In the skies over Ukraine, one of the most dramatic fighter duels in decades is taking shape between an aging, but highly potent Western jet and one of Russia’s most advanced fighters: the battle of the F-16 Fighting Falcon vs. the Sukhoi Su-35.

This will be more than a clash of fighters. It will be a battle of philosophies between the Russian conception of fighters optimized for air combat, versus the Western conception of jets equally adept at air-to-air and air-to-ground combat.

It’s also a battle between old and new. The F-16s that Ukraine will receive were designed in the 1970s, though heavily upgraded over the years. Nonetheless, desperate to replace its dwindling fleet of Soviet-era Su-27 and MiG-29 fighters, Ukraine will be glad to receive 45 or more pre-owned F-16s from Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway, who are replacing their Falcons with F-35 stealth fighters. With Ukrainian pilots currently being trained in the U.S. and other nations, the first Ukrainian-piloted F-16s may fly this summer.

✈️ F-16 vs. Su-35: By the Numbers

The Su-35 made its combat debut during Russia’s 2016 intervention in Syria. But the war in Ukraine marks the Su-35’s real baptism of fire against an opponent equipped with modern fighters and anti-aircraft missiles.

Comparing the F-16 to the Su-35 isn’t easy. The F-16 is a fourth-generation aircraft that entered service in the late 1970s alongside the F-15 Eagle and the Soviet Su-27 and MiG-29. The Su-35 is considered part of generation 4.5, which are upgraded fourth-generation fighters that were introduced in the late 1990s, including the F/A-18 E/F Super Hornet, Typhoon, Rafale, and MiG-35.

“This is not a knock on the F-16,” Brynn Tannehill, a defense expert and former U.S. Navy aviator, tells Popular Mechanics, “but it was designed back in the 1970s.”

Either way, the stakes could not be higher. While American- and Russian-made fighters have been dueling since the Korean War in 1950, the upcoming clash in the skies over Ukraine will be vital. Russian airpower has performed poorly despite numerical and technological superiority in Ukraine, yet recent airstrikes using glide bombs have devastated Ukrainian defenses. To stop the Russian bombardment and launch a successful counteroffensive, Ukraine will need to at least contest control of the air, and ideally be able to launch airstrikes of its own.

// Viper and Flanker //

The F-16 Fighting Falcon (commonly known as the “Viper,” and occasionally as the “Lawn Dart”) was conceived out of embarrassment. During the Vietnam War, the world’s most powerful nation had failed to overwhelm North Vietnam’s small air force. One reason was that the U.S. military was using aircraft such as the F-4 Phantom—a powerful, but heavy fighter originally designed to intercept Soviet bombers rather than dogfight nimble MiGs.

This spurred a controversial group of innovators—the legendary “fighter mafia”—to convince the U.S. Air Force that it needed a small, lightweight, and relatively inexpensive fighter that could dogfight rather than rely on long-range air-to-air missiles as the F-4 had. The result was one of the most prolific modern jets, with more than 4,600 built since 1976, used by 25 nations and growing. It has also seen more combat than most current fighters, especially by the U.S. and Israeli air forces.

The Viper is about 50 feet long with a wingspan of 33 feet and weighs about 10 tons. It can reach a speed of Mach 2 (twice the speed of sound), is highly maneuverable, and is armed with a 20-mm cannon as well as 11 hardpoints to carry weapons and drop tanks, plus pods to jam radars and identify ground targets for precision-guided munitions. Its exact armament in Ukrainian hands will depend on what munitions the U.S. and Europe agree to send, but the F-16 is equally formidable in air-to-air and air-to-ground missions. In addition to medium-range AIM-120 radar-homing and AIM-9 Sidewinder heat-seeking missiles, it can carry JDAM glide bombs, HARM anti-radiation missiles, and probably long-range European missiles such as Britain’s Storm Shadow. The AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile, or AMRAAM, is particularly important. Unlike Ukraine’s current radar-guided air-to-air missiles, which require the launch aircraft to continuously maintain radar lock on the target, the AMRAAM has an onboard “fire and forget” radar that autonomously homes in on the target.

But versatility in all things means less capability at any one thing. “You can use the F-16 for air-to-air, but it’s not as good as an F-15,” Tannehill says. “You can use it for close-air support, but it’s not as good as an A-10. It can do ground attack, but it’s not as good as an F-15E Strike Eagle. … It’s a good aircraft at virtually everything, but it’s not the best at anything.”

The Su-35 also has a complicated history. It’s descended from the late-1970s Su-27 (NATO code name: “Flanker”), an air superiority aircraft designed for air-to-air combat. It was intended to be the Soviet answer to the F-15: just looking at the two twin-engine aircraft shows they have more in common than the F-15 has with the single-engine F-16.

The Su-35 was conceived in the early 1980s as a more maneuverable version of the Su-27 Flanker (hence the Su-35 is known as the “Flanker-E” or “Super Flanker”). After Sukhoi experimented with various prototypes under the Soviet and then Russian governments, the current Su-35 took shape in the early 2000s as an improved Su-27 with some air-to-ground capability that makes it more like fighter-bombers such as the F-16.

The Su-35 simply dwarfs the F-16. With a length of 72 feet and a wingspan of 50 feet, the Su-35 is about 50 percent larger than the F-16; at more than 18 tons, it’s almost twice the weight of the Viper. The Su-35 is armed with a 30-mm cannon as well as a dozen hardpoints capable of launching an array of air-to-air and air-to-ground ordnance. What particularly worries Ukraine and the West are its long-range R-37 and R-77 radar-homing air-to-air missiles, which are fire-and-forget weapons that can pick off Ukrainian aircraft from beyond the range of Ukrainian air-to-air missiles.

Complicating matters is the variety of aircraft involved. There are many variants of the half-century-old F-16, including various “blocks” of U.S. Air Force Vipers, as well as country-specific models for nations such as Israel. The latest version is the F-16 Block 70, with an APG-83 Advanced Electronically Scanned Array radar, an upgraded engine, and conformal fuel tanks.

But the Danish and Dutch F-16s pledged to Ukraine are Cold War models. They are F-16 MLU (Mid Life Update) models, which are European F-16A/Bs from the late 1970s that were upgraded in the mid-1990s with features such as an improved AN/APG-66(V)2 radar (an older non-AESA [Active Electronically Scanned Array] sensor), GPS navigation, and the capability to launch AIM-120 missiles. It is reasonable to assume that they are inferior to the latest Vipers, but far superior to Cold War-era F-16s.

“With the Mid-Life Update, what you’ve got to keep in mind is these aircraft have been continually upgraded with software that allow them to use modern weaponry,” Tannehill explains.

// The Su-35 Is More Maneuverable, But That Won’t Help //

Normally, a smaller vehicle is more maneuverable than a bigger vehicle. But for jet fighters, it isn’t that simple. There are a variety of technical factors, such as wing-loading (advantage: F-16) and thrust-to-weight ratio for quick acceleration (advantage: Su-35).

What is notable is that the Su-35 is considered “supermaneuverable,” in large part because it uses thrust-vectoring, which employs steerable nozzles to direct engine thrust. Using a capability found on only a few aircraft—including the F-22 and Su-30MKI—the Su-35 can perform the spectacular “Cobra maneuver,” where the fighter abruptly slows and stands on its tail, forcing an enemy aircraft behind to overshoot.

While impressive at air shows, the Cobra maneuver also deprives an aircraft of speed and energy, which is not a good thing in a dogfight. But the real problem is that while maneuverability was an issue in World War II or the Vietnam War, it is not a major factor in modern air combat. If today’s jets dogfight, it’s probably because one or both sides either made a mistake or lacked the technical capability for stand-off attack. The trend is for modern fighters, such as the F-35, to act as aerial snipers that stealthily pick off their prey with a long-range air-to-air missile that the target doesn’t even detect until it’s too late.

“What really matters is your radar, your reach, your [network] connectivity and how low-observable [stealthy] you are,” Tannehill says. “Radar determines when you see the other guy. Reach allows you to determine when you get to shoot. Low-observable allows you to push in closer.”

Indeed, this has been the pattern in the Russo-Ukrainian War. Fearing advanced surface-to-air missiles such as Russia’s S-400 and the U.S. Patriot, both Russian and Ukrainian aircraft have stayed on their respective sides of the front line, rather than penetrating enemy airspace. Even if the Su-35 really is supermaneuverable—which has yet to be proven in actual combat—the Ukraine war has not provided an opportunity to display it.

// The Su-35 Is the Better Sniper //

Unfortunately for Ukraine, the Su-35 is deadly at beyond-visual-range air combat as well as dogfighting. First, the Su-35 may spot the F-16 before the Viper spots the Flanker-E; the Su-35’s Irbis-E radar can reportedly detect airborne targets up to 400 kilometers (249 miles) away, according to its manufacturer, Tikhomirov.

The Irbis isn’t quite cutting-edge. It’s a passive electronically scanned array (PESA) system, which uses a single transmitter/receiver to emit a single beam on a single frequency through multiple antennas. This enables the radar beam to be electronically aimed at different directions without needing to mechanically rotate the antennas. That’s not as advanced as the AESA radars used on many Western fighters—including the latest F-16 Block 70 and Block 72 models—that use multiple transmitters to emit multiple signals at multiple frequencies simultaneously.

AESA radars can track multiple targets and are less susceptible to jamming. However, Ukraine isn’t getting AESA-equipped F-16s. The F-16 MLU’s AN/APG-66(V)2 radar is a gimballed pulse-doppler system with mechanically steered antennas that offer slower scanning on one frequency at a time. “Pulse-doppler screams ‘80s vintage,” Tannehill says.

In addition, the Su-35’s radar is more powerful. It has 5 kilowatts of power compared to just 770 watts for the AN/APG-66(V)2, Tannehill says. “I’m not saying that it can see five times farther or ten times farther, but it can see a lot farther than an APG-66.”

As if superior radar isn’t enough, the Su-35 has—on paper—better missiles. The R-37 has an estimated target-detection range of 400 kilometers (249 miles), while the R-77-1 has a range of 110 kilometers (68 miles). These “fire and forget” active-homing missiles streak to the vicinity of their target, and then use their own onboard radar to home in for the kill.

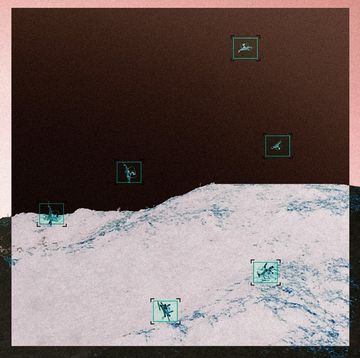

How effective these missiles are at such extreme ranges is questionable, but against Ukraine’s older jets, the Su-35 has been lethal. Su-35s and Su-30SMs, flying safely behind Russian lines at 30,000 feet, are locking on to Ukrainian jets with their Irbis radar, and then firing R-37 and R-77-1 missiles. Ukrainian fighters are armed with Soviet-era R-27 missiles with a range of around 50 miles. These early 1980s weapons use semi-active radar which requires the launch aircraft to continuously illuminate the target with a radar beam.

“Ukrainian pilots confirm that Russia’s Su-30SM and Su-35S completely outclass Ukrainian Air Force fighter aircraft on a technical level,” according to a November 2022 report by Britain’s Royal United Services Institute think tank. “Throughout the war, Russian fighters have frequently been able to achieve a radar lock and launch R-77-1 missiles at Ukrainian fighters from over 100 kilometers [62 miles] away. Even though such shots have a low probability of kill, they force Ukrainian pilots to go defensive or risk being hit while still far outside their own effective range, and a few such long-range shots found their mark.”

The U.S. has agreed to arm Ukraine’s F-16s with the AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile, first deployed in 1991. While the U.S. Air Force’s website lists the range of the AMRAAM as 20-plus miles, the latest AIM-120D is estimated to have a range of about 100 miles, which would outrange the R-77 but not the R-37. The Ukrainian government said in September 2023 that its AMRAAMs would have a range of around 160 to 180 kilometers (99 to 112 miles), which points to the AIM-120D.

// Our Verdict //

The outcome of a long-range missile duel between Flanker-E and Viper will depend on a lot of factors, including the quality of airborne jammers and decoys, how well these fighters are integrated into ground-based radars and missiles, and coordination between Su-35s and Russian A50 airborne radar aircraft.

And there are still other factors that may not become evident until combat is joined. Equipped with the NATO-standard Link 16 datalink, the F-16 probably has superior networking capability to the Su-35. That will make it easier for Vipers to coordinate with other air and ground platforms, including receiving early warning and targeting data from other sensors. While advanced Russian aircraft also have datalinks, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been plagued by unreliable communications systems and rigid command and control.

Even if outranged and outnumbered, Ukrainian F-16s could fly low to avoid radar detection amid ground clutter, and then use sensor data from other platforms to launch an AIM-120 at Russian aircraft. “The Russians may find out the hard way just how good datalink plus AMRAAM is,” Tannehill says.

Or, perhaps Ukrainian F-16s will try to avoid air combat whenever possible. Instead, they may be deemed more valuable as air-to-ground platforms, launching HARM anti-radiation missiles against Russian air defense radars, and cruise missiles and glide bombs against bridges, supply depots, and command posts.

For Russia, the threat posed by the Su-35 will keep the F-16s in check. The duel between two of the world’s most capable fighters may end in stalemate.

Michael Peck writes about defense and international security issues, as well as military history and wargaming. His work has appeared in Defense News, Foreign Policy Magazine, Politico, National Defense Magazine, The National Interest, Aerospace America and other publications. He holds an MA in Political Science from Rutgers University.