Training Your Brain to Improve Your Vision

A new game app had supernatural effects on athletes' eyesight. Brain training is coming for everyone.

Brain training is becoming big business. Everywhere you look, someone is talking about neuroplasticity and trying to train your brain. Soon there will be no wild brains left.

At the same time, everyone who spends more than two continuous hours using a computer is, according to the American Optometric Association, ruining their eyes with Computer Vision Syndrome. So, Dr. Aaron Seitz might be onto something with his new brain-training program that promises better vision.

UltimEyes is a game-based app that's sold as "fun and rewarding" as it improves your vision and "reverse[s] the effects of aging eyes." It doesn't claim to work on the eyes themselves, but on the brain cortex that processes vision—the part that takes blurry puzzle pieces from the eyes and arranges them into a sweet puzzle. (Brain training for memory, the kind we hear about the most on TV, would be the part that lacquers the finished puzzle, frames it, and hangs it on the wall.)

A standard 25-minute session using UltimEyes forces your eyes to work in ways they probably don't in everyday life, and its website warns that after the first use, "just like the first time that you go to the gym, your eyes may feel a bit tired. This experience typically goes away by your third session as your visual system adjusts to its new work-out routine."

Seitz is a neuroscientist at the University of California, Riverside. To test out his vision-training game, he had players on the university's baseball team use the app. Half the team trained for 30 sessions. For comparison, the other half did no training.

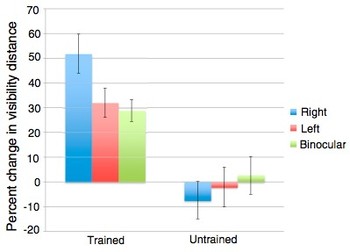

This week the peer-reviewd journal Current Biology published the results of those trials. Players who participated in the training enjoyed a 31 percent improvement in visual acuity. Seven players actually got down to 20/7.5 vision—they could read a line from 20 feet away that a normal person can only read from 7.5 feet away—which is very rare.

“Players reported seeing the ball better, greater peripheral vision and an ability to distinguish lower-contrast objects,” Seitz said.

That sort of thing has been shown in a lab before, but what makes this study especially interesting is that they also attempted to translate the effects of the training into baseball success.

"These results demonstrate real world transferable benefits of a vision-training program based on perceptual learning principles," Seitz and his team of researchers wrote in the journal. Using sabermetrics, the gaming system popularized by Bill James' statistical genius in 1980 and by Brad Pitt's medium-length hair in Moneyball in 2011, they found that the team on the whole scored 41 more runs than expected, and won five more games than they otherwise should have. The trained players had 4.4 percent fewer strikeouts after training, and the team on the whole saw greater-than-expected improvements in batting average, slugging percentage, on-base percentage, and walks, which the researchers imply—and the team's coach Doug Smith seems to believe—was due to the brain training.

"The improvements are substantial and significantly greater than that experienced by players in the rest of the league in the same year," Seitz said.

Here is the university's very interesting video recap of the study and its findings, which features psychologists talking over heavy metal music.

Dr. Peggy Series, a neuroscientist at the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved with the app or the study, told Popular Mechanics, "It's very exciting. The fact that the app is improving the players' visual acuity is not as surprising to me as that the improvement might actually help in playing baseball."

Dynamic visual acuity—the ability to discriminate the fine detail of moving objects—is known to be extremely important to baseball players, and better among players than nonplayers. Research has said that the baseball itself actually makes their vision better.

If you can't play baseball regularly and are cautiously optimistic about the promise of neuroplasticity, this app is a low-investment way to try out brain training. "We suggest that this approach has great potential to aid many individuals that rely on vision," the researchers write, referring there to a hefty segment of the population, "including not only athletes looking to optimize their visual skills, but also individuals with low vision engaged in everyday tasks."

Seitz fielded additional questions about the study yesterday on Reddit.