Unanswerable questions of the year: Is Japan really going to war? Is Japan’s peacetime constitution going to be trashed by the ruling party and returned back to the Imperial Constitution, which did not give suffrage or equal rights to women?

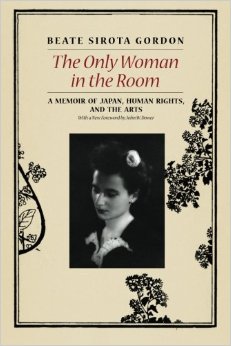

This question will be on the mind and haunt your waking hours after reading “The Only Woman in the Room” by Beate Sirota Gordon. In this memoir, she takes us through the various events in her life made remarkable by the fact that in late 1945, she became a member on the US Occupation team that drew up Japan’s National Constitution. Not only was she the only woman in the room, she was just 22 years old.

This question will be on the mind and haunt your waking hours after reading “The Only Woman in the Room” by Beate Sirota Gordon. In this memoir, she takes us through the various events in her life made remarkable by the fact that in late 1945, she became a member on the US Occupation team that drew up Japan’s National Constitution. Not only was she the only woman in the room, she was just 22 years old.

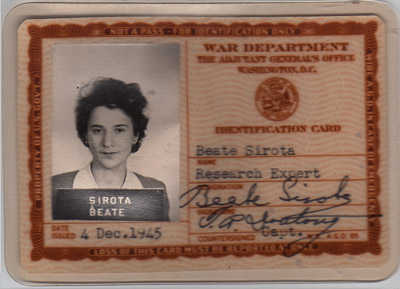

Her passport said she was an American citizen, but Beate Sirota had lived for 10 years in Akasaka, Tokyo with her Russian Jewish parents (her father Leo Sirota was a celebrated musician from Vienna and a close friend of Kosaku Yamada). For the past five years, she had been in the US while her parents had been in detention in Karuizawa. The only way to catch a plane out of America and into a ravaged, defeated Japan to see them again, was to get a job in the army. Beate’s Japan experience and the fact that she could speak, write, and read with fluency got her that position.

“The Only Woman in the Room” is honest, plain and straightforward – written not by a professional author but an extremely well-bred, cultured woman who had forged a career for herself in a time when women – even in America – were expected to marry, have babies and sink themselves in domestic bliss. Or just sink. Across the Pacific, American women her age were sizing up future husbands at cocktail parties. Beate was commuting from Kanda Kaikan to Occupation headquarters and working on the constitution 10 to 12 hours a day. She often skipped meals, since food was scarce and the work was so pressing. Her male colleagues pushed themselves harder and put in more hours – and Beate mentions that she admired and respected them for that. Her tone is never feminist, probably because she comes from a generation told to revere males and elders. Besides, she grew up in Japan where women shut their mouths and looked down when a male spoke to them, and that was exactly what she did when she first landed in Atsugi and an official asked to see her passport.

On the other hand, though her tone is consistently soft and modest, her voice is clearly her own – and when it’s time to stand up for the Japanese and their rights, she apparently didn’t give an inch. What an ally the Japanese had in Beate, especially Japanese women whom she describes in the book and in interviews she gave later on: “Japanese women are treated like chattels, bought and sold on a whim.”

Rather than change the whole world, Beate wanted to contribute to the building of a modernized Japanese society. Rather than yell out for women’s’ rights and organizing feminist rallies, she sought to raise awareness about the historical plight of Japanese women and children. And just as earnestly, she wished to help her parents, in particular her mother, who was suffering from severe malnutrition. Beate wasn’t a saint nor interested in being one. Without meaning to, she came pretty close. Her prose is never condescending, nor does it brim with self-congratulations as in the case of many memoirs. She had a story to tell and she told it and as far as she was concerned, when the story was over there was no reason for fuss or lingering.

After the army stint, Beate Sirota Gordon returned with her parents to the US in 1948, married a former colleague in the Army and later worked as the director of the Asia Society and Japan Society in New York. She continued to give interviews about her work on the Constitution but only because she felt that the peace clause (the controversial Article 9) had to be defended repeatedly. She venerated her parents and remained very close to her mother until her death, while raising a family of her own, because family and love were precious and she knew first-hand the tragedy of losing them.

What culminates from her memoirs is her selflessness. Helping others, being fair, and maintaining a striking modesty in spite of her many accomplishments were the defining factors of Beate’s life. She died in 2012 from pancreatic cancer, four months after the death of her husband Joseph Gordon. The Asahi Shimbun printed an extensive obituary on the front page, lauding her work and reminding the readers how the Constitution had protected Japan all these decades, for better or worse. Mostly for the better.

We in Japan tend to take the Constitution for granted. Many people remember and harp on the deprivation of the war years but few bother to recall the dismal details of everyday life before that. Women couldn’t go to school; they were expected to serve their parents and male siblings before marrying into households where she continued to serve and slave her husband and his clan. These women brought up their sons in the traditional way – which resulted in an unending circle of entitlement and arrogance for men, and toil and servitude for females. In poor families, parents sold off their children. Soldiers and military policemen detained ordinary citizens on the slightest suspicion and beat them during interrogation. They were responsible for committing unspeakable atrocities in China and Korea.

There was happiness, peace, equality, and respect in the Sirota household when Beate was growing up, but she knew too well how the average Japanese in Japan fared; how women and children were cut off from beauty, culture, or anything out of the familial box. She wanted a magic wand that would somehow change all that, and her idealistic, 22-year old mind told her that if she couldn’t get a wand, the Constitution was bound to be the next best thing. The task was daunting – she was working for peace and gender equality in a country steeped in tradition and ‘bushido’ feudalism. At this point in 1945, not even American women had gender equality and there she was, giving her all to ensuring that Japanese women would get that right. And just for the reason, there wasn’t nor has there ever been, anything in the American Constitution that resembles Japan’s Article 9.

At the end of the book is an elegy by Beate’s son and part of it goes like this: “Your legacy is the art of living in beauty and truth, of speaking up and out for what is right, and of finding our best selves and sharing them.”

Fabulous review. Never take the Constitution for granted. What an extraordinary moment in history for this young woman, Beate Sirota Gordon. How glad am I that she was there, not only as a witness, but more important, as a contributor to history. She gave voice to the voiceless. Knowing about her efforts makes me want to fight even harder to promote the Constitution and preserve Article 9.

Thank you. It is an amazing story.

[…] Kadın Haklarının girmesi ile ilgili bir hikayeyi burayı tıklayarak okuyabilirsiniz (ingilizce). Ben bir alıntı […]

Alone amongst our conquests,are the Japanese worthy.We are tired.We would of course,rather shatter the world than live in it as slaves.There was a time,when we were less certain of Japan’s preeminence as a success,that we supported your non aggression clause.We are tired…and all things end.Our children embrace socialism despite our warnings of it’s terrible danger.I hope to die free…but I have little hope for the millennials who seem to see freedom as a vice rather than a virtue.There may come a time when we can barely protect ourselves…we’d hate to see our greatest success fall with us when instead it could carry our torch forward.

[…] “The Only Woman in the Room”/ How The Amazing Beate Wrote Equal Rights For Women Into Japan’s Constitution 投稿日 2018 年5 月3 日 07:41:50 (japantrend) […]

Would very much like to contact the writer, Kaori Shoji, regarding this blog post about Beate.