Abstract

An important theory of international cooperation asserts that governments comply with international law because of the reputational costs incurred by reneging on public agreements. Countries that sign binding international agreements in the realm of monetary relations signal their commitment to an open economic system, which should reassure international market actors that the government is committed to sound economic policies. If the theory is correct, we should observe evidence that noncompliance is in fact costly. I test this argument by examining the effect of noncompliance with Article VIII of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement on sovereign risk ratings. The results show that noncompliance with the agreement mitigates any benefits that accrue to Article VIII signatories. The empirical evidence suggests that, in addition to improving economic and political conditions at home, governments in the developing world would improve their access to financial markets by signing and complying with international monetary agreements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

-

In addition to serving as the empirical fulcrum for the important debate on compliance between von Stein and Simmons and Hopkins, Article VIII is, as a central part of the IMF Treaty, the “first international accord in history to obligate signatories to particular standards of monetary conduct” (Simmons 2000b, 820). Countries that are signatories to Article VIII are required to maintain an open current account. Article VIII signatories are prohibited from placing restrictions on the availability of foreign exchange for goods, services, and “invisibles”—services such as legal and financial advisement, royalties, foreign remittances, etc. Sections 3 and 4 of Article VIII also proscribe states from engaging in, or permitting any of their fiscal agencies to engage in, any discriminatory currency arrangement or multiple currency practices. Although there was discussion within the IMF in the mid-1990s about adding a section to Article VIII requiring capital account convertibility, the requirement only extends to commercial credits granted by exporters or received by importers. See McKinnon (1979, 4–7).

-

In the statistical analysis, use of Fund credits—a proxy for the Fund’s sanctioning power—is unrelated to the decision to comply.

-

Italics added for emphasis.

-

The argument dovetails with Tomz’s (2007) historical analysis of sovereign borrowing. Tomz provides evidence that enforcement through coercive measures (gunboat diplomacy and trade sanctions) cannot explain historical patterns of lending and repayment; rather, governments with good reputations were charged lower interest rates by private lenders, and, preferring to maintain their good reputations, tended to honor their debts in both favorable and adverse economic circumstances.

-

I am only excluding wealthy, mature democracies in Western Europe, North America, Oceania, and Japan from the analysis. Since the early 1980s, the only significant incidences of an imposition of current account restrictions by Article VIII members in the OECD occurred in France during Mitterrand’s “U-Turn” in 1983 and in Greece in 1996–97. In addition, the focus of this article is on how compliance may or may not affect reputations, which influence access (and the terms of access) to foreign capital; OECD countries have essentially unlimited access to capital markets, so compliance with Article VIII theoretically should have little effect on the reputation of these countries. There is an additional empirical justification for limiting the sample: Blonigen and Wang (2004) present evidence suggesting that pooling of rich and poor countries is inappropriate in studies of FDI.

-

Previous work has demonstrated a strong correlation between risk ratings and interest rate spreads (Feder and Ross 1982; Mosley 2006, 98). As an admittedly crude additional test, I used Ahlquist’s (2006) data on portfolio capital inflows as a proportion of GDP to produce a bivariate correlation with my measures of creditworthiness. Unsurprisingly, I found a strongly negative correlation between portfolio inflows/GDP and IIR (ρ = −0.31, p = 0.0000) and the annual size of capital inflows and Euromoney (ρ = −0.37, p = 0.0000).

-

As discussed in Dreher and Voigt (2008, 25), the construction of the Euromoney rating might pose an endogeneity problem for some of the covariates described in the next section, because factors such as debt level and composition and economic performance are built into the indicator (and thus almost by definition correlated with the country ratings). For this reason, Dreher and Voigt use a modified version of the Euromoney score that extracts three components which are clearly parts rather than determinants of creditworthiness (it is worth noting that Dreher and Voigt report a very high correlation (0.97) between the original and modified ratings). Unfortunately, detailed data that enable the authors to construct a modified rating are only available after 1992; since, following Simmons (2000a, b) and Grieco et al. (2009), my dataset ends in 1997 (and an important robustness check, described below, limits the sample to country-year observations prior to 1992), the Dreher and Voigt solution is too costly for me. However, it is important to note that the explanatory variables I am most interested in—those related to compliance with Article VIII—are not components of either of the two measures of perceptions of credit risk employed in this article.

-

Reliable data on bond spreads are available for only eight emerging markets from 1994 to the present, and sovereign bond ratings by credit rating agencies are available for a smaller number of countries than either IIR or Euromoney scores (see Mauro et al. 2006, 100). Interest rate differentials are another alternative market-based measure of risk, but this indicator has drawbacks: the availability of data on national interest rates is spotty at best, and until the 1990s, own interest rates in most developing countries were not market-determined (Aizenman and Marion 2004, 575). Nonetheless, I used a simple t-test, relying on Aizenman and Marion’s (2004) construction of the interest rate differential (ln[(1 + i)/(1 + i US)], where i US is the US T-bill rate and i is the national deposit rate), to see whether countries that fail to comply with Article VIII pay higher relative interest rates. On average, the logged interest rate differential is almost twice as large for countries that are noncompliant with Article VIII (0.41) than it is for countries in which the noncompliance variable equals zero (0.22). The large t-statistic (6.07) indicates that the difference of means between the two groups (compliant and non-compliant) is highly significant (p = 0.0000).

-

Quinn (1997, 531). See footnote 2 for a description of the actions prohibited by Article VIII.

-

All member countries of the IMF are, in principle, committed to removing restrictions on the current account. However, upon joining the IMF countries are allowed to retain existing restrictions under Article XIV, which sanctions “transitional” arrangements for countries that are not prepared (or are unwilling) to accept sections 2, 3, and 4 of Article VIII. The IMF attempts to persuade transitional countries to join Article VIII, but some members remained under Article XIV for decades—the Philippines, for example, remained under Article XIV for 50 years (IMF 2006). The Executive Board of the Fund agreed in 1992 that the transitional arrangements had been abused and officials became more forceful in encouraging adoption of Article VIII. It is important to note that once a country notifies the Fund of its acceptance of Article VIII obligations it gives up the right—in perpetuity—to retain existing or impose new current account restrictions. The Fund’s Executive Board has the ability, however, to approve short-term restrictions by Article VIII. The decisions by the Executive Board to approve temporary restrictions are confidential. However, as I discuss in detail below, I take steps to attempt to strip out possible “sanctioned renegers” from the analysis.

-

16 percent of all country-year observations in the sample are coded as noncompliant.

-

For example, if a country was in default in each year from 1960 to 1980, Percent Default would take a value of 100 in 1980; if the country began to service its external debt in 1981, the value would decline to 95.2, and if it stayed current on its payments in the next year, the value would decline to 90.9 (since the country was in default for 20 of 22 years in the observation window), and so on.

-

Biglaiser and DeRouen’s analysis of sovereign bond ratings in Latin America tests the effects of indexes of trade and capital market liberalization, financial liberalization, tax reform, and privatization. The results show that trade reform is the only variable that has a strong (positive) effect on perceptions of creditworthiness (Biglaiser and DeRouen 2007).

-

Laevan and Valencia (2008) update the measure of currency crisis originally developed by Frankel and Rose (1996).

-

My interest in explaining differences between countries, the relative invariance of the key explanatory variables, and the fact that my data includes many more units (95 countries at most) than observations per unit (18 for panels without missing data on covariates) imply that the fixed effects estimator is inappropriate (Abrevaya 1997). Plümper and Troeger (2007) propose a solution (the fixed effects vector decomposition estimator) that “allows estimating time-invariant variables and that is more efficient than the FE model in estimating variables that have very little longitudinal variance” (2007, 125). When I re-estimated the models in Table 5 with Plümper and Troeger’s xtfevd routine in Stata 11, I obtained very similar findings; in fact, the coefficient on the noncompliance variable is slightly larger in both the fixed effects vector decomposition regressions and OLS regressions with standard errors that assume clustering by country (due to space considerations, the additional results are not reported here, but are available in the online Appendix that supplements the electronic version of this article).

-

Recall that the dependent variables have been re-scaled so that positive coefficients indicate greater country risk.

-

The finding is consistent with Reinhart et al.’s (2003) contention that defaults in the past make countries more likely to default on their foreign debts in the future, regardless of the level of indebtedness. This result is also consistent with Archer et al.’s (2007) finding that bond ratings are strongly negatively affected by a history of default.

-

Non-random selection is at the core of the debate between Simmons and Hopkins (2005) and von Stein (2005). They are interested in the question of whether Article VIII has an independent effect on state behavior, which is a very different question from the one I ask here, and which makes selection processes a much more pressing concern in their debate.

-

Note that the Shift Left variable is omitted from the first stage because, by construction, it is related to Article VIII status: to capture shifts in government partisanship away from the constellation of interests that produced the decision to sign the agreement, it takes a value of 1 if a country has accepted Article VIII obligations and the ideological makeup of the government subsequently moves to the left.

-

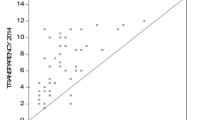

Regional definitions, following Simmons, come from the World Bank’s regional classifications. The level of regional noncompliance should be relatively uncorrelated with a country’s sovereign risk rating: it seems unlikely, for example, that market actors would incorporate information about Peru’s compliance in developing risk assessments for Argentina. Evidence from research on compliance with transparency rules provides support: Glennerster and Shin (2007) examine whether adoption of IMF-led transparency reforms lowers sovereign bond spreads and find that regional adoption of transparency reforms has no effect on borrowing costs.

-

This is implemented in Stata 11 via the cdsimeq command. The method reports correct standard errors when, in a system of simultaneous equations, one endogenous variable is continuous and the other is dichotomous. See Keshk (2003) for details.

-

World Bank, Global Development Finance CD-ROM (2003).

-

World Bank, Global Development Finance CD-ROM (2003).

-

World Bank, Global Development Finance CD-ROM (2003).

-

World Bank, World Development Indicators CD-ROM (2004).

-

World Bank, World Development Indicators CD-ROM (2004).

-

World Bank, World Development Indicators CD-ROM (2004).

-

Monty Marshall and Keith Jaggers, “Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Regime Transitions, 1800–2002,” Center for International Development and Conflict Management (CIDCM), http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/inscr/polity.

-

Fearon and Laitin (2003).

-

Ahlquist (2006).

-

Vreeland (2003).

-

Beck et al. (2001).

References

Abrevaya, J. (1997). The equivalence of two estimators of the fixed effects logit model. Economics Letters, 55, 41–43.

Ahlquist, J. S. (2006). Economic policy, institutions, and capital flows: portfolio and direct investment flows in developing countries. International Studies Quarterly, 50, 681–704.

Aizenman, J., & Marion, N. (2004). International reserve holdings with sovereign risk and costly tax collection. The Economic Journal, 114, 569–591.

Archer, C. C., Biglaiser, G., & de Rouen, K., Jr. (2007). Sovereign bonds and the ‘democratic advantage’: does regime type affect credit ratings agency ratings in the developing world? International Organization, 61, 341–365.

Axelrod, R. (1984). The evolution of cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

Beck, N. (2001). Time-series cross-section data: what have we learned in the past few years? Annual Review of Political Science, 4, 271–293.

Beck, T., Clarke, G., Groff, A., Keefer, P., & Walsh, P. (2001). New tools in comparative political economy: the database of political institutions. World Bank Economic Review, 15(1), 165–176.

Biglaiser, G., & DeRouen, K., Jr. (2007). Sovereign bond ratings and neoliberalism in Latin America. International Studies Quarterly, 51, 121–138.

Blonigen, B., & Wang, M. (2004). Inappropriate pooling of wealthy and poor countries in empirical FDI studies. NBER Working Paper No. 10378.

Bordo, M., & Kydland, F. (1999). The gold standard as a commitment mechanism. In M. D. Bordo (Ed.), The gold standard and related regimes. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bordo, M., & Rockoff, H. (1996). The gold standard as a ‘good housekeeping seal of approval’. The Journal of Economic History, 56(2), 389–428.

Bordo, M., Mody, A., & Oomes, N. (2004). Keeping the capital flowing: the role of the IMF. International Finance, 7(3), 421–450.

Braumoeller, B. F. (2004). Hypothesis testing and multiplicative interaction terms. International Organization, 58, 807–820.

Brewer, T. L., & Rivoli, P. (1990). Politics and perceived creditworthiness in international banking. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 22(3), 357–369.

Büthe, T., & Milner, H. (2008). The politics of foreign direct investment into developing countries: increasing FDI through international trade agreements? American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 741–762.

Chayes, A., & Chayes, A. H. (1993). On compliance. International Organization, 47(2), 175–205.

Chayes, A., & Chayes, A. H. (1995). The new sovereignty: compliance with international regulatory agreements. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cosset, J.-C., & Roy, J. (1991). The determinants of country risk ratings. Journal of International Business Studies, 22, 135–142.

Downs, G. W., & Jones, M. A. (2002). Reputation, compliance, and international law. Journal of Legal Studies, XXXI, 95–114.

Downs, G. W., Rocke, D. M., & Barsoom, P. N. (1996). Is the good news about compliance good news about cooperation? International Organization, 50(3), 379–406.

Drazen, A., & Masson, P. (1994). Credibility of policies versus credibility of policymakers. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109, 735–754.

Dreher, A., & Voigt, S. (2008). Does membership in international organizations increase governments’ credibility? Testing the effects of delegating powers. CESifo Working Paper No. 2285.

Drukker, D. M. (2003). Testing for serial correlation in linear panel data models. Stata Journal, 3, 168–177.

Fearon, J. (1994). Domestic political audiences and the escalation of international disputes. American Political Science Review, 88(3), 577–592.

Fearon, J., & Laitin, D. (2003). Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. American Political Science Review, 97(1), 75–90.

Feder, G., & Ross, K. (1982). Risk assessment and risk premiums in the eurodollar market. Journal of Finance, 37, 679–691.

Frankel, J., & Rose, A. (1996). Currency crashes in emerging markets: an empirical treatment. Journal of International Economics, 41, 351–366.

Friedrich, R. J. (1982). In defense of multiplicative terms in multiple regression equations. American Journal of Political Science, 26(4), 797–833.

Gaubatz, K. T. (1996). Democratic states and commitment in international relations. International Organization, 50(1), 109–139.

Glennerster, R., & Shin, Y. (2007). Does transparency pay? Unpublished working paper, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Grieco, J. M., Gelpi, C. F., & Warren, T. C. (2009). When preferences and commitments collide: the effect of relative partisan shifts on international treaty compliance. International Organization, 63, 341–355.

International Monetary Fund. (2006). Article VIII acceptance by IMF members: Recent trends and implications for the fund. Accessed at: http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2006/052606.pdf.

Jensen, N. (2003). Democratic governance and multinational corporations: political regimes and inflows of foreign direct investment. International Organization, 57, 587–616.

Jensen, N. (2004). Crisis, conditions, and capital: the effect of international monetary fund agreements on foreign direct investment inflows. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 48(2), 194–210.

Keohane, R. (1984). After hegemony. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Keshk, O. (2003). Cdsimeq: a program to implement two-stage probit least squares. The Stata Journal, 3, 1–11.

Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2008). Systemic banking crises: a new dataset. IMF Working Paper WP/08/224 (November).

Lohmann, S. (1997). Linkage politics. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(1), 477–513.

Mansfield, E., Milner, H., & Rosendorff, B. P. (2002). Why democracies cooperate more: electoral control and international trade agreements. International Organization, 56(3), 477–513.

Mauro, P., Sussman, N., & Yafeh, Y. (2006). Emerging markets and financial globalization: Sovereign bond spreads in 1870–1913 and today. New York: Oxford University Press.

McKinnon, R. (1979). Money in international exchange: The convertible currency system. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mearsheimer, J. (1994/95). The false promise of international institutions. International Security, 19, 5–26.

Mitchell, R. (1994). Regime design matters: intentional oil pollution and treaty compliance. International Organization, 48(3), 425–458.

Morgenthau, H. (1978). Politics among nations: The struggle for power and peace (5th ed.). New York: Alfred Knopf.

Mosley, L. (2006). Constraints, opportunities, and information: financial market-government relations around the world. In P. Bardhan, S. Bowles, & M. Wallerstein (Eds.), Globalization and egalitarian redistribution (pp. 87–119). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

North, D., & Weingast, B. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: evolution of institutions governing public choice in 17th century England. Journal of Economic History, 49, 803–832.

Obstfeld, M., & Taylor, A. (2003a). Globalization and capital markets. In M. D. Bordo, A. M. Taylor, & J. G. Williamson (Eds.), Globalization in historical perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Obstfeld, M., & Taylor, A. (2003b). Sovereign risk, credibility, and the gold standard: 1870–1913 versus 1925–31. Economic Journal, 113, 241–275.

Plümper, T., & Troeger, V. (2007). Efficient estimation of time-invariant variables in finite sample panel analyses with unit fixed effects. Political Analysis, 15(2), 124–139.

Quinn, D. (1997). The correlates of change in international financial regulation. American Political Science Review, 91(3), 531–551.

Reinhart, C., Rogoff, K., & Savastano, M. (2003). Debt intolerance. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 1–62.

Sachs, J., & Warner, A. (1995). Economic reform and the process of global integration. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 1–118.

Saiegh, S. M. (2005). Do countries have a ‘democratic advantage?’ political institutions, multilateral agencies, and sovereign borrowing. Comparative Political Studies, 38(4), 366–387.

Schultz, K., & Weingast, B. (1998). Limited governments, powerful states. In R. M. Siverson (Ed.), Strategic politicians, institutions, and foreign policy (pp. 22–23). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Schultz, K., & Weingast, B. (2003). The democratic advantage. International Organization, 57(1), 3–42.

Simmons, B. (1998). Compliance with international agreements. Annual Review of Political Science, 1, 75–93.

Simmons, B. (2000a). The legalization of international monetary affairs. International Organization, 54(3), 573–602.

Simmons, B. (2000b). International law and state behavior: commitment and compliance in international monetary affairs. American Political Science Review, 94(4), 819–835.

Simmons, B., & Hopkins, D. (2005). The constraining power of international treaties: a response to von Stein. American Political Science Review, 99(4), 623–631.

Sinclair, T. (2005). The new masters of capital: American bond rating agencies and the politics of creditworthiness. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Sobel, A. C. (1999). State institutions, private incentives, global capital. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Tomz, M. (2007). Reputation and international cooperation: Sovereign debt across three centuries. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

von Stein, J. (2005). Do treaties constrain or screen? Selection bias and treaty compliance. American Political Science Review, 99(4), 611–622.

Vreeland, J. (2003). The IMF and economic development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wacziarg, R., & Welch, K. (2003). Trade liberalization and growth: New evidence. Unpublished paper, Stanford University.

Wacziarg, R., & Welch, K. (2008). Trade liberalization and growth: new evidence. World Bank Economic Review, 22(2), 187–231.

Waltz, K. (1979). Theory of international politics. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Wooldridge, J. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross-section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT.

World Bank. (2003). Global Development Finance CD-ROM. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (2004). World Development Indicators CD-ROM. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I thank Asaf Zussman, the participants at the graduate student colloquium at Cornell University, the anonymous reviewers and the editor of this journal for very helpful comments. I thank Beth Simmons and Daniel Hopkins for kindly sharing their data on Article VIII compliance. Christopher Way deserves particular thanks for his advice at every stage in the project. Any errors or omissions remain my own.

Appendices

Appendix A: Description of Variables and Data Sources

1.1 Dependent Variables

Institutional Investorrating: ratings reported by Institutional Investor, compiled once yearly (either September or October). Ratings are based on survey responses provided by economists and sovereign risk analysts at leading global banks and securities firms. Responses are compiled, averaged across countries, and weighted by the publication’s perception of the bank’s credit analysis sophistication and global prominence. Countries are scored on a scale from 0 (high risk)–100 (low risk), which is transformed in the article such that 0 (low risk) ➔ 100 (high risk) to ease the interpretation of the coefficients reported in the analysis.

Euromoneyrating: index of “country creditworthiness.” Ratings are based on analytical, credit, and market indicators. The ratings are based on polls of economists and political analysts supplemented by quantitative data such as debt ratios and access to capital markets. The overall country risk score derives from nine separate categories, each with an assigned weighting: (1) political risk (25% weighting)—the risk of non-payment or non-servicing of payment for goods or services, loans, trade-related finance and dividends, and the non-repatriation of capital; (2) economic performance (25% weighting)—based on GNP figures per capita and on results of Euromoney poll of economic projections; (3) debt indicators (10% weighting), including total debt stocks to GNP, debt service to exports, and current account balance to GNP; (4) debt in default or rescheduled (10% weighting)—scores are based on the ratio of rescheduled debt to debt stocks; (5) credit ratings (10% weighting)—nominal values are assigned to sovereign ratings from Moody’s, S&P and Fitch IBCA; (6) access to bank finance (5% weighting)—calculated from disbursements of private, long-term, unguaranteed loans as a percentage of GNP; (7) access to short-term finance (5% weighting); (8) access to capital markets (5% weighting)—heads of debt syndicate and loan syndications rate each country’s accessibility to international markets; (9) discount on forfeiting (5% weighting)—reflects the average maximum tenor for forfeiting and the average spread over riskless countries such as the US. The original ratings are transformed by (100—Euromoney rating) so that 0 (low risk) ➔ 100 (high risk).

1.2 Independent Variables

Article VIII Signatory: dummy variable denoting 1 where countries have accepted Article VIII of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement and 0 if the country is subject only to Article XIV transitional arrangements.Footnote 31

Restriction: dichotomous variable denoting whether a country has imposed restrictions on payments in current account. This measure is taken from the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (1967–1997).

Noncompliance with Article VIII: variable is an interaction term (current account restriction * Article VIII signatory), where 1 equals noncompliance and 0 denotes compliance.Footnote 32

Reserves/debt: Ratio of international reserves to total external debt.Footnote 33

BOP/GDP: Current account balance (the sum of the credits less the debits arising from international transactions in goods, services, income, and current transfers; represents the transactions that add to or subtract from an economy’s stock of foreign financial items), measured in terms of GDP.Footnote 34

Debt/GNI: Ratio of total external debt to gross national product.Footnote 35

GDP Per Capita: Gross domestic product per capita, in constant $US 1995 benchmark.Footnote 36

GDP Per Capita Growth: Annual growth rate of GDP per capita.Footnote 37

Inflation: consumer price index, annual percentage.Footnote 38

Trade openness: the sum of exports and imports, as percentage of GDP.

Regime type: Polity2 measure, taken from the Polity IV project. The Polity2 democracy score computed by subtracting a measure of autocracy, AUTOC, from a measure of democracy, DEMOC; the score ranges from −10 (least democratic) to +10 (most democratic). The AUTOC and DEMOC scores are indexes of scores on different institutional factors (such as the competitiveness and openness of executive recruitment, constraints on the executive recruitment, competitiveness of political participation, etc.).Footnote 39

Political Instability: indicator that is coded 1 if the Polity2 regime type measure changes (either increases or decreases) by at least three points during a three-year period.Footnote 40

Percent Years in Default: a cumulative indicator that records the percentage of years since 1960 that a country was in default.Footnote 41

Openness: an update of the Sachs and Warner openness indicator, the measure takes a value of 1 in periods of openness and 0 if the country is closed. A country is coded as closed if any of the following conditions hold: (1) the average unweighted tariff rate >40%; (2) the average core non-tariff barrier frequency on capital goods and intermediaries >40%; (3) the annual black market premium >20%; (4) the country has a functioning marketing board for a major export good; (5) a socialist economic system.Footnote 42

IMF: variable equals 1 if a country is under an IMF lending program (standby arrangement, extended fund facility, structural adjustment facility, or enhanced structural adjustment facility) and 0 otherwise.Footnote 43

Currency Crisis: variable takes the value of 1 in years in which a country experienced a currency crisis. Laeven and Valencia, building on Frankel and Rose’s (1996) earlier effort, define a currency crisis “as a nominal depreciation of the currency of at least 30% that is also at least a 10% increase in the rate of depreciation compared to the year before” (2008: 6).

Shift Left: dichotomous measure that equals 1 in all country years in which the government in power is to the left of the government that initially signed the Article VIII agreement. In Grieco et al. (2009) coding, positions of governments along the ideological spectrum are drawn from the World Bank’s Database of Political Institutions.Footnote 44 In the words of the authors that created the variable, Shift Left “represents the ideal test of whether shifts away from the configuration of national preferences that produced the original decision to sign Article VIII serve to condition the probability of compliance with the treaty” (Grieco et al. 2009: 346).

Appendix B: List of Countries and Years of Article VIII Noncompliance, 1979–97

Country |

Year of Article VIII Accession |

Year(s) of Noncompliance |

|---|---|---|

ALBANIA |

– |

– |

ALGERIA |

1997 |

1997 |

ANGOLA |

– |

– |

ARGENTINA |

1968 |

1983–93 |

ARMENIA |

1997 |

– |

AZERBAIJAN |

– |

– |

BAHRAIN |

1974 |

– |

BANGLADESH |

1995 |

1996–97 |

BELARUS |

– |

– |

BENIN |

1996 |

1996–97 |

BOLIVIA |

1967 |

1982–86; 1996–97 |

BOTSWANA |

1995 |

1995–96 |

BRAZIL |

– |

– |

BULGARIA |

– |

– |

BURKINA FASO |

1996 |

1996–97 |

BURUNDI |

– |

– |

CAMEROON |

1996 |

1996–97 |

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC |

1996 |

1996–97 |

CHAD |

1996 |

1996–97 |

CHILE |

1977 |

1983–97 |

CHINA |

1996 |

1996–97 |

COLOMBIA |

– |

– |

REPUBLIC OF CONGO |

1996 |

1996–97 |

COSTA RICA |

1965 |

1982–95 |

CROATIA |

1995 |

1995 |

CZECH REPUBLIC |

1994 |

1994 |

DEM. REP. OF CONGO |

– |

– |

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC |

1953 |

1979–97 |

ECUADOR |

1970 |

1983–94 |

EGYPT |

– |

– |

EL SALVADOR |

1946 |

1979–93 |

ESTONIA |

1994 |

– |

ETHIOPIA |

– |

– |

FIJI |

1973 |

1989–92; 1996–97 |

GABON |

1996 |

1996–97 |

GAMBIA |

1993 |

– |

GEORGIA |

1997 |

1997 |

GHANA |

1995 |

1997 |

GUATEMALA |

1947 |

1981–89; 1995 |

GUINEA BISSAU |

1997 |

1997 |

GUINEA |

1996 |

1996–97 |

GUYANA |

1967 |

1979–93 |

HAITI |

1954 |

– |

HONDURAS |

1951 |

1982–93 |

HUNGARY |

1996 |

– |

INDIA |

1995 |

1995–97 |

INDONESIA |

1989 |

– |

IRAN |

– |

– |

ISRAEL |

1994 |

1996–97 |

IVORY COAST |

1996 |

1996–97 |

JAMAICA |

1963 |

1979–95 |

JORDAN |

1995 |

1995–96 |

KAZAKHSTAN |

1996 |

1996–97 |

KENYA |

1995 |

1995 |

KOREA, SOUTH |

1989 |

1996–97 |

KUWAIT |

1963 |

– |

KYRGYZSTAN |

1995 |

– |

LATVIA |

1995 |

– |

LEBANON |

1994 |

– |

LESOTHO |

– |

– |

MACEDONIA |

– |

– |

MADAGASCAR |

1996 |

1996 |

MALAWI |

1996 |

1996–97 |

MALAYSIA |

1969 |

– |

MALI |

1996 |

1996–97 |

MAURITANIA |

– |

– |

MAURITIUS |

1994 |

– |

MEXICO |

1947 |

1983–87 |

MOLDOVA |

1995 |

1995–97 |

MOROCCO |

1993 |

1993; 1996–97 |

MOZAMBIQUE |

– |

– |

NAMIBIA |

1996 |

1996–97 |

NEPAL |

1995 |

1995–97 |

NICARAGUA |

1965 |

1979–95 |

NIGER |

1996 |

1996–97 |

NIGERIA |

– |

– |

OMAN |

1975 |

1996–97 |

PAKISTAN |

1995 |

1995–97 |

PANAMA |

1947 |

– |

PAPUA NEW GUINEA |

1975 |

1995–97 |

PARAGUAY |

1995 |

1996–97 |

PERU |

1961 |

1985–92; 1996 |

PHILIPPINES |

1995 |

1995–97 |

POLAND |

1995 |

1996–97 |

ROMANIA |

– |

– |

RUSSIA |

1996 |

– |

RWANDA |

– |

– |

SENEGAL |

1996 |

1996–97 |

SIERRA LEONE |

1996 |

1997 |

SINGAPORE |

1969 |

1997 |

SLOVAKIA |

1995 |

1995–97 |

SLOVENIA |

1995 |

1995–96 |

SOUTH AFRICA |

1974 |

1979–93; 1994–95 |

SRI LANKA |

1994 |

1996–97 |

SWAZILAND |

1990 |

1996–97 |

SYRIA |

– |

– |

TAJIKISTAN |

– |

– |

TANZANIA |

1996 |

1996–97 |

THAILAND |

1990 |

– |

TOGO |

1996 |

1996–97 |

TUNISIA |

1993 |

1996–97 |

TURKEY |

1990 |

1996–97 |

TURKMENISTAN |

– |

– |

UGANDA |

1994 |

1994 |

UKRAINE |

1997 |

1997 |

URUGUAY |

1981 |

– |

UZBEKISTAN |

– |

– |

VENEZUELA |

1977 |

1984–88; 1994–95 |

VIETNAM |

– |

– |

YEMEN |

1996 |

– |

ZAMBIA |

– |

– |

ZIMBABWE |

1995 |

1995–97 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nelson, S.C. Does compliance matter? Assessing the relationship between sovereign risk and compliance with international monetary law. Rev Int Organ 5, 107–139 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-010-9080-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-010-9080-7