Jews are People of the Book, but are we also People of the Sword?

I recently went with a friend to the Jewish Museum to see a small exhibit of drawings by Zoya Cherkassky, a Polish-born artist who emigrated to Israel in 1991. These drawings were done within days of the Hamas incursion into Israel on October 7th, when terrorists killed more than 1,200 people, took over 240 hostages (including about one dozen Americans), and wounded many people from various countries. The artist is on the left of Israel’s political spectrum; earlier this year she responded to violence committed by Israeli settlers with a drawing of a Palestinian family with their house in flames.

The drawings are rendered in bright colors against black backgrounds, depicting uniformly violent scenes of kidnapping, rape, and killing (there is a trigger warning at the start of the exhibit) and are the more chilling in their graphicness. Although one can see traces of earlier artists, including Pablo Picasso, Kathe Kollwitz and Edvard Munch, the images are very much Cherkassky’s own — flattened out and childlike, suggesting an immediacy born of horror. It is impossible to look at them and not be reminded of the almost surreal quality of the attack, which itself seemed like a murderous form of child’s play.

In the cab going to the museum, I drew in my breath when my friend gave the address; later I told him that I would have just said “93rd and Fifth” without spelling out our exact destination. The truth is, I was afraid, for the first time in my life, as being marked out as Jewish. This might seem paranoid: what, precisely, was I afraid of? That the cab driver might turn around and express his hostility– or, worse yet, take out a pistol and shoot us? It is easy to scoff or express disbelief at my fear, given that this was New York City, and that I was a citizen of a pluralist democracy. And yet: the very next day a dinky Jewish Cafe on the Upper West Side called Effy’s was sprayed with red paint and anti-Semitic graffiti.

My fear has been a while in coming – six months, to be exact, ever since, within ten days of the Hamas onslaught, the quintessential Jewish 2nd Avenue Deli, was defaced by a swastika chalked or sprayed on its storefront. The restaurant, with its cozy, diner decor, had always been a place of refuge for me, offering the Jewish (and kosher) equivalent of comfort food – chicken soup, gefilte fish and chopped liver.

The swastika put a chill through me, as a reminder of a monstrous past and a potential foreshadowing of monstrosities to come. At around the same time, the message “Kill the Jews” was scrawled with a black marker, next to what appears to be a misshapen swastika, on a subway wall at Herald Square. This feeling of fear has, undoubtedly, also to do with what is going on in Israel, specifically what appears to be one-sided ferocity of the Gazan war (the enemy is often invisible, hidden among everyday Palestinian people, and the effort to extirpate them is likely quite difficult), not to mention Israel’s disdain for optics and the media’s corresponding disdain for them.

I am an unshakable Zionist, but also one who, especially given the values of our religion, has questions about the protracted human cost of Israel’s military response (call it realpolitik, if you like), led by Netanyahu, Israel’s own version of Trump. But the fact that I see the response as problematic, coming from a people who know better than anyone what it is to be hounded and persecuted, makes no difference. Global anti-Semitism conflates all Jews – Israeli, American, European – into one despised Jew. There is no room, that is, for distinctions or subtleties. And now we have hatred on both flanks: I fear the Right, who’ve long thought we have horns and eat babies, no matter that they back Israel for their own transactional reasons. From the Left, what people suggest is that Jews are killing women and children, without any end in sight. Still, whatever one thinks of Israel’s response to the brutal and bloody attack, we need to acknowledge that it is fueled by a sense of radical threat and a reawakened sense of trauma at being vulnerable to the destructive fortitudes of an enemy who is intent on wiping it out of existence.

As I’ve been discussing the growing feeling of fear with my Jewish friends, I’ve wondered why none of us are reacting with rage alongside our fear. Rage, one would think, is a natural response to aggression — and yet, with all the animus and violence that has been hurled at Jews over the centuries, has anyone ever been confronted, at least out here in the diaspora, with an outbreak of Jewish rage?

Jews have long been sensitized to the historical undertow of an implacable antisemitism that subsides only to re-emerge at pivotal flashpoints, whether it be eruptions in the Mideast or the latest kerfuffle in academia, which often trades in anti-Zionist rhetoric in the service of teaching the evils of structural inequity. As the daughter of German Jewish parents who had to escape Germany in the 30’s because of the rise of Nazism, I feel especially threatened by such incidents. In the study where I write this, I can look up at a framed photograph taken in 1938 by the German photographer Edmund Engelmann shortly before Sigmund Freud fled Vienna, of a cloth banner with a swastika insignia hung above the double doors of Freud’s apartment building, right next to Kornmehl, a kosher butcher.

The truth is that Jewish rage has, for the most part, been confined to the literary and theoretical; Jewish liturgy contains several examples of Jewish bloodthirstiness, such as a short but intense prayer at the Passover seder and the memorial prayer Av HaRachamim, which is recited at various times during the week and asks God to redress the deaths of Jews and seek vengeance on our enemies. Although Jews have been historically uncomfortable with spilling blood, they have also been capable of active resistance, as was shown by the intrepid partisans during the Second World War. Not to overlook the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which, doomed as it was, manifested a determination on the part of ghetto residents not to be gunned down by the Nazis like the sheep Jews have often been accused of being.

All the same, during the 1936-1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, the official Jewish position of the yishuv (a national liberation movement established in the 1920’s made up of the Jews then living in Palestine) was havlaga, which means “the restraint.” And even Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the fierce founder of the Jewish revisionist movement in Palestine in 1925, which included paramilitary training camps for Jewish youth, believed that “it is one of our racial weaknesses (too often taken advantage of) that with us resentment does not necessarily imply the desire for revenge.” Tragically, this kind of reflection and the embrace of anything like restraint are absent from the absolutist vision of Netanyahu and his lieutenants.

In general, however, diaspora Jews have not wanted to make waves about the continuing scourge of antisemitism, on whatever level it presents itself. When discriminatory racial quotas on Jewish admissions to various prestigious universities in America were instituted in the late 19th and 20th centuries — in 1922 the Admissions chairman of Yale urged limits, characterizing Eastern European Jews as “the alien and unwashed element” — Jewish students just studied even harder, and eventually, in 1948, Brandeis University was founded, sponsored by the Jewish community.

But this was a kinder, gentler anti-Semitism. What happens when the antisemitism is of a more pernicious sort, such that it leads to swastikas being emblazoned on delis and bomb threats to Jewish schools and synagogues? Is there still no cause for Jewish rage, then?

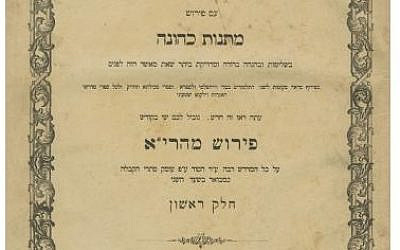

“The sword and the book came down intertwined from heaven”, says the Medrash Devarim Rabbah, 4:2, and the Jews became a people of the book and not a people of the sword. We were raised to be thoughtful and law-abiding citizens who value life, and no Gaza invasion or narratives of marauding West Bank settlers, however tragic the consequences, signal a change in our basic temperament. It is only in a land that we call our own, Israel, that the ethos of the sword – an eye for an eye —has been robustly claimed, to the consternation of the watching world, who are often more favorable to the Jew as victim rather than the Jew who fights back.

Perhaps Jewish rage, as befits so cerebral a people, comes down to no more than agitating by means of protest in print and public forums. In America there is no clear enemy but rather a structural form of antisemitism, every bit as ingrained as anti-black racism. It is, however, more nuanced and implicit. That is: we pass, but we don’t pass. Growing up on the Upper East Side as a member of a modern Orthodox Jewish family, I remember the effort that was put into not appearing “too” Jewish: My brothers wore Eton caps instead of yarmulkes when they went outside and when I wore sneakers on Yom Kippur, in keeping with the prohibition against wearing leather, I felt as I walked to synagogue along Park Avenue that I might as well have been wearing a yellow star. Although this country had offered Jewish people a warm welcome, it seems to me that we remain, deep down, tentative about our belonging and disinclined to call too much attention to any offence against us. We are more likely, that is, to paint over the swastika on the deli than to paint furious graffiti ourselves.

Jewish rage may come down to no more than agitating by means of protest in print and public forums – or, as was recently done by several Jewish benefactors and philanthropists, withdrawing funding from institutions which come out against the Jewish right to defend themselves in their own land. But I find myself uninspired by these responses; they seem paltry in the face of an increasingly grim reality. On the other hand, the Israeli military strategy, which is to bombard violently, to inspire fear through killing, seems too morally incongruous, too un-Jewish, too far from our bookish tradition where bellicose arguments got – and still get — settled by pious rebbes at the bet-din, the Jewish court of law.

Jean-Paul Sartre, in his essay “Anti-Semite and Jew” (originally titled in French “Reflections on the Jewish Question)”, published in 1946, posited that antisemitism was not merely a way of thinking but a passion. Passions are not only impervious to logic but have an unshakable grip on those they beset. Still, if what Sartre argues is true, and I believe it is, it is high time that we stare antisemitism down with a steely and vigilant passion of our own, one that is based not on a call to arms but to alarm and intense political action. To do otherwise is to live in a delusion.