Spike Lee is sitting in the lobby of the Royalton Hotel in midtown, looking back and forth between the menu and his Louis Vuitton personal agenda, rubbing his head and trying to make some choices. He has just returned from one of many trips to New Orleans to film his documentary When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts, and he is leaving again soon for Germany, to see the final games of the World Cup (today he wears a shirt that says Brazil, the country he’s rooting for). He has to figure out when he’s going to meet with former New Orleans mayor Marc Morial, and he’s got to show up at a 9 a.m. panel tomorrow for the Black Women’s Leadership Council, and what is he going to eat?

Lee mutters his decision. “I’ll take the jumbo lump crab cakes.”

The waiter, who is about 25, black, and obviously unnerved by the fact that he’s waiting on Spike Lee, says, “What?”

“Jumbo lump crab cakes, man!” says Lee, impatient.

The waiter skitters off as if he is a crab himself.

Spike Lee is not the warmest guy in the world. He may not even be the warmest guy in the Royalton. He cares about people, but it’s unclear how much he likes them.

Things are going well for Lee, though, that much he admits. Sort of. “I’m happy, but I’m still … I mean, no one’s going—no one in their sane mind—is going to laugh or make light of the box- office success of a film like Inside Man,” Lee’s latest, which had the biggest opening of his twenty-year career. “Denzel’s biggest opening, too,” Lee is quick to add. “But coming in, I always had the thought that if this film, by some chance, became the big hit it has become, I would be able to get the financing to get this Joe Louis project going, and that still hasn’t been the case.” Which is a pisser, but then Lee did get his Katrina documentary made, all four hours of it, and that’s something.

“What was discouraging to me was, some people—it was like a revelation: I never knew we had poor people in this country,” before Katrina. “I think the United States government has done a very good job of covering up the poor so unless you really, really … You might see a homeless person, you know, on the street, but you can avoid it. You can bypass a lot of stuff,” says Lee, twisting the diamond stud in his ear. He speaks slowly, deliberately, like a professor or a certain kind of pot smoker. It’s a dispensation, not a discussion; he does not look you in the eye.

“Katrina pulled that away, all that cover, left it bare like a raw, exposed nerve,” he says, and starts to pick up a little steam. “And I don’t think we should try to slide it under the rug and act like it doesn’t exist. And I don’t think we’re ever going to get to the place where this country can … I don’t think we’ll ever achieve our true greatness.”

He is silent for a second and stares into space and then, “We’ve still not dealt with slavery!” His words come in a rush. “Black, African-American, and white Americans, we still have not dealt with slavery! When kids are in school and they’re learning about motherfucking George Washington, say the motherfucker owned slaves!” He is still sitting but bouncing, vibrating on the balls of his bright- yellow, brand-new Nikes. “Say what Christopher Columbus did! Kids are still learning in-1492-he-sailed-the-ocean-blue bullshit. George Washington could never tell the truth; he did chop down that motherfucking cherry tree. All right. Get rid of that shit and say he owned slaves. Say the first president of the United States owned slaves! Let’s stop with the lies. Let’s talk about the genocide of the Native Americans! All right, if you don’t want to talk about black and white, all right, let’s leave that aside. Let’s talk about the blankets with smallpox that were given to Native Americans. Let’s talk about the landgrab. I want to make a movie about Custer. I want to show Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull kicking ass!”

Lee’s own children attend one of the top private schools in the city, and he says it’s no better there, where they are among the very few black students in any given class. “We got to come back and go over incorrect shit they get in school all the time! My daughter, she’s like Angela Davis,” he says with pride and starts laughing. “She’s like, ‘Power to the people!’ ”

Spike Lee is not an idiot. He knows there are other interesting things on planet Earth besides race, and he has made movies—25th Hour, Inside Man—where it’s barely an issue. But it is obviously Lee’s primary project to tell stories about African-Americans, specifically stories he thinks are being ignored or obfuscated. And only slightly less amazing than the fact that Lee is the only person who has been consistently doing that in film over the past two decades is the fact that people still think he is street when the foyer of his Upper East Side townhouse has been photographed for Town and Country.

The animating forces of his artistic universe are injustice, prejudice, oppression. But the defining characteristics of his material universe are luxury, access, and success. That’s fine; there’s nothing wrong with being a limousine liberal. It’s better to be a rich person who gives a shit about poor people than it is to be a rich person who only cares about himself.

But it’s interesting how thoroughly Lee seems to have shunned the manners and social methods of the successful. One wonders how his curt, almost diffident manner plays on the Upper East Side, where Lee is surrounded by the social world his wife detailed in her best- selling 2004 novel, Gotham Diaries.

He snorts. “Not my world.”

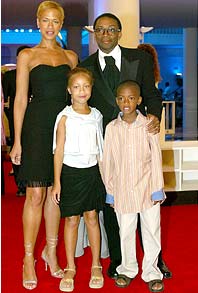

Tonya Lewis Lee looks like she was crafted completely out of caramel. Caramel skin, caramel hair, even her green eyes have a buttery quality. She just spent the weekend with her daughter, Satchel, and her parents at their house in Stamford, Connecticut; Spike is away in Germany with their son, Jackson, at the World Cup. On her ears, Lewis Lee wears little diamond soccer balls.

She greets the host at Fred’s restaurant at the top of Barneys by name. The restaurant is around the corner from her townhouse, so she eats here all the time. (The Lees bought their 9,800-square-foot Italian- palazzo-style home from Jasper Johns in 1998; it was originally built for a Vanderbilt.) The host points out LeBron James seated in the corner, and Lewis Lee says, “Tell him I say hello.” Once, a friend of hers, a woman who is “married to a big muckety-muck,” made a scene here because she was given a bad table before the host knew the woman was meeting Lewis Lee for lunch. The woman had the muckety-muck try to get the host fired. Lewis Lee sent him flowers.

Like Lauren Thomas, the heroine of Gotham Diaries, Tonya Lewis Lee has beautiful manners imparted to her by strict and very prominent parents. Her father, George Lewis, the highest-ranking black executive at Philip Morris during his 34-year career there, was featured in a Fortune magazine cover package last year under the headline PIONEERS. He is a member, along with Vernon Jordan and American Express CEO Kenneth Chenault, of the Boulés, the most elite social club for black men in this country. (Martin Luther King Jr. and W.E.B. DuBois were members.) Lewis Lee’s mother is a member of the Links, a group thus described by Lawrence Otis Graham in Our Kind of People: Inside America’s Black Upper Class: “For fifty years, membership in this invitation-only national organization has meant that your social background, lifestyle, physical appearance, and family’s academic and professional accomplishments passed muster with a fiercely competitive group of women who—while forming a rather cohesive sisterhood—were constantly under each other’s scrutiny.”

And like Lauren Thomas, Lewis Lee sometimes finds the demands of society and philanthropy tiring. “I don’t really like asking for money because I don’t really like being asked for it,” she says over a plate of grilled asparagus. “I get hit up so much … person after person. And no matter how much you give, you can’t win: A year later, you will only receive a solicitation for more instead of a thank-you note.” Still, Lewis Lee serves as vice-chair of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (she is an attorney herself and practiced with the former firm Nixon, Hargrave, Devans & Doyle in Washington, D.C., before she married Spike and moved to Brooklyn), and she has raised money for education programs at the Met and for Kids for Kids. She knows it is her duty: noblesse oblige.

Lewis Lee broke an unspoken code by exposing her social circle in Gotham Diaries. Traditionally, African-American society likes to keep a low profile. There is a certain anxiety that flaunting will lead to backlash. (Of course, there are exceptions, like Black Enterprise publisher Earl Graves—also a Boulé—who keeps a customized fleet of luxury vehicles at his home in Sag Harbor and can most often be spotted cruising around in his Rolls-Royce.) But like her husband, Lewis Lee felt she had untold stories of the black experience to tell. “I wanted to put out there that there is this group of people who exist, because you don’t see them,” she says. “So often, when blacks are depicted as having money, it’s as if they want to be white. And I’m sure there are those who do this.” But there is also a world, an ignored but not imaginary world, that Lewis Lee was raised in and her husband is new to: the Blackristocracy.

“I’ve seen Spike evolve in terms of wanting to do things and go to things,” she says. The first year they were married, for example, she attended the annual gala for the Studio Museum in Harlem, the highlight of the fall calendar in black society, without him.

“I went with my parents because Philip Morris is a big supporter,” she says. “It was a Yankee game that night. Spike Lee didn’t go.” (Lee takes great pleasure in driving around Martha’s Vineyard—Red Sox territory—in his pin-striped Mustang customized with the Yankees’ interlocking NY. “You should see their faces!” he says.

He also flies an enormous Yankees flag from his house there, which happens to be located at the eighteenth hole of a golf course. “They hate it. Hate it!” he says. “That’s all right.” He whispers: “I just love seeing their faces.”)

In fact, Lewis Lee met her husband at another event she was attending because of her Philip Morris ties. It was a dinner for the Congressional Black Caucus: “My father insisted I go to represent the family,” she says. She and Spike crossed paths and immediately noticed each other. “I was going up the stairs, and he was going down the escalator. He was with a date—of course, some women would have no respect, but I did. But he came back around, and he was like, ‘Who are you here with? Do you have a date? Do you have a boyfriend?’ He said, ‘Why don’t you have a boyfriend?’ I said I just haven’t met the right guy yet. He did a little jig.” On their first date, he took her to the party for Madonna’s book Sex. “You know what’s so funny? He was really ready to commit.”

Lee immediately asked her to accompany him to his house in Oak Bluffs, a vacation destination on Martha’s Vineyard for wealthy African-Americans since the thirties, where Lee had a house built in 1992 when he was making Malcolm X. (Asked to describe the residence, Lee says, “Big.”) It was a technique Lee had employed with less success a few years earlier on the model Veronica Webb, whom he cast as his wife in Jungle Fever. Webb wrote about the experience in her book, Sight: “Spike is putting sexual pressure on me. I don’t like it. I hate it. Tomorrow he wants me to go to Martha’s Vineyard with him. The guy just won’t take no for an answer.”

Webb complained that “like a lot of young powerful men, Spike had a case of ‘kingitis,’ where the world revolves around their every wish and whatever’s in the way of their wishes is a complete and utterly unworthy lump of shit as far as they’re concerned.” If Lee’s bedside manner was aggressive, it was also effective: Webb ended up dating him for a year. Tonya Lewis became his wife.

The last thing Lillian and George Lewis wanted was for their daughter Tonya to marry “an entertainment type,” she says. “Philip Morris is a conservative corporation,” and it didn’t help that “Spike is mum.” Anyone who finds this confusing and imagines that Tonya Lewis was marrying up when she wed the famous director Spike Lee is not initiated in the mores of African-American society.

“It’s become more of a meritocracy in the last fifteen years or so, but prior to that, it was really about your family history,” says E.T. Williams, a retired real- estate investor and art collector who was in George Lewis’s chapter of the Boulés and comes from an African-American family that has been prosperous—and, by the way, free—since the late 1700s. Williams is an acquaintance of Spike and Tonya Lewis Lee’s; he last saw them for lunch in Jamaica, when he and his wife, Auldlyn, were staying at the Ritz- Carlton and the Lees were vacationing at the Half Moon. He has been on boards including MoMA, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Central Park Conservancy. He became close with Brooke Astor after she gave a lunch to introduce him to her vacation crowd on Dark Harbor off the coast of Maine.

Though E.T. Williams grew up in Brooklyn, he never met Spike Lee until after he’d married Tonya Lewis. Spike Lee’s family, says Williams, “wasn’t social … Put it that way. His father was professional, if I’m not mistaken—a nice, middle-class family.” Spike’s father, Bill Lee, is a jazz composer who scored several of his son’s early films. His mother was a teacher who died when Spike was a sophomore at Morehouse College in Atlanta, where he was a third- generation legacy. (Lee’s second film, School Daze, was a delirious musical about life at the prestigious black men’s school. There is a memorable song-and-dance number in which light- skinned black women call their darker-skinned rivals “jigaboos” and the dark- skinned women sing the retort “wannabes.”) The Lees were well-to-do, yes; Blackristocracy, no.

“Entertainment was never considered for us,” Williams continues, in a phone call from his house in Sag Harbor, where Tonya Lewis’s parents were also members of the tight-knit community of elite black summer people when she was growing up. “Entertainment conjures up fast living and drugs, which was not what this group was about. One of the few people who became an entertainer from our set was Lena Horne.”

And so the Lewises were skeptical of the man who’d directed She’s Gotta Have It and Do the Right Thing when their daughter fell in love with him. “After my wedding,” says Lewis Lee, “my mother told me, ‘We sent you here in a black limousine and you’re leaving in a white one.’ ”

Williams says he thinks Spike Lee is “brilliant, and he made a brilliant move when he married Tonya Lewis. He knew by marrying her he would get the family, the background, the support, the playing golf with the grandfather in Florida where they winter. I’m sure it’s very important to him, as it should be. He’s off doing his entertainment.”

Lee is, by all accounts, a dedicated father. He flew home from the New Orleans set of When the Levees Broke to be with his son for the night of his birthday; he calls both his children several times a day. And Tonya Lewis Lee is a formidable wife. When she tired of living in the Fort Greene neighborhood where her husband grew up, she told him, “You can stay in Brooklyn. But I won’t be there.” Before he went to Germany with their son a few days ago, she said, “If anything happens to Jackson, you don’t get on the plane. Do not come home.” But, she says, Spike lives up to the nickname his mother gave him for being difficult. (His birth certificate says Shelton Jackson Lee.)

There is a scene in Malcolm X in which Betty Shabazz cries to her husband that he’s always working, that his cause always seems to trump his responsibilities at home. In the director’s commentary on the film, Lee says that it’s an age-old fight, one that he’s had with his own wife many times.

Lewis Lee agrees that it’s an ongoing struggle but says she doesn’t think the comparison to Betty Shabazz and Malcolm X is fair: “Spike is not as malleable as Malcolm.”

There are no white people on Lee’s set today. Everyone is either black or pink.

The sun here in New Orleans seems to be everywhere, and the wet, filthy heat feels like a subway platform at rush hour on the worst day of August. And it’s only May.

Hurricane season starts on June 1, in about two weeks, and Colonel Lewis Setliff, the (pink) spokesman for the Army Corps of Engineers, is telling Lee on- camera that the Corps will be ready. Yesterday, he was quoted on CNN saying they would not.

Setliff is in full fatigues and combat boots, shuffling in front of the debris of the destroyed 17th Street Canal flood wall. Across the street, there is a row of houses that look like they’ve been chewed in half by gigantic wild animals: Roofs have collapsed, furniture and plumbing and wires stick out like veins. “Construction is not complete, but protection is restored,” says Setliff, upbeat. “We’re providing repairs that actually enhance the system, so on June 1, the people of New Orleans will have a hurricane-protection system that’s better and stronger and much more resilient! In some places, they’ll actually have more protection than existed prior to Katrina.”

“You’re talking about pre- Katrina levels?” says Lee, who stands in the sun behind the camera, wearing a baseball cap, green track pants, and bright-blue Nikes.

Setliff motions at the crumbled flood wall behind him. “We weren’t happy with how these performed,” he says. He’s not making a joke.

Later that day, Lee’s crew tapes a woman named Phyllis LeBlanc inside a government-issue trailer, which sits on the front yard of her squashed house. LeBlanc says that on the night of Katrina, “it was like it sucked all the air out of the city. It was, like, womblike shit. Beyond Africa hot. They keep saying, ‘Go back to Africa.’ If Africa is hot like this? Hell, no!” LeBlanc was trapped in her house by the storm surge during Katrina and ultimately rowed out with an elderly neighbor and two children in an empty refrigerator. She has nightmares about the water coming back.

On the banks of the Mississippi, Lee interviews a young woman named Kimberly Polk who had been looking for her daughter for the nine months since Katrina. A few days ago, she identified the 5-year-old’s body.

Lee drives past dozens of houses with their roofs folded in like crumpled cardboard, with the number of dead found inside spray- painted on the front, with signs that say HELP! HELP! all over them. On the side of a brick building near the Utopia Park church, someone has written in giant letters HOPE IS NOT A PLAN.

It’s all so insane, so bad, so unsubtle. Black people waiting on their roofs in the liquefying heat for rescue that never comes. Children drowning in the streets. Old women left to rot on the steps of the Convention Center while the director of FEMA announces on national television that he’s somehow unaware of the 25,000 people waiting there for help. Condi at Ferragamo. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police showing up on horseback in New Orleans before the National Guard. Massive crowds herded into the Superdome and left for days on end without food or water or sewage. And the fat, rich, white mother of the president saying—actually saying!—“This is working very well for them.”

After “Mo’ Better Blues”’s scabrous portrayal of Mo and Josh Flatbush, “B’nai Brith and the Anti-Defamation League were on my ass,” says Spike Lee. “When they’re on you, you know it.”

It’s all so over-the-top. It’s like a Spike Lee movie.

There is plenty to be disgusted with in this country; there is no shortage of inconvenient truths. And Lee also happens to be angry from the inside out.

When he appeared on the Chris Rock show in 1999 after he came out with Summer of Sam, Lee stalked onstage in his black leather jacket and goatee to a shrieking audience of fans. “You’re an icon, Spike,” said Rock. “You make more movies than everybody else, you got courtside seats to the Knicks, you got the beautiful wife, the kids: Why are you so mad?”

“That’s not me,” Lee replied, smirking. “That’s the way I’ve been portrayed.”

Rock snorted. “No, we’ve seen you mad, Spike. We’ve seen you on TV just complaining all the time.” The crowd roared. “They ain’t laughing because I’m lying,” said Rock. “Spike, you’ve been mad for about twelve, fifteen years now. You’re like Khalid Muhammad with a little Afro. You the maddest black man in America.”

It’s hard to picture the maddest black man in America brunching with fellow Upper East Siders Al Roker and Deborah Roberts (as he and his wife do regularly) or leaning on the marble Art Nouveau mantel of his drawing room described in Town and Country.

But most Americans have no real sense of the black upper class beyond bling and Cristal, season tickets to the Knicks, and … white limos. They think of P. Diddy rather than, say, Ken Chenault—a good friend of Spike and Tonya Lewis Lee’s who makes a cameo in Gotham Diaries as the “baron of black society” that he is. “I just think it’s a matter of lack of awareness,” says Chenault. “People tend to be very parochial. And the reality is that the representation and the name recognition have been more in entertainment and sports; the advancement of African-Americans in business has been more recent.”

Within the Blackristocracy, Lee’s indignation is largely regarded as righteous, not embarrassing. The black upper class is still black: Most members have experienced racism at some point in their lives; most recognize it in action in their country all the time. “It’s very much understood,” says E.T. Williams. “We’re all going through it. The historian John Hope Franklin, now an emeritus at Duke, belonged to the Cosmos Club in Washington, D.C., and he had a group coming to celebrate his 85th or 90th birthday. This white lady came up to him and handed him her glass and said, ‘Would you take this?’ And he said, ‘No, madam. If you look, you’ll see the people who work here are in uniform.’ So we can all understand his feelings.”

In the Blackristocracy, Lee’s interest in inequity is not perceived as obsessive: It’s seen as responsible. “If one just starts off with W.E.B. DuBois’s focus on the Talented Tenth, there was always a view that that group had the obligation to help society, and that clearly is a hallmark of Spike—and Tonya,” says Chenault.

Of course, there’s a little more to it than that. In Bamboozled, Lee does a funny, mean, fair spoof: He creates a white character called Timmi Hilnigger, who appears in his own ads flanked by writhing, half- naked black women and says, “If you want to never get out of the ghetto, stay broke, and continue to add to my multimillion-dollar corporation, keep buying my gear!” On the director’s commentary, Lee tells the following story: “A couple weeks ago, I had just dropped my daughter off at school. On the corner of 63rd and Central Park West, Tommy Hilfiger comes up to me.” Lee puts on a pathetic whine of a white-guy voice: “ ‘Oh, Spike, I want you to know I’ve done so much for black people. Oh, Spike, how could you do this? I’ve been giving money at the Martin Luther King fund; every summer I send ghetto black kids to the camp.’ I was waiting for him to say, ‘Spike, I’m blacker than you!’ ”

Even when he is the aggressor, he is the victim.

Lee says there is “a law you cannot have any Jewish person who is not a hundred percent honest” in a film, “because if they are not, you’re anti- Semitic and perpetuating stereotypes.”

There is, however, a fair amount of ground between a hundred percent honest and the moneygrubbing, fast- talking caricatures Mo and Josh Flatbush, the villains of Lee’s Mo’ Better Blues, who got Lee on the shit list of various critics and Jewish organizations. “B’nai Brith and the Anti- Defamation League, they were on my ass,” he says. “You don’t know what it is for someone to get on your ass until B’nai Brith and Anti- Defamation League … You know that shit, when they’re on you, you know it.”

Eventually Lee placated his persecutors by writing an op-ed piece for the Times, but the whole thing still makes him mad when he thinks about it. And the truth is, he’s not sorry about portraying Mo and Josh Flatbush as Jewish bloodsuckers, feeding off the talents of black musicians. “Here’s the thing, though: It’s more than being a stereotype,” says Lee. “In the history of American music, there have not been Jewish people exploiting black musicians? In the history of music? How is that being stereotypical? For me, that’s like saying, like the NBA is predominantly black. Now, if that makes me anti- Semitic …” For a minute, he actually engages and sort of laughs. “I’m not writing any more op-ed pieces,” he says. “I did it once. I’m not doing it again. Seriously. I’m not doing it again.”

If you watch all twenty of Lee’s films, you’ll notice several trademarks. First, there is his signature shot, an actor traveling on a dolly with the camera, which makes the world seem to recede behind the subject. (There are only a handful of directors who’ve developed their own shot like that, something that’s taught in film schools.) Then, of course, there’s Lee’s fascination with stereotypes and categories: He loves a good procession. The most famous is what’s referred to in the screenplay for Do the Right Thing as “The Racial Slur Montage,” during which Lee’s character calls Italians “dago, wop, garlic breath,” an Italian calls blacks “gold-chain- wearing, fried- chicken-and-biscuit-eating monkeys,” and a Latino guy calls Koreans “ slanty-eyed, me-no-speak- American, own every fruit and vegetable stand in New York.”

The idea of all the bigotry in the city exploding in front of the camera seems to delight Lee. He directed a similar scene in 25th Hour, in which Edward Norton’s character, contemplating leaving the city for prison, holds forth on what he won’t miss about all the different ethnic and social groups in New York: cabdrivers are “terrorists in training—slow the fuck down.” There are the “Puerto Ricans on welfare rolls” and “the uptown brothers—slavery ended a long time ago: move on.” And, close to home: “Fuck the Upper East Side wives with their Hermès scarves and their $50 artichokes.”

The heavy- handedness that critics have objected to in some of Lee’s movies is absent from his documentaries. In Lee’s fictional films, you can sometimes feel the case of kingitis that Veronica Webb diagnosed in action: Lee just can’t seem to get enough of himself. In Bamboozled, for instance, when a character mentions Malcolm X, Lee cuts to a clip from his own film Malcolm X; later, he has another character reference his comments to the press on Quentin Tarantino (“I don’t give a goddamn what that prick Spike Lee says, Tarantino was right: Nigger is just a word”). But in his documentaries, Lee seems to strip away his ego and focus all his creative powers on the people he’s representing. His last, the Oscar- nominated 4 Little Girls, about the Birmingham church bombing of 1963, was Lee’s most critically acclaimed work to date. It was wrenching but evenhanded, understated, even.

To be fully affected by Lee’s fictional films, you have be into his vision, his aesthetic, his Spikiness. To be fully affected by his documentaries, you really just need to have eyes. The four hours of When the Levees Broke fly by. It is an astounding piece of work. The full nightmare of Katrina becomes palpable and unavoidable in a way it hasn’t yet in art. I tell Lee this, and he offers me a first and final pleasantry. A text message that says THANKS.