Loneliness

Treating Loneliness: It's More Than Just Meeting Others

Understanding the many different approaches to helping those who are lonely.

Posted April 30, 2014

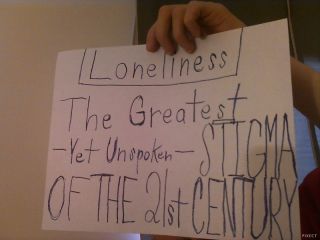

Loneliness: The Greatest Stigma of the 21 Century

Noted British TV star, Esther Rantzen has often told her story about loneliness as she continues to raise awareness about how this issue affects seniors. Her story is like so many others who suffer from chronic loneliness, one in which she experiences rather harsh prejudice for admitting she feels lonely. In an article by The Express, she says that her friends told her she should have more pride and that given her popularity and family, there is no reason why she should feel lonely. The most common prejudice against those that feel lonely is that a chronically lonely person is a failure, because anyone who feels lonely should be able to just go out there and meet people. That brings me to the heart of this post, which is that sometimes getting over loneliness requires more than just getting out there and meeting people. For chronically lonely individuals, a lot more work is required and no one is a failure for feeling lonely. Telling a chronically lonely individual to just go out there and meet people, is like telling an obese person, to just eat healthier or telling a depressed person, to just cheer up. It is patronizing and it needs to stop.

So, how does one intervene with the lonely? The answer, I believe, hinges on just how lonely a person is. Several researchers make reference to two levels of loneliness: chronic and transient loneliness (for example, de Jong-Gierveld and Raadschelders, 1982; Duck, 1992). For individuals who are chronically lonely, their experience of loneliness is persistent, often extending a period of many years, occurring regardless of the situation, and whose cause is more internal to the person. People who experience chronic loneliness may experience varying levels of intensity of loneliness, but there is always an underlying feeling that loneliness is always present. Transient loneliness, on the other hand, is experienced for short periods of time, and is usually the result of a particular situation, such as a rainy day. What would be required to help someone with chronic loneliness would be different from what would be required to help someone with transient loneliness.

Two comprehensive sources of information about how to treat loneliness come from Rook (1984) and Masi, Chen, Hawkley, & Cacioppo (2010). Rook (1984) in her paper discusses three levels of approaches to helping individuals who feel lonely. These levels are: individual, group, and environmental approaches. Individual approaches include such things as: cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), psychodynamic therapies, and improving solitary skills. It is focused on therapeutic intervention at the individual level. Group approaches involve the use of groups as a format for helping to deal with a variety of causes of loneliness. These group approaches could be used for social skills training and support groups such as a bereavement group. Finally, environmental approaches look at approaches at the community level, such as community awareness programs and restructuring social settings. This effort by the mayor of Vancouver to use block parties to reduce social isolation is an example of an environmental approach. The other comprehensive work was done by Masi et al., (2010). They did a meta-analysis of 77 studies of loneliness intervention programs and suggested four approaches across them: 1. improving social skills; 2. enhancing social support; 3. increasing opportunities for social contact; and 4. addressing maladaptive social cognition. Out of the four approaches suggested, based on their meta-analysis, they concluded that addressing maladaptive social cognition through such therapies as CBT were the most effective in treating loneliness.

What these two sources suggest is that there are a number of ways of attempting to treat loneliness. Certainly for individuals who are more chronically lonely, individual or group approaches seem more appropriate, particularly the use of CBT. However, I am sure there are quite a number of readers who would say that they have been chronically lonely, tried therapy, and found it quite ineffective. There may be any number of reasons why previous therapy has been ineffective. I believe one of the core reasons is that since loneliness is not defined as a mental illness (at least according to the DSM-IV) therapists may not have had training on how to treat loneliness and/or recognize it as a legitimate issue to address separate from other related mental illnesses such as depression or social anxiety. Other reasons could include other such factors as a mismatch between therapist and client, and the effectiveness of a particular therapist. In any case, until there are more widespread, empirically-based treatment approaches to loneliness, the options that chronically lonely individuals have are limited. It is also clear that just getting out there and meeting people is not going to solve the problem for individuals who are chronically lonely.

On the flipside though, there are a number of programs that do attempt to facilitate social connections. One growing intervention approach in this regard is with the elderly and teaching them how to use the Internet to connect with others; see for example a meta-analysis by Choi, Kong, & Jung, (2012). Other interventions include the block parties mentioned earlier. These interventions are certainly appropriate for individuals who experience transient loneliness. In other words, getting out there and meeting others would probably work well for individuals who are capable of forming and sustaining deep, meaningful relationships, but simply lack the opportunity to do so. These types of environmental approaches afford the opportunity to allow others to connect. However, it is important to keep in mind that these environmental approaches would not work well for individuals who are chronically lonely. Without doing some internal groundwork to get them ready to form and sustain intimate relationships, providing them the opportunity to connect will be meaningless at the least, or even worse, terribly frustrating and depressing.

For more on loneliness, visit: http://www.webofloneliness.com

References:

Choi, M., Kong, S., & Jung, D. (2012). Computer and internet interventions for loneliness and depression in older adults: a meta-analysis. Healthcare Informatics Research, 18(3), 191–8.

de Jong-Gierveld, J., & Raadschelders, J. (1982). Types of loneliness. In L. A. Peplau. & D. Perlman, (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 105-119). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Duck, S. (1992). Human relations (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Masi, C. M., Chen, H.-Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). A Meta-Analysis of Interventions to Reduce Loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review : An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 1–48.

Rook, K. S. (1984). Promoting social bonding: Strategies for helping the lonely and socially isolated. American Psychologist, 39(12), 1389–1407.