Wavy Greenland rock features 'are oldest fossils'

-

Published

Some of the world’s earliest life forms may have been captured in squiggles found in ancient rocks from Greenland.

The rocks were part of the seafloor 3.7 billion years ago, and the wavy lines, just a few centimetres across, would be remnants of primordial microbial colonies called stromatolites.

The evidence is presented in the academic journal Nature.

If confirmed, the colonies would predate the previously oldest known fossils by over 200 million years.

To put that in context, travelling back a similar time from today would be to leap into the world of the first dinosaurs.

But all claims of extremely early life are hotly contested, and this find is as well.

The find was made in a desolate expanse of uplands that butt up against the Greenland ice cap, called the Isua Supercrustal Belt.

The host rocks were exposed only recently after permanent snow cover melted.

The region is famous in geoscience because it is the oldest surviving piece of the Earth’s surface.

And in the late 1990s, Minik Rosing, a native Greenlander and professor of geology at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, identified chemical traces of life in its rocks – layers of carbon that had evidently once been part of living bacteria (although this interpretation has also been contested).

Prof Rosing suggests those bacteria lived in the surface of the ocean, capturing sunlight and photosynthesising, until they died and “rained down” to the seabed.

The layers of carbon are interleaved with volcanic ash that may have come from a nearby island.

The stromatolites described by Martin van Kranendonk and colleagues in this week’s issue of Nature would have lived in a quite different way.

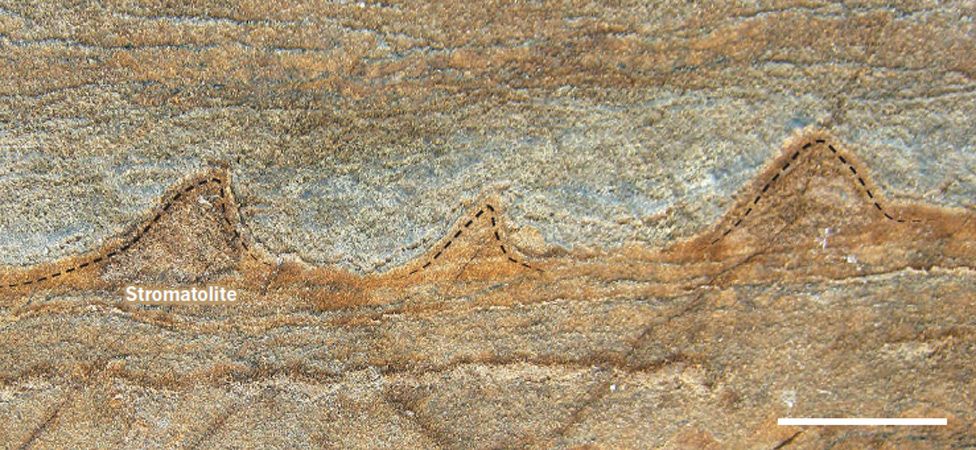

Stromatolites are effectively living rocks formed of mineral grains glued together by sticky, colonial bacteria.

They are rare today – the best known are in the harsh waters of Shark Bay, Western Australia, where bacteria slide up through each new layer of sediment washed up by the tides.

Similar mounds found in the Western Australian outback are currently the oldest acknowledged fossils on the planet, at 3.48 billion years old.

The older examples now claimed for Greenland appear to be remarkably similar, says Prof van Kranendonk, an early-Earth expert at the University of New South Wales.

“We see the original unaltered sedimentary layers, and we can see how the stromatolite structures grow up through the sedimentary layering. And we can see the characteristic dome and cone-shaped forms of modern stromatolites.”

The fossil structures are overlain by another thick layer of sediment – a sign the bacterial mats were fatally buried by mud or sand, perhaps during a storm.

“There’s plenty of evidence this was a shallow-water environment,” Prof van Kranendonk suggests.

“We can see the sands and rocks were moved around by energetic waves.”

The stromatolites themselves are limestone – precipitated out of the coastal waters by the original microorganisms, more evidence the researchers say that these are truly ancient.

There are no traces of the original microbes, only the mounds they built. But that is still incredibly important, says Prof van Kranendonk.

“This helps us think about how life developed on Earth, how fast that process was. It pushes everything back a little further, narrows the window between when we know nothing, and when we begin to know something.”

Prof Rosing, however, disagrees with almost every aspect of the analysis. The claim, he says, depends on the belief the samples come from a rare, well-preserved part of the original seabed. But since they were first part of the Earth’s surface, the Isua rocks have been twisted, stretched, crushed, and cooked by tectonic forces; the region is a geological “train-wreck” in the words of another geologist.

For example, Prof Rosing argues, the carbonate minerals far from being original biological precipitates, were produced far later, by reactions involving scalding soda water deep in the Earth’s crust.

The lines showing internal laminations, said to be primordial sedimentary layers, actually show where those waters percolated through the buried rocks. As for the dome- and cone-forms of the fossils, those are typical shapes seen where rocks of different strengths have been squeezed and stretched.

“It’s clear from the pictures in the paper that these are highly deformed rocks,” Prof Rosing told the BBC.

The problem is familiar in early Earth science – so much has happened to the rocks over geological history, it is hard to know what is original and what is an overprint by later processes.

Many claims of early fossils have fallen on close examination. Only a few survive the intense scrutiny of peer review.

Prof van Kranendonk stands by his argument that amidst the overall punishment suffered by the Greenland rocks, small pockets have survived well preserved – including the outcrop at the heart of this dispute.

“They’re just exceptional windows of preservation, which give us the keys to what happened so long ago.”

Geobiologist Michael Tice from Texas A&M University, US, who refereed the paper and approved its publication, takes a half-way position.

“The trouble with this kind of science is you’re trying to look at life after geology has done all the nastiest things to it. You’re limited by nature. The study is not definitive, but the evidence has passed all the tests they could apply.

"The point of publication is to stimulate more effort to find other examples.”

Prof Rosing agrees that a joint visit to examine the rocks in their original setting in Isua would be the best way to resolve the dispute. And Prof van Kranendonk hopes there may be further examples, older ones even, in the Greenland record.

What unites them is the belief that almost as far back as the rock record goes, life had already taken hold on the Earth. And the desire to know more about what that life was like.

Prof van Kranendonk can be heard discussing the new find on this week's Science In Action programme on the BBC World Service.