The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic triggered the most severe public health crisis in recent decades. Early research suggested that populist leaders responded to the crisis more slowly, performed poorly and adopted fewer health measures than their non-populist counterparts (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2021; McKee et al. Reference McKee, Gugushvili, Koltai and Stuckler2021). While studies on ‘medical populism’ shed light on how populist leaders perform on issues of public health (Lasco Reference Lasco2020), little comparative research has been conducted on their communication strategy amid public health crises in general and the COVID-19 pandemic in particular (Cervi et al. Reference Cervi, García and Marín-Lladó2021; Manfredi-Sánchez et al. Reference Manfredi-Sánchez, Amado-Suárez and Waisbord2021; Rufai and Bunce Reference Rufai and Bunce2020). How do populist leaders communicate with voters during such crises? We address this question by studying the communication strategies of right-wing populist leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic and analysing if their rhetorical style, as well as public discourse, changed after the outbreak of the coronavirus.

Scholars have already noted that populist leaders tend to perpetuate crises for electoral gain rather than managing them (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2015). In line with the extant scholarship, we assume that the rhetorical style of populist leaders serves as the fundamental component of their crisis management. The populist communication strategy serves as a convenient tool to reframe crises to help leaders bring a sense of urgency to their diagnoses, downplaying the public risks and mobilizing popular support to challenge their political opponents. In particular, Twitter serves as a major communication venue for leaders to disseminate information on the coronavirus, promote official policies and boost public morale (Rufai and Bunce Reference Rufai and Bunce2020). Based on a detailed analysis of their Twitter accounts, this article explores the communication strategies used by three right-wing populist leaders, namely, Boris Johnson (UK), Donald Trump (US) and Narendra Modi (India), to address medical emergencies and maintain popular support during the COVID-19 pandemic even at times when their governments failed to perform well.

Our findings suggest that the pandemic has exposed significant differences among right-wing populist leaders' communication and crisis management strategies. All the leaders in our sample initially downplayed the pandemic, but while Johnson and Modi revised their positions, Trump continued to ignore warnings from government agencies, discounted advice from medical experts (Rutledge Reference Rutledge2020) and used Twitter systematically to shift the blame onto other actors. Once they acknowledged the severity of the crisis, Johnson and Modi emphasized different aspects of government policies towards the pandemic, possibly due to the distinct needs and sensitivities of their electorate. Naturally, the three leaders have all sought to promote their administration's crisis management strategies, but only Trump resorted to excessive self-praise. By contrast, Modi and Johnson promoted their own government and parties during the global pandemic. Our findings are consistent with extant studies on these leaders' policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neither Modi nor Johnson have subscribed to an anti-science discourse and avoided advice of the medical community, as was the case with Trump. In sharp contrast to the other two leaders, Trump consistently downplayed the threat posed by the coronavirus, discounted advice from the medical experts and ignored repeated warnings from government agencies and advisers (Rutledge Reference Rutledge2020).Footnote 1 The frequency of Twitter use and the tone of the language that the three leaders employed reflected this variation in their policy agendas and communication styles. While populism is still a useful framework, other political factors played a more important role than is generally recognized in the extant scholarship in influencing their communication policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Populist leaders have some leeway in deciding to acknowledge a crisis and promoting a policy response. Our findings demonstrate the need for more research that could shed light on the conditions under which an issue will come to dominate the communication agenda of populist leaders.Footnote 2 By improving our stock of knowledge on the rhetorical strategies of three right-wing populist leaders, this article seeks to contribute to the scholarship on medical populism and political communication.

Populist communication style

Although populism has become a global trend in recent years (Mudde Reference Mudde2004), scholars disagree on how best to define it. Whereas some characterize populism as a thin-centred ideology that purports to represent the will of the masses (Mudde Reference Mudde2004), others conceptualize it as a strategy of political mobilization from above (Roberts Reference Roberts2006; Weyland Reference Weyland2001), a political discourse (Laclau Reference Laclau2007) and a performative (Moffitt and Tormey Reference Moffitt and Tormey2014) and sociocultural frame (Ostiguy Reference Ostiguy, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Ostiguy and Roberts Reference Ostiguy and Roberts2016). Despite their differences, scholars usually agree that populists divide society into two homogenous and antagonistic groups – the ‘pure’ people and the ‘corrupt’ elites – and perceive politics as a Manichean fight between the two groups (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013; Stavrakakis et al. Reference Stavrakakis, Katsambekis, Nikisianis, Kioupkiolis and Siomos2017).

It is argued that populists have a distinct ‘communication style’ (Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007: 3) that centres on popularizing content – including dramatization, personalization and simplificationFootnote 3 – and building strong emotional bonds with supporters. Stylistically, populists emphasize the sovereignty of the people, attack the elite and ostracize others (Bracciale and Martella Reference Bracciale and Martella2017). In doing so, they stress their similarity with the people, promote a sense of unity and praise their achievements and virtues. Right-wing populists especially identify enemy groups that they distinguish from the ‘people’ and ostracize for political purposes (Bracciale and Martella Reference Bracciale and Martella2017: 7; Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007: 324).

Populists have a complicated relationship with the media. While they criticize mainstream media for being out of touch with the masses and target journalists, they benefit from media coverage to spread their views and reach out to new voters (Engesser et al. Reference Engesser, Ernst, Esser and Büchel2017). On the other hand, populists have skilfully used social media to cultivate their brands and expand their personal audience (Ernst et al. Reference Ernst, Engesser, Büchel, Blassnig and Esser2017; Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Sandberg and Spierings2020). Online populist communication owes its growing importance to several factors. First, through it populists can gain unmediated access to the masses by circumventing the journalistic gatekeepers (Engesser et al. Reference Engesser, Ernst, Esser and Büchel2017). Its format is most suitable for crafting simplistic and short messages for larger audiences. The speed and virality of online communication serve as another motivating factor for populists to rely on social media (Engesser et al. Reference Engesser, Ernst, Esser and Büchel2017: 1286; Jacobs and Spierings Reference Jacobs and Spierings2019). However, we do not suggest that populists use social media more frequently than non-populists. Rather, online communication serves as a powerful tool for populists to promote their brand of politics to the wider public.

Crisis performance and the COVID-19 pandemic

In line with Arjen Boin (et al. Reference Boin, Hart and McConnell2009: 83–84), we define crises as events or developments widely perceived by members of relevant communities to constitute urgent threats to core community values and structures. A sizable amount of literature links crises to populism (Laclau Reference Laclau2007; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2015). For instance, Ernesto Laclau claims that some level of crisis may even be a precondition for the rise of populism since it provides a rupture in hegemonic discourses and practices (Laclau Reference Laclau2007: 177). Populists are highly skilled at spreading the notion of failure, linking the crisis to the entire political system and offering simplistic solutions to overcome the existing crisis. In what Henrik Bødker and Chris Anderson term the ‘politics of impatience’, populist leaders capitalize on the anger and disillusionment felt by voters against the slow response of democratic institutions (Bødker and Anderson Reference Bødker and Anderson2019). Hanspeter Kriesi et al.'s (Reference Kriesi, Pappas, Aslanidis, Bernhard and Betz2016) study of 17 European countries validates these claims, showing that populist parties increased their support during the 2008–2009 global financial crisis. In sum, crises provide fertile ground for challenging the establishment and expanding electoral support by reaching out to worried or disillusioned voters (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2015; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013; Stavrakakis et al. Reference Stavrakakis, Katsambekis, Nikisianis, Kioupkiolis and Siomos2017).

Benjamin Moffitt (Reference Moffitt2015: 194) rightly claims that these studies treat the crisis as an external trigger of populism rather than one of its internal features. Populist leaders do not merely benefit from a crisis after it breaks out; instead, they perform a crisis to serve their political interests (for some examples, see Cervi Reference Cervi2020; Cervi and Tejedor Reference Cervi and Tejedor2021). As Rogers Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2021: 7) puts it, ‘populists do not simply respond to pre-existing crises; they seek to cultivate, exacerbate, or even create a sense of crisis, casting the crisis as one that they alone have the power to resolve’. Therefore, the crisis is not a neutral event but is politically mediated. Moffitt (Reference Moffitt2015: 208–209) claims that populist performance during a crisis differs from ‘crisis politics’ in general. First, populists divide ‘the people’ from those nefarious actors who are portrayed as the chief culprits of the crisis in the first place. Second, populists push for the ‘continued propagation and the perpetuation of crisis’ to achieve political success. Moffitt (Reference Moffitt2015) highlights six steps in the populist performance of crisis: (1) identify failure; (2) elevate to the level of crisis by linking into a wider framework and adding a temporal dimension; (3) frame ‘the people’ versus those responsible for the crisis; (4) use media to propagate performance; (5) present simple solutions and strong leadership; and (6) continue to propagate crisis.

While elucidating how political and economic crises catapult populists to power, existing studies neglect to look at how populists deal with the crises that break out during their time in office. We suggest that populists in power may have a strong incentive to treat crises differently than when they were in opposition. This is especially the case for crises such as natural disasters and public health emergencies, whose origins cannot easily be blamed on the populists' domestic opponents. In these cases, populist leaders are less likely to identify failures and elevate them to the level of crisis since they are expected to resolve the problem at hand as the incumbent. Arguably, social media use becomes even more crucial for populists in power. During the crisis, these leaders need to perform through media to control how the public perceives the crisis, downplay its impact and salience and demonstrate that they are performing successfully. They have a strong incentive to downplay the severity of the crisis while manipulating outcomes to exaggerate their success.

The nature of the COVID-19 pandemic further complicated the efforts of populist leaders to perform during the crisis. The origins of the coronavirus do not translate into the dichotomous framework of the populist discourse. Although Trump did portray the coronavirus as the ‘China virus’, it would have been near impossible to accuse domestic actors of the outbreak of the pandemic. In this sense, COVID-19 acted like a natural disaster rather than a political crisis that could be managed by a populist leader. As a result, populist polarization on this issue occurred on the type and level of measures against the virus and vaccine mandates. Instead of seeking to perpetuate the crisis, many populist leaders downplayed the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic, defied scientific advice and accused opposition politicians and media of creating unnecessary panic (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2021). According to cross-national studies, populist governments, on average, delayed acknowledging the severity of the coronavirus, adopted fewer health measures and distributed smaller stimulus packages during the global pandemic (Katsambekis et al. Reference Katsambekis, Stavrakakis, Biglieri, Sengul, De Cleen, Goyvaerts and de Barros2020; Toshkov et al. Reference Toshkov, Carroll and Yesilkagit2021). Instead, some populist leaders capitalized on the opportunity to suspend rights, prohibit anti-government protests and expand their powers (Alizada et al. Reference Alizada, Cole, Gastaldi, Grahn, Hellmeier, Kolvani, Lachapelle, Lührmann, Maerz, Pillai, Staffan and Lindberg2021). This strategy indeed fits in with their tendency to centralize power, attack their opponents and use a polarizing discourse (Esen and Yardımcı-Geyikçi Reference Esen and Yardımcı-Geyikçi2019; Weyland Reference Weyland2020).

Do populists in power strategically react to and perform crises as they do in opposition? If so, what communication strategies do they employ? Crises are a regular fixture of modern politics. The three leaders analysed in this article had already faced numerous crises that they used to promote their own brand of politics and reshape the political arena. Before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump administration was confronted with several international crises with authoritarian governments in North Korea and Venezuela and the influx of refugees from Central America on the US–Mexico border. Similarly, Johnson dealt with the Brexit crisis, and Modi experienced serious domestic (Muslim riots) and international (deteriorating relations with Pakistan) crises.Footnote 4 However, the coronavirus offers a unique opportunity to address these questions since the pandemic affected all three countries during the same period. Since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic in March 2020, all countries have rushed to develop policy responses. Due to its global impact, the COVID-19 pandemic thus offers the possibility to compare the variation in the rhetorical strategy and communication policy of populist leaders during the same period.

Based on the populism literature, we expect right-wing populist leaders to: (1) increase their Twitter use during the global pandemic since Twitter enables leaders to communicate directly with the public to share critical information about the pandemic and boost public morale; (2) praise their government's fight against the pandemic; (3) adopt an over-optimistic tone to keep national sentiment high; (4) openly question or challenge the scientific advice of their medical experts; (5) attribute blame to other actors and criticize their opponents; and (6) tap into the widespread public anger against lockdowns and other pandemic-related restrictions. Instead of acknowledging the complexity of the situation and offering sound medical advice, populist leaders are also likely to position themselves as ‘straight-shooters’ with simple and effective solutions against the coronavirus. The following section describes the research design to test these expectations. Due to the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic, the populist leaders may be constrained in their efforts to set terms of the public debate in this crisis. This populist strategy proved challenging because populist leaders could not easily respond with their existing ideological narratives and accuse domestic actors since the exogenous nature of the coronavirus resembled a natural disaster (Lacatus and Meibauer Reference Lacatus and Meibauer2021: 4). Furthermore, the need to rely on scientific advice to fight the coronavirus has placed right-wing populist leaders, who are prone to espouse anti-scientific and anti-intellectual views, in a politically difficult position of working together with the medical community. Faced with an unprecedented public health crisis, we also expect right-wing populist leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic to engage in various levels of rhetorical adaptation by acknowledging the severity of the crisis and endorsing some medical advice from the scientific community to limit political risks while resorting to their usual tactics of blaming others for mismanagement, targeting their opponents and engaging in self-praise.

Cases and research design

This article focuses on the communication strategy of right-wing populists on Twitter during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Right-wing populists espouse an ‘exclusionary’ understanding of the people while portraying cultural, religious, racial or linguistic minorities as the ‘other’ (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013). In response to these self-proclaimed threats, they adopt an eclectic agenda that merges nativist and socially conservative policies with interventionist economic measures (Otjes et al. Reference Otjes, Ivaldi, Jupskås and Mazzoleni2018). In line with their nativist style, many right-wing populist leaders blame foreign actors and their domestic allies for their country's troubles (Hameleers et al. Reference Hameleers, Bos and De Vreese2017; Kessel and Castelein Reference Kessel and Castelein2016). Anti-intellectualism is also widespread among these politicians, who rail against technical and academic expertise embodied by what they consider the intellectual establishment (Mede and Schäfer Reference Mede and Schäfer2020). While earlier studies devoted more attention to the rhetoric of populist politicians in news media, recent research has shifted focus to their use of social media such as Twitter and Facebook (Kristensen and Mortensen Reference Kristensen and Mortensen2021: 2445). The extant scholarship characterizes the right-wing populist communication strategy as highly personalized and centred on leaders (Krämer Reference Krämer2017: 1298). Although personalization of politics is a widespread phenomenon seen among all types of politicians, populist leaders use social media with great skill to circumvent journalistic gatekeepers (Engesser et al. Reference Engesser, Ernst, Esser and Büchel2017) and thrive on developing a crisis narrative to further their political interests (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2015).

Our article adopts an ‘actor-centric’ approach (de Vreese et al. Reference de Vreese, Esser, Aalberg, Reinemann and Stanyer2018: 428) to focus on the Twitter accounts of three right-wing populist leaders – Donald Trump, Boris Johnson and Narendra Modi – who were in power when the pandemic broke out. President Trump stands out because of his background in the business world. Despite having little experience in politics, Trump excelled in using Twitter to initiate a political movement, solidify his popularity within the Republican base and target his opponents (Lawrence and Boydstun Reference Lawrence and Boydstun2017; Şahin et al. Reference Şahin, Johnson and Korkut2021). Modi is a career politician and former chief minister of Gujarat, who became the prime minister (PM) of India from the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in 2014. Although he differed from Modi and Trump, Johnson did not fully adopt anti-elite rhetoric. Many scholars consider Johnson a populist due to his personality-driven politics, anti-EU rhetoric and defiance of the British parliament to ‘get Brexit done’. Despite his elite background, Johnson adopted a populist discourse as a Eurosceptic journalist and later politician within the Conservative Party, which eventually paved the way for his rise to Downing Street. During the Brexit talks, Johnson reshaped the Conservative Party to mobilize widespread public frustration and anti-popular sentiment over the failure to achieve a deal with the EU (Ward and Ward Reference Ward and Ward2021: 14). These three leaders emerged against a background of rising economic inequality and cultural backlash in their respective countries. They also regularly use Twitter and tweet in English. Among the three leaders, Johnson's earlier career as a journalist may have given him a more acute sense of the importance of Twitter.Footnote 5 Focusing on these cases allows us to shed better light on the stark similarities and subtle differences among right-wing populist leaders. There is already a substantial body of research on the rhetorical strategies of right-wing leaders (Berti and Loner Reference Berti and Loner2021; Ernst et al. Reference Ernst, Engesser, Büchel, Blassnig and Esser2017; Lacatus and Meibauer Reference Lacatus and Meibauer2021; Şahin et al. Reference Şahin, Johnson and Korkut2021), though many of these works lack a comparative framework and rarely focus on communication policy during a public health crisis.

In this project, we collected English tweets of the three populist leaders using Twitter's API (Twitter Inc. 2020a, 2020b) from 1 June 2019 to 31 December 2020, to explore how their communication style and tone changed during the pandemic. The selected Twitter accounts are @realDonaldTrump (Donald J. Trump, the president of the US 2017–21), @BorisJohnson (Boris Johnson, the prime minister of the UK 2019–22) and @narendramodi (Narendra Modi, the prime minister of India since 2014).

To examine the change in social media usage before and after the outbreak of the pandemic, the collected tweets were processed for inspection. The textual content of the post was processed to extract their significant elements, such as their words, hashtags and mentions. Hashtags organize discussions around a specific theme and give visibility to that theme, making it easier to identify relevant discussions to interested parties. Therefore, the initiation and the consistent use of a hashtag signal their intention to emphasize a particular theme. Similarly, mentions indicate specific users or organizations that are of specific interest to the poster.

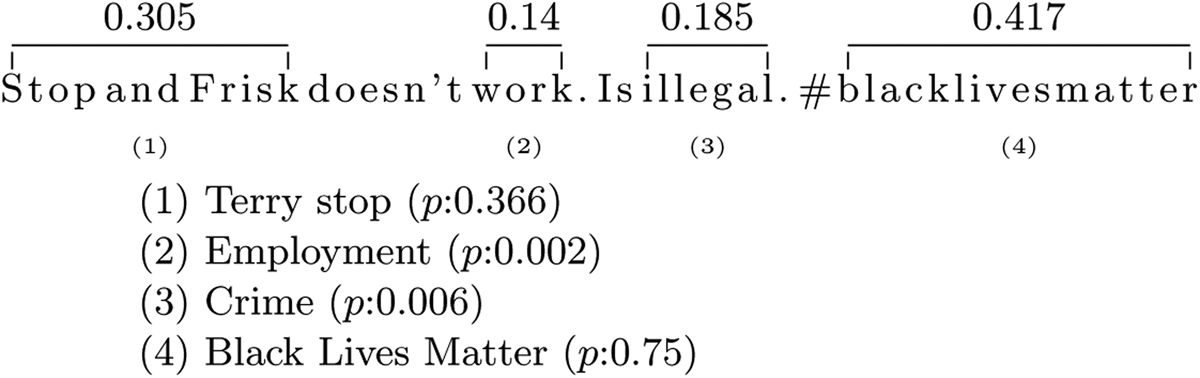

To track the significance of these elements from a collective and dynamic perspective, word clouds (after eliminating stop words)Footnote 6 and temporal graphs are generated, respectively. Entity linking is used to extract a unique reference to concepts that may be articulated differently. The tweet content is also subjected to entity linking (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Wang and Han2015) using the TagMe API Documentation (TagMe 2018) to identify and link entities within tweets to external resources in Wikipedia. Figure 1 shows a sample entity linking using TagMe.

Figure 1. The Entities Linked to the Tweet: Stop and frisk doesn't work. Is illegal. #blacklivesmatter

Our analysis has three steps: first, we look at the shift in Twitter use after the outbreak of the pandemic by examining the number of tweets (including tweets and retweets) during the period mentioned above. Second, we extract the textual data from these tweets to explore the three leaders' political vocabulary using word clouds and entity networks. Word clouds consist of a weighted list of words, where font size indicates the importance or occurrence frequency in the text data (Burch et al. Reference Burch, Lohmann, Beck, Rodriguez, Di Silvestro and Weiskopf2014). Third, we examine hashtags and mention use. Hashtags organize the discussion around a certain theme and serve to give visibility to that theme, which makes it easier to identify relevant discussions to interested parties (Page Reference Page2012). Therefore, political leaders' starting or using a certain hashtag signals their intention to emphasize a particular theme.

Results

We begin by examining whether the pandemic has changed populist leaders' social media use. We chose 30 January 2020, when the WHO reported human-to-human transmission of the virus outside China and warned the international community about global risk, to demarcate the period before and after the pandemic (Belvedere Reference Belvedere2020). We did not start the analysis on 11 March 2020 – when the WHO officially declared the COVID-19 infection as a global pandemic – because infections had already spread in the US, India and the UK, forcing these states to adopt travel restrictions.

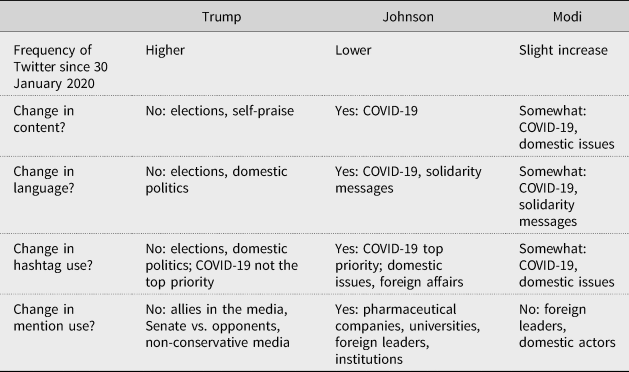

Table 1 reports changes in populist leaders' Twitter use before and after 30 January 2020. As portrayed in Table 1, the pandemic affects the leaders' Twitter use unevenly. While Trump almost doubled his Twitter use, Modi's Twitter use remained about the same, but Johnson's Twitter use decreased. Trump's frequent Twitter use during the pandemic supports existing studies that argue Trump uses Twitter as a fundamental tool of his discursive governance to discipline the federal bureaucracy, roll back government regulations and set policy narratives (Şahin et al. Reference Şahin, Johnson and Korkut2021). We examine the distribution of tweets over time in Figure A1 (see Online Appendix). Specifically, we look at whether tweets issued on peak dates are related to COVID-19. In Trump's case, tweets on 22 January concerned the impeachment. Tweets from 5 June revolve around fake news, the Democrats and the economy. On 30 August Trump tweeted about the Black Lives Matter protests and elections. The remaining peaks relate to the 2020 elections. In Johnson's case, the highest number of tweets is observed in 2019, well before the pandemic. Finally, Modi tweeted most on 17 September 2019, and 2020, on his birthday. Thus, in none of the cases are peaks COVID-related.

Table 1. Populist Leaders' Twitter Use before and after 30 January 2020

Content of messages

This section analyses tweet content using word cloud and entity network analyses to ascertain whether the pandemic has generated any differences. Word clouds highlight the most frequently used words in textual data. Therefore, they are appropriate for pinpointing emphases in leaders' messages. Figure A2 in the Online Appendix represents findings from the word cloud analyses. Trump's top words are ‘president’ and ‘great’ before and during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, Trump frequently employs ‘democrats’, ‘people’, ‘impeachment’, ‘Trump’, ‘fake’ and ‘news’. During the pandemic, his focus is on his 2020 presidential campaign. Therefore, he predominantly mentions himself and the presidential candidate from the Democratic Party, Joe Biden. When addressing his supporters in this period, Trump also uses emotional and positive words such as ‘thanks’ or ‘great’. These findings substantiate the idea that Trump employs a populist communication style emphasizing people, his presidency and his opponents (including Biden and the media outlets that produce ‘fake news’). The coronavirus enters Trump's parlance after 30 January but never becomes nearly as frequent as ‘Trump’, ‘president’ or ‘great’. Overall, presidential elections shape Trump's discourse on social media, not the pandemic.

The data in Figure A2 in the Online Appendix suggest a stark shift in focus in Johnson's discourse on social media following the pandemic. While his pre-pandemic discourse revolves around Brexit (get Brexit done, #getbrexitdone), it centres on the coronavirus after the pandemic has begun. Johnson's pre-pandemic social media discourse qualifies as a populist style; the most frequent words are ‘country’ and ‘people’ followed by opposition actors (Jeremy Corbyn) and Johnson's party. In the aftermath of the pandemic, ‘National Health Service’, ‘lives’, ‘protect’, ‘coronavirus’ and ‘people’ become the most recurrently used words. Noticeably, Johnson more frequently refers to people during the pandemic. He also primarily employs words with positive and emotional connotations to foster solidarity during the pandemic. Thus, unlike Trump, Johnson focuses his social media discourse on the coronavirus. Johnson's sensitivity about the coronavirus can be attributed to the high number of deaths during the early months of the pandemic. However, it is noteworthy that American society suffered similarly significant losses, but the death toll did not warrant a similar shift in Trump's discourse.

The data in Figure A2 in the Online Appendix suggest a moderate shift in Modi's social media discourse following the start of the pandemic. COVID-related topics occupy a central place in Modi's tweets in 2020. However, ‘India’, ‘people’ and ‘thank’ have high salience also before the pandemic. This observed continuity reinforces the hypothesis that Modi's discourse features the populist themes theorized in the literature (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013). As a matter of fact, of the three leaders, Modi most frequently references his people and country and most recurrently employs words with positive connotations (e.g. thank, well, wish, excellent, Ji, best, progress) when engaging with the public on social media. Modi is also the most performative of the three leaders and carries this performativity onto social media. Notice that ‘yoga’ has high salience before the pandemic because Modi rallies supporters by presiding over collective public social events associated with the Hindu culture like yoga or meditation and builds a personality cult linked with Hindu symbols. Since the pandemic hindered the organization of collective public events, Modi has been capitalizing on rallying solidarity around the fight against the coronavirus (#indiafightscorona), which further substantiates Modi's populist communication style. Overall, like Johnson, Modi acknowledges the significance of the coronavirus risk.

We further examine our data by constructing entity networks. Nodes in entity networks are entities, and edges represent two entities mentioned in the same tweet. Node size is proportional to the frequency with which an entity appears in tweets. Edges are weighted by the frequency of a pair of entities appearing in the same tweet. Figures A3 through A5 in the Online Appendix represent the entity networks of Trump, Johnson and Modi tweets.

Before the pandemic, the most central nodes in Trump's profile are the impeachment, the Democratic Party, articles of the impeachment, the US and hoax. The edges carrying the highest weights are the impeachment–Democratic Party, impeachment–hoax, impeachment–Fox News, impeachment–Republican Party and impeachment–witch hunt. These findings suggest that Trump is conveying that the impeachment process was a hoax conjured up by the Democratic Party. The edges that carry the second heaviest weights reinforce this inference; impeachment–case closed and impeachment–Ukraine. These findings parallel the results of the word cloud analysis: Trump's social media discourse revolves around the future of his re-election, with a focus on refuting allegations against his presidency by representing them as biased accusations. During the pandemic, the most central nodes are the Second Amendment to the US Constitution, the US, Republican Party, Democratic Party and the coronavirus. Although the coronavirus has a high salience, it still is secondary to presidential elections. The edges carrying the highest weight are Sleepy Joe–Joe Biden, China–virus, Democratic Party–Republican Party, Joe Biden–far-left politics as well as the US–Fox News. These findings reinforce the earlier finding that elections, not the coronavirus, shape Trump's discourse. The entity networks further reveal that by linking the coronavirus to China, Trump attempts to shift the blame onto an outside actor. Finally, reflecting the populist strategy of elite-bashing and polarization, Trump belittles his opponent in the presidential elections by calling him names and mischaracterizing his stance as far-left politics. Some populist leaders like Trump and Brazil's Jair Bolsonaro resort to personal attacks and character assassination (Berti and Loner Reference Berti and Loner2021).

In Johnson's case, entity networks parallel the word cloud analysis; Brexit-related concepts shape the PM's pre-pandemic discourse, and COVID-related issues shape his discourse in 2020. In 2019, when the Brexit negotiations were ongoing, Johnson's social media discourse centres on removing roadblocks. Hence, the highest degree nodes are United Kingdom's withdrawal from the European Union, National Health Service, European Union, Conservative Party, British people and referendum. Following the pandemic, the most central nodes in Johnson's tweets are the coronavirus, United Kingdom, pandemic, National Health Service and Prime Minister's Questions. Strikingly, the entity network of the pandemic period displays a link between sovereignty and the United Kingdom, which may be referring to Brexit. Yet, it is the coronavirus that shapes Johnson's social media discourse in 2020. Overall, Johnson's Twitter use departs from Trump's by the conspicuous absence of the belittling of his opponents, elite-bashing and blame-shifting.

Turning to Modi, the entity network of the pre-pandemic period is partitioned, but the largest subgraph is a star network centred around India. India has the highest degree of the overall entity network, which parallels the word cloud analysis finding that ‘India’ is the most recurrent theme in Modi's tweets. In the star network, all nodes that connect to ‘India’ represent foreign actors. In contrast, the other smaller subgraphs feature nodes that represent domestic actors or issues, for example, the ‘Indian Space Organization’, ‘Indian Council for Cultural Relations’, ‘Parliament of India’ and ‘Jammu and Kashmir’. These patterns do not change during the pandemic. The largest subgraphs of the entity network during the pandemic are again a star network with ‘India’ at the core and foreign actors (e.g. the president of the United States and the Maldives) at the periphery. The predominance of foreign actors in Modi's entity network is explained by how Modi uses Twitter to communicate with foreign leaders while he communicates with his electorate through television. Overall, there is continuity in Modi's social media discourse; India is the most frequent theme. The coronavirus enters Modi's vocabulary rather than changing the entire discourse – as is the case with Johnson.

Targeting a particular discussion or community: hashtag use

This section analyses the use of hashtags to see whether the pandemic has prompted the three leaders to revise their communication strategy to address the major public health crisis. Twitter hashtags allow users to sift through tweets to access a particular topic of discussion, gain insight on trending topics and participate in public debates on Twitter (Enli and Simonsen Reference Enli and Simonsen2018: 3–4). They therefore inform us about the nature of politicians' communication strategies to reach out to voters and set the agenda. Politicians use hashtags strategically by choosing trending hashtags to gain visibility and raise new issues (Christensen Reference Christensen2013).

Figures A6, A7 and A8 in the Online Appendix represent the most common hashtags Trump, Johnson and Modi used before 30 January 2020. For Trump, we constructed one plot depicting the most popular hashtags of his tweets and another one listing the most popular hashtags of his tweets and retweet combined. This comparison highlights the differences between the messages that Trump prefers to convey personally and the ones he wants to circulate without directly being associated with the content. These differences, if they exist, help us to diagnose whether Trump retweets in order to increase the ‘virality’ of certain messages that the traditional media ignores, as Kristof Jacobs and Niels Spierings (Reference Jacobs and Spierings2019: 1686) claim. We did not construct separate plots for Johnson's and Modi's tweets and retweets, because plots differed only in Trump's case – hashtags for retweeted tweets by Johnson and Modi are available in the Online Appendix.

The priority for Trump before and after the pandemic is his presidential campaign. Trump's favourite hashtags before the pandemic are #MAGA (Make America Great Again) and #KAG2020 (Keep America Great). #MAGA also appears at the top of the hashtag list that includes retweets. These findings are not surprising in that these mottos are the most famous slogans of Trump's 2016 presidential campaign, which Trump continued to use during his presidency.Footnote 7 Other popular hashtags relate to issues on his campaign agenda (e.g. #2A (the Second Amendment)) or campaign slogans (#SaluteToAmerica, #TRUMP2020, #KeepAmericaGreat, #TrumpRallyDallas). The remaining hashtags concern foreign summits (e.g. #G7Summit or #G7Biarritz) and domestic issues (e.g. #LESM (law enforcement social media)). On the other hand, the hashtag list including retweets features a greater variety of topics, including #USMCA (the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement), #hurricaneDorian, #Dday75thAnniversary, #SocialMediaSummit or #Gutfeld (the Greg Gutfeld Show on Fox News). Overall, Trump's tweets centre on his presidential campaign, whereas his retweets have a wider span from foreign policy to current domestic affairs.

The pandemic does not change Trump's priority. His favourite hashtags during the pandemic are again #MAGA, #2A, #KAG2020, #KAG, #VOTE and #MakeAmericaGreatAgain. Notably, most of his campaign-related hashtags can be classified under three categories: those that are linked to his election campaign mottos (e.g. #Trump2020, #AmericaFirst, #Trump, #TrumpPence, #RNC2020, #Debate2020, #SaluteToAmerica), those linked to his conservative supporters in the media (#Fox News, One America News Network (#OANN)) and those relating to his political opponents (#DemDebate, #PelosiTantrum, #ObamaGate). The COVID-related hashtags, namely #CARESact (8th in the rankings), the #COVID19 (16th), #PPPloan (Paycheck Protection Program loan) (18th) and #Coronavirus (32nd), conspicuously have lower priority. The #COVID-19 comes second in the hashtag list for retweets, which also contains #CARESact, the #Coronavirus and #PPP – that is, social programmes that the Trump administration developed to alleviate the adverse economic implications of the pandemic. Thus, the other aspects of the pandemic (e.g. #coronavirus or #Coronavirus) come to light only through Trump's retweets. Other popular retweeted hashtags pertain to policy issues on his campaign agenda – for example, the Second Amendment (#2A), the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (#USMCA), #impeachment, #NDAA (National Defense Authorization Act), #LESM (law enforcement social media), #SCOTUS (Supreme Court of the United States), #NC09 (the 9th District of North Carolina), #TX13 (the 13th District of Texas).

Johnson's favourite hashtags before the pandemic relate to Brexit. The PM attempted to convey his government's resolve to finalize the UK's withdrawal from the European Union; that is, #GetBrexitDone, #LeaveOct31st, #TakeBackControl or #VoteConservative. The emphasis on Brexit is partly due to the high salience of the issue in European and domestic politics and partly because the failure of the previous government under Theresa May to conclude the UK's withdrawal from the EU contributed to Johnson's rise to the premiership. Johnson's second favourite set of hashtags concerns foreign affairs (e.g. #G7, #UNGA) or domestic issues of both a political and non-political nature (e.g. #StAndrewsDay, #ArmisticeDay, #SmallBusinessSaturday). During the pandemic, Johnson primarily employs the COVID-related hashtags – #StayAlert, #coronavirus, #StayHomeSaveLives or #HandsFaceSpace – to underscore the importance of personal precautions in combatting the coronavirus. Other coronavirus-related hashtags praise healthcare workers (e.g. #OurNHS and #ThankYouNHS) to foster solidarity and cooperation. It is worth remembering that Johnson had been advocating for herd immunity at the onset of the pandemic (Buchan Reference Buchan2020). Hence, the PM reverted to his original position, making the coronavirus the central theme of his social media discourse. In effect, Johnson uses a few non-coronavirus-related hashtags related to history and public memory (e.g. #WindRushDay, #BattleofBritain80) or popular issues for the British electorate (e.g. #LonelinessAwarenessWeek, #ClimateAction).

Finally, Modi's favourite hashtags of the pre-pandemic period include #MannKiBaat, #YogaDay19, #HowdyModi, #FitIndiaMovement and #RepublicDay. Mann Ki Baat is a monthly television programme wherein Modi answers people's questions. #MannKiBaat's overwhelming popularity confirms the hypothesis that populist leaders use social media to increase their visibility. Similarly, #Yoga and #FitIndiaMovement are the frequently used hashtags because Modi organizes collective social gatherings and activities to rally popular support and create a sense of community.

These findings reveal that Modi uses a populist communication strategy centred around the leader and furnished by themes that allude to the Hindu culture. Other popular hashtags indeed concern Indian sociopolitical culture (e.g. #Diwali, #InternationalTigerDay, #Gandhi150, #ConstitutionDay) or issues appealing to nationalist allegiances (e.g. #TeamIndia, #SingaporeIndiaHackathon). During the pandemic, Modi's hashtag use diversified. Not only is COVID-19 the top hashtag, but the top five hashtags overwhelmingly feature measures to contain the coronavirus (e.g. #JantaCurfew, #9pm9minute). Significantly, 9pm9minute is a collective symbolic act whereby Indian people turn off the lights for nine minutes to show unity in India's fight against the coronavirus. On the other hand, Modi continues to employ hashtags related to Indian cultural heritage (#MannKiBaat, #NewIndiaFitIndia, #YogaDay). Another striking finding is that many non-COVID-19-related hashtags concern social assistance and economic programmes, such as #AatmaNirbharVendor (loans to street vendors), #SampatiSeSampanta (distribution of property cards), #AtalTunne (the construction of the Atal Tunnel) and #NamamiGange (a conservation and rejuvenation programme of the River Ganges), through which Modi signals his government's efforts to alleviate abject poverty and promote development. Thus, Modi deliberately engages with themes related to Hinduism, his leadership and his policies. The coronavirus enters his vocabulary but does not change his focus.

Overall, the hashtag analysis pinpoints what the leaders deem to be the most important issues. These issues are the presidential elections for Trump, Brexit for Johnson and Hindu culture and his government's social policies for Modi. The pandemic substantively changes Johnson's social media discourse, which is not the case for Trump and Modi (although the latter acknowledges the importance of the pandemic, unlike the former). Our results partially corroborate the study by Gunn Enli and Chris-Adrian Simonsen (Reference Enli and Simonsen2018), which demonstrates that the most frequently used hashtags among politicians are media-centric, referring primarily to journalists and popular radio and TV programmes. Of the three leaders studied here, only Trump repeatedly referred to conservative news channels and media figures, while Modi merely promoted his weekly programme. To reach out to voters directly, populists like Modi and Hugo Chávez of Venezuela appeared on their radio and television programmes, and Trump frequently participated in Fox News shows. Similarly, Trump effectively used his Twitter account to promote radio and TV programmes supportive of his agenda and to comment on debates in the mainstream media. In so doing, Trump did not merely ‘operate under the brands of existing media hashtags’ (Enli and Simonsen Reference Enli and Simonsen2018) but also set the public debate. In contrast to Enli and Simonsen (Reference Enli and Simonsen2018), who claim that politicians are more inclined to retweet hashtagged content than journalists, we find a high degree of variation among politicians – even populists.

Next, we analyse the use of mentions in leaders' tweets to understand who leaders intentionally call upon. Figures A9, A10 and A11 in the Appendix show mentions for Trump, Johnson and Modi. Before and during the pandemic, Trump mentions conservative media and journalists, including Fox News, foxandfriends, OANN, Sean Hannity, Maria Bartiromo and Tucker Carlson. Fox News, which supported Trump's campaign in the 2016 presidential elections and beyond, receives the most mentions. Mainstream media and journalists also figure in Trump's tweets – for example, CNN and the New York Times – albeit less frequently than the conservative ones. Earlier research has demonstrated that populist politicians effectively use Twitter to put journalists under pressure through public naming and shaming (Krämer Reference Krämer2017; Waisbord and Amado Reference Waisbord and Amado2017). Indeed, Twitter's open network structure allows politicians to criticize journalists directly and publicly, which any user can see (Bossetta Reference Bossetta2018: 488; Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Sandberg and Spierings2020: 614). This function puts journalists on the spot, draws attention to their work and may even prompt politicians' supporters to attack journalists directly. On other occasions, populists engage in ‘shaming without naming’ (Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Sandberg and Spierings2020: 615) by sharing accusative tweets about the media without explicitly mentioning a particular journalist. Our findings on Trump's social media use have thus far supported these theories, although the content of these mentions needs closer inspection. Scholars have pointed out that Trump frequently employs anger-based appeals to his supporters (Wahl-Jorgensen Reference Wahl-Jorgensen2018: 768). Interestingly, Trump mentions conservative journalists more than he mentions his critics, which suggests that he might be seeking to shape his coverage in the conservative media as well. Second, conservative senators supporting the Trump administration, such as Lindsay Graham, also received frequent mentions in Trump's tweets.

The list of mentions in his tweets and retweets overwhelmingly features Trump's Twitter account, @realDonaldTrump, as Trump retweets those who mention him. In effect, @realDonaldTrump is mentioned three times more than the second most mentioned entity, the White House. This parallels the previous finding that Trump is distinctly self-referential, unlike the other leaders in our sample. Other mentions in Trump's retweets echo mentions in his tweets; conservative media outlets, such as Fox News and foxandfriends, conservative politicians and advisers (e.g. Dan Scavino, the GOP leader, the GOP chairwoman). During the pandemic, Trump's top mentions still feature the conservative media outlets (Fox News) and even those that disseminate conspiracy theories (Breitbart News), and conservative politicians, followed by the non-conservative media outlets whom Trump is known for accusing of bias against his presidency (CNN, New York Times). Also, realDonaldTrump and the White House continue to be the top mentions, reinforcing the earlier point about Trump's self-referential attitude. Unlike before the pandemic, Trump mentions Joe Biden but not nearly as frequently as he mentions himself. In sum, Trump focuses more on his persona than his public office and mentions his supporters in the conservative media and the Senate more frequently than his critics.

Johnson is not an avid user of mentions – the highest number of mentions is seven before the pandemic and eight after. When he uses mentions, Johnson mentions his party more than himself (BackBoris), unlike Trump. His other mentions include conservative politicians (e.g. Jeremy Hunt), foreign leaders or actors (e.g. Scott Morrison, EU co-president) or domestic actors who are popular in public debates, such as veterans or the English rugby team. During the pandemic, Johnson's top mentions are the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), Oxford University (because of its vaccine research) and pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer and BioNTech. These findings buttress the centrality of the coronavirus in Johnson's social media discourse. On the other hand, Johnson is much less self-referential than Trump.

Modi uses mentions more frequently than Johnson, but the two leaders display similar mention patterns. Modi's most frequent mention is also his party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP4India). Unsurprisingly, Modi's other mentions concern foreign leaders or institutions, including realDonaldTrump, the United Nations, or the prime minister of Bhutan, because Modi uses Twitter as a communication tool in foreign policy. The pandemic does not change this pattern in that foreign leaders continue to receive most mentions. Noticeably, realDonaldTrump gets twice as many mentions as Modi's party, and other foreign actors are also mentioned more frequently than the BJP.

To recap, our findings, as summarized in Table 2 below, suggest continuity in Trump's social media discourse. The latter remains focused on the presidential elections even after the pandemic. In contrast, Johnson shifts his focus to the coronavirus, away from Brexit. Modi continues to employ Twitter mainly as a communication tool in foreign policy. Modi uses Twitter to capitalize on his leadership and policies when it comes to domestic politics. The coronavirus enters his vocabulary without restructuring his Twitter habits. Both Modi and Johnson use the coronavirus as an opportunity to cultivate solidarity, whereas the coronavirus risk is secondary to Trump's presidential campaign. Second, both our hashtag and mention analyses reveal that Trump is distinctly self-referential in his social media use (Trump tweets and uses mentions and hashtags to bring his persona to the fore). In contrast, Modi and Johnson, albeit populist, prioritize their parties. Trump's style can best be summarized as ‘champion of the people’ due to his negative communication style and political/campaign communicative focus.Footnote 8 Trump's tone contains issue simplification and emotional appeals, primarily focusing on his political career. Modi, on the other hand, employs an ‘intimate’ style that is both positive and personal. He directly reaches out to his people by tweeting about communal events and non-political programmes to bring together the Indian nation and foreign leaders to seek interstate cooperation during the pandemic. Lastly, Johnson has an ‘engaging’ style that lies at the intersection of positive communication and the political/campaign focus. He engages the British public in political topics, promotes his party and mobilizes his base during this public health crisis. This strategy has allowed him to boost public morale and praise the successes of his government and the British healthcare system. Based on our findings, we conclude that Trump, Modi and Johnson exhibit sharply different styles of communication on Twitter both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2. Has the Leaders' Use of Twitter Changed since the Outbreak of the Pandemic?

These differences warrant closer scrutiny of the content and style of their messages to shed more light on the communication strategies of right-wing populist leaders. This variation reinforces the view that crises are politically mediated. As incumbents, populist leaders had to maintain a balance between being responsive to their electoral base and addressing the COVID-19 pandemic. As the only leader with an electoral challenge in 2020, Trump faced more serious limitations among the three leaders in adjusting his discourse during the global pandemic. Accordingly, Trump relied more heavily on self-praise, engaged in blame-shifting and attacks against the media and his opponents, and refrained from following the advice of his medical experts. In the US, there was a huge discrepancy between the number of COVID-19 patients and deaths in major urban areas and in sparsely populated towns in the countryside during the first months of the pandemic. Since the coronavirus disproportionately hit vulnerable minority groups affiliated with the Democrat Party, many Trump supporters remained sceptical about the severity of the pandemic (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2021: 3). Their scepticism enabled Trump to contest coronavirus restrictions, attack scientists and political opponents, and push for the early removal of restrictions to limit the negative economic impact of the pandemic. Facing an electoral contest that year, Trump preserved his communication policy to meet the expectations of his voters and prioritized domestic themes related to the campaign.

In contrast to Trump, the other two leaders had more leeway for rhetorical adaptation and shifted their focus to the coronavirus after the outbreak of the pandemic. In Britain, an escalating death toll of COVID-19 and the British electorate's conscientiousness towards this health risk may explain why Johnson abandoned the herd immunity strategy, highlighted his government's measures, and became very vocal in emphasizing Britain's unity in the fight against COVID-19. Thanks to his landslide electoral victory in December 2019, Johnson could adjust his communication policy to address the public outcry against the rising human toll of the pandemic in the UK.

Indian voters fell between the two extremes, which explains why Modi incorporated pandemic-related issues into his discourse. Modi's discourse before the pandemic revolved around solidarity, which the leader rallied by promoting collective social activities like yoga. However, during the pandemic, Modi also shifted focus to COVID-related messages and devised novel collective social activities to forge solidarity in the fight against COVID-19. He also promoted bilateral cooperation efforts with other leaders in the international arena.

Conclusion

This article conducted one of the first systematic analyses of the communication strategies of right-wing populist leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic based on the content of tweets collected from the Twitter accounts of Trump, Johnson and Modi between 1 June 2019 and 31 December 2020. This study contributes to existing studies on populist communication and medical populism by demonstrating the existence of high variation among the communication styles and tones of right-wing populist leaders during the global pandemic. Initially, all three leaders downplayed the severity of the coronavirus, but Johnson and Modi soon changed their official positions and communication strategies after the early stages of the pandemic. Boris Johnson took the coronavirus most seriously, which may partly be explained by the heightened sensitivity of the British electorate towards the pandemic. Modi also addressed the severity of the global pandemic but the coronavirus added to the main themes of his existing discourse (i.e. the Hindu culture and foreign policy). Meanwhile, Trump continued to de-emphasize the health risk as he was primarily preoccupied with the 2020 presidential elections.

We further find a significant variation in the intensity and patterns of Twitter use among the three leaders. Trump – already an avid Twitter user – intensified his Twitter use during the pandemic. While he did not come anywhere near Trump, Modi also increased his Twitter use. By contrast, Johnson's Twitter use attenuated after the outbreak of the pandemic. Although all three leaders used emotionalized language to address the pandemic, Johnson and Modi preferred to share supportive messages. Trump took a more negative tone against the scientific community, his political opponents and even China. Of the three leaders, only Trump targeted the media and used hashtags to attack journalists and his political opponents. While all leaders engaged in some form of promotion, Trump chose to highlight himself and promote his campaign, and Modi and Johnson prioritized their governments and political parties.

The hashtag and mention analyses revealed similar patterns. We found that Trump was distinctly self-referential in his social media use compared to Johnson and Modi. These differences are evidence of the political difficulties faced by right-wing populist leaders during the global pandemic. We argue that these leaders sought to strike a balance between remaining responsive to their electoral base with their right-wing populist rhetoric and addressing the public health crisis. Our analysis matches existing research that suggests that the ability of populist leaders to engage in rhetorical adaptation is constrained by their electoral platforms and voter expectations of consistency (Lacatus and Meibauer Reference Lacatus and Meibauer2021).

There are several avenues for future research on this topic. Our study focused on the supply side of populist communication by assessing how right-wing populist leaders have framed the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of content and style. In line with calls for understanding the demand side of populist communication, there is much need to analyse how voters react to populist messages on social media. Based on a systematic collection of tweets and hashtags, new research should assess which messages generated support and anger among voters. To control for national-level factors, this study should be replicated on non-populist leaders to better identify the fundamental elements of the populist communication style during the pandemic. The extant literature alludes to significant differences in policy choices on trade, foreign policy and migration between left- and right-wing populist governments. Did the communication strategy of left-wing populists such as Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela differ from their right-wing counterparts during the COVID-19 pandemic? This research should be expanded to include the communication strategies of centrist and left-populist leaders both in power and in opposition on Twitter and other digital platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and TikTok.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2022.34.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Muhammed Sen for his invaluable assistance on this project, and the attendees of the workshop of the Mitchell Centre for Social Network Analysis.