Neil Armstrong wasn’t sure he’d stick the landing. At 10:56 p.m. Eastern Time on July 20, 1969, as he made his giant leap for mankind, a range of possibilities floated in the astronaut’s mind. The lunar surface might be covered in a powdery dust, Apollo 11 scientists had warned him. That dust might ignite upon the landing. Or, as one astrophysicist predicted, the surface dust on the moon might be so deep that the lunar module—and the men inside—would immediately begin to sink, as if trapped in quicksand.

The United States had been preparing for a moon landing for the better part of a decade, ever since President John F. Kennedy had declared space exploration a national priority. But no one on Earth quite understood the moon’s geology. Telescopes offered limited insights. Earlier U.S. probes had mapped the moon’s surface but until that day, no human had gotten within nine miles of our only satellite. The only way to answer science’s most pressing questions was to set foot on the moon, no matter the risk.

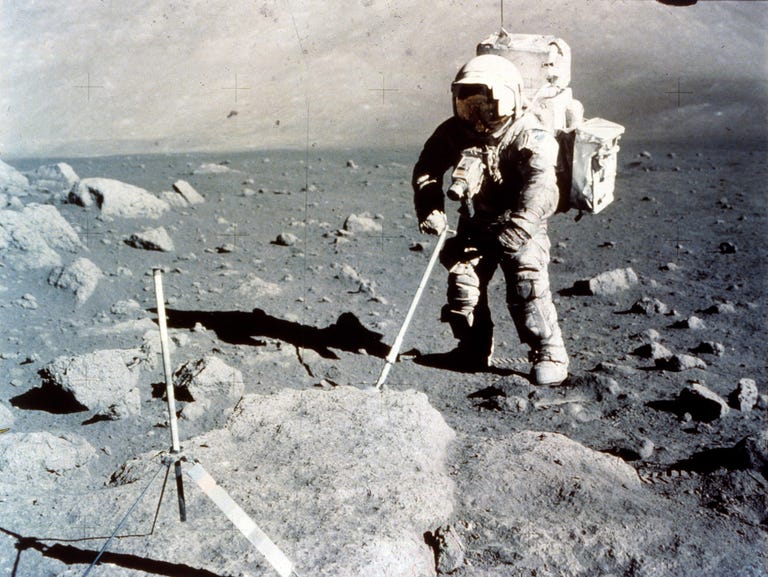

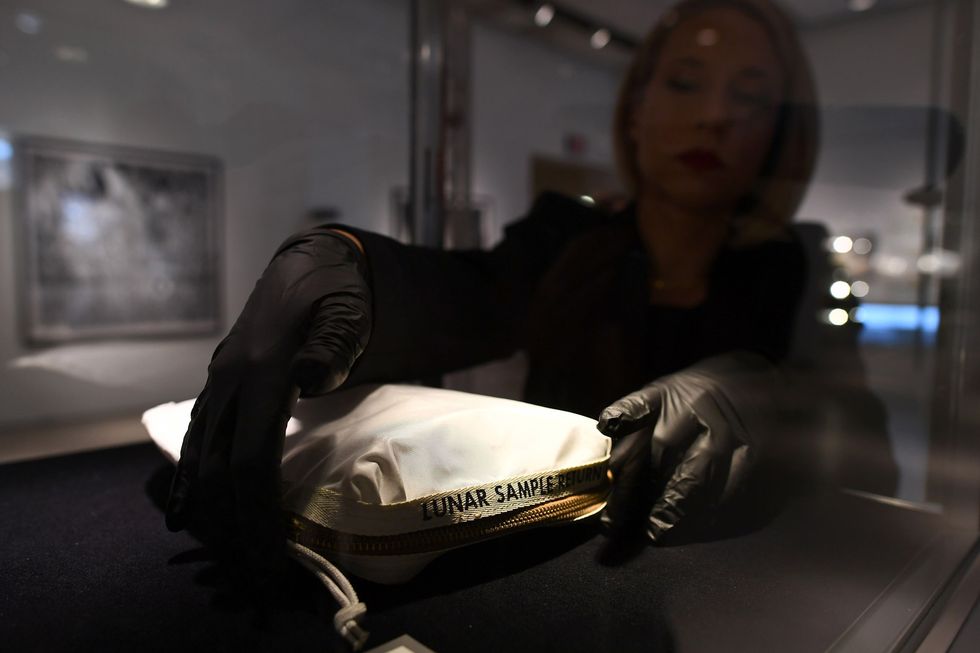

To ensure the success of the mission, NASA worked up a quicksand contingency plan. When Armstrong exited the lunar module, his first task would be to scoop up whatever material was at hand and store it in a cloth bag, labeled Lunar Sample Return, attached to his spacesuit. While the space agency hoped Armstrong would later be able to make a more thorough investigation of the lunar surface, this blind grab for material would ensure that even if the astronauts needed to make an immediate escape, they’d return to Earth with something worth analyzing.

Fortunately for Armstrong, the Sea of Tranquility lived up to its name. He took his historic steps without incident. Armstrong and fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin scoured the moon’s surface, collecting better lunar samples and sharing their observations with Mission Control in Houston. They found plenty of powder—the consequence of solar winds and a constant barrage of micrometeorites that beat down on the milky-white regolith. The dust followed the astronauts back into the lunar module. It smelled and tasted like gunpowder. But it was clear the moon had a solid crust, more than capable of supporting a spacecraft and its crew.

The footprints Armstrong left behind changed the way humans view their place in the universe. But from the beginning, NASA and other space explorers struggled to secure the physical artifacts of space travel, from the nuts and bolts of space vehicles to moon rocks themselves. While Armstrong’s lunar sample return bag should have been intended for the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, it ended up in court. At stake was a fundamental question: Can you put a price on moondust?

The lengthy legal battle to resolve this question would involve a former NASA investigator who sided against the space agency in court, a museum curator convicted on federal charges, the U.S. Marshals Service, and a very lucky auction winner. Each had their own view on the value of space-age artifacts. But only one would win—to the tune of $2.3 million.

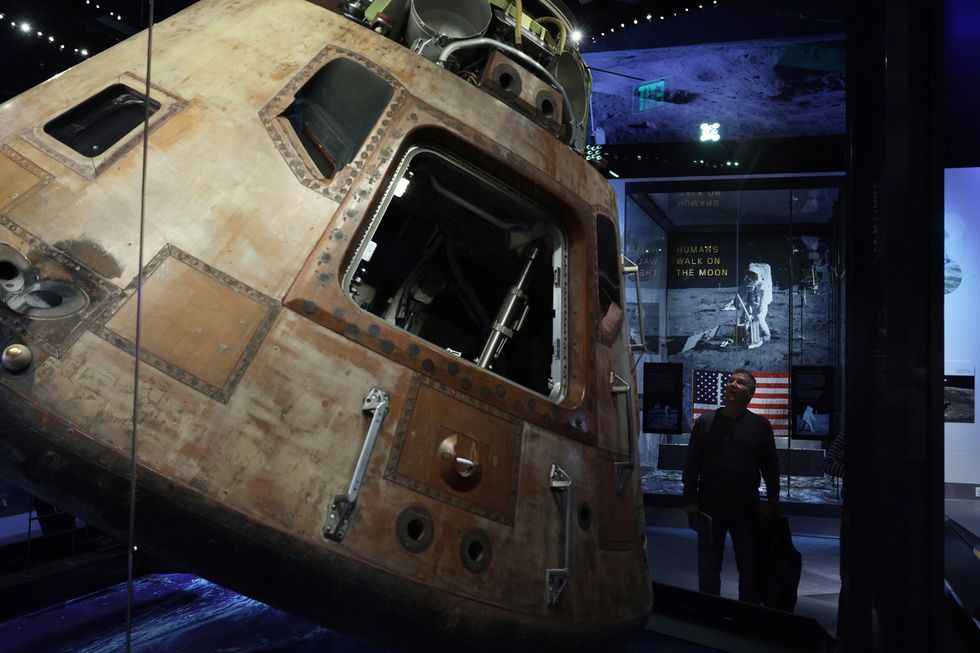

On July 24, the Apollo 11 team reentered Earth’s atmosphere. They’d left the lunar module on the moon. They jettisoned the service module—a long cylindrical spacecraft that had propelled the crew to the moon and provided them with electricity throughout their journey—midflight, just as planned. Finally, after days of discovery, the men splashed down into the Pacific Ocean in the command module Columbia, a cramped conical machine that encased the astronauts and their technical equipment.

With the first mission to the moon now complete, NASA set about recovering its assets. The Apollo program, which ran from 1961 to 1972, was to date one of the most expensive science experiments humankind had ever undertaken. But no one was really concerned about the monetary value of the individual items involved in the moon landing, says Louis Parker, a former NASA archivist. Lunar samples were carefully guarded, and some astronauts had sentimental attachment to “flown” objects, such as family photos or flags. But high-profile space auctions and internet trading sites like eBay were decades away. Apollo was historic, but it was not yet history.

The Columbia hit the water upside down. Three flotation bags soon inflated in the nose of the craft, righting it. Elite divers from the Navy’s Underwater Demolition Team encircled the capsule with a flotation collar and removed the astronauts from the metal container. A helicopter plucked the men one by one from the water before placing them in a 21-day quarantine to ensure that they didn’t bring back any contaminants from the moon. Then began the arduous task of removing the spacecraft itself from the waves. As Mission Control in Houston puffed on celebratory cigars, the divers towed the 12,250-pound Columbia to the USS Hornet, an 872-foot-long aircraft carrier floating nearby. The command module glittered like gold under the overcast skies. A crane aboard the Hornet pulled the 12-foot-diameter craft onto the runway. There, John Hirasaki was waiting to retrieve the priceless materials inside.

Hirasaki, a mechanical engineer born into a Japanese American rice farming family, opened the hatch. He quickly retrieved Armstrong’s and Aldrin’s undeveloped film, spacesuits, and lunar samples—including the lunar sample return bag—and placed everything into metal containers for shipping. A cargo plane was on standby for the nonstop flight to Houston. The next afternoon, the shipment arrived at Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, and within 48 hours, NASA proudly reported that the lunar samples were being studied at the facility’s Lunar Receiving Lab.

More than a half century of research has now chipped away at the mysteries of the moon. But in the first days and weeks after Apollo 11, the lab observed that the moondust’s most notable quality was its stickiness. Solar winds not only make the dust extremely fine, like flour, but also render it electrostatic. From the moment the astronauts landed, the grains adhered to every spacesuit, every rover, every sample collection bag—and returned with them to Earth, like a semi-toxic glitter. It was almost impossible to dislodge. It would clog equipment, including the vacuum cleaner designed to remove it. Brushes did nothing to detach it. Neither did hands, which got sandpapered by the silicate in the process. Lunar samples, it was quickly becoming clear, were both priceless and a total nuisance.

NASA was formally committed to keeping its moon rocks and moondust secure in perpetuity. Back in 1967, the United Nations brokered the international Outer Space Treaty, which stated that the exploration of the moon, and any artifacts that flowed from it, “shall be the province of all mankind.” Furthermore, NASA decided that all Apollo lunar samples were national treasure and therefore the exclusive property of the U.S. government. Private ownership, in this view, is impossible. Yet the space agency struggled to secure its haul.

From the day Hirasaki’s shipment touched down in Houston, NASA studied the lunar material in-house. But the agency also loaned rocks out to research institutions and museums around the world, exposing them to theft, damage, and loss, says Joseph Gutheinz, a former NASA investigator. Politics only complicated things further. In 1970, President Nixon gifted every U.S. state and territory, and 135 countries, moon rocks from the Apollo 11 mission. It was an act of goodwill, Gutheinz says, and a logistical nightmare. Gutheinz estimates that roughly 150 moon rocks are currently unaccounted for, many of them bestowed by Nixon. Rocks gifted to New Jersey, Puerto Rico, and Spain are just a few of the samples on Gutheinz’s most wanted list.

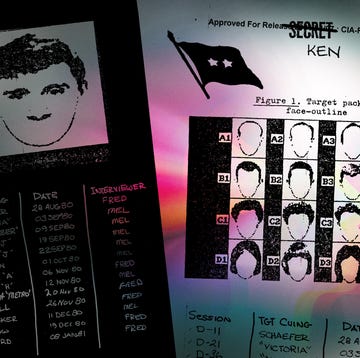

At times, NASA went to great lengths to recover its rocks. In 1998, Gutheinz led a sting operation to recover Honduras’s sample, which had landed in the hands of a former military colonel amid a coup d’état. (“My undercover name was Tony Coriasso,” Gutheinz says.) Gutheinz and his collaborators have also tracked missing goodwill moon rocks to U.S. governors’ and senators’ homes, university basements, and museum storage units. But they know that some rocks may never be found.

The government had even more trouble accounting for the other byproducts of the space race. Panels, screws, bags, gloves—no one knew exactly what was flowing into and out of Johnson Space Center. “It had grown into a pretty large monster,” Parker says. A 1967 agreement between NASA and the Smithsonian granted the National Air and Space Museum the right of first refusal over any of the objects decommissioned by the space agency. But reality got in the way.

For one, NASA took its time decommissioning its machinery. Once the Navy divers hauled the Columbia out of the Pacific, it was returned to its manufacturer, North American Rockwell, of Downey, California, where engineers studied the single-use module to see how it had performed. Rather than reuse or recycle the materials, as shuttle engineers do today, they took insights gleaned from postflight testing to guide the design and fabrication of entirely new machines for the next trip to space. Only after this testing was complete could the Smithsonian move the command module to Washington, D.C.—which they did in 1971, two years after it had dropped from the heavens.

NASA’s agreement with the Smithsonian was also undercut by handshake deals. Some engineers worked with NASA to get Apollo-era mementos formally released, with all the necessary paperwork to prove their lawful ownership. “They were pretty conscientious about that,” Parker says. “There were others that said, ‘This isn’t going to be tracked again,’” and took their favorite odds and ends home without clearance. The consequences could be serious: In 2011, when Apollo 14 astronaut Edgar Mitchell tried to sell at auction a camera he’d brought back from the moon, NASA sued its 80-year-old former employee. Mitchell claimed that management had told him he could keep the camera, but NASA said it had no formal record granting Mitchell ownership. (Mitchell eventually settled the lawsuit by agreeing to donate the camera to the National Air and Space Museum.)

The biggest impediment to archiving the Apollo missions was that NASA and the Smithsonian simply didn’t have the resources to match their ambition. The Apollo program involved 25,000 companies and 400,000 employees. It generated hundreds of thousands of artifacts, some as big as a rocket but many that were even smaller than a lunar sample return bag. “The Smithsonian, they were licking their chops,” Parker says. But the curators were 1,400 miles away, in Washington, D.C. And down in Houston, things had a way of getting lost.

Johnson Space Center sits at the intersection of two lakes: Clear and Mud. From the sky, the sprawling 1,620-acre complex looks like a home plate, with more than 100 buildings clustered inside. It’s home to NASA’s Mission Control Center, specialized laboratories for everything from lunar sample analysis to space food development, and training centers that simulate the hardships of space. But in the story of Armstrong’s backup moondust, it’s perhaps Buildings 421 and 422 that matter most.

The sprawling warehouses, bigger than a football field, still sit at the northern edge of the complex, along Space Center Boulevard. In the 1970s, the buildings, along with an adjoining storage yard, were dedicated to the “excess property” generated by the Apollo program. As the program was ending, manufacturers from around the country were returning every single nut and bolt to headquarters. There, NASA employees and volunteers sorted through semitruck shipments, airdrops, and even the wastebaskets of other Johnson Space Center employees.

Among the eager recruits was a 25-year-old named Max Ary. While NASA didn’t always see the value in its “excess property,” Ary did.

As the enthusiastic new director of a Fort Worth planetarium, Ary began writing to NASA after each lunar mission, asking for photos and technical manuals. “I was a child of the Space Age,” Ary says. “I’ll never forget, I was seven years old, waking up one morning in 1957 to my Roy Rogers alarm clock and hearing about this thing called Sputnik.” For years, Ary read every word about spaceflight, studied every diagram. Eventually he started reaching out to the manufacturers themselves on behalf of the planetarium. Whirlpool was one company to send him spare parts from their Apollo program—in that case, a water gun designed to rehydrate food in space. “When I’d go to return them, they’d say, ‘No, keep ’em, we don’t need them,’” Ary says. And so his planetarium’s collection began to grow.

Soon Ary had amassed a body of knowledge that impressed even the Smithsonian. In 1975, he was invited to join an ad hoc group of Apollo enthusiasts who would take turns looking for treasure on behalf of the National Air and Space Museum. Ary and his fellow volunteers logged the parts piling up in Buildings 421 and 422, where crates were stacked to the ceilings. “I wouldn’t be surprised if, when it was all said and done, there were half a million items,” Ary says. Using old-fashioned film cameras, they photographed every object of historical significance for curators in Washington, D.C., to review. If the Smithsonian liked an object, Ary and his colleagues stored it or shipped it for them. “I made many trips down to Houston,” Ary says. “Each trip got longer and longer.”

Some days it was dull administrative work. Each object had a part number and serial number. No one wanted to spend the money on a mainframe computer for excess inventory, Ary recalls, so Chuck Biggs, the director of public services at NASA, developed his own handwritten inventory system. Sorters wrote down each digit of each code on a legal pad, before transferring it to a typewritten form in triplicate. “It was almost an optical illusion,” Ary says. Logging items on little sleep, Ary and his colleagues knew they were making mistakes in the process. But in those days, there was no other option. “You write it down and hope for the best,” Ary says.

Other days were action-packed. “Back then, the excess-property system had a lot more holes in it,” Parker says. If Parker, Ary, or another scavenger didn’t claim a box for the Smithsonian, Parker says the delivery guys “just took it out to dumpsters and got rid of it.” NASA had an objective: Make way for the new space shuttle program. Ary remembers a shipment arriving with a nondescript label like “chairs.” But when he took a look inside the truck, he recalls, “well, here were the ejection seats” from a recent space shuttle simulator. Ary begged the driver to wait for the paperwork they needed to save the seats. The driver was impatient to move on. “I literally jumped up on the front of the truck—on the hood of the truck—and said, ‘Stop!’”

Ary saved the simulator seats from being junked. But countless other objects were melted down for metal or incinerated. “Thousands and thousands of these artifacts were just destroyed out of desperation,” Ary says. “I don’t even want to think about what we missed.”

Lunar samples were the one thing the excess-property team should never have encountered. The rocks and the dust had been designated national treasures before they’d even been collected. Any item that may have come into contact with moon rocks or moondust was sent to the Lunar Receiving Lab for processing. “Supposedly they kept track of all 842 pounds that came back,” Ary says, “and they would keep track of it to a fraction of a gram.” But things occasionally slipped through the cracks. In 2011, for example, the government recovered a single piece of tape that NASA photographer Terry Slezak had used to remove lunar dust from his fingers decades earlier. If Ary or his colleagues ever stumbled upon what looked like extraterrestrial soil, they knew what to do: Send it back to the Lunar Receiving Lab immediately.

Parker, who retired from NASA in 2011, says he’s forgetting some of the details of those days. But, he says, “Max was the ultimate scavenger.” Ary helped save many priceless artifacts for the Smithsonian. Today the Air and Space Museum has more than 3,500 artifacts from the Apollo moon landing alone, including the Apollo 11 command module Columbia; Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit, visor, and gloves; and the mobile quarantine facility the astronauts lived in aboard the USS Hornet. “You could spend your whole career going through the artifacts,” Parker says.

That still left thousands of objects without a home. NASA’s contractors never made one of any given item. They often made dozens. There were prototypes and test versions, and, of course, the final products flown to the moon. Unopened packs of astronaut food and duplicates of bags made of beta cloth (a fireproof material developed by NASA for space travel) still had value, Ary says, but they weren’t heading to the nation’s capital. So Ary improvised a mutually beneficial solution: He would ship these lesser artifacts to his own museum. “We can throw them away just as easily as you can,” he told NASA and the Smithsonian.

By 1976, Ary had uprooted his collection from the Fort Worth planetarium and moved to Hutchinson, Kansas. There he was busy transforming a local museum into the Cosmosphere, today a world-class air and space museum. Over time, Ary’s museum board acquired thousands of square feet of storage to house excess Space Age artifacts out on the prairie. “I’d estimate we probably saved well over 100,000 artifacts that would have never survived,” Ary says.

From then on, objects of national significance were always passing through Hutchinson. Ary had gained a reputation for his reassembly and restoration skills. When NASA shipped a command module simulator by boat, the machine took on seawater, causing rust. Ary agreed to refurbish it for free, provided he could display it at the Cosmosphere. “I can remember walking into his shop facility,” Parker says, “and he had this thing literally laid out all over the floor. I was impressed he’d taken it all apart like that.” The real shock came a few months later: “It was all put back together,” Parker says. “It looked like it just rolled off the assembly line.”

But it seemed like the Cosmosphere’s storage unit had been forgotten by everyone but Ary. “Some of the stuff I had, I had for 30 years,” Ary says. “NASA never asked about it. The Smithsonian never asked about it.” Over time, the lack of interest from the government led him to a regrettable conclusion: “You just make the assumption, well, it’s kind of mine, I guess,” Ary says.

The sky collapsed on Ary one night in 2003. He got a call from a friend, the astronaut Gene Cernan, who was the eleventh man to walk on the moon. Cernan had some alarming news: The FBI had just interviewed him. The topic of conversation? Max Ary.

At the turn of the millennium, the sale of space memorabilia was heating up. What NASA had considered junk just a few decades before was now selling for thousands of dollars at auction houses and on newly launched sites like eBay. A 1999 space sale at Christie’s “reset the industry,” says Robert Pearlman, founder and editor of CollectSPACE, an online clearinghouse for all things aerospace history. Lots included an equipment locker pried from the Apollo 13 command module, Gemini-era gloves, and a piece of a beta-cloth bag used on the moon. What started off as a normal auction, Pearlman recalls, quickly turned into “somewhat of a stunner.” One of Armstrong’s spacesuits, valued at $60,000 to $80,000, went for $178,500. “Suddenly we realize, everything has changed,” Pearlman says.

NASA itself was also undergoing a major change. The Apollo program had brought thousands of recent college graduates together to put a man on the moon. That meant by the 1990s, thousands of NASA contractors were reaching retirement age around the same time. “Back then, you had people who came in, did their jobs, they didn’t worry about all the aftereffects,” Parker says of the Apollo program. But when a new generation of NASA scientists, bureaucrats, and lawyers took charge, they had a new attitude: Get a handle on the moon rocks, astronaut memorabilia, and other space-age artifacts. And fast.

Gutheinz, the NASA investigator, had spent much of the 1990s hunting down fraudsters selling fake moondust. When he realized just how many real moon rocks were missing, he started setting up sting operations to recover the material. While most of the more mundane sales—of manuals and space shuttle models—were aboveboard, prosecutors were watchful for ill-gotten space goods.

The year before Cernan’s call, in 2002, Ary had left Hutchinson behind. “I had a bucket list,” he says. “I achieved all the items on that bucket list.” The Cosmosphere’s for-profit subsidiary, Space Works, consulted on the 1995 blockbuster film Apollo 13. The museum helped the Discovery Channel pull the Liberty Bell 7, a sunken Project Mercury–era spacecraft, from the depths of the Atlantic Ocean and restore it for public display. Ary’s closest collaborator, Patty Carey, was in her ninth decade. It was time, Ary felt, to move on. Now the Cosmosphere and the U.S. government were claiming that Ary had stolen their property.

What exactly happened depends on who you ask, says Pearlman, who documented each development in Ary’s case for CollectSPACE readers. When Ary left the Cosmosphere, the curator who replaced him conducted an audit of the museum’s roughly 12,000 pieces. The curator noticed that some items were missing—about 400 in total, when first reported. Some had been loaned for the Apollo 13 film and never returned, subsequent investigations revealed. Others turned up with time. But still others had been auctioned online.

In 1999, court documents show, Ary had created two accounts with Superior Galleries, an auction house based in Los Angeles. One was a personal account, and one was an account for the museum. This was not in itself illegal; Ary was a private collector, and museums buy, sell, and trade items from their collections all the time. But over the next two years, Ary went on to sell a number of items through his personal account that didn’t technically belong to him, according to the U.S. Attorney in Wichita, pursuing the case on behalf of NASA.

Between the items Ary sold online and the artifacts recovered by the FBI during a raid on his home, about 120 of the Cosmosphere’s missing objects were connected to Ary. Of the ones Ary auctioned, two had been loaned to the Cosmosphere by NASA: a flown list of codes used by the command module computer and an Apollo 15 tape.

In April 2005, Ary was indicted in federal court on counts of wire fraud, mail fraud, theft of government property, and interstate transportation of stolen property. In court, former coworkers, including Louis Parker from NASA, were called to testify. That November, a jury convicted Ary on 12 counts and he would later serve two years in prison.

Other collectors of space memorabilia got caught in the fray. Pearlman was among those who’d unknowingly purchased an item at auction that courts later determined Ary did not have the right to sell. The CollectSPACE founder had won a detached spacesuit pocket at auction that had been labeled as a backup produced for Apollo 16. “In the course of the court case, it was revealed it actually flew on Apollo 16, so I got an incredible deal on it,” Pearlman jokes. But after the federal government contacted Pearlman, he returned the object to the Cosmosphere.

Ary, now 74, maintains his innocence. He says the intermingling of his personal collection with the Cosmosphere’s from the museum’s inception, combined with clerical errors stretching back to the 1970s, were to blame for the confusion. But in the minds of NASA’s new guard, Ary says, his explanations were worthless. No one believed that “these artifacts could have been thrown away,” Ary says. It didn’t matter, he adds, that “they didn’t know the difference between a Mercury capsule or a Tylenol capsule.” That part of Apollo history—of what transpired in Buildings 421 and 422—had already been lost.

Today Ary is back to work, this time as the director of the Stafford Air & Space Museum in Weatherford, Oklahoma. While he has a startlingly quick memory of events long past, he still struggles to talk about the emotional impact of his legal odyssey and two years behind bars. “At the time, it didn’t go by very fast,” Ary says. “I decided, ‘I have to get this out of my mind. I can’t do anything about it.’” Now he tries to see it as one chapter of an otherwise momentous 55-year career. But one man’s worst nightmare would soon prove to be another woman’s lucky break.

In March 2015, Nancy Lee Carlson, a lawyer with a passion for space exploration, scrolled through a Texas-based auction company catalog. A white beta-cloth bag piqued her interest. The details were sparse: “One flown zippered lunar sample return bag with lunar dust (“Lunar Bag”), 11.5 inches; tear at center,” the listing read. “Flown Mission Unknown.” But, Carlson told the Wall Street Journal, she felt that the bag “had a story I could figure out.” She nabbed it for $995—more than she’d ever spent at auction before. (Carlson could not be reached for further comment.)

When the bag arrived at Carlson’s home in Inverness, Illinois, the inside was coated with a sticky dust. She decided to ship the bag to NASA for further testing. Before she sent it off, Carlson had also found a part number, clearly labeled inside. After a few months of digging, and radio silence from NASA, Carlson found a corresponding code in the Apollo 11 inventory: “V36-788-034 Decontamination bag, contingency lunar SRC.” The story was coming together—and it was a good one.

In May 2016, after months of waiting, Carlson got the confirmation: Her bag indeed contained lunar dust from moon rock samples collected during Apollo 11. And they weren’t just any sample. The specific geology of the rocks, along with the part number, suggested that her bag was the one Armstrong used to collect the first-ever samples of the moon. The hidden gem had been among Max Ary’s assets seized by the U.S. Marshals Service. It was mistakenly auctioned off to pay for Ary’s court-ordered restitution to previous buyers like Pearlman.

The news came from a surprising source. Instead of NASA’s moon rock laboratory, Carlson heard from the District Attorney in Kansas. NASA had asked the court to revoke the results of the auction. The agency claimed that it was the rightful owner of the bag, along with the moondust inside. The government was willing to give Carlson $995 for her trouble. So Carlson decided to sue the U.S. government.

Ary says he never knew the value of the bag. NASA claims to have lent the bag to the Cosmosphere in 1981, but the agency was not able to find a loan agreement. Ary thinks it’s more likely he picked it up in the 1970s when he was routinely sorting objects at Johnson Space Center.

In those days, cloth bags were so commonplace that NASA shipped some of its artifacts with the bags as packing material, Ary recalls. “You had enough bags to cover the earth,” he says. “You didn’t even look at them after a while.” In hindsight, Ary believes this particular bag looked so worn that he probably planned to cut it up into scraps for students to touch, as he often did with spare beta cloth. “Probably the most interesting thing about that bag was how uninteresting it was,” he says.

Fortunately, Ary never got around to slicing and dicing. Instead, the bag entered into the Cosmosphere’s records in the early 1980s with a description similar to the one offered by the auction house: “Lunar Sample Return Bag, Flown Mission Unknown.” Its value was estimated at $15. When Ary left for a new job, the bag somehow ended up with him.

Now that NASA knew the true value of the worn-out beta cloth, the agency was desperate to keep it. “This artifact was never meant to be owned by an individual,” NASA spokesperson William Jeffs said in a 2017 statement. It had both scientific and historical significance and had been sold to Carlson by accident. NASA wasn’t wrong: Proper procedure dictated that the U.S. Marshals work with NASA to identify anything the government wanted among Ary’s personal possessions before auctioning them off. And there was precedent for seizing other lunar samples that entered the market, like Gutheinz and his Honduran goodwill moon rock sting operation.

To everyone’s surprise, Gutheinz, now retired from NASA, ended up supporting Carlson’s case. “I’m guilty as probably anyone else at NASA, because my gut-level first reaction to this was, ‘This isn’t her property. This is a national treasure,’” Gutheinz says. But he looked deeper and determined the fault was with the U.S. Marshals, for not clearing the sale with NASA. Once they’d made their error, the sale to a private citizen was perfectly legal. “I do not believe in private ownership,” Gutheinz says, “except for Nancy Lee Carlson.”

A U.S. district court agreed. In 2016, after a yearlong court battle, a federal judge ruled that NASA must return the bag to Carlson. In 2019, Carlson sold it at auction for $1.8 million. “This is my Mona Lisa moment,” Cassandra Hatton, an expert with Sotheby’s auction house, has said. But NASA never returned the moondust test samples from inside the bag, so Carlson sued NASA once more. She won again and quickly set about selling this artifact, too.

To find a buyer, Carlson now turned to Bonhams. The international auction house has dealt in art, antiquities, and rare books, as well as artifacts from the history of science and technology, since the 18th century. Adam Stackhouse, a specialist at Bonhams, knew that Carlson had something special on her hands. “You hold it and it just really transports you to that moment,” he says. It was like holding the moon landing in your hands. But the story was mostly in the holder’s head.

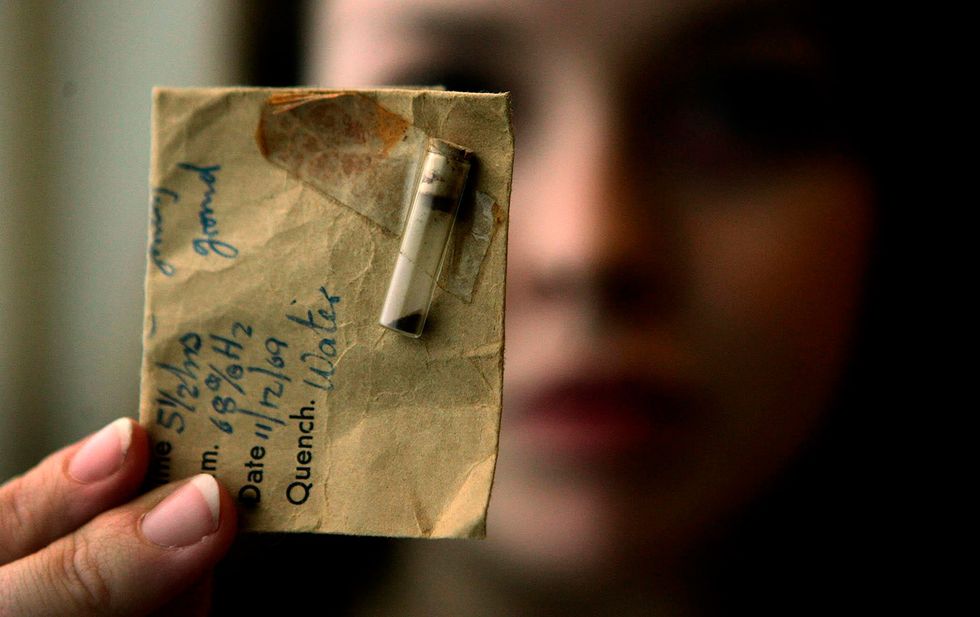

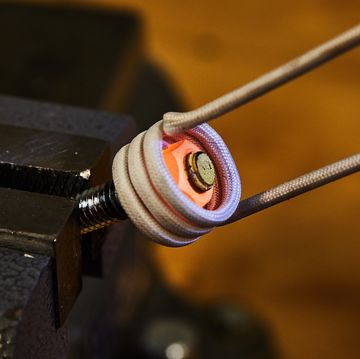

To collect the dust for testing, NASA scientists had scoured the interior of the lunar sample bag with carbon tape, going so far as to rip the bag open at the seams for better access to the invisible grains. Then they affixed the black strips to aluminum discs and analyzed them under a scanning electron microscope. When the electrons hit the atoms in the moondust, it created a black-and-white image of the lunar sample’s topography. Cool—but invisible to the naked eye.

What really enticed prospective buyers to line up or log on to the hybrid auction in April 2022 was that Carlson’s sample had a one-of-a-kind provenance. In previous cases where moon samples had fallen into private hands, NASA had successfully reclaimed the rocks or dust. Carlson’s sample was different. “It was NASA verified,” Stackhouse says. “It was legal to sell.” It was, for now, most buyers’ only hope of owning a piece of the moon. In the end, the specks sold for just over $500,000.

Space-age sales skyrocketed in the 1990s, and they’ve never fallen back to Earth. As with art or antiques, collectors see the value in NASA-originated artifacts. But the way they show their care can vary widely: Some collectors protect objects overlooked by museums, while others find ways to share their belongings with the world. Still others keep things for themselves.

To date, the collector (or collectors) who purchased Armstrong’s bag and the moondust inside has chosen to remain anonymous. They have not elected to loan their objects out to a museum, either. Space enthusiasts like Pearlman can only speculate about the fate of the artifacts. Perhaps the objects are displayed in a wealthy person’s home, he says. Or secured in a vault like any other asset, and not enjoyed by anyone. They are all perfectly valid choices, Pearlman says, but the anonymity eats at him. “I would just like to have some public accountability so it’s not lost to history—again,” he says.

As new countries set their sights on the moon, including Japan, South Korea, Russia, India, and the United Arab Emirates, questions of ownership become even more complicated. How will other space agencies choose to handle their moon rocks? What will the United States, which plans to land a woman and a person of color on the moon in the Artemis program, do differently this time? And what lengths will people continue to go to in order to get their hands on a piece of the moon?

Eleanor Cummins is a freelance science journalist in Brooklyn whose work can be found in The Atlantic, The New York Times, National Geographic, The Verge, WIRED, and more. She is also an adjunct professor at New York University’s Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program.