Jewish Montreal Painters of the Interwar Period

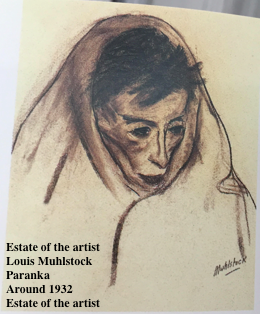

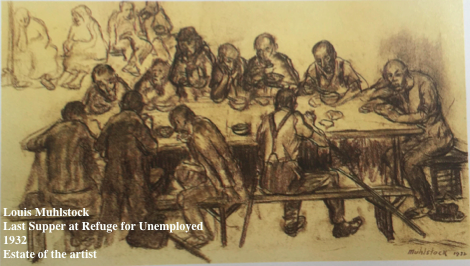

What Muhlstock Found in Empty Spaces

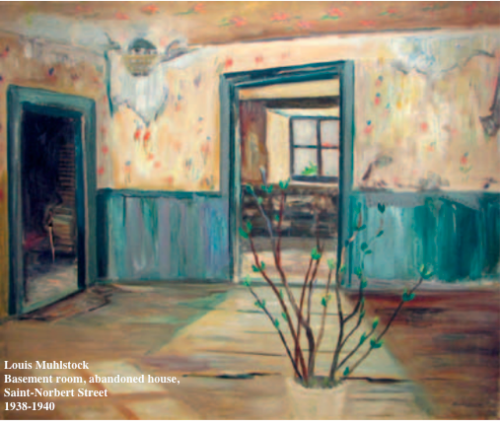

Jewish Montreal painter Louis Muhlstock (1904-2001) explored deserted apartments in the Jewish ghetto – places declared unfit for human habitation – and made them subjects of his paintings. “When I painted these empty rooms,” he said, “I painted silence and decay. I was very moved and disturbed that people were allowed to live in such surroundings and I think I expressed it through my colour. Although the people were never introduced in these paintings, there were traces of their having been here.”[1]

Basement with Tailor’s Dummy is part of a series of empty rooms captured by Muhlstock mainly during his visits in the Centre-Sud borough of Montreal. In her book Peintres juifs de Montréal Témoins de leur époque 1930-1948, Esther Trépanier notes that “these paintings appear as examples of an approach that conjugates a process of formal exploration with a particular socio-historical dimension.”[2] The female bust is reminiscent of the visual tradition of the woman subject by the window, for example in Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, all the while making a social commentary on the socio-economical situation of the Jewish community at the time.

It is a work that communicates with sensitivity the social and economical situation of the Jewish community at the time.[3] Because of low-income jobs, Jews in Montreal could often not afford to buy homes. They were not only forced to live in these slums, but were often forced out either by the intolerable living conditions or because of economic difficulties.[4] In an interview with Charles Hill from the National Gallery, Muhlstock explains the emotional magnetism between himself and the barren spaces he painted:.

“The atmosphere, we were—we lived around there, so I knew that. I didn’t know a Westmount mansion and I had no feeling for that kind. For me there was much more character in that; or I’ll show you a few things. In the door or doorway or a closed shutter or a brick wall neglected. A derelict tree that you’ll see on the wall. I had the same sort of feeling for that, and the approach was almost the same as two men sleeping in the field. It was a form. It was something I had known and experienced and seen, and so it was the thing I wanted to express.”[5]

The bust in the work most likely references the involvement of the tenants in the textile and clothing, or shmatta, industry. During and after the First World War, the rag trade was exponentially growing, producing inexpensive ready-to-wear clothing, as well as some of the worst labour conditions in the history of the country.[6] The shmatta industry employed a large number of Jewish immigrants and most of these employees lived and worked in dire conditions. By 1931, three quarter of Jews in Montreal were employed in the garment and textile industry, as manufacturers, contractors and mostly as workers.[7] The environment was thus a familiar one.

In the empty rooms series, the viewer encounters peeling wallpaper, dirty walls and desolate spaces. The rooms are immersive in pathos and emptiness, confronting the viewer to the absence of human presence all the while hinting at a faint trace of the passage of people. The social importance in this series is matched with interesting formalistic elements; the viewer is positioned as an outsider to the situation, as though peaking through a window. As for the world outside these slums, it is often reduced to a few spots of light or colour on the ground of the abandoned space. Time seems frozen, dust hangs in the air and light faintly shines through windows, cutting the space into perfect geometrical shapes.

The subjects that leave these spaces vacant are the people that Muhlstock honours in most of his oeuvre.[8] The void left by them in this series is far from neglectful; it is an homage to the people of Montreal: the workers, the beggars, the sick, the poor, the immigrants.

Blog post by Antonia Mappin-Kasirer, Research Fellow at the Museum of Jewish Montreal

Endnotes:

[1] Louis Muhlstock, interview with Monique Nadeau-Saumier recorded in his studio on St. Famille street, February 16th 1985, in Monique Nadeau-Saumier, “Sous-sol au mannequin de tailleur: un tableau témoin d’un quartier et d’une époque de Louis Muhlstock”, Journal of Canadian Art History, Vol XXXIII:1, 128.

[2] Translated from French, Esther Trépanier, Peintres juifs de Montréal: témoins de leur époque, (Éditions de l’Homme: Québec), 68.

[3] Monique Nadeau-Saumier, “Sous-sol au mannequin de tailleur: un tableau témoin d’un quartier et d’une époque de Louis Muhlstock”, Journal of Canadian Art History, Vol XXXIII:1,

[4] Terry Copp, Classe ouvrière et pauvreté : Les conditions de vie des travailleurs montréalais, (Éditions Boréales Express : Québec), 77.

[5] Louis Muhlstock, interview by Charles Hill, Canadian Painting in the Thirties, National Gallery of Canada, September 15th 1978, http://cybermuse.gallery.ca/cybermuse/servlet/imageserver?src=DO914-1000&ext=x.pdf, p. 25 .

[6] Gerald Tulchinsky, Branching Out : The Transformation of the Canadian Jewish Community, (Stoddart : North York, Ontario), 86.

[7] Alexandra Szacka, « Bases économiques et structure sociale 1931-1971 » in Anctil et Caldwell, Juifs et réalité juives au Québec, 126.

[8] See blog post Social Consciousness on the Canvas.