Adolescence

When Parents Name-Call Their Adolescent

A hurtful name can damage the relationship and close off communication.

Posted November 30, 2015 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Sometimes, out of impatience, frustration, discouragement, anxiety, or anger with their adolescent, parents can let hard feelings dictate the language they use. Attacking the problem by attacking the young person, they can engage in name-calling to vent displeasure over what is or is not going on, to painful effect.

But why should this be painful? After all, just think of that old adage: “Sticks and stones can break my bones but words can never hurt me.” No. Any number of middle school students contending with social cruelty from peers will tell you that tormenting labels do most of the damage—whether they sting in the moment or stick around to stain your reputation later.

At this vulnerable age, for example, being labeled a “weirdo” or a "fatso" or a “sleaze” by other students is no laughing matter. The bad name one is called can be used to justify mistreatment one is given.

(Never underestimate the damage negative name-calling can do. I believe that in the extreme, many acts of abuse and hate crimes are justified by name-calling: "You're nothing but a ______! You deserve what you are getting!" Using a hate-name can trigger an act of violence.)

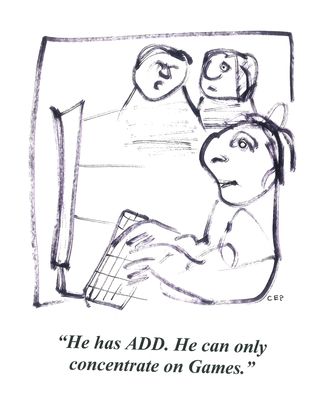

On a lesser scale, parental name-calling of their adolescent might include terms such as these: “slob,” “lazy,” “stupid,” “failure,” “loser,” “dumb,” “brainless,” “crazy,” “touchy,” “disappointment,” “waste,” “airhead,” “spacy,” “clumsy,” “ugly,” “thoughtless,” “selfish,” “irresponsible,” “wimp,” “screw-up,” "hopeless," “tramp,” “worthless,” “trash.” Name-calling is offensive because it is insulting, and is usually meant to be—whether from peer to peer at school, or from parent to teenager at home.

Of course, the teenager can act like these names don’t matter by blowing them off with a statement of bravado: “I don’t care what you think of me!” But that’s not usually true. Most teenagers I have seen, no matter how strained the relationship is at home, still want their parents' approval. “I don’t care” really means “I care too much to let my caring show.”

Parents remain the most powerful source of social approval in a teenager’s world, and they need to remain mindful of that. They also need to stay mindful of the harm name-calling their teenager can do. Consider a few possible unhappy consequences.

- Your emotions may be ruling your thinking and behavior.

- You may be blaming your adolescent for your lack of influence.

- Your language may be degenerating into words that attack self-esteem.

- You may be escalating tension in the relationship.

- You may be provoking the teenager into silence or defense.

- You may be reducing chance to specifically address the issues of concern.

- You may be modeling name-calling behavior that may come back at you.

- You may be defaming the whole person and ignoring many positive parts.

- Your term may be dooming the future by doubting the possibility for change.

- You may be using cutting words that can create long-lasting wounds.

- You may be affecting the adolescent’s view of self: “I’m as my parents say.”

- You may be alienating and estranging the relationship.

If, in the heat of the emotional moment, you ever find yourself name-calling or adversely labeling your adolescent, you might consider apologizing. After all, you wouldn’t like it if your teenager name-called you. “I’m sorry I called you a hurtful name. If you have something to say to me about how that felt I want to listen. And I won’t use that kind of language with you again.”

Then, ask yourself the operational question: “To what specific behaviors was I referring when I used that hurtful term? What was my teenager doing or not doing to which I was objecting?” Then proceed to state your concerns in more objective, non-evaluative words.

So, for example, having just accused your teenager of being “selfish” and “thoughtless,” stop and recast your communication by translating the names you called into behaviors of concern, then talk about these, and alternative conduct you would like instead. “You have twice now used my belongings without asking, and I need us to talk about changing that. If you would like to use something of mine, let’s discuss how you might ask me first.”

Of course, calling or referring to your adolescent as a “typical teenager” is usually not complimentary, so you might want to avoid that. Such stereotyping is prejudicial and not only insults the adolescent, but engenders a negative mindset in the parent: “What else can I expect?”

Name-calling your adolescent: very easy to get into, it’s worth the effort to stay out of even more.

For more information about parenting adolescents, see my book, Surviving Your Child's Adolescence (Wiley, 2013). Information here.