Avoid Accidents With Better Multi-pitch Communication

Use this expert advice to never lose touch with your partner on a long route.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

All multi-pitch climbers have experienced it: Your partner climbs around an arête or over a roof or away into a howling wind, and suddenly she’s out of sight for the rest of the rope-stretching pitch. You continue feeding out slack, but then there’s a long pause with no rope movement. You call out but get no response. Is your partner building an anchor? Is she stuck at a crux? Did she stop to take a photo? It doesn’t matter how well you’ve got your technical and movement skills dialed, when communication breaks down between you and your partner, you’ve got a problem. I spoke with IFMGA guide Eli Helmuth to outline planning and technique strategies that will help you avoid this issue in any situation.

Minimize Communication

The less you need to communicate, the less of an issue communication is. “Keep it to a minimum to minimize confusion,” Helmuth says. A competent belayer doesn’t need instruction, so there’s no need for the climber to narrate his ascent. The only commands necessary are “off belay” and “on belay.” Helmuth tells clients that the only thing they will hear from him is their first name followed by “off belay.” “I’m going to yell really loudly, and they might not understand what I’m saying, but it’s the only thing I’ll be saying so they should get it.” The same goes for putting your partner on belay at the top of a pitch. Let your partner know that he’ll be on belay within 30 seconds of the rope going tight. That means you shouldn’t start pulling up rope until you have your belay device ready and you’re prepared to put him on belay. Yell “off belay,” wait a few seconds for your partner to take the rope out of the belay device, then start pulling the rope vigorously. If you feel resistance, yell a second time, wait 15 seconds, and then start pulling fast again. That’s an excellent second indication if your belayer is unsure.

Direct Your Voice

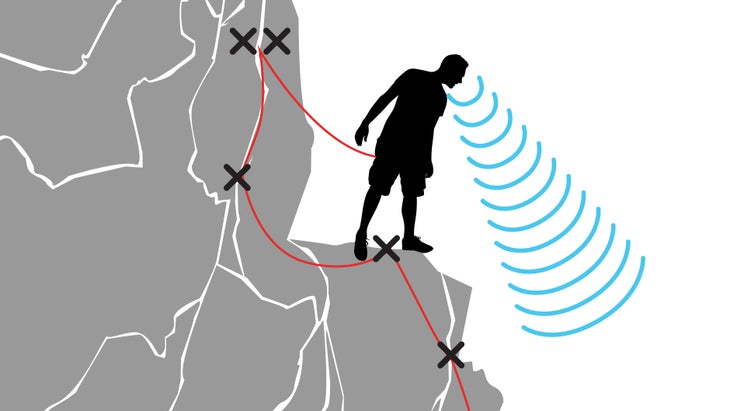

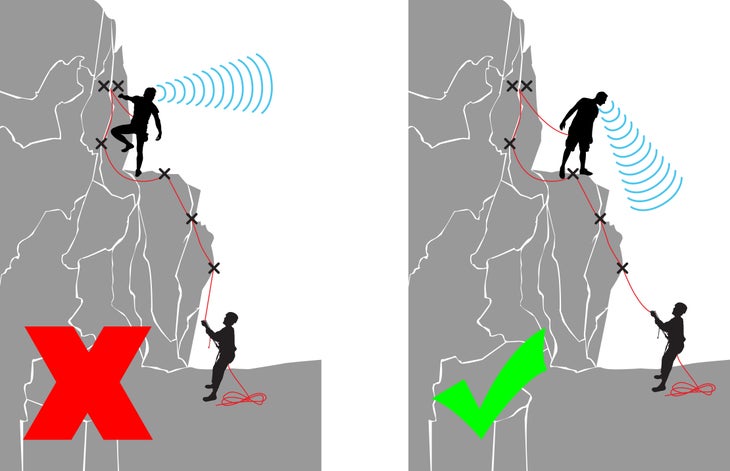

With proper technique, you can almost always communicate successfully from up to 60 meters away, but you have to be smart about it. The biggest issue Helmuth sees when he’s training guides in Colorado is that they don’t yell loudly enough. “Or they yell uphill [above left] instead of turning around and yelling downhill toward the climber below [above right].” In order to optimize the direction of your voice, connect yourself to the anchor with an extendable clove hitch that will allow you to move around instead of being two feet from the anchor. Position yourself so you can look over the edge of your belay ledge and see your partner. You partner should do the same, extending himself from the lower anchor. Once you have eye contact, aim your voice at him. Don’t yell into the rock or up the cliff. Point your mouth at your partner, cup your hands around it like a makeshift megaphone, and yell loudly. Keep the message short and pronounced, not too wordy or confusing.

If the day is particularly windy, or the route takes a major turn around a corner, it’s possible to avoid problems by doing shorter pitches. “Our AMGA training tells us to put ourselves in voice range whenever in doubt,” says Helmuth. “Which often means ignoring advice in guidebooks about where to put the belay and basing it on weather and other factors instead.” Without extensive beta or having been on the route before, you won’t be able to plan these belay stances in advance, so use your best judgment. If you’re about to lose sight of your partner over a bulge or around an arête, build a belay. Err on the side of caution and build an anchor when you have the opportunity (and the gear) instead of finding yourself on a 20-foot section of runout face climbing with no anchor options in sight.

Handheld Radios

In particularly adverse conditions or on routes with limited belay stance options, handheld radios can be a valuable communication tool. Leave the ground with full batteries (or full charge) and stay on the same channel as your partner. Keep the radio in a spot that’s accessible even when you’re climbing, and keep the volume loud enough so you can hear it over environmental factors (wind, water, etc.). Helmuth finds the need for a radio is rare, and he recommends dialing in other communication techniques first, before relying on a radio for communicating. He says, “Make it a priority to be as clear as you can be, get over the edge, and direct your voice.”

Another Option

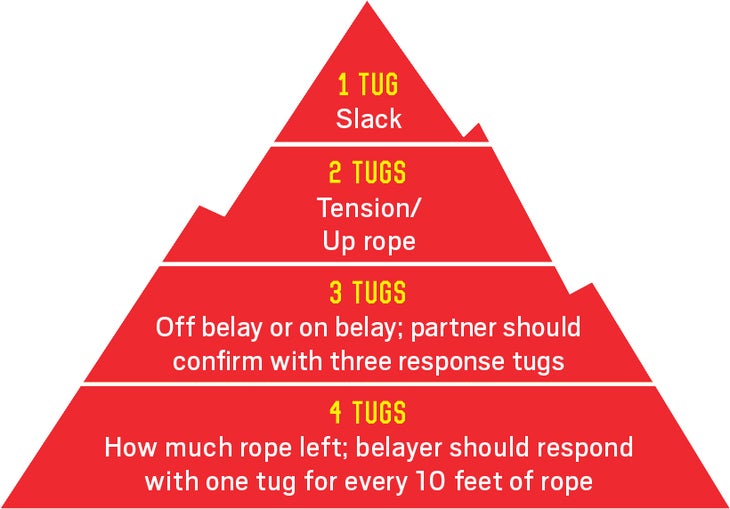

The Marhold Tug

Developed by Trenton Marsh and Bucky Buckhold, and published in the Adaptive Climbing Manual (Paradox Sports, 2015), this system allows deaf climbers to communicate using a series of rope tugs to relay basic information between climber and belayer. The commands are based on the number of syllables.

Helmuth advises using this or any tug system with caution: “If a belayer is looking for tugs, it’s too easy to take any rope-pulling motion as an off-belay signal.” For clearest communication, Buckhold recommends using a thin static line attached to the back of the climber’s harness. Don’t clip this to any pro to minimize maybe-tugs and communication-dulling rope drag. It’s also important to make tugs sharp and deliberate and to agree on commands before starting up the wall. The tug system doesn’t leave much margin for error.