Abstract

The author identifies a critical juncture in the global economy: the emergence of a new production system pivoting on “open innovation” and knowledge networks that are, however, exclusive in the context of rapidly increasing poverty and socio-economic polarization worldwide. The chapter develops a critical agenda to make use of: (1) theories about (economic) knowledge generation and networks to develop social knowledges by dissolving frictions of difference and constructing an inclusive system of collaborative work; and (2) the market itself to adapt new corporate strategies to social ends in the course of sustaining, if not augmenting, productivity. The chapter envisions a system of mediated crowdsourced project work drawing support from the public and private sectors. Precedents for various components of the agenda exist; the agenda is to imbricate such projects in a holistic approach to achieve social as well as economic change by reconfiguring the values that govern everyday life.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Crowdsourcing

- Open innovation

- Networks

- Knowledge

- Segregation

- Social change

- Communication

- Social enterprise

Divergent Trends in the New Millennium: Setting an Agenda

Taking stock of changing realities, in this chapter I take note of an emergent production system around the turn of the twenty-first century that pivots on new approaches to innovation and, relatedly, on open networks to access dispersed knowledges. At the same time, it is sensible to recognize pressing social problems associated with dramatically increasing socioeconomic polarization and precarious livelihoods worldwide, as well as persistent problems of segregation that inform the nature of exclusions. Although the new system of production is lucrative for firms, its contribution to social problems has been negative at best because new networking strategies remain exclusive, while being highly exploitative in new ways. At this critical juncture in the global economy, my aim in this chapter is to bring a sociopolitical agenda to new economic realities that would service economic agents and goals while developing a means to extend living-wage and stable work in knowledge networks to diverse people, and in the process dissolve frictions of difference through collaborative work relations. Based on a critical synthesis of information drawn from case studies across wide-ranging literatures ( economic geography and sociology; social theory; and business, management, and information science), I conceptualize a strategy for making use of new networking strategies that is inclusive and shaped by social goals .

The ensuing argument begins with conceptualizing a reversal of the usual instrumentality of the social for the economic. I contextualize the agenda in terms of the above-stated critical juncture in the global economy, namely new types of economic knowledge networks that reap enormous rewards for corporations without, however, attention to dire and worsening social needs and problems. I conclude this section with a call for imbricating social knowledges with an understanding of economic knowledge networks. In the next section I discuss a particular social problem, segregation, which spatially expresses exclusions in everyday life. Crucially, segregation is driven by ignorance; therefore, constructively engaging segregation requires targeting ignorance by developing social knowledges—per the frame of this edited collection, specifically in the context of knowledge networks. I turn then to the literature on knowledge generation and exchange in economic-oriented literatures to cull insights regarding requirements for the development of socially oriented issues of trust and mutual respect that underpin collaborative project work . One limitation of this literature is that it presents a faceless landscape of actors, and thereby elides issues of difference. In light of my goal to conceptualize the proactive construction of diverse and inclusive knowledge networks, I then draw insights from the business, management, and information science literatures on potential problems of the frictions of difference in on-the-ground as well as virtual workplaces. While useful, this literature nonetheless lacks attention to social goals—back to the problem of the usual instrumentality of the social for the economic—and thus requires attention to the multidimensionality of problems. As I will elaborate, I envision the construction of a web of inclusive knowledge networks in what I call “mediated crowdsourced project work,” supported by government and other organizations to ensure continual, living-wage employment in ephemeral networks that form, dissolve, and form anew with different membership to meet the requirements for particular constellations of expertise across projects. At the outset I envision such a project at the metropolitan scale where field research can identify the domain of skills in local populations, allowing for such projects to extend beyond localities over time. My aim is to develop a critical agenda—as opposed to a blueprint or policy brief—to clarify the issues, the logics, and, moreover, the need to chart a new course, while avoiding the replication of existing ills. The vision here derives analytically from a critique of the existing system and a problematization of those new features of the production apparatus that require reconfiguration to achieve social as well as economic goals.

Despite this admittedly ambitious agenda, precedents for discrete components nonetheless exist in various contexts. Open network strategies such as crowdsourcing connect firms seeking expertise or intellectual property with individuals who may be disassociated from firms (although not in association with stable, living-wage jobs). The U.S. government has supported the formation of open networks constituted by firms (although not open networks that draw from a skilled population of workers who may be disassociated from firms). Governments outside the United States support enterprises that privilege social objectives and community well-being over economic goals (although not in connection with new types of knowledge networks). Field research has identified skill sets among marginalized, populations (although not in association with new approaches to production and not necessarily remunerative). The novelty of the agenda I develop, then, lies in the imbrication of components among discrete projects in a holistic approach to achieve both social and economic change.

The Nature of Economic Networks in Relation to Social Issues

Analyses of economic networks for goods and services commonly cast people as instrumental to the effective functioning of networks. The social capital that accrues to such networks is seen to result in productivity, innovativeness, resilience, and the like.Footnote 1 This relation between people and networks, with the former serving the latter, is sensible in the context of neoliberal society, which encompasses researchers as much as their subjects and objects of study. As critical philosopher and historian Michel Foucault (2004/2008) argued, neoliberal practices transform the social into economic opportunity, reflected in the academic conceptualization of social relations as instrumental to economic goals.

I aim to conceptualize a reversal of the usual relation between the social and the economic to engage specifically how economic knowledge networks can enhance social relations. How, then, might economic networks contribute to social change? The question appears to counter neoliberal logic. However, as research on economic networks has pointed out, constructive social relations in the arena of production and innovation depend on effective collaboration, trust, and mutual respect (Bourdieu , 1986; Glückler, 2005). Thus, the process of achieving social goals embeds economic goals (Cantener, in this volume). Such nesting is not, however, necessarily implicated when the goal is conceived economically because economic goals often are achieved at the expense of the social, notably labor.Footnote 2 The overall strategy I offer aims at subverting the usual logic of instrumentality by rendering economic effectiveness useful for social relations without, however, negating the importance of social relations for economic performance. I advocate a counter-conduct Footnote 3 that works from within the dynamics of the system, consistent with Foucault’s (1996, p. 387) provocative point that effective critique and resistance “relies upon the situation against which it struggles” and is immanent to the system of governance. Per Foucault (1996, p. 386) resistance “is not simply a negation, but a creative process,” which can take shape in an agenda for positive social change.

A Critical Juncture in the Global Economy: Open Innovation and Networks

The impetus for a normative agenda is recognition of a critical juncture in the global economy in which an emergent mode of production associated with new networking strategies reaps considerable rewards for firms and shareholders, but exacerbates already precarious ways of earning a living and, more generally, inequality in the context of deepening socioeconomic polarization worldwide (Beck, 1999/2000; Standing, 2011). The aim is not to dismantle existing corporate strategies, an unfeasible strategy, but rather to conceptualize ways to make use of them by reconfiguring goals to privilege the sociopolitical without jettisoning the economic—admittedly difficult, but plausible.

The emergent system of production is characterized overall by openness (Ettlinger, 2014) regarding two overlapping systems: innovation, and networks to access labor. Networks connect with innovation as a means by which firms access expertise and intellectual property. However, networks also enable firms to access labor for non-innovative yet menial activity, and the processes for connecting with this labor market differ.Footnote 4 In keeping with the theme of this volume, my focus in this chapter is on networks in relation to innovative activity, specifically knowledge networks.

Novel forms of knowledge networks have evolved in the context of what has been termed open innovation in the business literature. The term was coined in 2003 by former corporate manager and Berkeley scholar Henry Chesbrough (Chesbrough, 2006a, 2006b; Chesbrough , Vanhaverbeke, & West, 2006). The first survey of open innovation was conducted in 2013, encompassing large firms in the United States and Europe with sales of more than 250 million dollars; results showed that over three quarters of the firms actively pursued open innovation strategies and, moreover, support for open innovation among top managers is increasing (Chesbrough & Brunswicker, 2013).

Open Innovation and Networks

Open innovation refers to the eclipsing of a longstanding tradition of in-house innovation by new practices whereby firms develop innovations on the terrain of interorganizational relations. Although firms externalized production under the regime of flexible accumulation beginning around 1980 in the United States and Britain and more recently in continental Europe, innovation nonetheless largely remained an in-house activity. Around the turn of the twenty-first century, firms began externalizing innovation , in part as deepening vertical disintegration (associated with flexible accumulation) gradually produced unanticipated benefits for large firms, namely the possibility of learning from suppliers and making use of innovations they developed—a trajectory facilitated by the increasing ubiquity of personal computer hardware and software (Gawer & Cusumano, 2002, p. 5). Further, as availability of venture capital from venture capital firms declined over the last decade, many large firms internalized venture capital programs (corporate venture capital, CVC) to invest in small to medium-sized firms (SMEs) to develop innovations pertinent to their (the large firms’) competencies (Van de Vrande, Vanhaverbeke, & Duysters, 2011).Footnote 5

Push factors for open innovation included the increasing costs of technology development, which have prompted firms across the size spectrum to develop strategies to spread expenses to reach beyond their boundaries for problem solving and intellectual property. Further, many large firms lack sufficient internal expertise, in part as a vestige of lean management in the 1980s, when firms laid off many personnel, including researchers; accordingly, firms increasingly access expertise externally (Chesbrough, 2006a, p. 190). The goal set by Proctor and Gamble’s newly appointed chief economic officer in 2000 is telling: to acquire 50 % of the company’s innovations from external sources (Huston & Sakkab, 2006).

Beyond the development of innovative capabilities among suppliers in the context of relations between large and small firms, open innovation also entails interfirm relations among large firms that interlink business models based on new innovations, notably in industries that produce multi- component products (Chesbrough, 2006a, 2006b; Cooke, De Laurentis, MacNeill, & Collinge, 2010; Gawer, 2009; Gawer & Cusumano, 2002). The main imperative in open innovation is to continually move to new innovative activity in concert with other firms producing related products and services.Footnote 6

The management of innovation across the spectrum of firms practicing open innovation has occurred in the context of the development of a relatively new demand environment: customized demand , which requires combinations of expertise that cannot be anticipated (Goldman, Nagel, & Preiss, 1995). Although, in principle, firms under such circumstances can continually add to their repertoire of skill through mergers, acquisitions, and continual hiring of experts, the high costs of such a strategy often prompt firms to look instead for expertise among external sources (Grant, 1998). From the vantage point of structural hole theory, linkages to an increasingly broad range of organizations increase social capital, provide a means by which individual firms can overcome structural gaps (Burt, 1992; Burt, Hogarth, & Michaud, 2000; Garrigos-Simon, Alcami, & Ribera, 2012), and enhance innovative capacity based on increasingly diverse knowledges (Frey, Lüthje, & Haag, 2011; Poetz & Schreier, 2012). Agility, defined in this context as the capacity of firms to tap external resources efficiently and rapidly, is a key asset of organizations (Goldman et al., 1995; Greis & Kasarda, 1997).Footnote 7 Outsourcing in the context of open innovation, even if exploitative, is prompted at the outset not by lowest cost of labor and products in externalized production, as in a Coase (1937)-inspired model of economic activity, but rather by the need to incorporate expertise external to a firm in projects that crosscut firms, as in a Hayek (1945)-inspired conceptualization. Per Hayek (1945), the world constantly changes, requiring an effective means of culling dispersed knowledges. Assuming all individuals possess unique knowledge, a central problem for Hayek was how dispersed knowledges might be accessed. The contemporary answer to Hayek’s problem regarding innovation is open networks, in contrast to the tradition of relatively closed organizational forms (Lazega, in this volume). Whereas just-in-time manufacturing networks associated with flexible production tended to evolve as relatively closed with “strategic bridges” (Burt, 1992, 2005) forged between networks to facilitate flows of new information, Web 2.0 information and communications technologies (ICTs) have facilitated the development of open networks that draw from dispersed knowledges across firms (Garrigos-Simon et al., 2012).

Crucially, firms have opened their boundaries in the realm of innovation not only to other firms, both small and large, but also to freelancers “on the street,” who may not necessarily be associated with firms and conceivably may even be unemployed. The governing apparatus of this labor market is crowdsourcing, which is one of several short-run avenues by which firms ensure fast profitability to complement long-term investment strategies and meet the demands of shareholders. Other short-run avenues include licensing in ready-to-go innovations to avoid their expense as well as time to invention and innovation; licensing out warehoused inventions that have not been commercializedFootnote 8; and partnering with universities, think tanks, and non-governmental organizations (Chesbrough, 2006a; Fabrizio, 2006).

Companies crowdsource by sending out open, electronic calls for inventions or expertise when problems emerge and require solution. For example, in 2002 Proctor and Gamble wanted to find a way to print edible pictures on each potato chip in a Pringles can; their electronic call was answered by the owner of a small bakery in Bologna, Italy, who had invented a way to print edible pictures on cakes and cookies; more generally, Proctor and Gamble has developed a strategy it calls “Connect + Develop” to replace the more traditional mentality of in-house research and development (Huston & Sakkab, 2006). Other companies orchestrate high-stakes online competitions as a growth strategy to access inventions that would enhance core competencies. Cisco Systems, for example, arranged an online competition for an invention related to its core competency in internet technology in 2007, offering a prize of 250,000 dollars to the winner; 2500 inventors across 104 countries competed, with rules stipulating that the winner would sign over the commercial rights of the invention to Cisco (Jouret, 2009). This one-time cost was offset considerably by the long-term billion-dollar business that Cisco launched using the winning invention as a platform.

Many firms now outsource crowdsourcing, giving rise to a new breed of firms that connect seekers (firms looking for new technology or expertise) with solvers (firms or individual actors with intellectual property or expertise who may be disassociated from firms)—the contemporary answer to Hayek’s concern for how to access dispersed knowledges. Useful classifications of these mediatorsFootnote 9 exist (e.g., Feller, Finnegan, Hayes, & O’Reilly, 2009),Footnote 10 but the rapid evolution and internal diversification among these firms render the classifications insightful mainly in clarifying an initial division of labor. For example, some of these firms specialized in connecting seeker firms with experts selling existing intellectual property, while others connected seekers with experts selling their expertise to solve problems; some specialized at the outset in demand-driven activity such as classifying and cataloguing problems that solvers search, while others focused on supply-side activity such as finding solutions sought by firms. Most of these firms gradually have diversified internally, developing an array of activities and services to complement the kind of activities that characterized their niche as they emerged at the outset as a secondary market for innovation .

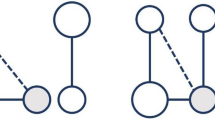

Whereas all the above-mentioned mediators broker networks characterized by a hub-and-spoke structure in which the mediating firm is the connector but the network of individual solvers (people) lacks connectivity, another model of open networks entails networks of solver firms (not people) that collaborate relative to customized demand. In this latter system one firm receives customized orders from seeker firms and subsequently coordinates expertise amongst solver firms in ephemeral networks. Firms coalesce temporarily in projects to combine expertise to solve a problem; networks dissolve following completion of projects, and form anew with new memberships relative to the required expertise. This type of solver network is exemplified by the Agile Web, a virtual corporation established in 1995 and constituted by 20 small-to-medium-sized manufacturing firms that were selected from a population of over 700 prescreened firms in northeastern Pennsylvania; by 1999 it obtained over 50 million dollars in orders (Sheridan, 1993, 1996). In 2000, G5 Technologies, a company in New Jersey, acquired the Agile Web to enhance its array of collaborative business services and internet-based software technologies; as a subsidiary, the Agile Web remained intact, providing collaborative product design and manufacturing solutions (PR Newswire Association LLC, 2000). Similarly, KICMS is an association established in South Korea in 2004 that coordinates collaboration on research among large numbers of SMEs (around 4000), while also providing consulting services and assistance to the SMEs in developing markets (Lee, Park, Yoon, & Park, 2010).

To date, then, there are firms that access innovative expertise among individual people (not firms) in a hub-and-spoke approach in which there is no collaboration among solvers, and there are firms that access expertise among firms (not people) that engage in collaborative problem solving and temporarily coalesce in networks. The former case represents a lucrative model for firms that contracts with people, not firms, but is hardly a source of remunerative, living-wage jobs; each contest has one or a few winners and often thousands of losers who self-fund, and moreover, sign away their intellectual property rights when submitting their contributions. The latter case represents an effective organizational model to meet economic (not social) goals, and the customized orders reach firms, not individual people. Consider, then, the possibility of combining elements of each of these types of knowledge networks to constitute a hybrid system that serves social as well as economic goals.

Making Use of New Knowledge Networks to Develop Social Knowledges

I am interested in the proactive construction of one type of activity: mediators, which may be non-profit and at least partially government funded, that could connect firms as well as other organizations (e.g., government-funded and non-profit organizations, academic institutions) with appropriate networks of solvers who are people, not firms, to collaborate in remunerative, problem-solving activity. Based on information drawn from numerous cases studies, I develop a normative argument about the social as well as economic potential of this organizational approach to innovation that I term mediated crowdsourced project work. At this critical juncture in the global economy I am interested in how new approaches to accessing expertise in open networks, notably crowdsourcing, might be constructed so as to erode precarious conditions of work while serving to dissolve frictions of difference among people who might otherwise not interact in an increasingly segregated world.

Mediated crowdsourced project work is germane for two main reasons. First, the effort and ability of firms to reach innovative freelancers disassociated from firms and even unemployed conceivably can avoid institutionalized discrimination at the outset because actors in crowdsourced activity are recruited on the basis of their expertise relative to specified problems, not their work associations, previous history, or formal education. If we accept that many people earning below a living wage have well-developed skills, even if informally developed, then this system in principle has the potential to be inclusive, although to date, inclusivity has not been a goal and indeed has not been served. Second, the immateriality of collaboration in knowledge networks associated with project work (as opposed to selling intellectual property) brings people into contact with one another on the basis of their expertise. If innovative communities of practice Footnote 11 that are tapped for expertise were to open to diverse actors, then people who might otherwise not interact beyond superficial exchanges could gain trust and mutual respect through working together in meaningful interaction aimed at effective problem solving.

The idea of people developing mutual respect and trust in the process of using complementary expertise to solve problems for firms suggests that people learn about each other and develop social knowledges in the process of work with economic, material objectives. This is key, although the content of social knowledges typically is absent from analysis of economic networks in light of the conventional instrumentality of the social for the economic.

I suggest extending types of knowledges in economic-oriented literatures to include social knowledges, which I define as the generation of knowledges about actors’ lives and circumstances, talents, idiosyncrasies, tragedies, and humor. Existing typologies of economic knowledges are rooted in Karl Polanyi’s (1958, 1966) distinction between tacit and coded knowledges. Frank Blackler’s (1995) elaborated typology includes embrained knowledge (rooted in an individual’s cognitive abilities); embodied knowledge (practical knowledge developed in specific physical contexts, as in project work); encultured knowledge (rooted in shared understanding developed through socialization); embedded knowledge (subjective knowledge embedded in a context), and encoded knowledge (knowledge that can be presented in manuals, books, websites, and the like). The addition of social knowledges to existing typologies rests on the recognition of problems of social interaction. In an inclusive framework, exclusions wrought of segregation require attention.

Problematizing the Social: Conceptualizing Exclusion in Relation to Social Knowledges

Constructing networks among people who might otherwise not interact due to membership in different affinity groups (by class, race, ethnicity, gender, and the like) is fraught with problems in light of people’s life experience in a hyper-segregated world. Although segregation commonly is viewed in the context of residential areas and school districts, occupational segregation also is well documented. Further, the management literature has documented frictions of difference within occupations in both material and virtual workplaces, as well as tendencies for people to want to work with people similar to themselves (e.g., Brown, Jenkins, & Thatcher, 2012; Joshi, 2006). Electronic workplaces in association with e-collaboration have been shown to embed implicit sociolinguistic biases regarding gender (Gefen, Geri, & Paravastu, 2007); moreover, different modes of e-communication have been shown to foster or inhibit constructive social relations in the context of diverse participants (Brown et al., 2012). Difference matters, consistent with geographer Mark Graham’s (2011a) more general point that virtual space embeds biases relative to the range of axes of difference that exist in material space, while also creating new axes of difference. Recognizing persistent problems of difference departs from various sanguine views, such as the notion that activity in virtual space portends a more democratic future (e.g., see critical reviews by Graham, 2011b; Etling, Faris, & Palfrey, 2010), or that convivial interaction among diverse groups signifies the dissolution of frictions of difference, despite the superficiality of interaction (Gilroy, 2004, 2005).

Segregation along any of many or a combination of axes of difference contributes to the increasingly polarized nature of our world because it blocks access to information and opportunity to groups that lack resources, and moreover, it renders those without access out-of-sight and out-of mind (Young, 2000). Drawing from the theory of communicative action (Habermas, 1984), we can understand segregation in terms of the absence of communication among different groups via the construction of invisible and sometimes visible walls among groups, which then generate misinformation and the production of homogenizing and typically derogatory stereotypes. Misinformation in turn produces fear and discriminatory practices, which reinforce segregationist tendencies.

If segregation is understood as the socio-spatial production of ignorance, whether on the ground or virtually, then the task is to dissolve ignorance by developing new social knowledges through meaningful interaction (Ettlinger, 2009). I pursue new types of knowledge networks as a possible context for social change in association with the emergence of open innovation. The recognition of social knowledges in typologies of knowledge suggests important implications for adapting theory of knowledge generation regarding competitiveness to the domain of social relations while recognizing the benefits for economic performance. In light of the relative absence of attention to problems of knowledge generation in the realm in social theory, I turn now to literature on economic networks for clues regarding knowledge generation and sharing, with the aim of using these insights toward social knowledges in the context of economic dynamics.

Adapting Theories of (Economic) Knowledge Networks to Social Relations: Generating and Sharing Knowledges, and the Nagging Problem of Trust and Familiarity

Research in economic geography and sociology and allied fields in business and management has grappled with the “soft” issue of trust as a linchpin in the generation of knowledges for innovative activity among firms. Despite an absence of interest in the content of social knowledges and their usefulness for social issues, this literature nonetheless is germane because it clarifies the complexity of establishing trust and mutual respect, irrespective of the agenda.

Economic geographers in particular have engaged the spatiality of trust. The idea emanating from economic sociology that economic action is socially embedded (Granovetter, 1985) became axiomatic in economic geography, which initially meshed social with local embeddedness (Hess, 2004). However, the idea that feelings of trust associated with knowledge generation and exchange necessarily require the familiarity of physical, face-to-face interaction (e.g., Gertler, 2003; Morgan, 2004; Scott & Storper, 2003) eventually became upended in topological renditions of networks conceptualized in non-Euclidean space (e.g., Adams, 1998; Allen, 2009; Amin & Cohendet, 2004).Footnote 12 Unbounding learning regions opened analysis to networks and collaboration spread across space (Amin, 2004; Goodwin, 2013) and the recognition of multiple types of proximities—physical, organizational, cultural, social, institutional, virtual—each with their own configurations of constraints and opportunities (Amin & Roberts, 2008; Bathelt, Feldman, & Kogler, 2011; Boschma, 2005; Jones & Search, 2009). Critiques of earlier notions of cozy, localized networks recognized that such networks may not result in innovativeness, as previously thought (Gordon & McCann, 2005), or they often are ineffective (Ettlinger, 2008; Hadjimichalis & Hudson, 2006). Moreover, localized networks became problematized in terms of negative tendencies toward “spatial myopia” (Maskell & Malmberg, 2007) or “ lock-in” and innovative stagnation (Boschma, 2005). In contrast, global relations based on strategic bridging of knowledges across different networks suggested productive and creative possibilities (e.g., Bathelt, Malmberg, & Maskell, 2004).

However, the implications for knowledge generation have become complex and contingent. Far from a “flat world” of knowledge generation as a result of a wider range of opportunities across space (Friedman, 2005), there are concerns about what kinds of knowledge transfers are possible across space, in part due to the problem of trust among actors who lack familiarity with one another. Whether using Karl Polanyi’s (1958, 1966) simple dichotomy of coded and tacit knowledge or more elaborated versions, there seems to be a consensus that a certain type of knowledge, relational knowledge, labeled “tacit” knowledge in Polanyi’s conceptualization or encultured and embedded knowledges in Blackler’s (1995) scheme, is less open to activity spread across space (e.g., Bathelt et al., 2004; Faulconbridge, 2006; Jones, 2007). People are reluctant to share their knowledges without having established familiarity (Han & Hovav, 2013). This may seem like a déjà vu—that research on networks and knowledge exchange is back to the original problem of necessitating face-to-face interaction, thereby limiting opportunities across space. Yet the situation is more complex, for several reasons.

First, from an epistemological vantage point, the process by which researchers of different camps have interpreted trust and familiarity relative to space differs. Topographically oriented research that assumes the dependence of trust formation on face-to-face contact emanates from analysis that begins with a particular spatial configuration of economic activity. In contrast, topologically oriented research, which has focused on communities of practice across space, directs attention not to what knowledge is generated by a particular spatial configuration of activity, but rather, what practices in the everyday economy do or do not require face-to-face interaction (Amin & Roberts, 2008; Faulconbridge, & Hall, 2009; Jones, 2008); analytically researchers start with, rather than infer, processes, and thereby can avoid spurious conclusions about processes of interaction based on patterns of activity. Moreover, this latter approach permits sensitivity to variation in conditions for sharing and exchanging knowledges relative to different industry contexts (Brenner, Cantner, & Graf, 2013; Tether, Li, & Mina, 2012).

Second, substantively, the spatiality of networks changes over time (Gückler, 2007). Spatially proximate ties made at one point in the evolution of a network can anchor relations as members of a network change location over time, and new ties can be developed while older ties dissolve. Moreover, the dynamics of any one network change as ties develop and evolve among actors in different networks.

Third, and relatedly, interdisciplinary research has suggested that with all the sophistication of ICTs, face-to-face communication remains the richest, especially for complex situations (e.g., Glückler & Schrott, 2007; Kock & Nosek, 2005). Interestingly, the competitive practice of bridging relations between actors in different networks has been shown to depend on bonding relations within networks (Kraut, Steinfeield, Chan, Butler, & Hoag, 1999; Han & Hovav, 2013). Accordingly, management techniques such as brainstorming and focus groups have been recommended at the outset of a project to cultivate bonding and anchor effective social relations that can evolve outside conditions of initial spatial proximity (Han & Hovav, 2013). Actually, the nature of the “location” of actors itself is fluid, if we consider cases of temporary spatial proximity owing to the mobility of many professionals (Almeida & Kogut, 1999; Torre & Rallet, 2005; Williams, 2006), and possibilities for the construction of temporary spatial clusters of innovation (e.g., Maskell, Bathelt, & Malmberg, 2006).

Finally, certain types of ICTs such as teleconferencing permit face-to-face relations across space, thereby creating virtual localization, overcoming the constraint of physical distance. However, research has shown that increased e-networking depends on effective and constructive personal relations within networks (Kraut et al., 1999), or at least in particular culture-specific contexts (Burt et al., 2000). These findings corroborate more general findings that effective bridging between networks of any kind (material or virtual) is contingent upon internal relations. Knowledge is subjective, and thus personal experience and relational capital (Kale, Singh, & Perlmutter, 2000) are pivotal resources at the outset of any project (Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka & Konno, 1998). Unsurprisingly, then, research on suites of ICTs for e-collaboration has suggested that asynchronous communication (e.g., discussion boards, e-mail, blogs, audio or video streaming, databases, or document libraries) are more appropriate at a later stage in a project, after actors’ relations become anchored in early synchronous communication (e.g., through video, and audio conferencing, electronic chatting, or instant messaging) (Han & Hovav, 2013). This technosocial framework is consistent with research that advocates beginning project work with focus groups and brainstorming sessions, focusing on other types of communication later in the evolution of a project (Kraut et al., 1999).

It seems, then, that relational knowledge does not necessarily require face-to-face interaction, and further, localization can be achieved virtually across space with appropriate ICTs, as well as physically in short-run clustering of people from different places (Bathelt & Turi, 2011).

But here is the rub: Just as in problems of de-segregation in housing and school districts, co-location of project participants, whether virtual, physical, or temporary, does not necessarily produce trust.Footnote 13 A simple, basic, practical point complicates matters, namely, what people think of each other a priori, and the nature of power relations , affect prospects for knowledge sharing (Brown, Jenkins, & Thatcher, 2012). Moreover, research has shown that knowledges are communicated in verbal and nonverbal ways, including body language and other contextual cues (e.g., Harvey, Novicevic, & Grarrison, 2004), potentially inhibiting productive interaction in physical or virtual face-to-face settings (Brown et al., 2012; Shachaf, 2007). Bias is embodied, reinforcing the importance of incorporating faces as well as bodies in research on networks. Critical human geographers writing about issues in field strategies have highlighted some of the problems of, for example, focus groups, wherein power relations can surface and thereby produce silences among some members (Hyams, 2004). Similarly, in the business world, brainstorming sessions can inhibit creativity as different participants take on more and less responsibility in a groupthink culture (Cain, 2012). Sometimes network analyses incorporate power relations (e.g., Faulconbridge & Hall, 2009) regarding, for example, selective recruitment by gatekeepers and executive search firms (Faulconbridge, Beaverstock, Hall, & Hewitson, 2009), agents’ relational positioning (Weller, 2009), different kinds of proximities (Jones & Search, 2009), and uneven access to circuits of knowledge (Faulconbridge, 2007; Grabher, 2002).Footnote 14 And sometimes research in economic geography on networks connects with gender issues (Blake & Hanson, 2005; Hanson & Blake, 2009; McDowell, 2000). However, there is relative silence on issues of race and ethnicity and, more generally, issues of difference broadly construed.Footnote 15 The “soft” field of feelings and interpersonal relations remain central yet relatively unexplored.Footnote 16

The Difference that Difference Makes

Injecting problems of difference (along any of many axes) into the problematic arena of knowledge generation and sharing deepens already existing challenges. Thinking about difference entails more than adding Others to existing groups of workers; rather, it requires altering strategies that might otherwise be developed. For example, whereas there seems to be a consensus from e-collaboration and general management and organization studies that techniques for social bonding and building social awareness should be developed at the start of a project, whether in virtual or physical face-to-face settings (Han & Hovav, 2013; Kraut et al., 1999), difference might be served best differently. Research on heterogeneous groups recognizes that although diversity is seen instrumentally as productive due to a multiplicity of knowledges and perspectives (Shachaf, 2007), people nonetheless prefer to work and interact with those most similar to themselves, and moreover, are reluctant to share their knowledges with Others (Brown et al., 2012) in the context of prevailing preconceived views and derogatory stereotypes (Brown et al., 2012; Giambatista & Bhappu, 2010). Admittedly, economic performance can be served while social identities and relations are not, but, beyond ethics, economic productivity at the expense of the social arguably is sub-optimal because constructive social relations are strategic for economic performance.

Interestingly, research specifically on collaboration when difference is considered suggests a trajectory of communication strategies in which the outset of a project might benefit from asynchronous modes of communication or possibly avatars (Kock & Nosek, 2005, p. 3), and subsequently move to face-to-face interaction, virtually or physically, followed by diverse modes of communication depending on project needs (Brown et al., 2012). Asynchronous modes of communication, which lack physical cues, conceal at least some elements of difference,Footnote 17 permitting more focus at the outset on the objective content of interaction (Brown et al., 2012; Giambatista & Bhappu, 2010; Shachaf, 2007),Footnote 18 and possibly facilitate a formulation of identities at least partially unencumbered from visual cues among diverse actors at the start of new project (Amiri, Gholipour, & Sohrabi, 2011). A trajectory of asynchronous and synchronous communication is best conceptualized as dialectical rather than unilinear to permit adaptation to unanticipated dynamics (Brown et al., 2012). The difference that difference makes in the strategic design of project communications would seem to occur notably at the outset, entailing a reversal of the conventional logic for the appropriate communication platform at this stage.

But if the ultimate aim targets social relations in the course of project work, there remains more to consider. If a principal task is to develop social knowledges, beyond sharing economic knowledges in collaborative project work, then at least a portion of overall collaboration should entail some physical face-to-face interaction through work as well as social time. Personal relations matter in the sharing of knowledge s, or more generally, private resources (Hambley, Kline, & O’Neil, 2007; Kraut et al., 1999; Uzzi, 1999). Further, the creation of a space and time for people to learn about each other in the course of collaborating on a project is complex because social learning is far from automatic. Rather, it requires careful planning of the mundane—seating arrangements, for example—to avoid the self-segregation during social time that has been documented in apparently “mixed” residential complexes and lunchrooms in schools.Footnote 19

The idea here is to take what we know about the value of routinized rhythms of interaction from communities of economic practice in innovative activity (Brown & Duguid, 1991), and introduce such routinization in new social relations formed around collaborative project work.Footnote 20 Drawing from what we know about path dependence and the value of respect for another’s work for future interaction, the sharing of knowledges about people as well as project work positions future social relations constructively. Pragmatically, the agenda produces logistical problems as well as the expense of ensuring participants’ travel to a central place for the portion of project work requiring physical face-to-face interaction (see Feller, Finnegan, Hayes, & O’Reilly, 2012, regarding the critical role of stability for open innovation). In this regard, public-private partnerships may be crucial to provide continual support.

Envisioning Socially Responsive, Collaborative Knowledge Networks in the New Economy

The short-term nature of collaboration and the continual reconfiguration of proactively constructed networks ensure a continual meeting ground of diverse actors. The main drawback of network ephemerality from the vantage point of solvers is the potential instability of work.Footnote 21 Especially in light of one of the objectives to serve diverse labor markets in the context of increasing socioeconomic polarization, the type of system I advocate is one that should have the support of local and federal governments and other public and private organizations to sustain continual employment through a web of solver networks.

There is an existing model for such support , although the solvers in this model are firms (not individual people) and the goal is economic, not social. The previously mentioned Agile Web was formed and operated under the auspices of the state-funded Ben Franklin Technology Partners at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania. The center works with federal, state, and regional agencies, universities, and the private sector in a mission to achieve technology-based economic development. Prior to the formation of the Agile Web, the National Science Foundation funded an “Agility Forum” at Lehigh University, which laid a foundation for the development of the Web. The funded conceptualization and planning of the Agile Web occurred over a period of 2 years.

Consider the possibilities if federal, state, and regional agencies, universities, and the private sector were to reconfigure goals so as to value the social in the course of achieving economic ends. There are precedents for such reconfiguration, although not specifically in the context of open innovation and related network strategies (Gibson-Graham & Cameron, 2010; Gibson-Graham, Cameron, & Healy, 2013). One is the Mondragón Cooperative Corporation (MCC), which was founded in 1956 in Spain’s Basque region with funding by business owners, institutions, workers, and municipal government. The MCC persists through the present as a business group based on democratic governance and a privileging of social and community objectives. Although it developed as a regional industrial complex spanning manufacturing, finance, distribution, housing, services, research, education, and training, it now has operations worldwide. Another model was Tony’s Blair’s “Third Way” programs in the United Kingdom in which the U.K. government provided financial and bureaucratic support for the development of “social enterprises ” defined with reference to social and community objectives. In Australia, the Victoria government allocated 9.2 million dollars to a community enterprise strategy, and with the Brotherhood of St. Laurence supports 42 localities in the development of community enterprises. This selection of exemplars in different contexts demonstrates the plausibility of government and various local institutions and actors taking a proactive and supportive role in the systematic development of enterprises oriented to social and community goals. J. K. Gibson-Graham and Jenny Cameron (2010) have indicated that some social enterprises are remunerative and some are not; some “fail” yet serve an important role in providing a platform for the participants to move on to other enterprises, and in that sense, can reasonably be understood more as successes than failures.

My concern here is for remunerative and continual employment in mediated crowdsourced project work in the context of open innovation and related knowledge networks. The imperative for the provision of continuous, living-wage work across ephemeral networks derives from a fundamental concern for problems of under-consumption among increasingly large numbers of people worldwide, as well as the ills of the credit economy, in turn related to insufficient or no wages (Lazzarato, 2011/2012). The agenda to construct collaborative networks of people, not firms, connects with an innovation of open networks associated with open innovation: crowdsourcing. Although crowdsourcing often is exploitative (Howe, 2008; Korkki, 2014), I suggest treating it as a tool to achieve social objectives by creating a time and space for diverse people to realize their talents while being paid a living wage, and in the process develop meaningful knowledges about each other using multiple modes of communication in the course of sharing economic knowledges in temporary, collaborative networks that respond to customized demand for expertise in the context of open innovation.

Municipal governments might well consider it desirable to develop localized networks that are inclusive to avoid local socioeconomic and political tensions wrought of exclusionary processes. The multidimensionality of the agenda developed in this chapter suggests that it may be prudent to spatially fix it initially at the local scale to permit localized field research for the identification and establishment of knowledge networks in connection with the intricate dynamics of classifying problems relative to requisite sets of expertise. This sort of project need not, however, remain spatially bounded. Considering the long-run possibility of such projects worldwide, local mediators (supported by government at different scales) could work to ensure continual employment via local projects while connecting with other projects in other places; the local versus extra-local issue can, but need not, be a zero-sum game with appropriate goals, planning, and local participation. The evolution of the Mondragon Cooperative Corporation from localized to globally extensive is a case in point, although as J. K. Gibson-Graham (2006, p. 123) has pointed out, it is unclear whether democratic practices and the privileging of social objectives extend to offshore operations. Indeed, a transfer of social relations across space is anything but perfunctory and hardly a seamless operation; for this reason, beginning mediated crowdsourced project work at the metropolitan scale is pragmatic.

One central problem is recruitment. Recall Cisco’s open electronic call for expertise and the considerable response across the world—2500 inventors across 104 countries. While many of those responding may well be without stable employment despite their skills, they nonetheless are “plugged in” to a global network, even if exploitative. In addition to all those who did not win Cisco’s one-time prize, consider also the large numbers of people who remain unplugged from opportunities—as previously explained, a defining feature of segregation. People in untapped labor markets live in resource-poor areas that lack access to lucrative information, in part due to the absence of material and immaterial resources as well as institutionalized discrimination.

Extending knowledge networks to untapped labor markets, including people who are talented but lack formal work and educational experience, requires field research as a crucial complement to electronic communication to engage the complex terrain of sedimented exclusions.Footnote 22 Placing appropriate computer hardware and software in such communities at central-access locations would be ineffective without also seeking out and connecting with local gatekeepers as well as would-be gatekeepers across multiple community groups engaged in a wide range of activities.Footnote 23 While incorporating new members into a community of practice requires significant effort (de Vreede et al., 2007), the challenges are multiplied when new members come from previously excluded communities. The role of mediators entails coordinating, connecting, facilitating, and indeed empowering (Obstfeld, 2005).Footnote 24

To avoid the pitfalls of top-down programs, it would be especially helpful if leaders of field research were recruited from within excluded neighborhoods (Kindon, Pain, & Kesby, 2007). An important part of the field research in these contexts entails assisting people who have been undervalued and might otherwise self-select out of opportunities to recognize and draw upon their strengths. Jenny Cameron and Katherine Gibson (2004) carried out precisely this type of field work in Australia, where they sought out people in communities devastated by industrial restructuring; crucially, these researchers recognized that the devastation was as much subjective as a matter of objectified conditions. Using field strategies such as focus groups, they helped people develop new subjectivities, based on recognition of their skills and talents despite exclusion from the market. In mediated crowdsourced project work, field research also must entail a constructive way to screen and evaluate expertise that would have to depart from existing techniques such as competitions (Howe, 2008; Lampel, Jha, & Bhalla, 2012; Villarroel, Taylor, & Tucci, 2013), which are win-lose propositions and incompatible with the objectives I have laid out. Face-to-face focus groups may be at least one viable alternative (Schweitzer, Buchinger, Gassmann, & Obrist, 2012). Admittedly, the task is huge, encompassing field research , continual classification of seeker problems in connection with appropriate solvers (Feller et al., 2012), and effective communication among all actors orchestrating the different components of the project.

The dynamics of the mediated crowdsourced project work I envision entail something akin to the Agile Web, except that the solvers are talented people, not firms, who are identified at the outset and continually across a metropolitan region. In an era of increasingly customized demand, wide-ranging problems (from mechanical to electronic) that emerge are crowdsourced. In the scenario laid out in this chapter, crowdsourcing targets networks of diverse solvers (people) who would earn a living wage by collaborating in problem solving and the development of innovations demanded by seekers (private as well as public, organizations). Networks, coordinated by mediators between seekers and solvers, form around particular problems, dissolve, and form again with different membership relative to the expertise required for new problems. As networks form and reconfigure relative to the constitution of membership, each solver interacts with an increasingly wide array of people while developing social knowledges in the course of each collaboration. The point is to construct social knowledges to erode ignorance in the course of fluid, living-wage, collaborative work, supported by public and private institutions that serves both the economy and its people. The process renders economic space social and vice versa.

Conclusion: A Matter of Values

The agenda of this chapter is to conceptualize how to work towards social ends by recognizing and acting on the role of meaningful social knowledges in the pursuit of knowledges for economic gain. The context is the emergence of new production dynamics and labor recruitment strategies amid dramatically increasing socioeconomic polarization and exclusion. To date, crowdsourcing associated with open innovation has proven to be lucrative for firms but also highly exploitative and exclusive. Recognizing insidious dimensions of the market, the underlying suggestion here is to make use of the market, not to work against it, with public and private support for social as well as economic objectives. If the social and the economic as well as the cultural and political are mutually constituted, then it is sensible to refuse the conventional privileging of one dimension, the economic, at the expense of another, commonly the social. I have privileged social over economic goals to encompass strategies that might otherwise be jettisoned, but economic goals remain nested in the broader project. At this critical juncture in the global economy, the agenda I have in mind entails nothing less than reconfiguring the values that govern our lives.

Notes

- 1.

Alternatively, Bourdieu’s (1986) discussion of social capital casts individuals’ membership in a network as benefitting individuals, notably regarding their social positioning. This view does not negate the instrumental view of people relative to economic networks, but it offers more in terms of potential benefits of social capital. This said, the concern of this chapter is less with the benefits of network relations to an individual and more with a specifically relational view of social interaction, that is, the development of constructive relations among individuals based on the development of trust, mutual respect, and the like.

- 2.

Achieving economic goals at the expense of social goals can be a matter of exploiting vulnerable workers for the sake of personal or shareholder gain. Other processes include myopic strategic planning (Ettlinger, 2008) as well as implicit biases against, and thus exclusion of, talented people who may be outside entrenched power networks (Ettlinger, 2003; Faulconbridge, 2007; Faulconbridge and Hall, 2009).

- 3.

Foucault conceptualized systems of governance in terms of the conduct of conduct (e.g., Foucault, 2004/2007), with reference to the strategies, tactics, and programs that guide actors to make choices (often unconsciously) in accordance with societal norms. Counter-conduct, then, is the governance of practices that counter those norms (e.g., Foucault, 2004/2007, p. 201).

- 4.

Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk subsidiary (Mechanicalturk.com) exemplifies non-routine but menial work. Skilled labor is required, but for relatively low-skilled tasks that nonetheless are non-routine and therefore unamenable to operation by artificial intelligence. Amazon.com lists jobs or human intelligence tasks (HITs) for other companies that pay Amazon.com 10 % of the fee for completed tasks. People are paid extremely low wages by the task, not the unit of time—a situation that has been likened to “piece work” in a digital sweatshop.

- 5.

For a survey in 2013 of the top 50 Forbes Global 2000 firms with CVC programs, see Battistini, Hacklin, and Baschera (2013).

- 6.

Intel’s activity in the 1990s serves as an instructive example of interlinked activity among firms and novel strategies to coordinate innovativeness (see discussion in Gawer & Cusumano, 2002). By the late 1980s the pace of Intel’s innovation in its core product, computer microprocessors, exceeded the pace of innovation in IBM’s personal computer (PC) architecture. In response, Intel staffed a new lab with software engineers to find new uses for its hardware (microprocessors), in turn to stimulate demand for a new generation of personal computers that require Intel’s core product. Its strategy in the next decade and into the twenty-first century has been “to establish the technologies, standards and products necessary to grow demand for the extended PC through the creation of new computing experiences” (cited in Gawer & Cusumano, 2002, p. 25).

- 7.

The concept of agility was first developed in U.S. defense-related production and eventually became wedded with the concept of the virtual enterprise in the early 1990s (Goldman et al., 1995; Goranson, 1999). The Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) and the Pentagon created a program managed by several military services (especially the Air Force) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) to develop an organizational strategy to respond to unexpected problems in a post-Cold War environment; the research firm Sirius-Beta developed a key role in the program, connecting the idea of effectively and rapidly tapping external resources (agility) with the idea of ephemeral networks (the virtual enterprise). The NSF supported research centers at universities, pilot production programs, and information networks regarding the new paradigm. In 1991 the NSF supported a workshop at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania. Political support and thus defense dollars eventually diminished, although the NSF continued its support for programs, conferences, workshops, and publications to disseminate the new paradigm to the private sector.

- 8.

Around 90 % of Proctor and Gamble’s patents in 2002 were never commercialized as innovations—a situation that is emblematic of tendencies to warehouse inventions (Chesbrough, 2006a, p. 9). In the context of open innovation, dormant inventions take on new value as a means to earn revenue quickly as other firms look to license in new technologies to avoid the costs of technology development.

- 9.

These third-party organizers conventionally are termed “intermediaries.” Taking a cue from Bruno Latour’s (2005) compelling argument that “intermediary” implies neutrality, I use the term “mediator.”

- 10.

Feller et al.’s (2009) classification of mediators includes the following exemplars: Innocentive, founded in 2001; NineSigma, founded in 2000; Yet2, founded in 1999; YourEncore, founded in 2003; and InnoCrowding, founded in 2006. Companies specializing in connecting freelancers in software development, website design, customer service, and translation in low-wage countries with businesses (including SMEs) in high-wage countries include: oDesk, launched in 2005; Freelancer, launched in 2009; and Guru, launched as eMoonlighter in 1998 (Korkki, 2014).

- 11.

The term “communities of practice,” CoPs (Amin & Cohendet, 2004; Amin & Roberts, 2008; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998; Wenger, McDermott, & Snyder, 2002), refers to context-specific practices that foster innovativeness among entrepreneurs through collaboration. An independent but parallel concept is “ba,” which translates from Japanese as “place,” in reference to public arenas in which innovative knowledges are generated and exchanged (Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka & Konno, 1998). Both concepts emerged with a localized context in mind, but evolved to consider collaborative practices across space.

- 12.

The sense of space from a Euclidean and topographic perspective represents the relation between two points in space as a straight line; space is understood as a container, constituted by locations that can be mapped as Cartesian coordinates. A non-Euclidean and topological sense of space recognizes that in practice the relation between two points in space may be non-linear due to physical, social, cultural, political, and economic barriers; space is folded. The non-Euclidean, topological perspective recognizes that relations between people across space may be stronger than relations between people at the same location, countering longstanding assumptions about the positive correlation between physical and social distance. Doreen Massey’s (1993, 2005) “progressive sense of place” understands places as points of articulation between processes in local contexts and the wide-ranging experiences of people in places who have traversed many contexts; accordingly, places are characterized by diverse and not necessarily harmonious realities and identities. See also John Allen’s (2003, 2009) scholarship on topologies of power.

- 13.

Approaching segregation relative to predefined, bounded residential areas, school districts, or workplaces is problematic because the problem is identified in terms of location, without regard for processes of inclusion and exclusion. The locational conceptualization of segregation underscores the conventional de-segregation strategy that locates diverse people in the same physical or virtual place. This locational strategy ironically is repeated over time and across space, despite documentation of persistent segregation within apparently integrated areal units such as school districts (Riley & Ettlinger, 2011) and neighborhoods (Joseph, Chaskin, & Webber, 2007). Given that the usual goal is defined not in terms of the nature of interaction, but rather in terms of the pattern of co-location, success is relatively easily achieved, perhaps in part explaining views that segregation is not really a problem. In contrast, a topological and non-Euclidean (as opposed to topographic and Euclidean) approach to segregation recognizes that segregation ripples through everyday life at fine scales, within so-called mixed residential communities such as schools, as well as in workplaces, including virtual workplaces.

- 14.

See Christopherson and Clark (2007) for a discussion of power relations in firm networks in which the actors are represented at the scale of firms.

- 15.

For example, Ash Amin, who has written extensively on issues in economic geography on knowledge generation (Amin, 2004; Amin & Cohendet, 2004; Amin & Roberts, 2008), has published on issues of race (e.g., Amin, 2010) and more general social theory (Amin & Thrift, 2013), but this part of his scholarship tends to be discrete from his publications on issues in economic geography. Similarly, Doreen Massey, whose early scholarship (Massey, 1984) paved the way for analysis of spatial divisions of labor, eventually departed from issues of firms and the economy (e.g., Massey, 1991, 2005).

- 16.

The allusion to emotions here differs from ideas about “emotional intelligence” in the business and management literature, which engages emotions in the context of fixed hierarchical structures and focuses on particular actors who are leaders to manage the emotions of their staffs—a top-down approach that implicitly is about policing emotions to fit with a prescribed configuration of emotion and reason to accommodate firm goals of productivity. The perspective here differs insofar as first, the usual instrumentality of the social for the economic is reversed, and second, emotions are not to be managed or possibly suppressed, but rather understood so as to enable constructive relations (Ettlinger, 2004).

- 17.

Emoticoms, grammar, and the like are not, however, hidden in asynchronous communication (Brown et al., 2012).

- 18.

- 19.

Lee’s (2007) provocative account of a neighborhood’s effort to deter Vancouver planners, engineers, politicians, and developers from moving ahead with plans for demolition and gentrification is instructive. Organizers of the movement against demolition and gentrification recognized that the actors behind these plans regarded the neighborhood as blight, and did not have any idea or even image of the people living in the neighborhood. Rather than protest, community leaders invited city officials and representatives of the new planning movement to their neighborhood for festivals, dinner, and walking tours, paying close attention to mundane details such as seating arrangements at dinner and the like. The face-to-face interaction and development of personal relations culminated in the termination of city plans for demolition and gentrification following what might be described as a concert of orchestrated “situated practices” that emplaced actual faces and livelihoods in the image of the neighborhood.

- 20.

- 21.

There also is a drawback of ephemeral networks from the vantage point of economic activity and goals, namely that the complex problem of establishing trust must be continually engaged—a problem that closed networks need not engage. As previously indicated, however, closed networks have other problems, and further, changing conditions have required increasing openness. The task then, is how to engage the new realities constructively, creatively, and effectively.

- 22.

Although formal education often is used as a proxy measure for skill, this measure misses the variety of avenues by which people develop skills and knowledges. This much has been recognized by the business world, which has recognized that many educational systems around the world lack appropriate training for many workplaces. In response, training increasingly is linked to continuous learning in ongoing on-the-job training (Marković, 2008). Accordingly, many firms develop rigorous recruitment and selection criteria based on apparent intelligence, sense of responsibility, ambition, and the like and subsequently train workers themselves rather than rely on educational institutions.

- 23.

I include legal as well as illegal activity here. Regarding the latter, the view here is that illegal activity is most fruitfully engaged by providing new opportunities and practices, not by imprisoning and more generally constraining people who have been subjected to institutionalize discrimination—a system that has been shown to multiply existing problems. The view overall is consistent with Foucault’s point that arriving at new truths requires the development of new practices, as opposed to proselytizing (1980, p. 133) or repression, which produces rather than eliminates actions on a targeted population (Foucault, 1976/1990).

- 24.

References

Adams, P. (1998). Network topologies and virtual place. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 88, 88–106. doi:10.1111/1467-8306.00086

Allen, J. (2003). Lost geographies of power. Malden: Blackwell.

Allen, J. (2009). Powerful geographies: Spatial shifts in the architecture of globalization. In S. R. Clegg, & M. Haugaard (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of power (pp. 157–174). London: Sage.

Almeida, P., & Kogut, B. (1999). Localization of knowledge and the mobility of engineers in regional networks. Management Science, 45, 905–917. doi:10.1287/mnsc.45.7.905

Amin, A. (2004). Regions unbound: Towards a new politics of place. Geografiska Annaler, 86, 33–44. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00152.x

Amin, A. (2010). The remainders of race. Theory, Culture & Society, 27(1), 1–23. doi:10.1177/0263276409350361

Amin, A., & Cohendet, P. (2004). Architectures of knowledge: Firms, capabilities, and communities. New York: Oxford University Press.

Amin, A., & Roberts, J. (2008). Knowing in action: Beyond communities of practice. Research Policy, 37, 353–369. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2007.11.003

Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (2013). Arts of the political: New openings for the left. Durham: Duke University Press.

Amiri, B., Gholipour, A., & Sohrabi, B. (2011). The influence of information technology on organization behavior: Study of identity challenges in virtual teams. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 7(2), 19–34. doi:10.4018/jec.2011040102

Bathelt, H., Feldman, M. P., & Kogler, D. F. (Eds.). (2011). Beyond territory: Dynamic geographies of knowledge creation, diffusion and innovation. New York: Routledge.

Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., & Maskell, P. (2004). Clusters and knowledge: Local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Progress in Human Geography, 28, 31–56. doi:10.1191/0309132504ph469oa

Bathelt, H., & Turi, P. (2011). Local, global and virtual buzz: The importance of face-to-face contact in economic interaction and possibilities to go beyond. Geoforum, 42, 520–529. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.04.007

Battistini, B., Hacklin, F., & Baschera, P. (2013). The state of corporate venturing: Inside of a global study. Research-Technology Management, 56(1), 31–39. doi:10.5437/08956308X5601077

Beck, U. (2000). The brave new world of work (P. Camiller, Trans.). Malden: Polity Press. (Original work published 1999)

Blackler, F. (1995). Knowledge, knowledge work and organizations: An overview and interpretation. Organization Studies, 16, 1021–1046. doi:10.1177/017084069501600605

Blake, M. K., & Hanson, S. (2005). Rethinking innovation: Context and gender. Environment and Planning A, 37, 681–701. doi:10.1068/a3710

Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39, 61–74. doi:10.1080/0034340052000320887

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood.

Brenner, T., Cantner, U., & Graf, H. (Eds.). (2013). Introduction: Structure and dynamics of innovation networks. Regional Studies, 47, 647–650. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.770302

Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organizational Science, 2, 40–57. doi:10.1287/orsc.2.1.40

Brown, S., Jenkins, J. L., & Thatcher, S. M. B. (2012). E-Collaboration media use and diversity perceptions: An evolutionary perspective of virtual organizations. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 8(2), 28–46.

Burt, R. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burt, R. (2005). Brokerage and closure: An introduction to social capital. New York: Oxford University Press.

Burt, R., Hogarth, E., & Michaud, C. (2000). The social capital of French and American managers. Organization Science, 11, 123–147. doi:10.1287/orsc.11.2.123.12506

Cain, S. (2012, January 13). The rise of the new groupthink. New York Times, Retrieved from http://nyti.ms/1wUaLCc

Cameron, J., & Gibson, K. (2004). Participatory action research in a poststructuralist vein. Geoforum, 36, 315–331. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2004.06.006

Chesbrough, H. (2006a). Open business models: How to thrive in the new innovation landscape. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Chesbrough, H. (2006b). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Chesbrough, H., & Brunswicker, S. (2013). Managing open innovation in large firms: Survey report, executive survey on open innovation. Berkeley: Fraunhofer.

Chesbrough, H.,Vanhaverbeke, W., & West, J. (Eds.). (2006). Open innovation: Researching a new paradigm. New York: Oxford University Press.

Christopherson, S., & Clark, J. (2007). Power in firm networks: What it means for regional innovation systems. Regional Studies, 41, 1223–1236. doi:10.1080/00343400701543330

Coase, R. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4, 386–405. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x

Cooke, P., De Laurentis, C., MacNeill, S., & Collinge, C. (Eds.). (2010). Platforms of innovation: Dynamics of new industrial knowledge flows. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

de Vreede, G.-V., Tarmizi, H., & Zigurs, I. (2007). Leadership challenges in communities of practice: Supporting facilitators via design and technology. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 3(1), 1–18. doi:10.4018/jec.2007010102

Etling, B., Faris, R., & Palfrey, J. (2010). Political change in the digital age: The fragility and promise of online organizing. SAIS Review, 30(2), 37–49. Retrieved from http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4609956

Ettlinger, N. (2003). Cultural economic geography and a relational and microspace approach to trusts, rationalities, networks, and change in collaborative workplaces. Journal of Economic Geography, 3, 145–171. doi:10.1093/jeg/3.2.145

Ettlinger, N. (2004). Towards a critical theory of untidy geographies: The spatiality of emotions in consumption and production. Feminist Economics, 10(3), 21–54. doi:10.1080/1354570042000267617

Ettlinger, N. (2008). The predicament of firms in the new and old economies: A critical inquiry into traditional binaries in the study of the space-economy. Progress in Human Geography, 32, 45–69. doi:10.1177/0309132507083506

Ettlinger, N. (2009). Surmounting city silences: Knowledge creation and the design of urban democracy. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33, 217–230. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00840.x

Ettlinger, N. (2014) The openness paradigm. New Left Review, 89, 89–100.

Fabrizio, K. R. (2006). The use of university research in firm innovation. In H. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, & J. West (Eds.), Open innovation: Researching a new paradigm (pp. 134–160). New York: Oxford University Press.

Faulconbridge, J. R. (2006). Stretching tacit knowledge beyond a local fix? Global spaces of learning in advertising professional service firms. Journal of Economic Geography, 6, 517–540. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbi023

Faulconbridge, J. R. (2007). Relational networks of knowledge production in transnational law firms. Geoforum, 38, 925–940. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.12.006

Faulconbridge, J. R., Beaverstock, J. V., Hall, S., & Hewitson, A. (2009). The “war for talent”: The gatekeeper role of executive search firms in elite labour markets. Geoforum, 40, 800–808. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.02.001

Faulconbridge, J. R., & Hall, S. (Eds.). (2009). Organizational geographies of power [Special issue]. Geoforum, 40, 785–789. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.09.003

Feller, J., Finnegan, P., Hayes, J., & O’Reilly, P. (2009). Institutionalizing information asymmetry: Governance structures for open innovation. Information Technology and People, 22, 297–316. doi:10.1108/09593840911002423

Feller, J., Finnegan, P., Hayes, J., & O’Reilly, P. (2012). “Orchestrating” sustainable crowdsourcing: A characterization of solver brokerages. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 21, 216–232. doi:10.1016/j.jsis.2012.03.002

Foucault, M. (1980). Truth and power (C. Gordon, L. Marshall, J. Mepham, & K. Soper, Trans.). In C. Gordon (Ed.), Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972–1977 (pp. 109–133). New York: Pantheon.

Foucault, M. (1990). The history of sexuality: Volume 1. An introduction (R. Hurley, Trans.). New York: Vintage Books. (Original work published 1976)

Foucault, M. (1996). Sex, power and the politics of identity (L. Hochroth, & J. Johnston, Trans.). In S. Lotringer (Ed.), Foucault live: Interviews, 1961–1984 (pp. 382–390). New York: Semiotext(e) (Interview conducted by B. Gallagher, & A. Wilson, Toronto, 1982).

Foucault, M. (2007). Security, territory, population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–1978 (G. Burchell, Trans.). In M. Senellart (Ed.), New York: Palgrave. (Original work published 2004)

Foucault, M. (2008). The birth of biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979 (G. Burchell, Trans.). In M. Senellart (Ed.), New York: Palgrave Macmillan. (Original work published 2004.)

Frey, K., Lüthje, & Haag, S. (2011). Whom should firms attract to open innovation platforms? The role of diversity and motivation. Long Range Planning, 44, 397–420. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2011.09.006

Friedman, T. L. (2005). The world is flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Garrigos-Simon, F. J., Alcami, R. L., & Ribera, T. B. (2012). Social networks and web 3.0: Their impact on management and marketing of organizations. Management Decision, 50, 1880–1890. doi:10.1108/00251741211279657

Gawer, A. (Ed.). (2009). Platforms, markets and innovation. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Gawer, A., & Cusumano, M. A. (2002). Platform leadership: How Intel, Microsoft, and Cisco drive industry innovation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Gefen, D., Geri, N., & Paravastu, N. (2007). Vive la difference: The cross-culture differences within us. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 3(3), 1–16. doi:10.4018/978-1-87828-991-9.ch174

Gertler, M. (2003). Tacit knowledge and the economic geography of context, or the undefinable tacitness of being (there). Journal of Economic Geography, 3, 75–99. doi:10.1093/jeg/3.1.75

Giambatista, R. C., & Bhappu, A. D. (2010). Diversity’s harvest: Interactions of diversity sources and communication technology on creative group performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 111, 116–126. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.11.003

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2006). A postcapitalist politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.