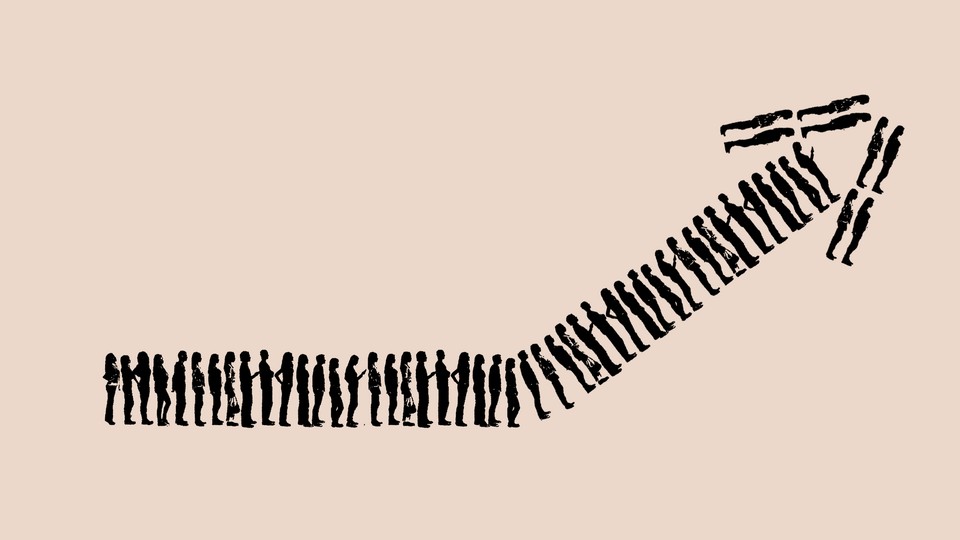

Inflation is an everyone problem and unemployment is a some-people problem.

Keep that fact in mind as good-to-great headline economic numbers keep rolling in and economic sentiment remains abysmal. This week, the Commerce Department reported that real GDP fell 0.4 percent in the first quarter of the year, largely because of fluctuations in inventory orders and international trade. Consumer spending and business investment both looked strong, indicating an economy growing a tad faster than it did last quarter, not one teetering on the edge. Employment data look even better: Companies added 431,000 employees to their payrolls in March, with the jobless rate falling to just 3.6 percent.

But American consumers still say that the economy is on the “wrong track” and that financial conditions are getting worse. The Commerce Department also reported that prices increased 6.6 percent year-over-year in March, the sharpest rise in 40 years, with food costs up more than 9 percent and energy costs up a whopping 34 percent. Wages, though growing at their fastest pace in decades, are not keeping up with the price increases for many Americans.

Still, is the economy now really as bad as it was in, say, 2008, when the financial system was on life support and millions of homeowners were underwater on their mortgage? Is it worse than it was in 2011, amid a profoundly unequal recovery and crisis levels of long-term unemployment? Are the problems of having too much money sloshing around more dire than the problems of having too little of it?

The answer to all of those questions might be no. Still, it is not much of a mystery as to why the economy feels so bad to so many. The direction of the economy feels uncertain. The Federal Reserve is attempting to tamp down on inflation without triggering a recession, as it has done successfully, ahem, once in the recent past, while failing several other times. Meanwhile, governors across the country are trying to stop inflation with policies that are known to gin it up, a bit like trying to douse a fire with nail-polish remover.

Beyond that, the economy feels so bad for so many because it feels so bad for so many. Downturns tend to cause concentrated economic pain for a few, leaving many others unscathed; this was true in the Great Recession and the COVID recession, as massive as they both were and as high as the unemployment rate climbed during each. Most Americans did not lose their jobs, and wealthy Americans, in particular, were unlikely to be unemployed. Everyone experienced the fear of living through an economic crisis, with many people suffering from reduced employment opportunities, lower wage growth, and so on. But the pain was uneven.

In contrast, nobody escapes inflation, even if rising prices affect some people far more than others. That includes people on fixed incomes, such as retirees. It also includes lower-income families, who have less room in their budgets to absorb higher prices, as well as fewer opportunities to cut costs by switching from nice goods to bargain-basement ones, than higher-income families do. Indeed, the lower part of the income spectrum has been experiencing higher rates of inflation than the upper part, as well as struggling with it more, dollar-for-dollar.

Today’s inflation comes on top of a long-simmering affordability crisis, too. The price of housing is sapping budgets and forcing families to make awful decisions to keep down costs: living far away from family, commuting long distances, giving up on having a third kid, renting forever instead of ever trying to buy. The costs of child care, elder care, higher education, and medical care remain outrageous as well—affecting families far up the income scale, though of course those at the bottom are the most burdened.

One good thing about this mixed, unusual economy is that it is helping the worst-off in one important way. Very low unemployment rates and outright worker shortages are leading employers to offer jobs to people who often struggle in the labor force—individuals with a felony on their record, for instance.

But it is also pushing up gas prices and grocery bills, when rent was too expensive to begin with and child care was priced like a luxury good already, and as Washington is worrying about triggering a new downturn. No wonder everyone is mad.