment as being relevant to the moment in time it left the man’s lips. And, when a compliment isn’t relevant it isn’t spontaneous (an impulsive reaction to a thought or feeling). A lack of spontaneity hints at hidden motives too (the man simply wanted the woman to feel nice, to like him more), which is a contradiction of the first consideration.

When a compliment is interpreted by its recipient as being a method of achieving a social result they aren’t interested in or primed for, they are liable to reject or deflect it.

That leads neatly onto the next point.

Consideration #3: Receptivity

This is perhaps the most important thing you can consider when paying a compliment: how primed for receiving and enjoying the compliment is the recipient? The woman at the bar wasn’t primed at all; she had no reason to desire the verbal gift the man gave her. A lack of desire is like an absent appetite; there’s nothing to be fed, no void that craves to be filled. (As an aside: This is a mistake almost every single man makes when he’s trying to attract a woman. He tries to attract her before demonstrating that he’s attractive. This leaves all his work ahead of him, whereas if he had shown he was something special before indicating his interest, the attraction process would have been much easier, because the woman would have been craving his attention, instead of merely bearing it.)

The thing that most guarantees that someone is primed to receive and enjoy a compliment is if he/she feels positive about the person giving it and actually wants his/her approval, recognition and respect.

Consideration #4: Creativity

There’s absolutely a time and a place for formulaic compliments. As I explained earlier, they’re easily recognizable as what they are and they’ll usually get the job done just fine. For instance, if you’re eating at your partner’s parents’ house and they’ve cooked a meal and you say ‘This tastes great,’ the force and sentiment of that sentence will elicit the right kind of response from the host. There’s no need to make it non-formulaic and personal by saying ‘I’ve really enjoyed eating this meal and savouring its flavours’ (that is, unless you really need them to know the meal is exceptional). The compliment should match the desired response in strength and sentiment.

There are other times, however, especially when you’re complimenting your romantic partner (or a prospective one) that you are better off being more creative with your compliment construction and delivery. Intriguingly, studies show that compliments passed within sexual relationships tend to actually be less formulaic, probably because a deep, shared understanding of one another exists between partners[7]—compliment recognisability is less of an issue and the emotions tend to run deeper.

You can increase the positive impact of a compliment by presenting it more creatively (hinting at a fact or feeling instead of plainly stating it), which allows the recipient to feel like they’ve decoded the amazing meaning of what you’ve said, as opposed to having it shoved down their throat. For instance, imagine someone gives you a sweatshirt on Christmas morning. You could (and probably should) state how much you like it after it’s unwrapped, but a much more creative compliment would be to put it on several hours later and let them ‘accidentally’ see you in it. The latter statement, although non-verbal, communicates that you like it in a way that is much more likely to elicit positive emotion in the present-giver, because it’s a creative demonstration of your feelings.

Summary

It’s interesting and fun knowing how to code compliments. It can give you an insight into how people think and how they feel about you and themselves. However, I don’t recommend surreptitiously planning compliments in advance or double-checking that your responses to compliments fall under certain categories. That’s a recipe for disaster; you’ll probably end up showing an ulterior motive, sounding irrelevant and lacking the kind of spontaneous creativity that makes good compliments great.

It’s better to leave the really academic side of coding compliments for those social occasions where you find yourself bored and in need of some private entertainment, and during the other times—when you’re (hopefully) receiving compliments and dishing a few out yourself, simply aim to let your words and body language openly reflect the positive feelings that make compliments so…complimentary.

***

The brunette rejoins her friends, who part to allow her back into the group. She turns to face James, a work colleague she’s been dying to talk to privately all night.

“Well that was awkward,” she says, smiling.

“What?” James asks.

“Oh, just some guy at the…well…is my hair different tonight or something?”

James puts his drink down and conducts an exaggerated inspection of her head. He gently spins her around, saying nothing, only squinting, analyzing. She’s smiling like an idiot. “It looks all in order to me.”

He picks up his drink again while she whips her hair back into place. Surely he can feel that tension too. He starts to speak, “You know what I did notice…come in a little closer…” he motions for her to step forward towards him, “…what I did notice earlier…well, I thought I noticed…” he’s leaning forward now looking right into her eyes, “…is your eye make-up. You’ve started doing little flicks at the ends there with your eyeliner, right?”

That smile breaks out again across her face. “Well aren’t you Mr Observant!”

“So I’m right?”

“Yep, you got me.”

“Nice. I really like it. Like Cleopatra.”

A wave of excitement passes through her body as she tries to hide how happy James has just made her.