Approach Considerations

Trusses place pressure on the skin and bowel, induce related injury, and mask signs of incarceration and strangulation. The temporary use of binders or corsets can be useful in patients with large-necked hernias, during the preoperative period, or in situations where there is a high risk of operation on a long-term basis.

Hernia reduction or repair may be carried out, depending on the type of hernia and on whether incarceration is present (see below). Reduction can often be carried out in the emergency department (ED), but a surgeon should be consulted for the following reasons [30, 6] :

-

Inability to reduce the hernia

-

Concern for a strangulated bowel and a patient with a toxic appearance; all incarcerated or strangulated hernias demand admission and immediate surgical evaluation

-

Comorbid risks for sedation; patients with such risks should have a surgeon present for the initial reduction attempt

Surgical options depend on the type and location of the hernia.

Inguinal hernia

In general, the presence of an inguinal hernia, in the absence of mitigating factors, constitutes an indication for repair to prevent the complications of prolonged exposure (eg, incarceration, obstruction, and strangulation). [31] Although pressure reduction of an incarcerated hernia is generally safe, failure to reduce is not infrequent and mandates prompt exploration.

Signs of inflammation or obstruction should rule out attempts at reduction. Difficult reduction should promptly be followed by repair. Unintentional reduction of the intestine with vascular compromise leads to perforation and peritonitis with high morbidity and mortality. En masse reduction after vigorous attempts at reducing a hernia with a small fibrous neck results in ongoing compromise of the entrapped bowel.

Umbilical hernia

In adults, umbilical hernia repair is indicated for incarceration, a small neck in relation to the size of the hernia, ascites, chromatic skin change, or rupture. In children, the approach to managing an umbilical hernia is related to the natural history of umbilical hernias and their importance in adulthood.

Most umbilical hernias close spontaneously in children during the preschool-age period. Therefore, repair of an umbilical hernia is not indicated in children younger than 5 years unless the child has a large proboscoid hernia with thin, hyperpigmented skin or is undergoing an operation for other reasons or if the hernia causes familial or social problems.

It is the size of the fascial defect, rather than the size of the external protrusion, that predicts the potential for spontaneous closure. Walker demonstrated that fascial rings measuring less than 1 cm in diameter usually close spontaneously, whereas rings larger than 2 cm seldom do. [22] Accordingly, many pediatric surgeons will repair umbilical hernias with large (>2.5 cm) fascial defects earlier than hernias with smaller fascial defects.

Incarceration of umbilical hernias is rare in the pediatric population. Over a 15-year period, only seven children with an incarcerated umbilical hernia were reported at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. In comparison, 101 cases of umbilical hernia incarceration occurred in adults at that institution during the same 15-year period. Omentum is the most frequently incarcerated organ.

Other hernia types

Painful preperitoneal fat in an epiplocele or paraumbilical hernia may be incarcerated. Because these defects will not close spontaneously and a propensity exists for painful strangulation, elective outpatient repair is recommended.

Because of the potential for incarceration, spigelian hernias should be repaired, as should interparietal, supravesical, lumbar, obturator, sciatic, and perineal hernias. Notably, strangulation can occur in a Richter hernia without evidence of incarceration or obstruction.

Elective vs acute repair

A retrospective, single-institution study reported that patients with femoral, scrotal, and recurrent hernias, as well as patients of advanced age, are more likely to undergo acute hernia repair versus elective hernia repair. [32] Acute hernia repair reportedly has a higher morbidity and lower survival rates than elective hernia repair does.

Contagious disease, diaper rash, nearby open wounds, an upper respiratory tract illness, or other intercurrent illness should delay an elective procedure; other delays probably increase the risks of operative complications. In cases where the risk of operation exceeds that of potential problems from the hernia, nonoperative observation is wise.

Hernia Reduction

In attempting hernia reduction, the first step is to provide adequate sedation and analgesia so as to prevent straining or pain. [1, 5, 33] The patient should be relaxed enough that he or she will not increase intra-abdominal pressure or tighten the involved musculature.

The patient should be supine, with a pillow under the knees. For an inguinal hernia, the patient should be placed in a Trendelenburg position of approximately 15-20°. The ipsilateral leg is placed in an externally rotated and flexed position resembling a unilateral frog leg position. A padded cold pack may be applied to the area to reduce swelling and blood flow while appropriate analgesia is established. Ice cooling of an incarcerated hernia is counterproductive.

Simple pressure over the distal sac usually is ineffective, in that the incarcerated viscera are likely to mushroom over the external ring (see the first image below). Instead, two fingers are placed at the edge of the hernial ring, and firm, steady pressure is applied to the side of the hernia contents close to the hernia opening and maintained for several minutes while the hernia is being guided back through the defect (see the second image below).

In children, pressure should be applied from the posterior and directed laterally and superiorly through the external ring. It should be kept in mind that the internal ring in infants is more medial than the internal ring in older children and adults. The hourglass configuration of a hernia -hydrocele complex will not reduce with pressure applied to the hydrocele portion.

If success is not achieved after one or two attempts at reduction, a surgeon should be consulted; repeated forceful attempts are contraindicated. Pain after a successful reduction may indicate a strangulated hernia, necessitating further evaluation by a surgeon.

The spontaneous reduction technique requires adequate sedation and analgesia, Trendelenburg positioning, and padded cold packs applied to the hernia for 20-30 minutes. This can be attempted before manual reduction attempts.

Topical Therapy

Cauterization with silver nitrate aids in the resolution of an umbilical granuloma. If there is a stalk, ligation of the base resolves the problem. Delaying the repair of umbilical or asymptomatic epigastric hernias until children are older than 5 years allows spontaneous closure in most children. Strapping, with or without a coin, is not indicated in the treatment of umbilical hernia, because of problems with skin erosion and lack of effectiveness.

Grob introduced the use of merbromin as an escharotic for scarifying the intact sac of a giant omphalocele. However, the development of mercury poisoning terminated its use. Chemical dressings using silver sulfadiazine (which has leukopenia as a complication), povidone-iodine solution (hypothyroidism as a complication), 0.5% silver nitrate solution (argyrism as a complication), and gentian violet have served as agents to protect against infection while the sac epithelializes.

In current practice, only life-threatening associated conditions, poor probability of survival in infants, or failure of better means of coverage warrant use of these methods. A large residual ventral hernia results, which may be problematic because of loss of domain.

Progressive compression dressing of an omphalocele sac with an inner layer of saline moistened dressings and an outer dressing of a self-adhesive compression bandage can reduce viscera over 5-10 days, after which time delayed primary fascial and skin closure is accomplished.

For children with an omphalocele and life-threatening associated conditions, a poor probability of survival, or a very large omphalocele, the combination of topical escharotic agents and daily abdominal wrapping with an elastic bandage has produced successful closure in many patients.

As the child grows, the defect remains the same size and becomes smaller relative to the increasing abdominal wall. Delayed closure following epithelialization can allow primary fascial closure with no prosthesis, which eliminates the need for multiple operations. External coverage with pigskin, skinlike polymer membrane, or human amniotic membrane can be used adjunctively in the treatment of giant omphalocele or after failed primary therapy.

Surgical Repair of Inguinal Hernia

The fundamentals of indirect inguinal hernia repair are basically the same, regardless of the age at presentation. Reduction or excision of the sac and closure of the defect with minimal tension are the essential steps in any hernia repair. If tissue is sufficiently attenuated as to preclude following these precepts, many techniques involving the release of tension by flaps, prosthetic materials, or a simple relaxing incision in adjacent tissue will fulfill the requirements. Overlay, underlay, and sandwiching of the edges with plastic meshes constitute most techniques today.

Return to work is dictated by the approach and the amount of physical activity involved with the job. Accurate postoperative instruction and easy access to care (if problems arise) are as effective as a full postoperative visit following routine inguinal hernia repairs.

Basic repair techniques

Bassini and Shouldice repairs

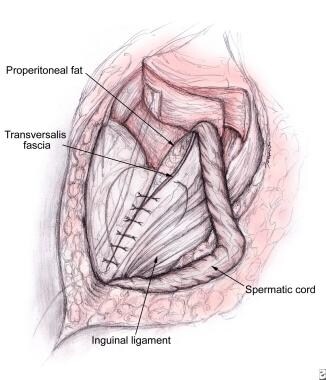

The essence of the Bassini repair is apposition of the transversus abdominis, transversalis fascia, and lateral rectus sheath to the inguinal ligament. This is usually performed by imbrication (see the image below). The Shouldice technique uses two layers of continuous suture in a similar fashion.

Bassini-type repair approximating transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascia to iliopubic tract and inguinal ligament.

Bassini-type repair approximating transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascia to iliopubic tract and inguinal ligament.

Cooper repair

The Cooper repair approximates the conjoint area, transversus abdominis, and transversalis fascia to the pectineal (Cooper) ligament. Overlying the vein, these structures are sewn to the iliopubic tract. This technique also provides a good approach for the repair of femoral hernias.

Tension-free mesh repairs

The standard adult hernia repair now uses prostheses to reinforce the floor, usually polypropylene mesh. The material can overlay, underlay, or sandwich the area or can be used as a plug. This provides a tension-free repair and excellent results, but it carries a slightly increased risk of wound infection. The Lichtenstein hernioplasty is currently one of the most commonly performed mesh-based tension-free repairs (see Open Inguinal Hernia Repair).

The preperitoneal approach has advocates who claim that this approach makes it easier to identify the sac, reduce the contents, and dissect the cord structures. Mechanical advantages include the use of natural intra-abdominal pressure to keep the mesh in place over all potential hernia sites. The best uses are in the repair of hernias incidentally encountered during other abdominal procedures, recurrent hernias, and femoral hernias.

A Pfannenstiel, lower midline, or other incision is used to reach the preperitoneal plane. The internal inguinal ring and the hernia sac are identified lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. After the sac is dissected from the testicular vessels and vas deferens, it is divided and the peritoneum closed. The repair follows the pectineal approach and often has mesh applied.

Simple repair for pediatric hernias

A simple inguinal hernia repair is possible in children because of the smaller size, better muscle tone in the canal, and rapid recuperation. Excision of the hernial sac (processus vaginalis) is usually sufficient, with little need for prosthetic repair of an attenuated internal ring or posterior wall of the inguinal canal. Either preincisional injection of the incision site or a caudal block is preferable to no preincisional therapy. [34]

A small incision is made just superior and lateral to the pubic tubercle in the suprapubic skin crease, centering the operative field near the internal ring. The external oblique aponeurosis is incised in the direction of its fibers, or the internal and external rings are transposed by laterally retracting the latter. Tugging on the testis helps visualize cord structures. The glistening white hernia sac often bulges up amid the cord. The sac, located anteromedial to the cord, is elevated from the floor and carefully dissected free from the vas deferens and testicular vessels.

Short hernia sacs are freed to the internal ring, but long sacs are often best divided. Proximal dissection to the internal ring should extend until preperitoneal fat is visible circumferentially. Twisting the sac before ligation provides strength and narrows the internal ring. The sac is ligated at its base. Because of occasional postoperative “spitting” of a nonabsorbable (eg, silk) suture, synthetic sutures are used for sac ligation.

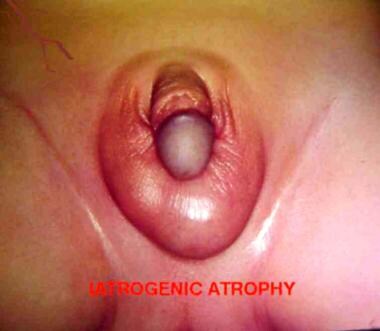

If fascial repair seems necessary, the transversalis fascia is sutured to the shelving margin of the ilioinguinal ligament. The incision is closed in layers, and a single adhesive strip is placed. The testis must be pulled into the scrotum to prevent iatrogenic cryptorchidism (see the image below).

Iatrogenic cryptorchid testis in child. Taking care to position testis in scrotum is integral part of completion of hernia repair in boys.

Iatrogenic cryptorchid testis in child. Taking care to position testis in scrotum is integral part of completion of hernia repair in boys.

Approximately 2% of girls with inguinal hernias have an intersex differentiation syndrome. Each girl should have the fallopian tubes and ovaries examined directly or via peritoneoscopy. The hernia sac of a female patient must be scrupulously examined for signs of testicular tissue if it contains an ovary.

The most common cause of this is testicular feminization (androgen insensitivity) syndrome, which results from end-androgen resistance and leads to a small testis and a rudimentary vagina (persistent genitourinary sinus) without fallopian tubes or a uterus. If a girl with a hernia has testicular feminization, a gonadectomy on one side and isolation of the other gonad in a superficial position until puberty permits secondary sexual characteristics to develop. Hermaphrodites have an asymmetric ovotestis, which should not be removed.

An incarcerated object within an inguinal hernia in a girl, especially in an infant, is usually an ovary. An incarcerated ovary is not usually reducible, but strangulation is infrequent, making surgical reduction of the irreducible ovary less urgent than reduction of an incarcerated intestine would be. A child with an incarcerated hernia containing the intestine that successfully is reduced should be admitted for 1 day to allow resolution of edema before repair.

A child with tachycardia, fever, or signs of obstruction must be operated on immediately. Fluid and electrolyte correction and antibiotic administration precede the operation. Testicular atrophy occurs with incarcerated pediatric hernias, and the parents should be warned of the possibility.

Exposing and opening the sac before dividing the external ring permits the contained intestine to be controlled with a clamp, preventing unintentional release of the bowel into the abdomen. Once the viability of the incarcerated intestine is ensured, dividing the external ring (and sometimes the internal oblique muscles) laterally will reduce it.

Laparoscopy through the hernia sac can be used to assess visceral viability if incarcerated intestinal contents reduce before visualization. The gangrenous bowel is resected, an end-to-end anastomosis is performed, and the intestine is returned to the abdomen. Repair of the contralateral side, if required, is deferred. An apparently infarcted testis is left in place after a capsulotomy is performed.

Laparoscopic repair techniques

Laparoscopic techniques are increasingly being used to repair both primary hernias and recurrent hernias (see Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair). The totally extraperitoneal (TEP) approach is usually favored over the transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach because of the complications that arise from exposed intraperitoneal mesh in the latter. Postoperative pain, time to full recovery, and return to work are improved with the laparoscopic approach, but it is more expensive. Short-term recurrence data are comparable so far.

For most abdominal wall hernias, laparoscopic repair probably represents the future. [35] As the cost of instrumentation decreases, procedure-specific instrument design improves, and the laparoscopic learning curve is obliterated, the saying “if all else is equal, less pain and better cosmesis win out” will hold true. For example, prospective studies out of Europe found laparoscopic repair of pediatric hernias to be comparable to the results of open surgery. [36] The use of new materials or techniques may alter the approach. [37]

In a retrospective cohort study of 79 patients who underwent laparoscopic repair of primary ventral hernias and 79 who underwent open hernia repair, patients with a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair were significantly less likely to develop a surgical site infection (7.6% vs 34.1%). However, patients who underwent laparoscopic repair were more likely to develop a postoperative ileus (10.1% vs 1.3%), to have a persistent bulge at the operative site (21.5% vs 1.3%), and to have a longer hospital stay. [38, 39]

Treatment approach

Adults

After a diagnosis is established, the signs, symptoms, and risks of incarceration, as well as the timing, conduct, and risk of the repair procedure, should be explained to the patient or caregiver. Most repairs proceed within several weeks, with the precise timing dependent on multiple factors (eg, employment and insurance).

With massive hernias, prosthetic material is usually needed to aid closure, and appropriate materials should be available in the operating room before incision. Progressive pneumoperitoneum, using increasing volumes of air over time, may allow accommodation to increased intra-abdominal pressure but probably does little to increase the size of the abdominal cavity.

Adults with very large chronic hernias should be admitted postoperatively because of the combination of ileus from extensive manipulation and loss of domain with the attendant problems of increased pressure on the diaphragm, vena cava, kidneys, and hernia closure. Adults who present with bilateral hernias without the need for formal reconstruction can undergo simultaneous repair; more complex procedures require the repairs to be separated by at least 1 month.

Local anesthesia is sufficient for most repairs in adults; however, prolonged procedures, repair of hernias with a large intraperitoneal component, including laparoscopy, and repair of recurrent hernias are best managed with spinal, epidural, or general anesthesia.

Routine preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis is not currently recommended for low-risk adults undergoing a standard tension-free mesh-based repair; multiple studies have shown this practice to be of no benefit in decreasing postoperative wound infection.

Patients undergoing a neurectomy have a significantly lower prevalence of neuralgia without increased paresthesia.

Children

In healthy full-term infant boys with asymptomatic reducible inguinal hernias, regardless of age or weight, pediatric surgeons typically carry out repair soon after diagnosis. [20] In full-term girls with a reducible ovary, most surgeons operate at a close elective date, but more urgent scheduling of surgery is preferred if the ovary is not reducible but asymptomatic.

Premature infants with inguinal hernias usually undergo repair before being discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), but this practice is changing, and infants are now being discharged home at much lower weights. Some surgeons prefer to postpone the surgery in these very small babies for 1-2 months to allow further growth.

All children with a bilateral presentation should undergo bilateral inguinal hernia repair under a single anesthesia. However, there remains some controversy regarding the correct approach to exploration of the contralateral side in pediatric inguinal hernias. [40] The potential damage to the spermatic cord structures in boys and the low incidence of contralateral hernia development in infants (< 1 year) and older children argue against routine contralateral groin exploration. [41, 42]

The previous practice of routinely exploring the opposite side in all boys younger than 2 years and all girls younger than 4-5 years is no longer popular. Most surgeons do not routinely perform open exploration of the contralateral groin, except in cases of high anesthetic risk, significant risk for developing contralateral hernia secondary to increased intra-abdominal pressure, or limited access of the child to appropriate medical care should an incarceration occur on the opposite side.

Current practice in many pediatric centers uses peritoneoscopy through the ipsilateral inguinal sac to identify contralateral patent processes and hernias. [43] Long-term follow-up is needed because only 20% of the patent processes identified become clinically apparent hernias in the short term.

A surgeon who is unfamiliar with the tissue characteristics and metabolic and psychological needs of children or who does not have a skilled pediatric anesthesiologist available should not attempt a hernia operation in a young child. Older children usually have general inhalation anesthesia, whereas some anesthesia providers use spinal or continuous caudal anesthesia with preterm infants. Preemptive regional anesthesia, by ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve block or by caudal block, decreases postoperative discomfort.

Routine use of perioperative antibiotics for uncomplicated inguinal hernia repairs in children is not generally indicated. Some cardiologists advise prophylactic antibiotic use to lower the risk of endocarditis in children with associated cardiac defects; patients with ventriculoperitoneal shunts may also benefit.

Postoperative apnea is common in premature infants. [44] Those younger than 50 weeks’ gestational age should be admitted for 24 hours postoperatively and placed on a cardiorespiratory monitor. [45, 46, 47]

Sliding hernia

In about 40% of girls with an inguinal hernia, the fallopian tube (or, occasionally, the ovary or uterus) is a sliding component of the hernia that cannot be easily reduced into the abdominal cavity. The sac wall may seem too thick in the medial or lateral quadrants, or the contained viscus (particularly the fallopian tube and ovary) may not be reducible into the peritoneum. The walls must then be inspected for a sliding component.

To repair a sliding hernia, the sac is ligated distal to the fallopian tube and divided. The proximal sac is ligated and then invaginated into the peritoneal cavity. A purse-string suture inside the opened hernia sac may be used to aid in visualization during sac closure. The internal ring is closed with sutures from the transversalis fascia to the iliopubic tract.

Surgical Repair of Other Hernia Types

Masses in femoral canal

Atypical tuberculous adenitis is best treated by means of local excision. Repeated trauma may cause painful reactive inguinal or femoral lymph nodes. Excision of the involved node relieves symptoms. The potential for malignancy in a femoral canal mass that persists despite antibiotic therapy warrants biopsy. Any enlarged lymph node that is excised should be divided, with one half sent fresh for lymphoma protocol and the other half sent to microbiology. A suspected femoral hernia, usually after a missed inguinal hernia repair, also warrants exploration.

The best approach for both adenopathy and femoral hernia is a preperitoneal approach. Reduction of an incarcerated intestine is easy, and there is clear access to the lymph node. A pectineal ligament repair or laparoscopic mesh placement closes the opening into the femoral canal. Groin incisions usually heal better than thigh incisions, particularly with lymph channel disruption.

Umbilical hernia

In children, umbilical hernia repair is best performed with general anesthesia, whereas in adults, regional or local anesthesia can be used. A semicircular incision in the infraumbilical skin crease exposes the umbilical sac. A plane that is created to encircle the sac at the level of the fascial ring expedites repair. The defect is closed primarily in a transverse direction with a single layer of interrupted sutures. If the defect is very large, mesh is occasionally required.

Although excessively wrinkled skin can appear cosmetically troublesome, elasticity and growth usually corrects the problem because the skin incision lies within the umbilical fold. In cases with severe redundant skin, removal of a circle of skin and peritoneum to access the hernia, followed by a purse-string closure, provides an excellent cosmetic result. A pressure dressing is applied for several days after repair.

Epigastric hernia

Immediately before the operation, the defect should be marked with the patient standing. After anesthetic induction, a small vertical incision directly overlying the defect is carried to the linea alba. Incarcerated preperitoneal fat may be either excised or returned to the properitoneum. The edges of the fascial defect are approximated transversely with interrupted sutures. Recurrence is rare, though a second epigastric hernia may develop elsewhere as a separate defect.

Spigelian hernia

Despite being rare and difficult to diagnose, spigelian hernias are easily approached. A transverse incision over the hernia to the sac allows dissection to the neck, and clean approximation of the internal oblique muscle and transversus abdominis completes the repair. Laparoscopic repair allows accurate delineation of the anatomy and helps establish the diagnosis in suspect instances.

Interparietal hernia

Because most interparietal hernias are associated with an undescended testis, the spermatic cord should be identified. In a young child, an orchiopexy is performed if the testis is not gangrenous; in an older child or adult, the testicle should be removed. For the usual presentation of bowel incarceration, a properitoneal indirect inguinal hernia repair is the best approach.

Supravesical hernia

Supravesical hernias are repaired with the standard techniques used for inguinal and femoral hernias, usually via of a paramedian or midline incision. The internal supravesical hernia repair should include division and closure of the neck of the sac.

Lumbar hernia

A lumbar hernia is best approached with the patient in the lateral decubitus position and with the use of a lumbar roll or kidney rest. A skin-line oblique incision extends from the 12th rib to the iliac crest. A layered closure or mesh onlay for large defects is successful.

Obturator hernia

Obturator hernias are approached abdominally and can be repaired laparoscopically. If the hernia content is difficult to reduce, incision of the obturator membrane at the inferior margin will lessen damage to the obturator vessel or nerve. Mesh closure is necessary for a tension-free repair. The other side must be viewed to preclude problems with a contralateral hernia.

Sciatic hernia

A transperitoneal approach is used in the event of incarceration. Avoiding neurovascular injury during reduction and repair requires careful attention posteriorly and inferolaterally for the suprapiriform hernia, superomedially for the infrapiriform hernia, and medially for the subspinous hernia. The defect is closed with prosthetic material.

A transgluteal repair can be used if the diagnosis is established and the intestine is clearly viable. The patient is placed prone, and the incision is extended from the hernia toward the greater trochanter. The fibers of the gluteus maximus are spread to expose the piriformis, the gluteal neurovascular bundle, and the sciatic nerve. A prosthetic patch closes the defect between the piriformis and the iliac or ischial bone.

Perineal hernia

A transabdominal approach with prosthetic closure is the preferred approach in the repair of perineal hernias.

Surgical Repair of Gastroschisis, Omphalocele, and Other Defects

Gastroschisis and omphalocele

The morbidity and mortality associated with omphalocele or gastroschisis in infants over the past 35 years has greatly decreased because of better preoperative and postoperative care. Specifically, these improved outcomes are secondary to advances in neonatal ventilator care and the development and use of total parental nutrition during the period of transition to normal bowel function.

Patients with syndromic omphaloceles have had only modest increases in mortality secondary to the unchanged severity of their associated defects. The improvement in this population results from prenatal recognition, earlier prenatal transport to pediatric surgical referral centers, and enhanced perioperative care.

Perioperative considerations

The greatest loss of contractility and mucosal function of the bowel and the fibrous coating of the bowel in gastroschisis occurs late in gestation. Delivery of infants with prenatally diagnosed abdominal wall defects can be via vaginal or cesarean delivery; neither method has a clear advantage over the other.

Preterm induction after ensuring lung maturity may be advantageous in cases of gastroschisis where serial imaging of the bowel reveals increasing dilation suggestive of a restrictive defect. To avoid damage to the sac from labor and delivery, elective preterm cesarean section is no longer recommended for infants with large omphaloceles.

Placing the infant up to the axillae in a sterile plastic bag maintains sterility, prevents evaporative water loss, and decreases heat loss. Infants with gastroschisis can be placed on their right side until silo placement is complete to prevent vascular compromise from twisting or kinking of the fascial edge. Although recommendations in the literature vary, the trend is toward universal silo placement and gradual reduction. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given, most commonly ampicillin and gentamicin.

The inflamed peritoneal and intestinal capillary membranes stabilize in 12-18 hours after surgery, and the fluid requirements then markedly decrease. When the capillary membrane stabilizes, exogenous albumin may be administered to elevate serum levels to 2.5-3 g/dL. The testes may be extracorporeal and should be placed near the processus vaginalis, because testicular proximity is a critical factor in the formation of the gubernaculum.

Management approaches

The major challenges in gastroschisis are reduction of the inflamed viscera into the abdomen and maintenance of effective nutrition. The two major problems in the management of omphaloceles are (1) closure of the defect without undue tension and (2) treatment of associated anomalies, particularly cardiac defects and pulmonary hypoplasia. Associated anomalies must be stabilized swiftly before operation.

Primary closure of fascia and skin is the best approach for omphalocele and gastroschisis. However, increased intra-abdominal pressure from immediate reduction can compromise ventilation and lead to abdominal compartment syndrome with inferior vena caval compression, intestinal and renal hypoperfusion, and lower-extremity edema.

Enlargement of the abdominal cavity by stretching the abdominal wall, decompression of the stomach and irrigation of the intestine and colon to remove meconium, and postoperative use of ventilators and muscle relaxants frequently can facilitate successful primary closure. The sac is removed at the fascial edge. Umbilical artery or vein catheters can be transposed to an extraumbilical location for postoperative monitoring and fluid delivery. Vigorous attempts to decompress can cause intestinal tears and should be avoided.

Nonoperative management of gastroschisis, also known as plastic closure, is an alternative to conventional primary operative closure or staged silo closure. Although it is considered safe, nonoperative management is nonetheless associated with an increased incidence of umbilical hernias. [48]

Intra-abdominal pressure measurements help prevent intra-abdominal compartment syndrome. Excessively high pressures mandate immediate conversion to a Silon chimney sutured to the skin or the fascial rim (see the image below). The gradual reduction of liver and intestine represents an improvement over previous methods, and most pediatric surgeons use this technique. Fascial and skin closure occurs after complete reduction of contents into the abdomen, which usually occurs over 3-7 days.

An alternative technique for omphaloceles is abdominal binding. With sequential pressure, the viscera can be reduced into the abdomen over a similar period, followed by delayed primary closure. During final abdominal closure, a prosthetic patch of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) or biosynthetic mesh can bridge the gap between the rectus muscles. Tissue expanders can facilitate this stage. [49] Orchiopexy can be performed for cryptorchid testes at the time of final closure.

Intestinal atresia is common. Anastomosis at the closure operation is sometimes possible, depending on the degree of bowel thickening. Repair after a 4- to 6-week period of bowel decompression and parenteral nutrition is preferable, but this is contraindicated in the face of a large proximal-distal discrepancy or necrotic intestine. The combination of stomas and prosthetic material can be avoided in almost all patients.

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

The diagnosis of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome should be suspected in a large neonate with macroglossia. As these infants are at risk for severe hypoglycemia, close monitoring and early administration of glucose can prevent the serious sequela of hypoglycemia.

Pentalogy of Cantrell

Pentalogy of Cantrell is a malformation of the upper abdominal fold characterized by an anterior diaphragmatic and pericardial defect, a short bifid sternum, and cardiac defects associated with an epigastric omphalocele sac or hypotrophic epigastric skin. Temporary coverage of the omphalocele during evaluation of the cardiac defects will allow subsequent complete repair of cardiac, diaphragmatic, and pericardial defects.

Vesicointestinal fissure or cloacal exstrophy is a malformation of the lower fold defined by an inferiorly sited omphalocele, exstrophy of the cecum between the hemibladders, diastasis of the symphysis pubis, a short distal colon, no rectum, a shortened small bowel, and occasional meningosacral anomalies. These infants can survive after multiple corrective intestinal and urinary tract procedures.

Umbilical remnants

Mucosal biopsy provides diagnostic confirmation of the clinical suspicion. A patent omphalomesenteric duct requires prompt excision to prevent intussusception. About 50% of children with external mucosal remnants will have an additional component within the abdomen. Urachal remnants should be excised locally at the umbilicus and followed caudally for a short distance toward the dome of the bladder, where they should be sutured, ligated, and divided.

Long-Term Monitoring

For patients with easily reducible hernias or with hernias found upon physical examination, follow-up visits with the general surgeon should be scheduled within the 1-2 weeks following the procedure. Patients with umbilical hernias may be discharged with close follow-up care if the defect is less than 2 cm in diameter and the hernia is not incarcerated or strangulated.

Accurate postoperative instruction and easy access to care (if problems arise) are as effective as a full postoperative visit after routine inguinal hernia repairs. Patients should be educated to avoid those activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure and instructed to return if they note an irreducible hernia, increased pain, fever, or vomiting.

-

Large right inguinal hernia in 3-month-old girl.

-

In this baby with gastroschisis, bowel is uncovered and presents to right inferior aspect of cord.

-

Hernia of umbilical cord.

-

Note translucent sac in baby with large omphalocele. Umbilical vessels attach to sac.

-

Hernia content balloons over external ring when reduction is attempted.

-

Hernia can be reduced by medial pressure applied first.

-

Infant with Silon chimney placed in treatment of gastroschisis.

-

Atrophy of right testis after hernia repair. Note adult-type incision.

-

Iatrogenic cryptorchid testis in child. Taking care to position testis in scrotum is integral part of completion of hernia repair in boys.

-

Erythematous edematous left scrotum in 2-month-old boy with history of irritability and vomiting for 36 hours. Local signs of this magnitude preclude reduction attempts.

-

Testis at operation in 2-month-old boy with history of irritability and vomiting for 36 hours. Capsulotomy was performed, but atrophy occurred. Patient also required bowel resection.

-

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt, decreased activity, and acute scrotal swelling in 6-month-old boy.

-

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt, decreased activity, and acute scrotal swelling in 6-month-old boy. Abdominal radiograph shows incarcerated shunt within communicating hydrocele. Repair of hydrocele relieved increased intracranial pressure.

-

Bassini-type repair approximating transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascia to iliopubic tract and inguinal ligament.

-

Anatomic locations for various hernias.