For parents of black children in the US, where bigotry continues to take people’s lives and freedom, talking about race is often not optional. But acknowledging and naming race in conversations with children is something all parents must do, experts say—early and often.

Nevertheless, many parents, especially white parents, still avoid the topic of race, and teach children that it’s a rude, taboo topic—believing perhaps that not talking about skin color will make it seem irrelevant.

That’s tragically wrongheaded, says Brigitte Vittrup, a psychologist specializing in child development at Texas Woman’s University: “We have to talk to our kids about it, and we shouldn’t be afraid that we’re bringing something up that they haven’t discovered, because they have.” Science has shown that kids recognize skin colors as toddlers, and develop ideas about races as superior or inferior by the time they start primary school. They may also be subjected to ideas about racial stereotypes by their classmates and preschool teachers.

Vittrup illustrated how common the habit of avoiding the topic of race is among white parents in a recently published study. She surveyed 107 white mothers of children in America aged 4 to 7 about whether and how they approached race with their kids. “Most mothers indicated the topic was important to discuss,” she writes in the introduction to her work. “However, many reported having no or only vague discussions.” Two out of three mothers—70%—espoused a philosophy she described as “colorblind” or “colormute.”

Two other psychological studies suggest that most children, including children of minority races, have absorbed the message that race is a taboo topic. These experiments asked kids to play a variation on Guess Who—with the games rigged so that asking questions such as “Is the mystery person black?” or “Is the person white?” would allow the players to ask far fewer questions and win. Younger children, aged 8 and 9, did better at the game than older children, aged 10 and 11. Many of the older children explained to researchers that using race to identify which person was being described would be rude, or an expression of prejudice or racism.

There’s another reason for parents concerned about racial equality to talk to their kids about race: Silence on the topic leaves unchallenged the ideas children pick up from other sources, and assumptions they reach based on the structural and historic racism they observe around them. This tendency was demonstrated in a study from University of Texas, Austin conducted in 2006, in which psychologists asked 76 children aged 5 to 10 to choose a possible reason why all US presidents until that point in history had been white.

One in four students agreed with a proposed argument that it was illegal for black people to become president, having apparently arrived at this conclusion based on the evidence they’d gathered independently, without a discussion about race.

Here’s what parents and teachers can do

There’s evidence that parents who make race an acceptable household topic help their children develop more positive attitudes about people of other races—but it’s not an easy conversation for many parents to broach.

One objection is that discussing it gives weight to the notion of race, which is rightly dismissed as a social construct—a culturally created idea, not a biological fact. But that doesn’t mean it can be ignored in a society built around it, says Sachi Feris, a co-founder of the organization Raising Race Conscious Children in Brooklyn, New York, which offers online and in-person workshops for parents and caregivers.

“Yes, we absolutely believe race is a social construct,” she tells parents. “And we also believe race is real, based on the different experiences people have because of these social constructs. And if we don’t name them, we can’t do anything to shift the power structure and break them down.”

Feris and her co-founder, Lori Taliaferro Riddick, offer this practical advice, and additional strategies on the organization’s website:

Start naming and identifying race as part of your description of our world

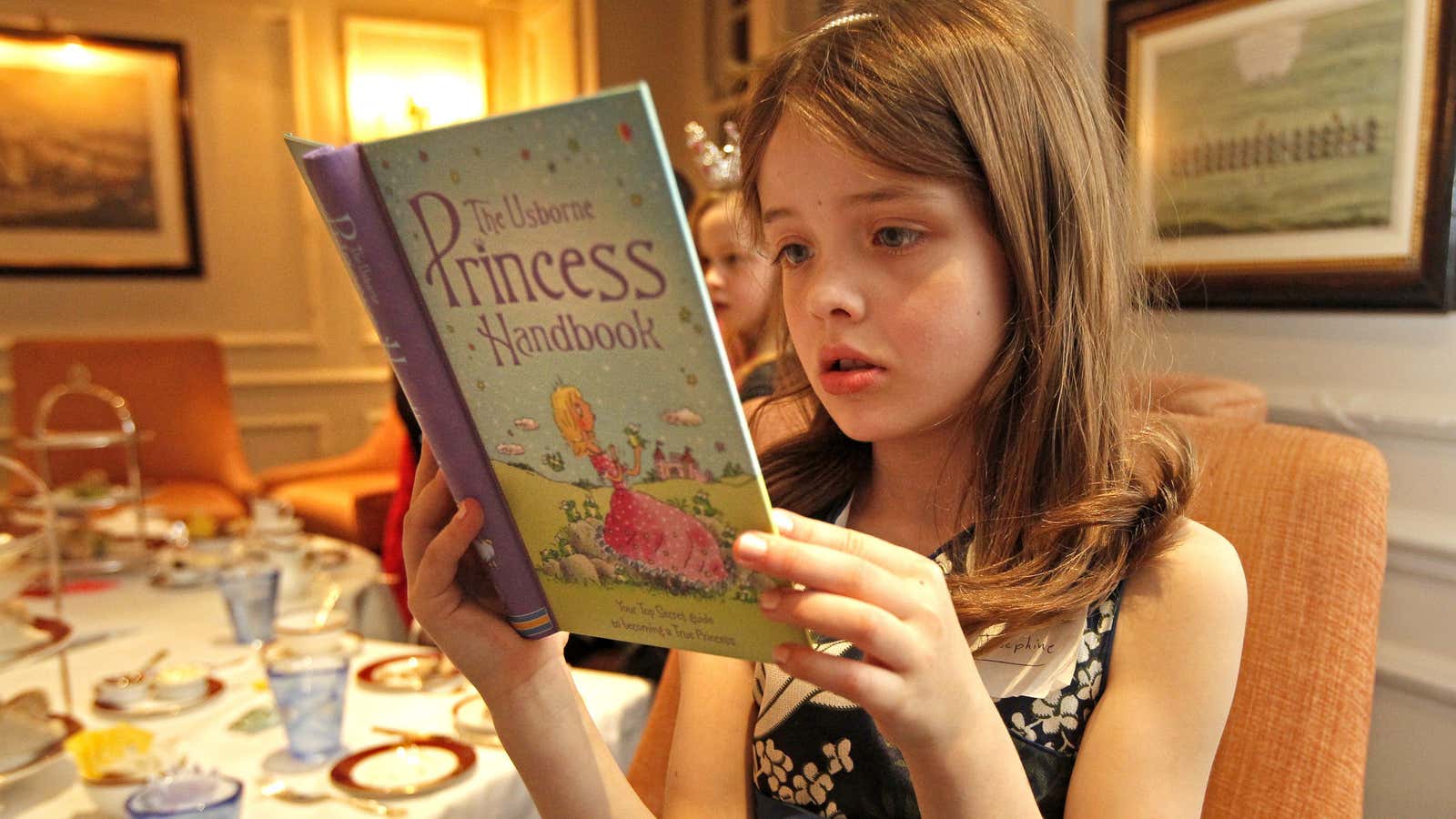

When you’re looking at picture books, watching TV, or viewing advertisements, begin including skin color and race in the ways you describe the world, Feris explains.

“A lot of what people talk to kids about is color, like red trucks and blue cars,” she notes, so introducing race into those conversations feels natural. Parents can say, ”Look, here’s a picture of a little girl. She has pale skin. We call that ‘white.’ This little girl has brown skin. She might call herself ‘black’ or ‘African-American.'”

Importantly, naming race should happen in moments that adults can control, Riddick and Feris suggest, not just when there’s a race-related incident at school or a crisis in the news, such as a police shooting.

To push past your own discomfort, practice

Race should be part of everyday conversations, Feris advises. But for people who were raised to avoid any mention of race, that can feel deeply wrong, or even impossible. (A survey from MTV recently found that millennials, who overwhelmingly profess a belief in equality, also find talking about race a challenge.) Feris assures parents that it gets easier with practice.

In workshops, parents role-play with each other, imagining they’re speaking to their baby or toddler. Doing this shows them that they can do it—and proves to them that they should.

Teach the etiquette of when and where to discuss race

Parents frequently worry that their child’s race awareness will be perceived as rude in the wider world, where it’s still not the norm.

Feris handles that concern with her own child by explaining that we don’t point to people and say something about their appearance or characteristics, just as we wouldn’t do that regarding a person’s hair color or size, even though we notice these traits. We also generally refer to people by their names, not what they look like, whether or not they are present. She says, “We have to ask respectful questions if you want to engage in conversations about race.”

What’s more, she explains, it’s helpful to distinguish between public and private spaces and conversations, and to make children aware that: “The words one uses in the privacy of her/his home versus in public may sound different.” Home is the place to encourage children’s questions about race—although the topic need not be completely avoided in a crowded subway car.

Attend a diverse range of cultural events, but talk about race when you do

Exposing children to other races in books and at cultural events is a common—and smart—piece of advice, but Feris believes one should go further by drawing attention to that intentional effort.

Don’t pretend it’s a coincidence that we’re going to an unfamiliar cultural event in a distant neighborhood today. If the aim is exposure to and celebration of a different race or culture, make that point. Then talk about it.

Call attention to messages you question and reveal your own struggle with biases

Don’t ignore images or messages you find unacceptable or stereotypical, or your own biases or prejudices. Talk them out with your children, instead.

Andrew Grant-Thomas, a director of programs at the Interaction Institute for Social Change in Boston suggests that there’s a real value to letting your child see you confronting and working to overcome your own biases. Discuss what experiences and ideas have influenced your perception of race.

Celebrate your own family’s race and identity

“Know and love who you are,” Grant-Thomas writes. That means teaching your child about the racial, ethnic, and cultural groups your family identifies with. But don’t sugarcoat the past: “Talk about their contributions and acknowledge the less flattering parts of those histories as well.”

Celebrating race is particularly important for children of minority races. When they play down race, as they are socialized to do, it not only allows inequities to stand, but it makes it difficult for them to develop a positive racial identity, research has found.

Make race a part of children’s investigations of “fairness,” and teach them to take action

Fairness is a concept kids grasp early in life. The unfairness of prejudice and structural racism can be seen through that lens. Once they grasp the problem, start planning action, says Grant-Thomas: “Whenever possible, connect the conversations you’re having to the change you and your child want to see, and to ways to bring about that change.”

Feris agrees. When encountering a book that lacks diversity, for example, she might ask, “Should we write a letter to the publisher and tell them what we think?” Even simpler, a child might want to call grandma to make her aware of this inexcusable situation.

These may be small steps, but they lay the foundation for a young mind to engage with more complex issues—in time.